INTRODUCTION

Breast augmentation is the most commonly performed cosmetic surgery in the United

States and second in Brazil and worldwide1,2. Although

symmastia might have rare congenital causes, it usually results from a

complication of breast augmentation due to incorrect medial placement of

implants, which approach too closely or cross the midline, causing intermammary

sulcus loss3-5.

There are no reports in the literature regarding the incidence of iatrogenic

symmastia5. The diagnosis is

essentially clinical. It has a spectrum of intensity of symptoms, from mild

cases that go unnoticed to severe cases presenting important psychosocial

repercussions.

The main associated factors are excessive dissection of the implant plane toward

the sternum, excessive division of the medial insertion of the pectoralis major

muscle, use of implants with excessive diameter or volume, congenital symmastia,

and presence of lateral anomalous bundles of the pectoralis minor muscle4. Some factors can generally be controlled

by the surgeon, and iatrogenic symmastia can be prevented through subtle medial

dissection, which thereby prevents excessive volume or very close positioning

to

the midline4-6.

Complications such as seromas, hematomas, infections, or other factors that lead

to an increase in the pressure of plane or even a tissue adhesion rupture in

the

medial region of the plane also increase the risk of symmastia.

ObjeCtivE

To describe the experience and approach for the surgical treatment of iatrogenic

symmastia.

CASE REPORT

Work type: case series. Two patients underwent surgical symmastia repair after

breast augmentation with implants.

Patient 1

A 28-year-old patient underwent breast augmentation performed by another

surgeon with 280-mL high-profile silicone implants (retroglandular) in 2008,

and symmastia occurred. In 2009, the same surgeon changed the plane to

retromuscular, and the symmastia recurred (Figures 1 and 2).

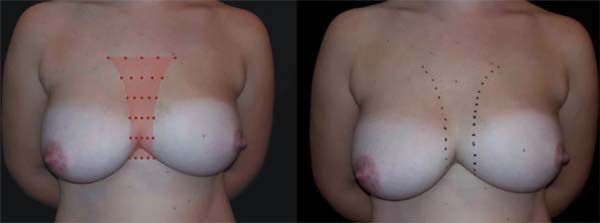

Figure 1 - Patient with visible symmastia even in static

situation.

Figure 1 - Patient with visible symmastia even in static

situation.

Figure 2 - Total loss of the intermammary sulcus in a dynamic

maneuver.

Figure 2 - Total loss of the intermammary sulcus in a dynamic

maneuver.

In 2016, she underwent surgical symmastia repair performed by the senior

author of this article. A vertical band on the sternum, approximately 4 cm

wide, was drawn (Figure 3). The access

route used was the inframammary sulcus, over a previous scar. The implants

were removed (Figure 4), and the

capsule on its anterior and posterior bands was scarified by electrocautery

(power 40, cauterization mode, electrocautery brand

Valleylab®).

Figure 3 - Marking of the region on the sternum.

Figure 3 - Marking of the region on the sternum.

Figure 4 - Implant removal, scarification of capsule surfaces, and

beginning of adhesion points.

Figure 4 - Implant removal, scarification of capsule surfaces, and

beginning of adhesion points.

Adhesion sutures were made with 3-0 nylon thread between the anterior and

posterior capsule surfaces (close to the sternum fascia) (Figure 5). Four lines with 6 sutures

each were made, comprising a vertical band approximately 4 cm wide; 420-mL

round, super-high-projection implants were inserted in the same plane (Figure 6). Delimitation and separation

of the planes was obtained, with an improved positioning of the implants, 60

days post-operatively (Figure 7).

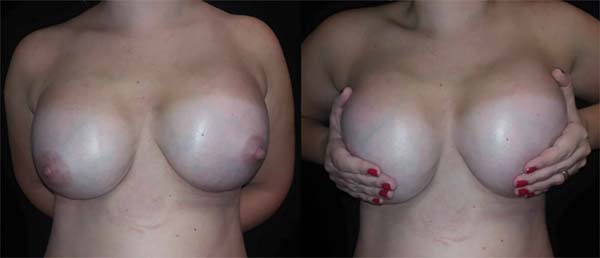

Figure 5 - Total closure of the space between the 2 planes.

Figure 5 - Total closure of the space between the 2 planes.

Figure 6 - Post-implant placement on the left (superoinferior view).

Delimitation of the left area is observed when lateralizing the

implant.

Figure 6 - Post-implant placement on the left (superoinferior view).

Delimitation of the left area is observed when lateralizing the

implant.

Figure 7 - Sixty days after surgery. Properly lateralized implants,

despite the maneuver to press them medially.

Figure 7 - Sixty days after surgery. Properly lateralized implants,

despite the maneuver to press them medially.

Patient 2

A 19-year-old patient underwent breast augmentation with 300-mL

retromuscular, round, high-projection implants in January 2016. This

procedure was performed by the senior author of the article. The patient

developed seroma and infection of the surgical site, requiring the removal

of the implants. Six months later, after she underwent new breast

augmentation, with implants of the same volume and maintaining the

retromuscular plane, symmastia occurred (Figure 8).

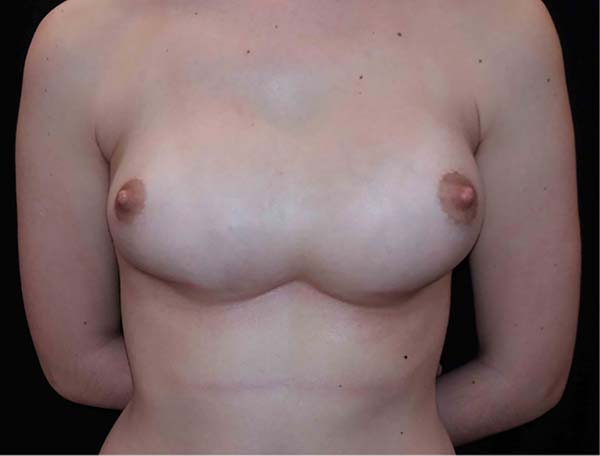

Figure 8 - Total loss of the intermammary sulcus after augmentation

mammoplasty with implants.

Figure 8 - Total loss of the intermammary sulcus after augmentation

mammoplasty with implants.

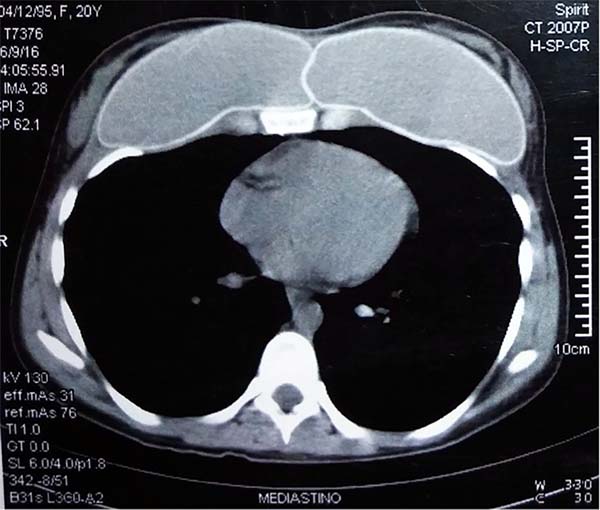

Computed tomographic examination showed total union of the planes and

medialization of the implants (Figure 9). A 2-step approach was proposed: in the first procedure, the

implants were removed, with the creation of a new medial sulcus using the

same technique (scarification of the capsule surfaces, creation of a

separation band approximately 4 cm between the planes, and creation of

adhesion sutures with nylon 3-0 thread) (Figures 10 and 11). After

3 months, 280-mL round, super-high-projection breast implants were placed in

the same plane, achieving symmastia repair and appropriate esthetic outcome

(Figure 12).

Figure 9 - CT scan showing implant plane unification.

Figure 9 - CT scan showing implant plane unification.

Figure 10 - Transoperative. Complete loss of separation between

planes.

Figure 10 - Transoperative. Complete loss of separation between

planes.

Figure 11 - Adhesion points between capsules.

Figure 11 - Adhesion points between capsules.

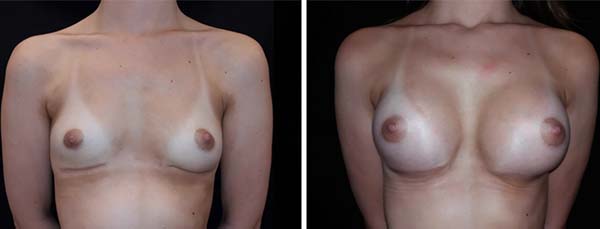

Figure 12 - Left: Post-implant removal and generation of the intermammary

sulcus. Right: Post-implant replacement (70 days after

surgery).

Figure 12 - Left: Post-implant removal and generation of the intermammary

sulcus. Right: Post-implant replacement (70 days after

surgery).

For both patients, there was no recurrence during follow-ups at 9 and 11

months, respectively, for cases 1 and 2.

DISCUSSION

Identification of risk factors for preoperative symmastia and transoperative care

are fundamental to avoid symmastia. Medial dissection should not exceed the

horizontal distance of 1.5 to 3 cm from the midpoint between the sternum angle

and the xiphoid process5.

Implants should not have dimensions that are extrapolated, as the literature

shows that most symmastia cases are associated with implants with excessive

diameter or volume4,5,7. The defect causing symmastia is usually found in the central

part. Cases of symmastia in the upper and lower parts are rarer5.

The diagnosis, in most of the cases, is evident and well defined, within 6 months

after the primary procedure. In milder cases, maneuvers such as application of

lateral pressure to both implants emphasize their anterior projection in the

presternal region4,5. There are few studies in the literature

on symmastia, and most of them are case series (Table 1).

Table 1 - Articles found in the literature on symmastia.

| Author |

Year |

Journal |

Number of cases |

| Becker |

2005 |

Plastic Reconstrutive Surgery |

5 |

| Spear |

2006 |

Plastic Reconstrutive Surgery |

20 |

| Spear et al.13 |

2009 |

Plastic Reconstrutive Surgery |

23 |

| Moliver et al.4 |

2015 |

Aesthetic Surgery Journal |

18 |

Table 1 - Articles found in the literature on symmastia.

These works proposed different surgical techniques for the treatment. There is

some agreement that the approach should be performed in a periareolar or

inframammary manner, depending on the previous incision, for adequate operative

field. Simple capsulorrhaphy may be effective and consists basically of a medial

suture between the anterior and posterior edges of medial capsule, but despite

its simplicity, its use is not very recommended due to the large number of

recurrence cases reported7,8.

Lateral and/or upper capsulotomy may be associated with decreased tension at the

medial edge. Another simple surgical option is the use of presternal

transcutaneous sutures. Their use is debatable, since the area is at high risk

for keloid formation, especially in patients with darker skin tones, despite

being recommended to minimize scars in the region.

More complex capsulorrhaphy techniques have been described to decrease the risk

of recurrence. Instead of a simple suture, using anterior and posterior flaps

that overlap on the medial breast edge, providing greater support, is possible.

However, the execution depends on a well-defined and mature capsule8,9. Another option for greater medial support is the use of a

C-shaped acellular dermal matrix in the band, which is medially fixed. Such a

technique is simple, but it adds cost to the procedure, despite its questionable

benefits10.

Replacing the implant plan can be a treatment strategy. Retroglandular implants

can be relocated to the retromuscular plane, providing better implant

coverage11,12. Retromuscular implants can be relocated

to the retroglandular plane if there is enough subcutaneous coverage6.

When there is insufficient coverage, repositioning the implants in an

intermediate plane can be attempted. Spear et al.13 described good esthetic results in their series of 23 patients

with subpectoral implants, which they attributed to the creation of

neo-subpectoral regions, a new anterior and posterior plane to the capsule to

the pectoralis major muscle, with no cases of recurrence.

Our repair procedure proposal used sutures between the anterior and posterior

capsules under the medial sulcus, which is associated with the scarification

of

their surfaces and results in a good adherence between planes. Since there are

no transcutaneous sutures, we avoided the risk of keloid formation. We believe

that promoting adhesion between capsule surfaces, i.e., their scarification,

is

important. Electrocauterization was used with the aim of promoting local

inflammation and increasing the possibility of adhesions.

The patient in case 1, who had mammary ptosis, was evaluated for the need for

simultaneous mastopexy. Because of the complexity of managing several variables

and to prevent the risk of breast devascularization, we chose to correct only

symmastia and proposed to perform mastopexy at another time, depending on the

need.

We observed that skin adhesion to the presternal region in the medial portion of

the breasts and the creation of a new sulcus reduced excess skin, which we

attribute to a mathematical explanation: the skin, in a situation of symmastia

detected in a tomographic position (caudo-cranial), forms an almost straight

line between the nipples. With symmastia repair, part of the excess skin is used

when remaking the correct curvature of the medial poles of the breasts. We also

observed a medialization of the areola-papillary complex. Such management proved

to be successful and led to good esthetic results, with the patient being

satisfied after the first surgery, with no need for a second intervention thus

far.

Patient 2 presented with significant psychological impairment, due to 3

unsuccessful surgical interventions. Thus, the maintenance of a good

doctor-patient relationship was fundamental for the therapeutic success of the

case.

The literature suggests that in certain cases of difficult resolution of

symmastia, the removal of the implants is primarily the best option, as it can

immediately improve the esthetic aspect, giving the patient the closest

semblance to the anatomy she had before breast augmentation13. When replacing the implants, we chose to use

super-high-projection ones because they have a smaller base diameter, compared

with high-projection implants, and thus occupy a smaller horizontal space.

CONCLUSION

Iatrogenic symmastia is a rare condition that has serious repercussions for the

patient; hence, its prevention is fundamental. It is difficult to conclude which

is the best technique for the correction of this condition because few studies

were published, with only a small number of cases. Although our case series is

modest, considering that this is a relatively rare condition, we believe the

technique we described can be used in the treatment of this condition, which

is

complex and has a high rate of recurrence.

COLLABORATIONS

|

MP

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final

approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study;

completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript

or critical review of its contents.

|

|

FBF

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final

approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study;

completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript

or critical review of its contents.

|

|

EMZ

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final

approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study;

completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript

or critical review of its contents.

|

|

BDMG

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final

approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study;

completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript

or critical review of its contents.

|

|

FMFN

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final

approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study;

completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript

or critical review of its contents.

|

|

LMP

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final

approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study;

completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript

or critical review of its contents.

|

|

RSW

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final

approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study;

completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript

or critical review of its contents.

|

|

PBE

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final

approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study;

completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript

or critical review of its contents.

|

REFERENCES

1. American Society of Plastic Surgeons [Internet]. American Society of

Plastic Surgeons. 2017 [cited 24 May 2017]. Available from: https://www.plasticsurgery.org

2. Surgery I. ISAPS - Sociedade Internacional de Cirurgia Plástica

Estética (ISAPS) [Internet]. Isaps.org. 2017 [cited 24 May 2017]. Available

from: http://www.isaps.org/pt/

3. Brown MH, Somogyi RB, Aggarwal S. Secondary Breast Augmentation.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(1):119e-35e. PMID: 27348674 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002280

4. Moliver CL, Sanchez ER, Kaltwasser K, Sanchez RJ. A Muscular

Etiology for Medial Implant Malposition Following Subpectoral Augmentation.

Aesth Surg J. 2015;35(7):NP203-10. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjv072

5. Selvaggi G, Giordano S, Ishak L. Synmastia: prevention and

correction. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;65(5):455-61. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181d37648

6. Lesavoy MA, Trussler AP, Dickinson BP. Difficulties with subpectoral

augmentation mammaplasty and its correction: the role of subglandular site

change in revision aesthetic breast surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2010;125(1):363-71. PMID: 20048627 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c2a4b0

7. Foustanos A, Zavrides H. Surgical reconstruction of iatrogenic

symmastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(3):143e-144e. PMID: 18317108 DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000300199.69982.48

8. Yoo G, Lee PK. Capsular flaps for the management of malpositioned

implants after augmentation mammoplasty. Aesth Surg J. 2010;34(1):111-5. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00266-009-9456-3

9. Parsa FD, Koehler SD, Parsa AA, Murariu D, Daher P. Symmastia after

breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(3):63e-65e. PMID: 21364388

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31820635b5

10. Curtis MS, Mahmood F, Nguyen MD, Lee BT. Use of AlloDerm for

correction of symmastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(4):192e-193e. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ea92a3

11. Harley OJ, Arnstein PM. Retrocapsular pocket to correct symmastia.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(1):329-31. PMID: 21701362 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182174661

12. Parsa FD, Parsa AA, Koehler SM, Daniel M. Surgical correction of

symmastia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(5):1577-9. PMID: 20440189 DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181d513f0

13. Spear SL, Dayan JH, Bogue D, Clemens MW, Newman M, Teitelbaum S, et

al. The "neosubpectoral" pocket for the correction of symmastia. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 2009;124(3):695-703. PMID: 19363454 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a8c89d

1. Universidade Federal de Ciências da Saúde de

Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

2. Santa Casa de Misericórdia de Porto Alegre,

Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

3. Universidade de Passo Fundo, Passo Fundo, RS,

Brazil.

4. Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande

do Sul, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

5. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo,

SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Felipe Bilhar

Fasolin

Rua General Lima e Silva, 757, apto 1207 - Cidade Baixa

Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil Zip Code 90050-101

E-mail: felipefasolin@hotmail.com

Article received: October 09, 2017.

Article accepted: May 17, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.