INTRODUCTION

Tissue expansion is the technique that allows the reconstruction of defects by

the gradual distension of a flexible skin area, preparing it for use in solving

any defect such as breast reconstruction, burns, and giant nevi1. This reconstructive method has advantages

such as the use of tissues of color and texture similar to the defect, less

damage to the donor area, and aesthetic improvement.

In burns, tissue expansion is indicated when the wounds have completely healed,

and the resulting scars need to be treated. Patients with burn sequelae may have

limited tissue availability for flaps. Specific areas such as the scalp benefit

from tissue expansion by allowing the treatment of sequelae with similar

tissue2 (Figure 1), as well as the head and neck region. The expansion can be

done in tissues surrounding the wound, or donor areas of free flaps in

situations that nearby regions are not available3.

Figure 1 - Patient with an area of alopecia on the scalp due to the burn

submitted to treatment with tissue expander. A.

Preoperative period; B. Final result after three-stage

treatment with round type expanders.

Figure 1 - Patient with an area of alopecia on the scalp due to the burn

submitted to treatment with tissue expander. A.

Preoperative period; B. Final result after three-stage

treatment with round type expanders.

Giant congenital nevus can be defined as an ectopic concentration of melanocytes

of neuroectodermal origin with a diameter greater than 20 cm and affecting about

1 in every 20,000 live births4. Besides

the aesthetic implications, patients with this type of anomaly need to deal with

5 to 12% associated risk of malignancy. Therefore, prophylactic excision is

recommended4. The use of tissue

expanders is frequent in this treatments5.

The number of procedures involving skin expanders for breast reconstruction has

also been increasing. Statistics from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons,

in 20166, show that approximately 90% of

breast reconstructions with prostheses are performed in two stages, the first

of

which is tissue expansion (Figure 2). The

use of expanders may also be required in breast agenesis. In Poland’s syndrome,

there is a partial or total absence of the pectoralis major, pectoralis minor,

serratus and breast muscles, and the nipple-areola complex; therefore, expansion

is one of the techniques used in its treatment7

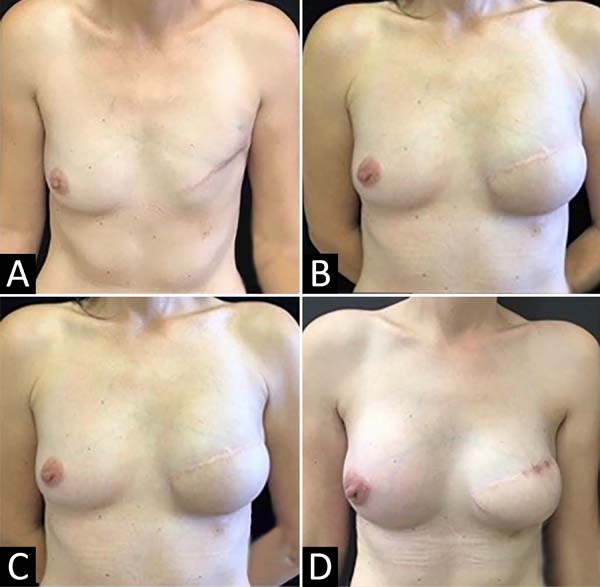

Figure 2 - Patient undergoing treatment for left breast for ductal carcinoma

in situ. Late breast reconstruction was performed with a large

dorsal flap and a round, smooth expander with a remote valve. After

six months, and after the expansion was completed, she was replaced

with an expander for prosthesis and symmetrization with a zigzag

periareolar augmentation mammoplasty. A. Preoperative

period; B. Result after placing the expander;

C. Result after replacing the expander with the

prosthesis; D. Final result.

Figure 2 - Patient undergoing treatment for left breast for ductal carcinoma

in situ. Late breast reconstruction was performed with a large

dorsal flap and a round, smooth expander with a remote valve. After

six months, and after the expansion was completed, she was replaced

with an expander for prosthesis and symmetrization with a zigzag

periareolar augmentation mammoplasty. A. Preoperative

period; B. Result after placing the expander;

C. Result after replacing the expander with the

prosthesis; D. Final result.

OBJECTIVE

This article has as main objective to report the experience of the plastic

surgery service at the Hospital de Clínicas of the Federal University of Paraná

(UFPR) with the use of expanders, emphasizing the complications found, their

possible causes and management.

METHODS

This is a retrospective, descriptive, and analytical study of patients who

underwent tissue expansion for reconstructive surgery at Hospital de Clínicas

da

UFPR. This study was submitted and approved by the Ethics and Research Committee

of the Hospital de Clínicas da UFPR (approval number: 68550217.4.0000.0096).

Medical records of patients who underwent expansion between January 2010 and

December 2016 were analyzed. All patients who underwent surgery for tissue

expansion during this period were included. Exclusion criteria included the

abandonment of treatment and the death of the patient during this period. The

data obtained were age, gender, pathology indicative of the procedure, type of

expander, insertion site, evolution, and complications.

From the data obtained, a descriptive statistical analysis was carried out,

emphasizing the relationship between the complications found and parameters,

such as the cause of treatment, the format of the expander, and the insertion

site.

RESULTS

Sixty-one patients and 80 surgeries, including reexpansion procedures, were

analyzed. The majority of patients were female (83.6%). The age at the first

surgical stage of the patients analyzed was between 2 and 73 years (mean 31),

with the majority in the age group above 40 years (41%), followed by young

people between 11 and 20 years (27.9%). The main indication for surgery was

breast reconstruction after mastectomy (36%), followed by a burn scar correction

(31.1%) and giant nevi correction (14.7%). Other causes include post-trauma scar

correction (6.6%), vascular malformation correction (4.9%), breast agenesis due

to Poland’s syndrome (3.3%), microtia (1.6%), and resection of dermofibrosarcoma

(1.6%).

Concerning the complications most seen in the procedures performed, signs of

infection (14.7%) stand out. Other complications observed were: suture

dehiscence (3.2%), seroma (3.2%), expander defect (3.2%), expander exposure

(3.2%), necrosis (1.6%) and signs of hypoperfusion (1.6%).

Patients undergoing breast reconstruction had the highest number of

complications. Considering the 22 patients who received treatment, four

presented, in the first stage, infectious signs in the breast where the expander

was placed, and another four presented the following complications each:

exposure of the expander, dehiscence of the suture, seroma and signs of

hypoperfusion. In five cases, it was necessary to remove the expander. Patients

suffering from seroma, and exposure only needed to relocate the expanders. One

of the patients died due to cancer complications.

Among patients undergoing expansion to correct burns, two showed signs of

infection after surgery. Two others presented complications due to suture

dehiscence and one due to defect in the expander. They all required the removal

of the expander. Forty percent of the complications in patients with burn

sequelae were in the lower limbs. The other correlations between the cause of

treatment and the percentage of complications are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 - Indications for expansion surgery and number of complications *.

| Etiology |

Number of patients |

% Total |

Number of complications |

% Complications |

| Breast reconstruction |

22 |

36 |

9 |

40.1 |

| Burn sequel |

19 |

31.1 |

5 |

26.3 |

| Giant Nevus |

9 |

14.7 |

3 |

33.3 |

| Post-trauma scar sequel |

4 |

6.6 |

1 |

25.0 |

| Vascular malformation |

3 |

4.9 |

1 |

33.3 |

| Poland syndrome |

2 |

3.3 |

1 |

50.0 |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma resection |

1 |

1.6 |

1 |

100.0 |

| Microtia |

1 |

1.6 |

0 |

0 |

Table 1 - Indications for expansion surgery and number of complications *.

The chest region was associated with a higher number of complications than other

parts of the body: 11 of the 28 patients who underwent the procedure in this

region had some type of complication. The other correlations between the

anatomical region submitted to expansion and complications are shown in Table 2.

Table 2 - Anatomical region submitted to expansion and number of complications

*.

| Anatomical region |

Number of patients |

% Total number of patients |

Number of complications |

% |

| Complications |

|

|

|

|

| Chest |

28 |

45.9 |

11 |

39.3 |

| Lower limbs |

9 |

14.8 |

3 |

33.3 |

| Scalp |

9 |

14.8 |

2 |

22.2 |

| Face |

8 |

13.1 |

2 |

25.0 |

| Back |

7 |

11.5 |

1 |

14.3 |

| Abdomen |

2 |

3.3 |

0 |

0 |

| Upper limbs |

1 |

1.6 |

0 |

0 |

| Neck |

1 |

1.6 |

1 |

100.0 |

Table 2 - Anatomical region submitted to expansion and number of complications

*.

Regarding age, the greatest number of complications occurred in patients over 40

years of age. In this group, 36% had some type of complication (Table 3).

Table 3 - Distribution of patients by age and number of complications.

| Age (years) |

Number of patients |

% Total |

Number of complications |

% of Complications |

| 0-10 |

9 |

14.8 |

3 |

33.3 |

| 11-20 |

17 |

27.9 |

5 |

29.4 |

| 21-30 |

6 |

9.8 |

0 |

0 |

| 31-40 |

4 |

6.6 |

1 |

25.0 |

| >40 |

25 |

41.0 |

9 |

36.0 |

Table 3 - Distribution of patients by age and number of complications.

Reexpansion was necessary for 37.7% of patients. Of the 19 surgeries performed on

these patients for reexpansion, two had complications. One of the patients who

underwent breast reconstruction showed signs of infection, while the second

surgery of a patient with a giant nevus had the expander’s exposure.

The majority of patients started the expansion during the intraoperative period

(95%), and the time of evolution varied from 0 to 168 months, with an average

of

58.9 months.

Table 4 shows the number of complications

concerning the year.

Table 4 - Distribution of cases concerning the year and the number of

complications *.

| Year of surgery |

Number of surgeries |

Number of complications |

% of complications |

| 2010 |

8 |

3 |

37.5 |

| 2011 |

11 |

2 |

18.2 |

| 2012 |

17 |

4 |

17.6 |

| 2013 |

17 |

4 |

23.5 |

| 2014 |

14 |

3 |

21.4 |

| 2015 |

7 |

2 |

28.6 |

| 2016 |

6 |

3 |

33.3 |

| Total |

80 |

21 |

|

Table 4 - Distribution of cases concerning the year and the number of

complications *.

DISCUSSION

In the mid-1950s, Neumann was the first surgeon to use an expander implant

through a latex balloon to enlarge the periauricular region after an ear

trauma8. Since then, skin expanders

have been used for the most diverse procedures.

In terms of shape, an expander follows three patterns: round, rectangular, and

semi-lunar (croissant). The rectangular is known for allowing additional tissue

expansion, thus increasing the options for flap design. The valve can be

integrated into the expander or attached via a silicone tube.

The content of the expanders available on the market is almost always a saline

solution. Another option found is filling with carbon dioxide, recently approved

by the “US - Food and Drug Administration (FDA)” 9.

In the Plastic Surgery Service of Hospital de Clínicas da UFPR, the three types

of expanders are used, the round one being recommended in breast reconstructions

and the croissant and rectangular types most used in other types of surgery,

such as treating burn sequelae, for example. The contents of these expanders

have always been a saline solution.

A critical point to be defined in the preoperative period is the expansion

design. Attention should be paid to the donor site as infections, trauma, and

unstable scarring can lead to implant failure or extrusion. The incision site

must also be chosen with caution. For example, if the goal is to remove an

injury, it is appropriate to position the incision at the edges of the

injury.

The majority of expansions begin during the intraoperative period, when a volume

is placed making a slight compression to avoid the hematoma formation, since

in

most cases - except for breast reconstruction - a vacuum suction drain is not

used. Although there are many citations in the literature to start the expansion

in one to three weeks after the expander is inserted, in our service, the scar

is expected to mature more, and tissue expansion begins in about four weeks.

If

there are no complications, weekly expansion is performed, until the required

volume is reached. The use of state-of-the-art or osmotic expanders with

self-inflating expansion may eliminate the need for repeated injections,

reducing the number of infections and other complications10. However, there are still no such devices commercially

available in our market11.

The profile of patients, the number of surgeries, and the number of complications

have changed in our department in recent decades if we compare it with a study

by Freitas et al., from 2011. In the period from January 2005 to December 2009,

most of these patients were in their second decade of life and underwent

expansion due to burning sequelae. In the present study, we found a prevalence

of women over the fourth decade of life undergoing breast reconstruction

treatment after radical mastectomy, with the old profile of patients in the

second position. This change in profile is consistent with the worldwide

increase in the number of breast reconstruction procedures with prostheses

performed in two stages, the first of which is tissue expansion6. In proportion to the number of surgeries

performed in the last decades12, the

number of complications has decreased.

In patients undergoing radical mastectomy for cancer treatment, a significant

challenge is a need for post-surgical radiation. Radiation leads to fibrosis,

which compromises the quality of the skin and subcutaneous tissue, resulting

in

higher incidences of complications and possibly impairing the final aesthetic

result13. These complications may

conduct to the need of the radiotherapy treatment interruption, thus

compromising the final result. In other situations, it may be necessary to

deflate the expander to allow adequate access to the chest wall and internal

mammary lymph nodes.

In burns, the most common complications are infection, exposure, and expander

malfunction. According to Bozkurt et al., N 200814, the highest number of complications in these patients occurs in

the head region, and when using larger expansion volumes (400 and 800ml).

However, the results obtained in this research are in line with LoGiudice and

Gosain (2003)15, with more significant

complications in the lower limbs, possibly due to less rich vascularization and

the amount of tissue available region.

The highest incidence of complications with the age group is found in patients

over 40 years old and those between 11 to 20 years old, coinciding with the age

groups with the highest prevalence in patients after radical mastectomy and burn

sequelae.

It is essential to know the types of complications, frequency, and associated

factors to minimize them. Besides, the choice of the best expander option and

the correct surgery technique and expansion are essential for a good result.

The

future of the skin expansion technique is auspicious. The increase in the number

of studies observed in the last decades on expansion, not only of skin but also

of nerves, bones, and other parts of the body, can be of great value to surgeons

in the future16.

CONCLUSION

The skin expansion technique is indicated for several pathologies’ treatment.

Besides, the patient profile treated at the Hospital de Clínicas da UFPR has

changed in the last decades. Since 2010, there has been an increase in the

number of patients who underwent treatment for breast reconstruction, exceeding

the number of patients due to burning sequelae who underwent the same procedure.

Most of the complications observed in these patients were infections related

to

the insertion of expanders in the chest region to perform the breast

reconstruction procedure.

REFERENCES

1. Di Mascio D, Castagnetti F, Mazzeo F, Caleffi E, Dominici C.

Overexpansion technique in burn scar management. Burns. 2006

Jun;32(4):490-8.

2. Tavares Filho JM, Belerique M, Franco D, Porchat CA, Franco T.

Tissue expansion in burn sequelae repair. Burns. 2007

Abr;33(2):246-51.

3. Barret JP. ABC of burns: burns reconstruction. BMJ.

2004;329(7460):274-6.

4. Paschoal FM. Nevo melanocítico congênito. An Bras Dermatol. 2002

Nov/Dez;77(6):649-58.

5. Viana ACL, Gontijo B, Bittencourt FV. Giant congenital

melanocytic nevus. An Bras Dermatol. 2013 Nov/Dez;88(6):863-78.

6. American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS). Plastic surgery

statistics [Internet]. Arlington Heights, IL: ASPS; 2016; [acesso em 2017 Abr

01]. Disponível em:

https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plastic-surgery-statistics?sub=2016+Plastic+Surgery+Statistics

7. Araujo MP, Araujo AJ. Sindrome de Moebiüs-Poland: relato de caso.

Rev Med. 1999;78(3):371-7.

8. Ashley KL, Bruce SB. Tissue expansion. In: Thorne CH, ed. Grabb

and Smith’s Plastic Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Wilians Wilkins; 2013.

p. 512-40.

9. Ascherman JA, Zeidler K, Morrison KA, Appel JZ, Berkowitz RL,

Castle J, et al. Carbon dioxide-based versus saline tissue expansion for breast

reconstruction: results of the XPAND prospective, randomized clinical trial.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016 Dez;138(6):1161-70.

10. Chummun S, Addison P, Stewart KJ. The osmotic tissue expander: a

5-year experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010

Dez;63(12):2128-32.

11. Pitanguy I, Radwanski HN, Amorim NFG, Lintz JE, Moraes Neto AEM.

The use of tissue expanders in burn sequelae. Acta Med Misericordia.

2000;2(3):59-64.

12. Freitas RS, Oliveira e Cruz GA, Scomação I, Nasser IJG, Colpo

PG. Tissue expansion at Hospital de Clínicas-UFPR: our experience. Rev Bras Cir

Plást. 2011 Set;26(3):407-10.

13. Nano MT, Gill PG, Kollias J, Bochner MA, Malycha P, Winefield

HR. Psychological impact and cosmetic outcome of surgical breast cancer

strategies. ANZ J Surg. 2005 Nov;75(11):940-7.

14. Bozkurt A, Groger A, O’Dey D, Vogeler F, Piatkowski A, Fuchs

PCH, et al. Retrospective analysis of tissue expansion in reconstructive burn

surgery: evaluation of complication rates. Burns.

2008;34(8):1113-8.

15. LoGiudice J, Gosain AK. Pediatric tissue expansion: indications

and complications. J Craniofac Surg. 2003 Nov;14(6):866-72.

16. Wood RJ, Adson MH, Van Breek AL, Peltier GL, Zubkoff MM, Bubrick

MP. Controlled expansion of peripheral nerves: comparison of nerve grafting and

nerve expansion/repair for canine sciatic nerve defects. J Trauma. 1991

Mai;31(5):686-90.

1. Hospital de Clínicas, Federal University

of Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Kethelyn Keroline Telinski Rodrigues

Avenida Presidente Getúlio Vargas ,1811, Apart. 41 , Rebouças, Curitiba, PR,

Brazil. Zip Code: 80240-040, E-mail:

kety.rodrigues@gmail.com

Article received: March 03, 2020.

Article accepted: July 15, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none.