INTRODUCTION

Aging will inevitably reshape the world as we know it. This is a gradual process,

leading to changes with an impact on health, well-being, social class, and

individual usefulness in society. The current challenge is to understand the

changes that already directly affect quality of life (QOL)1.

QOL is a multidimensional construct, and each of its aspects (physical,

emotional, psychological, spiritual, and social) is important to an individual,

especially in old age, which is a heterogeneous stage of life2.

Several studies have shown that cosmetic surgery (CS) can improve the physical

and mental aspects of QOL2,5, especially

with respect to self-esteem, regardless of age, sex, or race.

Self-esteem is an important measure of mental health, defined as a sense of value

and acceptance of oneself. The elderly tend to lose self-esteem due to changes

in appearance and function, personal loss, and loss of employment. Such

difficulties expose the elderly to anxiety and depression. Thus, actions that

favor an increase in self-esteem are important to mental health6.

Improvement of self-esteem has been identified as the main motivation to undergo

CS. For the elderly, CS, along with less invasive esthetic procedures, can

mitigate the most visible aspects of aging, thus improving self-esteem7.

Despite demonstrable improvement in self-esteem and QOL, rates of CS are still

low among the elderly. Data from the American Society of Plastic Surgery show

that 23% of 373,418 CS cases performed in 2015 were in those over 55 years of

age; there was no specific survey of patients over 65 years of age, which is

considered elderly in developed countries8. In Brazil, 5.4% of all plastic surgeries are performed in those aged

65 years or older9.

OBJECTIVE

Given the heterogeneity of aging and the perception of this phase of life, it is

important to study the changes caused by cosmetic procedures in the elderly. The

need to assess the association between CS and QOL in the elderly and its effects

on self-esteem prompted a comparative study among elderly patients who did or

did not undergo CS.

METHODS

This was a descriptive, case-control study, matched for socioeconomic conditions;

only female participants were chosen because they represent a majority (84.6%)

of CS cases worldwide. The sample consisted of 2 groups of women aged 60 years

and above, 25 of whom underwent CS (case group) in the prior 5 years at a

private plastic surgery practice near Brasília. These were matched with 25

elderly members of the Center for the Coexistence of the Elderly (CCI),

maintained by the Universidade Católica de Brasília (UCB). This control group

did not undergo CS. The 2 groups were matched according to age, marital status,

education, and region of residence.

The case group included women aged 60 years or older who underwent CS between

2013 and 2017; the control group included elderly women who did not undergo CS.

The exclusion criteria for both groups were: prior reconstructive plastic

surgery, dementia, visual and auditory loss, inability to communicate, or

residence other than in Taguatinga.

After informed consent was provided, an individual interview was held, with the

researcher completing the questionnaires to avoid fatigue or other possible

limitations in the elderly subjects10.

The Mini-Mental State Examination11, a

cognitive, functional, and behavioral assessment instrument, was then applied to

evaluate cognitive status, using the following cut-offs: for those without

formal education, 20 points; for those with primary or secondary education, 25

points; and for those tertiary education, 28 points12.

Those considered appropriate based on cognitive assessment then completed a

questionnaire developed specifically for this study, to determine socioeconomic

parameters, medical history, surgical history, motivation, and impact of CS on

personal life and relationships. The control group was asked whether or not CS

had been considered. Depending on the answer, the motivations for or against CS

were evaluated.

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale13 includes

5 items relating to a positive self-image and 5 related to a negative

self-image; values and attitudes were assessed using a Likert scale14.

The interview ended with completion of the World Health Organization Quality of

Life-Bref (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire15,

which evaluates the physical, psychological, social, and environmental domains

for each subject. The WHOQOL-BREF was chosen because it surveyed satisfaction

with physical appearance and presented a smaller number of questions (26, with 5

response options).

The data were analyzed using STATA software, version 14.0. We performed the

Shapiro-Wilk test to assess normality of quantitative variables, followed by a

descriptive analysis. Qualitative variables were expressed as absolute and

relative frequency and quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation.

The Mann–Whitney U test, Fisher’s exact test, and Cronbach’s alpha for

reliability were also used.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade

Católica de Brasília (No. 2124672, protocol CAAE 69067917.5.0000.0029).

RESULTS

Of 50 elderly women in the present study, 25 were in group 1 (non-operated or

control group) and 25 in group 2 (operated or case group). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the

sample.

Table 1 - Sociodemographic characteristics.

| Variables |

Total (n = 50) |

Group 1 |

Group 2 |

p-value

|

| |

(n = 25) |

(n = 25) |

(n = 25) |

|

| Age (years), mean+ SD |

67.26+5.35 |

67.36+5.49 |

67.16+5.32 |

0.9151 |

| Education (years), mean+ SD |

9.96+4.84 |

9.44+4.77 |

10.48+4.95 |

0.3951 |

| Income (minimum), mean+ SD |

4.58+3.36 |

3.00+2.08 |

6.16+3.68 |

0.0011 |

| Marital status, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| With partner |

16 (32.0) |

7 (28.0) |

9 (36.0) |

0.7622 |

| Without partner |

34 (68.0) |

18 (72.0) |

16 (64.0) |

|

| Ethnicity, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| White |

17 (34.0) |

8 (32.0) |

9 (36.0) |

0.0332 |

| Black |

6 (12.0) |

6 (24.0) |

- |

|

| Mixed |

16 (27.0) |

11 (44.0) |

16 (64.0) |

|

| Educational level, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| Primary |

20 (40.0) |

11 (44.0) |

9 (36.0) |

0.7692 |

| Secondary |

15 (30.0) |

8 (32.0) |

7 (28.0) |

|

| Tertiary |

15 (30.0) |

6 (24.0) |

9 (36.0) |

|

Table 1 - Sociodemographic characteristics.

Most of the elderly subjects were non-smokers, did not consume alcohol, and had

comorbidities, especially hypertension and dyslipidemia.

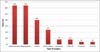

The average number of surgeries per patient was 2.16 (SD = 1.21), with a minimum

of 1 surgery and a maximum of 5; 36% had 1 CS and 64% had more than 1 CS,

concomitantly or at different times. The most common surgeries were

abdominoplasty and blepharoplasty, with 64% undergoing both, followed by

facelift or rhytidectomy (40%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Types of surgeries performed in the case group.

Figure 1 - Types of surgeries performed in the case group.

Of the 25 women in the case group, 16.0% had postoperative complications.

The complications included dehiscence (12%), seroma (8%), hematoma (4%), TEP

(4%), and infection (4%). Six patients (24%) underwent surgical revision to

improve the cosmetic result, most frequently for unsightly scars.

When asked about the motivation for surgery, physical discomfort, improvement of

QOL, and dissatisfaction with self-image were the reasons most often cited,

followed by the desire for rejuvenation and improvement of social interactions

(Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Motivation for surgery.

Figure 2 - Motivation for surgery.

The level of satisfaction is shown in Table 2.

Table 2 - Level of satisfaction among elderly women who underwent

surgery.

| Aspect |

Level of satisfaction |

| Very little |

Little |

Fair |

High |

Very high |

| With life |

- |

- |

2 (8.0) |

14 (56.0) |

9 (36.0) |

| Self-image |

1 (4.0) |

1 (4.0) |

2 (8.0) |

12 (48.0) |

9 (36.0) |

| Relationship with partner |

14 (56.0) |

3 (12.0) |

3 (12.0) |

4 (16.0) |

1 (4.0) |

| Relationship with family |

8 (32.0) |

3 (12.0) |

4 (16.0) |

8 (32.0) |

2 (8.0) |

| Work |

17 (68.0) |

2 (8.0) |

- |

4 (16.0) |

2 (8.0) |

| Social |

5 (20.0) |

3 (12.0) |

1 (4.0) |

13 (52.0) |

3 (12.0) |

Table 2 - Level of satisfaction among elderly women who underwent

surgery.

Table 3 shows the mean scores for the

items and the overall scores on the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale, as well as the

reliability of the instrument in each group. The Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale in

both groups showed a standardized Cronbach’s alpha of 0.715, suggesting good

internal reliability in the sample. Similar values were found for the case and

control groups. There was no statistical difference in the overall self-esteem

score between the case and control groups. However, the case group had a higher

self-esteem score related to items 4 and 8 (improved sense of capability and

self-respect).

Table 3 - Comparison between items and self-esteem scores on the Rosenberg

Scale in both groups

| Items |

Total group (n = 50) |

Group 1 (n = 25) |

Group 2 (n = 25) |

p-valor1 |

| 1 |

3.10 ± 0.42 |

3.00 ± 0.29 |

3.20 ± 0.50 |

0.081 |

| 2 |

3.10 ± 0.36 |

3.00 ± 0.29 |

3.20 ± 0.41 |

0.053 |

| 3 |

3.31 ± 0.62 |

3.24 ± 0.66 |

3.40 ± 0.57 |

0.408 |

| 4 |

3.04 ± 0.49 |

2.88 ± 0.33 |

3.20 ± 0.58 |

0.020 |

| 5 |

3.16 ± 0.51 |

3.04 ± 0.35 |

2.38 ± 0.61 |

0.073 |

| 6 |

3.12 ± 0.38 |

3.04 ± 0.35 |

3.20 ± 0.41 |

0.147 |

| 7 |

3.04 ± 0.57 |

3.08 ± 0.49 |

3.00 ± 0.64 |

0.637 |

| 8 |

2.78 ± 0.54 |

2.60 ± 0.50 |

2.96 ± 0.54 |

0.023 |

| 9 |

4.96 ± 0.73 |

3.04 ± 0.79 |

2.88 ± 0.67 |

0.450 |

| 10 |

3.60 ± 0.67 |

3.76 ± 0.52 |

3.44 ± 0.77 |

0.075 |

| Global |

31.22 ± 2.82 |

30.68 ± 2.62 |

31.76 ± 2.96 |

0.341 |

| Reliability |

|

|

|

|

| Cronbach alpha |

0.715 |

0.724 |

0.709 |

- |

| CCI (95% CI) |

0.701 (0.560-0.811) |

0.732 (0.542-0.864) |

0.685 (0.462-0.841) |

- |

| p-value

|

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

- |

Table 3 - Comparison between items and self-esteem scores on the Rosenberg

Scale in both groups

None of the subjects were found to have low self-esteem. The prevalence of high

self-esteem was greater in the case group than in the control group (68% vs.

52%), although this difference was not statistically significant

(p = 0.387).

A positive correlation was observed between low self-esteem and age

(rs = 0.312; p = 0.027), i.e., the greater the

age, the greater the self-esteem.

No significant difference was observed in the QOL scores for physical,

psychological, social, and global relationships (p > 0.05).

However, the QOL scores for the environmental domain (p =

0.002) were significantly higher in the case group than in the control group. In

the descriptive analysis, the mean WHOQOL-BREF scores were higher in the case

group for questions 24 and 25 (health services and means of transport) than in

the control group (Table 4).

Table 4 - Comparison of the WHOQOL-BREF items between groups.

| Question |

Total group (n = 50) |

Group 1 (n = 25) |

Group 2 (n = 25) |

p-Value1 |

| 1 |

3.94 ± 0.68 |

3.92 ± 0.64 |

3.96 ± 0.73 |

0.707 |

| 2 |

3.66 ± 0.74 |

3.68 ± 0.55 |

3.64 ± 0.91 |

0.923 |

| 3 |

2.04 ± 1.16 |

2.08 ± 1.19 |

2.00 ± 1.15 |

0.740 |

| 4 |

3.34 ± 0.92 |

2.40 ± 0.96 |

2.28 ± 0.89 |

0.573 |

| 5 |

3.20 ± 0.86 |

3.28 ± 0.94 |

3.12 ± 0.78 |

0.316 |

| 6 |

3.82 ± 0.56 |

3.76 ± 0.44 |

3.88 ± 0.67 |

0.349 |

| 7 |

3.16 ± 0.68 |

3.24 ± 0.66 |

3.08 ± 0.70 |

0.416 |

| 8 |

3.79 ± 0.58 |

3.84 ± 0.55 |

3.76 ± 0.61 |

0.570 |

| 9 |

3.70 ± 0.68 |

3.64 ± 0.70 |

3.76 ± 0.66 |

0.613 |

| 10 |

3.56 ± 0.64 |

3.44 ± 0.65 |

3.68 ± 0.62 |

0.296 |

| 11 |

3.72 ± 0.83 |

3.72 ± 0.93 |

3.72 ± 0.73 |

0.975 |

| 12 |

2.98 ± 0.77 |

2.76 ± 0.66 |

3.20 ± 0.82 |

0.054 |

| 13 |

3.46 ± 0.84 |

3.24 ± 0.88 |

3.68 ± 0.75 |

0.089 |

| 14 |

2.86 ± 0.83 |

2.88 ± 0.88 |

3.84 ± 0.80 |

0.877 |

| 15 |

4.26 ± 0.78 |

4.24 ± 0.60 |

4.28 ± 0.94 |

0.412 |

| 16 |

3.62 ± 1.07 |

3.48 ± 1.12 |

3.76 ± 1.01 |

0.357 |

| 17 |

3.84 ± 0.71 |

3.84 ± 0.74 |

3.84 ± 0.69 |

0.982 |

| 18 |

3.84 ± 0.68 |

3.84 ± 0.62 |

3.84 ± 0.75 |

0.857 |

| 19 |

3.88 ± 0.75 |

3.80 ± 0.82 |

3.96 ± 0.67 |

0.627 |

| 20 |

3.80 ± 0.83 |

3.68 ± 0.94 |

3.92 ± 0.70 |

0.415 |

| 21 |

3.54 ± 0.95 |

3.72 ± 0.98 |

3.36 ± 0.91 |

0.071 |

| 22 |

3.74 ± 0.80 |

3.56 ± 0.82 |

3.92 ± 0.76 |

0.122 |

| 23 |

3.78 ± 0.82 |

3.64 ± 0.76 |

3.92 ± 0.86 |

0.176 |

| 24 |

3.28 ± 1.23 |

2.88 ± 1.20 |

3.68 ± 1.14 |

0.017 |

| 25 |

3.66 ± 0.96 |

3.24 ± 1.16 |

4.08 ± 0.40 |

0.002 |

| 26 |

2.06 ± 0.62 |

2.08 ± 0.81 |

2.04 ± 0.35 |

0.840 |

Table 4 - Comparison of the WHOQOL-BREF items between groups.

DISCUSSION

The mean patient age at the time of surgery was 67 years. One study of 6,786

elderly patients who underwent CS indicate that 88.7% were women, with an

average age of 68 years, similar to the findings in the present study16.

The same study reported that elderly patients who underwent CS were between 65

and 75 years of age (95%), indicating that the demand for CS by octogenarians is

much lower. In the sample of the present study, the majority (80%) underwent CS

at ages between 60 and 70 years, with no record of octogenarians. This finding

may be related to cultural factors that discourage CS beyond a certain age.

The prevalence of comorbidities among elderly women surveyed showed no

significant differences between the groups (p < 0.05). A

study in 200817 stated that society is

increasingly concerned with appearance, and that most people consider CS to be

quick and safe, not hesitating to resort to surgery to improve self-image.

Thus, one can conclude that the presence of comorbidities is not an impediment to

CS, which is considered safe. However, there are inherent risks in any surgery,

and the plastic surgeon has to be thorough in preoperative evaluation and

surgical planning.

The most popular types of surgery requested by the elderly in this study were

abdominoplasty (body) and blepharoplasty (facial). Younger patients prefer body

surgeries, particularly breast enlargement and liposuction, while elderly

patients prefer facial surgeries18. The

present study revealed an equal preference for facial and body surgeries among

the elderly, which can be explained by the fact that Brazil is a tropical

country, where the opportunities for exposure of the body are more frequent.

It was found that 36% of elderly patients had 1 cosmetic surgery, while 64% had

more than 1; surgeries were concomitant, or performed at different times. The

complexity of surgery and surgical time greater than 4 hours were the main risk

factors associated with postoperative complications19; there was no significant association with variables

such as sex, age, nutritional status, sedentary lifestyle, or the presence of

comorbidities. Another study found no significant difference in the risk of

complications associated with CS in elderly and young patients16, suggesting that CS may be performed in

both with equal safety.

The average number of CS procedures performed in each patient in this study was

2.16, which demonstrates the desire of the elderly to surgically correct several

body areas, the understanding of CS as a safe procedure, and the verification

that postoperative recovery may not be difficult.

The few postoperative complications (16%) found in this study were considered

minor, since their management was done on an outpatient basis and not in a

hospital environment. Seroma (8%) and dehiscence (12%) were the most common, in

contrast to the literature, which identified hematoma and infection as the most

frequent complications16,19. Six patients (24%) requested surgical

revision to improve the cosmetic result. In the majority of cases, these were

revisions for unsightly scars.

From the analysis of motivations for undergoing CS, it is clear that eliminating

the physical discomfort caused by changes in body shape, the desire to improve

QOL, and the desire for improved self-esteem are important in this phase of

life. A review of 48 studies published between 2000 and 200717, with the objective of identifying the

motivations for CS, revealed psychological, psychosocial, and psychiatric

factors, which were summarized as problems with self-image, self-esteem, social

isolation because of appearance (bullying), and dysmorphophobia.

This study identified the presence of a significant physical factor, i.e.,

discomfort caused by the shape of a body region (60%), as a reason for CS. This

finding was also cited in a study in Rio de Janeiro4, which found that 26% of respondents of all ages cited

this factor as a motivator, especially among candidates for reduction

mammoplasty and abdominoplasty, indicating that large breast or abdominal size

is a cause of physical discomfort.

Physical discomfort was cited by 60% of the elderly as a motivation for CS, and

92% reported high or very high personal satisfaction, suggesting resolution of

physical discomfort. In addition, 60% of the elderly women cited improvement of

self-image as an important reason for CS, and 84% said they had improved

self-image after CS.

This study highlights the positive impact of CS in the life of the elderly, with

significant improvement over preoperative expectations when one considers the

perceived benefits. A desire for improvement of self-image may account for the

growth in the number of cosmetic procedures in the elderly in the last decade. A

4% increase in the demand for CS and 26% when all aesthetic procedures were

considered was reported among the elderly in the USA8.

Regarding the effect of CS in the relationship with a partner, only 20% of

elderly patients reported significant or very significant improvement, and few

(4%) cases were motivated by the desire to please another person. In contrast,

in a study by the Ivo Pitanguy Institute that included patients of all ages, 65%

reported an improvement of in relationship with a partner after CS4. Thus, there seems to be a difference in

the way relationships are valued with advancing age. The elderly in the present

study reported that CS was primarily chosen for personal benefit (92%),

improvement in self-image (84%), and enhancement of social interactions

(64%).

The present study showed no significant difference in the overall self-esteem

score between the groups. A study that evaluated self-esteem before and after

facial rejuvenation surgery20 showed no

significant differences in the group as a whole, but differences emerged when

the group was subdivided. Patients with low self-esteem preoperatively

experienced increased self-esteem after surgery; those with moderate self-esteem

did not show significant changes following CS; and those with high preoperative

self-esteem showed decreased self-esteem postoperatively, suggesting likely

preexisting depression, unrealistic expectations for surgery, or the presence of

a personality disorder.

Although all reported sustained rejuvenation benefit of approximately 9 years,

the positive outcome of surgery was not associated with improvement in

self-esteem, suggesting that there is a wide spectrum of possible psychological

reactions after CS.

In the current study, no elderly patients showed low self-esteem and the

prevalence of high self-esteem was greater in the case group (68% vs. 52% with

p = 0.387). The case group showed higher self-esteem scores

in items 4 and 8, which refer to self-sufficiency and self-respect. The

evaluation of these data shows that older people in general have good

self-esteem; however, CS seems to make the patient feel more capable, with

greater self-respect and an increase in self-worth.

Because they are more prone to loneliness, loss of family members, disease,

stress, cognitive loss, anxiety, and depression, the elderly are more

predisposed to a decrease in self-esteem. However, several studies5,21,22 confirm that

a significant percentage of patients who undergo CS experience increased

self-esteem, with decreased social withdrawal and enhanced ability to make

friends.

Every effort to eliminate loneliness in the elderly increases their self-esteem

and prevents psychological illness6.

Therefore, it can be argued that CS in the elderly is justified by contributing

to improvement in social interaction and prevention of psychological disorders

such as anxiety and depression.

This study also showed no difference in global QOL or physical, psychological,

and social domains between the groups. In contrast, a literature review3 reported that CS improves QOL. Another

author who only assessed patients in the postoperative period reported that

improvement in QOL is a consistent reason for undergoing CS23. Their results indicated that 84% of patients were

satisfied or very satisfied with the result and that 88.9% would recommend the

surgery to a friend.

Two hypotheses emerge from the present study. Either the WHOQOL-BREF cannot

detect changes caused by CS (responsiveness), or the assessment of QOL in the

elderly is different from that in other age groups. This suggests that the

elderly may have an idealized or unrealistic expectation of improvement from

CS.

Despite the methodological difficulties in the present study, which may be

related to the concomitant evaluation of various types of CS, the population of

patients analyzed, and the use of validated, but nonspecific questionnaires, the

importance of studies involving cosmetic procedures in the elderly has been

demonstrated.

CONCLUSION

The average age of elderly patients who underwent CS was 67 years, and most had

mid-level education. The elderly also sought facial and body surgeries and the

occurrence of complications and need for reintervention was not higher than in

younger patients.

The motivations of the elderly to have CS were physical and psychological. The

level of personal benefit from CS was high and social life was improved.

Elderly women who underwent CS did not show improved QOL and self-esteem when

compared to those who did not undergo CS. However, when those who underwent CS

were analyzed separately, high levels of personal satisfaction and improvement

of social life were observed.

COLLABORATIONS

|

LMSP

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; data collection; concept and

design of the study; project management; methodology; writing and

preparation of the original; validation; review.

|

|

GAC

|

Final approval of the manuscript; project management;

supervision.

|

REFERENCES

1. Suzman R, Beard JR, Boerma T, Chatterji S. Health in an ageing

world--what do we know? Lancet. 2015;385(9967):484-6.

2. Papadopulos NA, Kovacs L, Krammer S, Herschbach P, Henrich G, Biemer

E. Quality of life following aesthetic plastic surgery: a prospective study. J

Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(8):915-21.

3. Dreher R, Blaya C, Tenório JL, Saltz R, Ely PB, Ferrão YA. Quality

of Life and Aesthetic Plastic Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4(9):e862.

4. Tournieux TT, Aguiar LFS, Almeida MWR, Prado LFAM, Radwanski HN,

Pitanguy I. Estudo prospectivo da avaliação da qualidade de vida e aspectos

psicossociais em cirurgia plástica estética. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2009;24(3):357-61.

5. Poli Neto P, Caponi SNC. A medicalização da beleza. Interface

(Botucatu). 2007;11(23):569-84.

6. Molavi R, Alavi M, Keshvari M. Relationship between general health

of older health service users and their self-esteem in Isfahan in 2014. Iran J

Nurs Midwifery Res. 2015;20(6):717-22.

7. Ferreira MC. Cirurgia Plástica Estética - Avaliação dos Resultados.

Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2000;15(1):61-6.

8. American Society of Plastic Surgeons - ASPS. Cosmetic Plastic

Surgery Statistics. 2016. [acesso 2018 Jan 31]. Disponível em: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/news/plasticsurgery-statistics

9. http://www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br/wpcontent/uploads/2017/12/CENSO- 2017.pdf

10. Lima LCV, Villela WV, Bittar CML. Entrevistas com idosos: percepções

de qualidade de vida na velhice. Invest Qualit Saúde.

2016;2:57-65.

11. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A

practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician.

J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189-98.

12. Brucki SMD, Nitrini R, Caramelli P, Bertolucci PHF, Okamoto IH.

Sugestões para o uso do mini-exame do estado mental no Brasil. Arq Neuro

Psiquiatr. 2003;61(3B):777-81.

13. Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Self Image. Princeton:

Princeton University Press; 1965.

14. Greenberger E, Chen C, Dmitrieva J, Farruggia SP. Item-wording and

the dimensionality of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale: do they matter? Pers

Individ Dif. 2003;35(6):1241-54.

15. Kluthcovsky ACGC, Kluthcovsky FA. O WHOQOL-bref, um instrumento para

avaliar qualidade de vida: uma revisão sistemática. Rev Psiquiatr. 2009;31(3.

Suppl):1-12.

16. Yeslev M, Gupta V, Winocour J, Shack RB, Grotting JC, Higdon KK.

Safety of Cosmetic Procedures in Elderly and Octogenarian Patients. Aesthet Surg

J. 2015;35(7):864-73.

17. Haas CF, Champion A, Secor D. Motivating factors for seeking

cosmetic surgery: a synthesis of the literature. Plast Surg Nurs.

2008;28(4):177-82.

18. International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery - ISAPS. Global

Statistics. 2016. [acesso 2018 Jan 31]. Disponível em: https://www.isaps.org/medicalprofessionals/isaps-global-statistics/

19. Saldanha OR, Salles AG, Llaverias F, Saldanha Filho OR, Saldanha CB.

Predictive factors for complications in plastic surgery procedures - suggested

safety scores. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;29(1):105-13.

20. Jacono A, Chastant RP, Dibelius G. Association of Patient

Self-esteem With Perceived Outcome After Face-lift Surgery. JAMA Facial Plast

Surg. 2016;18(1):42-6.

21. Pusic AL, Lemaine V, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Cano SJ. Patient-reported

outcome measures in plastic surgery: use and interpretation in evidence-based

medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(3):1361-7.

22. Sante AB, Pasian SR. Imagem corporal e características de

personalidade de mulheres solicitantes de cirurgia plástica estética. Psicol

Reflex Crit. 2011;24(3):429-37.

23. Papadopulos NA, Staffler V, Mirceva V, Henrich G, Papadopoulos ON,

Kovacs L, et al. Does abdominoplasty have a positive influence on quality of

life, self-esteem, and emotional stability? Plast Reconstr Surg.

2012;129(6):957e-62e.

1. Universidade Católica de Brasília, Brasília,

DF, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Lenise Maria Spadoni-Pacheco, QND 22M CASA

11, Brasília, DF, Brasil, Zip Code 72120-220. E-mail:

lenisespadoni@hotmail.com

Article received: August 17, 2018.

Article accepted: November 11, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.