INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is an important public health condition, the most prevalent female

cancer excluding non-melanoma skin cancers, and the second cause of cancer death

in women behind only lung cancer.

According to the American Cancer Society, there were an

estimated 316,120 new cases of breast cancer in the United States in 20171. According to data from the National

Cancer Institute, there were an estimated 57,960 new cases of breast cancer in

Brazil in 20162.

The mortality rate is stable in women aged less than 50 years but has been

decreasing in older women, probably due to greater access to information for a

part of the population, early diagnosis, and improved treatment modalities3.

Mastectomy is an essential part of the treatment for breast cancer. The

reconstruction of the breast helps affected women better preserve their

self-esteem and is a right warranted by law in Brazil since 19994. Breast reconstruction does not interfere

with the sequential steps in cancer treatment and does not compromise the

detection of local recurrence5. Several

breast reconstruction techniques have been described, with individualized

assessments defining the technique best suited for each patient.

The use of the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap (LDMF) to cover defects caused

by mastectomy was initially described by Tansini in 1906. However, it was not

until 1978 that this flap was used for the reconstruction of the breast by

Bostwick6.

Since then, the LDMF technique has become a mainstay in breast plastic surgery.

The use of silicone breast implants has helped restore the volume of

reconstructed breasts, since the flap itself does not usually provide sufficient

soft parts to recreate the breast mound. Since the latissimus dorsi muscle is

located in the posterior portion of the trunk, its use for breast reconstruction

would usually require a change of decubitus position during the surgical

procedure, which would imply an increase in surgical time.

The performance of this surgery in a lateral decubitus position has the advantage

of eliminating the change of decubitus position, and as a result, the procedure

is shorter. However, anatomical familiarization is required by the surgeon, not

only with regard to the structures to be dissected, but also to the position in

which the flap is sutured to the receptor site and the suitability for better

customization of the remaining breast skin envelope.

The systematization of this procedure in the lateral decubitus position involves

several aspects, from the positioning of the patient on the surgical table to a

description of the details of dissection and customization of the skin island

and envelope. A predetermined sequence is then configured, without change of the

decubitus position, to reduce the duration of the surgery without affecting the

final result.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to present a surgical systematization with the

description of a series of cases.

METHOD

This was a retrospective primary study conducted using the medical records and

photographic documentation of patients who underwent breast reconstruction with

the LDMF with a silicone implant in the lateral decubitus position between

October 2015 and April 2017. The patients were operated on by the author in

both, a private clinic and two public services where he is a plastic surgeon

(Hospital Napoleão Laureano-PB and Hospital das Clínicas-PE). The principles of

the Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2000, and Resolution 196/96 of the

National Health Council were duly followed.

Inclusion criteria

Patients who underwent mastectomy due to breast cancer underwent immediate or

delayed breast reconstruction using the LDMF with a silicone implant in the

single lateral decubitus position between October 2015 and April 2017 and

were operated on by the author were included in this study.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who were smokers, had a body mass index greater than or equal to 30

kg/m2, and/or missed the minimum 3-month postoperative

follow-up were excluded from this study.

Surgical systematization

The patient should be positioned in a lateral decubitus position with the

ipsilateral limb abducted at 90 degrees and attached to a fabric-coated arc

through a bandage. Small cushions must be placed below the chest, between

the knees, and to support the head. The hip should be stabilized on the

surgical table with a wide bandage or band suitable for a lateral decubitus

surgery. Thermal blankets and gradual pneumatic-compression leggings are

recommended. The skin island on the dorsum is transversally marked with its

axis following the projection of the corresponding inframammary sulcus,

which ensures that the final scar is hidden in the posterior loop of the

brassiere (Figure 1).

Figura 1 - Positioning of the patient.

Figura 1 - Positioning of the patient.

Further orientations of the skin island can be projected based on the

location of the chest defect. The dimensions usually measure 17 × 7 cm. If

the reconstruction is delayed, surgery is initiated by the removal of the

scar prior to the mastectomy. This is followed by the dissection of the

receptor site at a level along the fascia of the greater pectoral muscle

inferiorly until the projection of the anterior inframammary sulcus,

superiorly up to about 3 cm from the clavicle, medially up to 1.5 cm from

the sternal border, and laterally up to the projection of the midaxillary

line.

In cases of immediate reconstruction, surgery begins with a skin island

incision that preserves some of Scarpa’s fascia superiorly and inferiorly to

the skin island, and then dissecting to the plane closest to the latissimus

dorsi muscle. The dissection should extend medially to the palpation of the

vertebral transverse processes, laterally just beyond the border between the

large dorsal and anterior serratus muscles, and inferiorly until the

identification of the aponeurotic expansion of the latissimus dorsi muscle

near the iliac crest.

The superior dissection is performed later with the aid of the Nelson forceps

and an electric scalpel. The lateral insertion of the latissimus dorsi

muscle is released within the limits already dissected; the muscle is

released to the inferior limit and upon lifting the released muscle, it

becomes easy to incise its origin along the spine. At this time, the muscle

is flat and wide, with its characteristic median thickness.

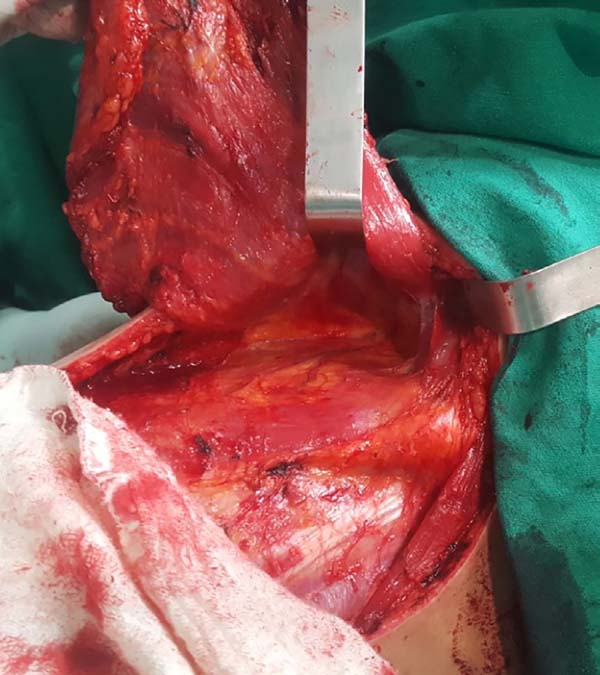

When ascending the dissection, it is important to identify and preserve the

donor site structures that are not necessary for the reconstruction,

including the fatty fascia behind the latissimus dorsi muscle and the

portion of the trapezius muscle that overlaps medially (Figure 2). Once these structures are preserved, the

dissection of the latissimus dorsi muscle must be complemented up to near

its insertion in the humerus, being its release is optional, with a risk of

torsion of the pedicle in certain cases; the advantage, however, is the

reduced final volume of tissues in the axillary region.

Figura 2 - Fatty fascia behind the latissimus dorsi muscle.

Figura 2 - Fatty fascia behind the latissimus dorsi muscle.

At this time, the muscle should already be fully released in its inferior and

medial portions, requiring only the lateral release, which should be

carefully performed near the axillary region, since the pedicle with the

thoracodorsal vessels is located in this region. The anatomical detail is

that this release should occur over the muscle as the pedicle penetrates

through its deep surface, and the dissection in this deep plane may extend a

little beyond the vascular anatomical finding called the “goose foot”, which

contains branches destined for the anterior serratus muscle and denotes

proximity to the thoracodorsal pedicle (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Elevated flap showing the anatomical finding known as “goose

foot”.

Figure 3 - Elevated flap showing the anatomical finding known as “goose

foot”.

With the muscle dissected, a tunnel of approximately 6 cm width is created

through the axillary fascia, approximately at the height of the line of

deployment of the axillary hair (Figure 4). Taking care not to twist the muscle, the same is rotated to

the receptor site through the previous traction using the Allis forceps

(Figure 5).

Figura 4 - Dissected flap with preserved pedicle and infra-axillary

tunnel in the upper portion.

Figura 4 - Dissected flap with preserved pedicle and infra-axillary

tunnel in the upper portion.

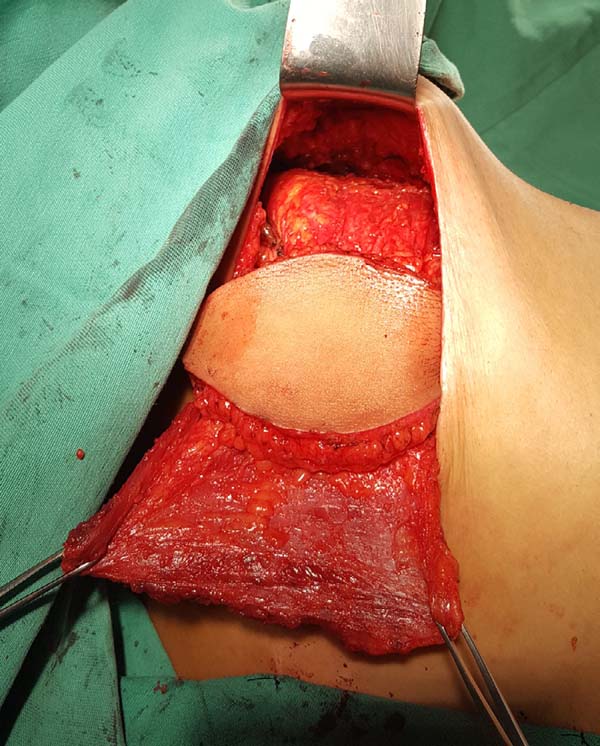

Figure 5 - Flap rotated to the receptor site and ready to be sutured;

preparation of a pocket for the silicone implant.

Figure 5 - Flap rotated to the receptor site and ready to be sutured;

preparation of a pocket for the silicone implant.

At this moment, the donor site can be synthesized with vicryl 2.0 adhesion

sutures and aspiration drainage with 4.8-gauge drains. The pocket for the

breast implant is created by attaching the muscle to the limits dissected

using nylon 2.0 sutures.

The implant is bathed in an antibiotic solution with cefazolin (1 g) and

gentamicin (80 mg) and then positioned in the pocket with a conclusion of

the suture. The skin island and the remaining breast skin envelope should be

customized so that the neobreast has a slight ptosis, which gives a more

natural result (Figure 6). The

recipient site should also be drained with a 6.4-gauge suction drain. The

drains are removed postoperatively when the daily flow is less than 40

mL.

Figura 6 - Immediate appearance after customization of the flap and

mastectomy skin.

Figura 6 - Immediate appearance after customization of the flap and

mastectomy skin.

RESULTS

A total of 29 patients underwent surgery during the study period, with a minimum

post-operative follow-up duration of 3 months. The mean age of the patients was

47.22 years, with the youngest patient was aged 28 years and the oldest, 76

years (Table 1).

Table 1 - Distribution of age and volume of breast implants.

| Variable |

Maximum |

Minimum |

Average |

| Age |

76 years |

28 years |

47.22 years |

| Breast Implant |

390 cc |

280 cc |

318 cc |

Table 1 - Distribution of age and volume of breast implants.

None of the patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy. With respect to the

comorbidities detected, there were 3 patients with systemic hypertension and 1

patient with fibromyalgia (Table 2).

Table 2 - Distribution of comorbidities.

| Variable |

Absolute number |

Relative rate |

| Arterial hypertension |

3 |

10.5% |

| Fibromyalgia |

1 |

3.556% |

Table 2 - Distribution of comorbidities.

The timing of the reconstructive surgery was decided in conjunction with a team

of mastologists and included 26 immediate reconstructions and 3 late

reconstructions. There were no bilateral reconstructions. The implants used were

round format in 28 patients and anatomical in 1 patient. The volumes ranged from

260 cc to 390 cc, with an average of 318 cc. The average length of surgery was 1

h 45 m (Table 1).

The period of hospitalization was uniform with discharges on the second

postoperative day. The drains were removed when the daily flow fell below 40 mL,

with an average of 10 postoperative days but not exceeding 14 postoperative

days.

With respect to complications, there was one patient with a seroma in the

receptor site (3.5%), who also had a local infection without response to

antibiotic therapy, which resulted in extrusion of the breast implant.

One patient (3.5%) had partial necrosis of the skin island of the flap and local

cellulitis, with resolution after debridement, antibiotic therapy, and

dressings. The cause of necrosis can be attributed to the small cutaneous

segment detached from the muscle to better adapt to the receptor site defect.

Two patients (7.0%) suffered from the remnant cutaneous envelope of the breast

without major clinical repercussions. In these 3 patients, conservative measures

were sufficient since the mammary implant in this technique is completely

covered by the latissimus dorsi muscle and provides both protection in cases of

cutaneous necrosis and avoidance of external contamination.

One patient (3.5%) had extensive local recurrence and the implant was removed at

the request of the radiotherapy team according to a therapeutic rescue protocol.

One patient (3.5%), submitted to adjuvant radiotherapy, had a Baker III capsular

contracture after 18 months of breast reconstruction.

Four patients (14%) were submitted to scar reviews.

On clinical examination, one patient (3.5%) had a seroma in the dorsum that was

resolved with aspiration puncture. Imaging examinations were not requested

routinely to evaluate this condition.

Three patients (10.5%) displayed functional abduction limitations in the

articulation of the ipsilateral shoulder. One of these patients was diagnosed

with a winged scapula and forwarded to follow-up with a physiotherapist (Table 3).

Table 3 - Distribution of complications.

| Variable |

Absolute number |

Index on |

| Infection |

2 |

7.0% |

| Cutaneous necrosis |

3 |

10.5% |

| Implant extrusion |

1 |

3.5% |

| Removal of the implant |

1 |

3.5% |

| Seroma in receptor site |

1 |

3.5% |

| Seroma in donor site |

1 |

3.5% |

| Capsular contracture |

1 |

3.5% |

| Scar revision |

4 |

14% |

| Functional joint deficit |

3 |

10.5% |

Table 3 - Distribution of complications.

Postoperative results can be seen in Figures 7 to 9.

Figure 7 - Pre-operative and 6-month postoperative aspects. Late

reconstruction.

Figure 7 - Pre-operative and 6-month postoperative aspects. Late

reconstruction.

Figure 8 - Pre-operative and 3-month postoperative aspects. Immediate

reconstruction.

Figure 8 - Pre-operative and 3-month postoperative aspects. Immediate

reconstruction.

Figura 9 - Photographs of the patients in the sixth postoperative

month.

Figura 9 - Photographs of the patients in the sixth postoperative

month.

DISCUSSION

The surgical treatment of breast cancer has evolved over time. In 1894, Halstead

described the classical radical mastectomy as the first effective treatment for

breast cancer. In 1948 by comparative studies, Patey noted that the preservation

of the greater pectoral muscle does not compromise the local control of the

tumor, and this led to the term modified radical mastectomy.

To the extent that adjuvant systemic treatment has gained in importance,

conservative surgeries of the breast that preserve lymph nodes and segments of

the breast parenchyma became possible6,

leading to breast reconstruction efforts.

The LDMF was historically used to cover defects in the chest wall, either to

cover the defects arising from surgical breast excision or to treat sequelae

caused by radiotherapy. The advent of breast implants between the 1960s and

1970s helped to regain the lost breast volume when associated with the LDMF.

Techniques that rely exclusively on autologous tissues, such as the use of

transverse rectus abdominis muscle (TRAM), microsurgical flaps, and others that

use only alloplastic material positioned below the muscles of the anterior

thoracic region, have been described by surgeons who aimed for alternatives that

could be adapted for each patient.

The LDMF not only weathered time but also gained popularity and is now a mainstay

of a large number of plastic surgeons. There are a few anatomical variations of

the LDMF, which has reliable caliber pedicle and wide muscle width, which allows

full coverage of implants, including the bulky implants. Furthermore, morbidity

in the donor area is small, such as a functional deficit in the articulation of

the shoulder, seroma formation, or persistent back pain.

The applicability LDMF is vast, and the LDMF may be used for coverage in cases of

thin coverage of soft parts in the breast region, irradiated anterior chest

wall, previous resection of the pectoralis major, ptotic or small to moderate

size contralateral breast, previous unsuccessful reconstruction with exclusive

breast implant, previous surgeries in the abdomen, and lack of experience in

microsurgical techniques.

The skin island on the dorsum can be ample; however, the primary closure width

can be 9 cm with a length of 18 cm, but 17 × 7 cm flaps are suitable. Fat

compartments in the back were described in the 1990s by Delay et al.7, with the aim of incorporating a greater

quantity of fatty fascia in the flap and reconstructing small to medium sized

breasts without the need for implants. However, contour defects and seroma

formation in the donor area decreased interest in this technique8.

Moderate amounts of fat fascia can be mobilized to the LDMF for improving both

the consistency and outline of the neobreast, allowing for a smoother and

less-marked transition in its upper pole, as described by Tavares-Filho et

al.9. New generations of implants with

high-cohesive gel confer greater stability to the breast shape and better

consistency on touch, resulting in good esthetic results in reconstructions

performed with the LDMF, even without an excessive fatty fascia harvest10.

Breast reconstruction with the LDMF can be both delayed and immediate (at the

same time as the mastectomy). The decubitus for this surgery can vary. For

surgeons who choose to harvest the LDMF in a ventral decubitus, there is a need

to change the position of the patient at least once in cases of late

reconstruction or even twice in cases of immediate reconstruction.

When opting for a lateral decubitus, the position change occurs only once in

immediate reconstructions and becomes unnecessary in late reconstructions.

Changes in the decubitus position carry the risk of joint, ligament, or even

nerve lesions. In addition, they require more surgical material (new sterile

fields) and an increase in the total length of surgery with all its potential

morbid (infection, thromboembolic events, hypothermia, etc.) and financial

implications (surgical room time and anesthetic medications). Specific studies

are needed to quantify these variables.

The systematization of the surgical technique allows the surgeon to follow a

certain sequence, thus, minimizing the loss of time. Systematization begins with

the orientation and training of nursing assistants who will position the

patient, making this dynamic moment brief and safe. The surgical procedure is

then performed by following the described technique step-by-step; this ensures

that the assistant surgeon and the scrub nurse know the exact sequence of

presentation and the instruments used.

A disadvantage may be that some surgeons may take time to familiarize themselves

with the dissection in a position different from the usual dorsal decubitus, in

addition to difficulty in properly customizing the skin island and the remaining

breast skin envelope, which pend slightly medially. The end result can be a

satisfactory neobreast volume, but with excessive ptosis and/or markedly

eccentric positioning of the skin island.

Literature shows that the rate of complications for this surgery is low. A seroma

at the donor site is a fairly common complication with studies showing

complication rates that vary from 16% to 79%11. The association of adhesion sutures and aspiration drains may

account for the low seroma rate observed, which corroborates with the data

presented by Cammarota et al. 201612.

Other complications are described with lower rates of incidence: skin infections

account for 3.3% of the complications; flap necrosis, 1.3%; operative wound

dehiscence, 0.6%; and clinical complications, 3.2%12. A larger sample set would show better approximation of

the rate of complications observed with those previously reported.

The rates of capsular contracture are variable and range from 6% to 68%13,14. Longer follow-up duration is necessary to assess the

real contracture rate. Adjuvant radiotherapy may be associated with an increase

in the contracture rate resulting in actinic capsular contracture15.

An alternative for patients requiring adjuvant radiotherapy is the association of

LDMF with a breast tissue expander. A silicone implant would be used only occur

after complete tissue expansion and completion of radiotherapy, when it is

possible to adjust the format of the neobreast and correct the possible

contracture stigmas by capsulotomy or capsulectomy16,17.

Plastic surgery options have evolved; therefore, fewer morbidities are associated

with these patients. The use of microsurgical flaps or implants associated with

dermal matrices has been reported in recent years in specialized publications as

alternatives that promote low morbidity and good results4,18.

However, the use of microsurgical flaps requires specific prolonged surgical

training, and dermal matrices are still not feasible in Brazil due to the high

associated costs. Consequently, the LDMF in combination with silicone implants

continues to be an excellent option for plastic surgeons.

CONCLUSION

The systematization of breast reconstruction using the LDMF combined with

silicone breast implants in the lateral decubitus position is a safe alternative

for the plastic surgeon, which is a rapid procedure with consistent results.

These advantages can be availed when the medical professionals are familiar with

the surgery in this patient positioning.

COLLABORATIONS

|

ICGL

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; conception and design of the

study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments.

|

REFERENCES

1. American Cancer Society. How Common Is Breast Cancer? [acesso 2017

Jun 1]. Disponível em: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/breast-cancer/about/how-common-is-breast-cancer.html

2. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José

Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Câncer de Mama. Estimativa de novos casos.

[acesso 2017 Jun 1]. Disponível em: http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/tiposdecancer/site/home/mama/cancer_mama++

3. Secretaria de Comunicação Social do Senado Federal. Lei Garante

Reconstrução da Mama em Seguida à Retirada de Câncer. [acesso 2017 Jun 1].

Disponível em: http://www12.senado.leg.br/noticias/materias/2013/05/07/lei-garante-reconstrucao-da-mama-em-seguida-a-retirada-de-cancer

4. Macadam SA, Bovill ES, Buchel EW, Lennox PA. Evidence-Based

Medicine: Autologous Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2017;139(1):204e-29e. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002855

5. Wei FC, Mardini S. Retalhos e cirurgia plástica reconstrutora. Rio

de Janeiro: Di Livros; 2012. p. 343-64.

6. Gabka CJ, Bohmert H. Cirurgia plástica e reconstrutiva da mama. 2ª

ed. Porto Alegre: Artmed; 2010.

7. Delay E, Gounot N, Bouillot A, Zlatoff P, Rivoire M. Autologous

latissimus breast reconstruction: a 3-year clinical experience with 100

patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(5):1461-78. PMID: 9774000 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199810000-00020

8. Heitmann C, Pelzer M, Kuentscher M, Menke H, Germann G. The extended

latissimus dorsi flap revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(5):1697-701.

PMID: 12655217 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000055444.84307.75

9. Tavares-Filho JM, Franco D, Moreto L, Porchat C, Franco T.

Utilização do retalho miocutâneo de grande dorsal, com extensão adiposa, nas

reconstruções mamárias: uma opção para preenchimento do polo superior. Rev Bras

Cir Plást. 2015;30(3):423-8.

10. D'Alessandro GS, Povedano A, Santos LKIL, Santos RA, Góes JCS.

Reconstrução mamária imediata com retalho do músculo grande dorsal e implante de

silicone. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(2):163-71.

11. Roy MK, Shrotia S, Holcombe C, Webster DJ, Hughes LE, Mansel RE.

Complications of latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap breast reconstruction. Eur J

Surg Oncol. 1998;24(3):162-5. PMID: 9630851 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0748-7983(98)92810-4

12. Cammarota MC, Ribeiro Junior I, Lima RQ, Almeida CM, Moura LG, Daher

LMC, et al. Estudo do uso de pontos de adesão para minimizar a formação de

seroma após mastectomia com reconstrução imediata. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2016;31(2):158-65.

13. Gart MS, Smetona JT, Hanwright PJ, Fine NA, Bethke KP, Khan SA, et

al. Autologous options for postmastectomy breast reconstruction: a comparison of

outcomes based on the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality

Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(2):229-38.

14. Perdikis G, Koonce S, Collis G, Eck D. Latissimus dorsi myocutaneous

flap for breast reconstruction: bad rap or good flap? Eplasty.

2011;11e39.

15. McCarthy CM, Pusic AL, Disa JJ, McCormick BL, Montgomery LL,

Cordeiro PG. Unilateral postoperative chest wall radiotherapy in bilateral

tissue expander/implant reconstruction patients: a prospective outcomes

analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(6):1642-7. PMID:

16267426

16. Losken A, Nicholas CS, Pineel XA, Carlson GW. Outcomes evaluation

following breast reconstruction using latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flaps. Ann

Plast Surg. 2010;65(1):17-22.

17. Lennox PA, Bovill ES, Macadam AS. Evidence-Based Medicine:

Alloplastic Breast Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2017;140(1):94e-108e.

18. Qureshi AA, Broderick KP, Belz J, Funk S, Reaven N, Brandt KE, et

al. Uneventful versus Successful Reconstruction and Outcome Pathways in

Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction with Acellular Dermal Matrices. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(2):173e- 83e.

1. Hospital Napoleão Laureano, João Pessoa, PB,

Brazil

2. Hospital das Clínicas, Recife, PE,

Brazil.

3. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Igor Chaves Gomes

Luna, Rua Reinaldo Tavares de Melo, 142 - Manaíra - João Pessoa, PB,

Brazil. Zip Code 58038-300. E-mail:

igorluna_med@hotmail.com

Article received: June 10, 2017.

Article accepted: September 18, 2017.

Conflicts of interest: none.