INTRODUCTION

Patients with severe obesity achieve greater and more sustained weight loss through

bariatric surgery when compared to non-surgical approaches. Regardless of the technique

chosen, the surgical procedure improves comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension

and health-related quality of life. With the increasing number of patients with massive

weight loss, there is also an increase in the demand for body contouring surgeries1. After massive weight loss, patients commonly have redundant skin folds, which can

lead to intertrigo, ulceration, infection, and mobility-related challenges2. Despite successful weight loss, a patient’s body image and psychological state after

bariatric surgery can deteriorate substantially3.

Although the need for surgery is more evident in individuals who have experienced

massive weight loss, an individual without significant weight loss may have a similar

deformity. Strict selection criteria may limit access to individuals who would benefit

from body contour correction; however, loose criteria can overwhelm the health system

and thus also restrict patients’ access to the service. Surgical procedures performed

on a patient with significant weight loss are complex, demand intense work from the

health team and have high rates of complications4,5.

According to Ordinance No. 425/GM/MS of March 19, 2013, patients undergoing reduction

gastroplasty with adherence to postoperative follow-up may undergo reconstructive

plastic surgery by the Unified Health System (SUS). Among the indications, we have

recurrent skin infections due to excess skin, such as fungal and bacterial infections;

psychopathological changes due to weight reduction; limitation of professional activity

due to weight and impossibility of movement6. As a contraindication of reconstructive plastic surgery, we highlight the absence

of weight reduction and weight stability.

There are little data regarding the response of services that offer reduction gastroplasty

in the face of these concerns. Therefore, this study may bring more data to the scientific

community to understand and direct actions in the face of the challenge of managing

these patients since they will increasingly integrate into society.

OBJECTIVE

To assess the prevalence of body contouring surgery performed between 2015 and 2018,

in patients previously submitted to bariatric surgery between 2014 and 2015, with

both procedures respectively performed by the specialist teams of Plastic Surgery

and Digestive Surgery at Hospital de Clínicas from the State University of Campinas

(HC-UNICAMP), in the city of Campinas, São Paulo.

METHODS

Observational, retrospective study that measured the prevalence of patients undergoing

body contouring surgery, which took place between 2015 and 2018, after having previously

undergone bariatric surgery between 2014 and 2015 at HC-UNICAMP. These are bariatric

and plastic surgeries performed by the Digestive Surgery and Plastic Surgery teams

at HC-UNICAMP, respectively, duly monitored and recorded by the researchers.

In order to find which patients underwent bariatric surgery between 2014 and 2015,

a triple check was performed. First, through their own records stored by the multidisciplinary

team of Bariatric Surgery, then through the HC-UNICAMP information system, and finally,

through the review of medical records.

Once the patients who met the criteria mentioned above were identified, a double check

was carried out; the first in the information system of the University Hospital, in

order to assess how many of these patients, previously submitted to obesity surgery,

were also submitted to reconstructive plastic surgery, while the second investigation

was carried out by checking their medical records.

Regarding the data collected in the medical records, the following variables were

chosen for analysis: gender, bariatric surgery technique used, body mass index (BMI)

at the time the bariatric surgery was performed, BMI on the date of indication of

the body contouring surgery, modality of body contouring surgery used, age on the

day of the plastic surgery, the time between the obesity surgery and the surgery performed

by the Plastic team.

Patients who underwent body contouring surgery between 2015 and 2018, after bariatric

surgery between 2014 and 2015, by the Plastic Surgery and Digestive System Surgery

team at HC-UNICAMP were included in this study. We excluded patients who had not undergone

both reduction gastroplasty and body contouring surgery at the HC-UNICAMP, those who

did not have medical records located, those who underwent the aforementioned surgical

procedures in other years, patients with incomplete records, as well as those who

refused to sign the Free and Informed Consent Term (FICT).

Participants who proposed to participate in the study signed the informed consent

and received a copy. During all stages of the investigation, the researchers treated

the identity of patients with professional standards of confidentiality, in compliance

with Brazilian legislation (Resolution No. 466/12 of the National Health Council),

using the information only for academic and scientific purposes. The medical team

was and remains available to resolve patients’ doubts regarding this research’s procedures.

Data analysis was performed by calculating percentages, means and medians using Microsoft© Office Excel.

Data collection for this research began after approval by the Research Ethics Committee

(CEP) of the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) under the number CAAE: 11081219.2.0000.5404.

RESULTS

A total of 208 bariatric surgeries were performed on 183 women and 25 men in 2014

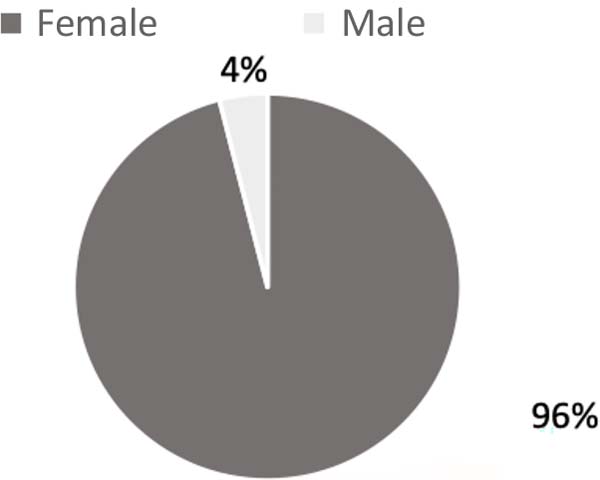

and 2015. Of these, 11% (n=23) underwent 27 body contouring surgeries (Table 1). Almost all plastic surgeries were performed on female patients (Figure 1). The mean age of patients undergoing body contouring surgery was 36 years, with

a median of 37 years, ranging from 22 to 53 years. The 23 patients who met the criteria

for this study had previously undergone Fobi-Capella surgery.

Table 1 - Body contouring surgeries performed between 2015 and 2018 by the Plastic Surgery team

at HC-UNICAMP in patients previously submitted to bariatric surgery at the same hospital.

| Surgery performed |

Frequency (%); n=27 |

| Abdominal dermolipectomy |

59 |

| Brachioplasty |

22 |

| Mammoplasty |

7 |

| Dorsoplasty |

7 |

| Cruroplasty |

4 |

Table 1 - Body contouring surgeries performed between 2015 and 2018 by the Plastic Surgery team

at HC-UNICAMP in patients previously submitted to bariatric surgery at the same hospital.

Figure 1 - Sex of patients undergoing body contouring surgery after bariatric surgery, between

2015 and 2018, by the Plastic Surgery team at HC-UNICAMP.

Figure 1 - Sex of patients undergoing body contouring surgery after bariatric surgery, between

2015 and 2018, by the Plastic Surgery team at HC-UNICAMP.

The mean BMI pre-gastroplasty was 36 kg/m2, while the BMI before the body contouring surgery was 23.6 kg/m2, with a mean delta BMI of 12.4 kg/m2. The time interval between bariatric surgery and reconstructive plastic surgery was

29 months in our sample. All patients undergoing body contouring surgery in this series

were discharged from the hospital on the first postoperative day (n=23).

The performance of more than one procedure for correcting body deformity occurred

in 13% (n=3) of the patients. One patient underwent anchor abdominoplasty and dorsoplasty

simultaneously. Another also had his abdomen operated on first and later underwent

dorsoplasty and mammoplasty, performed in the same surgical procedure. The third,

during follow-up, needed reduction mammaplasty after having been previously submitted

to abdominal dermolipectomy. Initially submitted to brachial dermolipectomy, one case

was followed up with an indication for rhytidoplasty and facial fat grafting; neither

procedure was included in the calculation of body contouring surgeries.

In the abdominal approaches, the anchor abdominoplasty technique was used with the

excision of the original umbilicus, the surgical specimen, and the neo umbilicus fabrication,

using bilateral skin-fat flaps.

DISCUSSION

Body contouring surgeries after significant weight loss help improve self-esteem and

reintegrate these patients into social and professional life, facilitating hygiene

and walking and improving sexual performance7. Surgical techniques vary according to each case and are difficult to perform due

to exuberant sagging, poor skin quality and loss of elasticity. Increased vessel caliber,

anemia and protein-calorie malnutrition increase the incidence of complications8.

The aesthetic results obtained in patients with morbid obesity are below those achieved

in non-obese patients. However, the relief from removing excess skin fat is greater

than the presence of scars, leading to improved quality of life7. The selection of patients is based on a detailed clinical history and physical examination,

which, combined with an accurate surgical technique, allow the achievement of satisfactory

aesthetic results and, above all, with a low rate of complications9.

The desire for surgeries to improve body contour after massive weight loss is a growing

demand. A study by Kitzinger et al.10 found that 75% of women and 68% of men were interested in plastic surgery after weight

loss. Although many patients wish to undergo body contouring surgery, unfortunately,

they do not have access to the surgical procedure, bringing several other consequences

to the SUS, such as occupancy of beds due to complications, and increased care costs,

among others.

In developing countries, such as Brazil, problems in the organization and hierarchy

of the health system and inequity in access to services make plastic surgery care

beyond the reach of a large portion of the population. In Rio de Janeiro, for example,

the average time for scheduled care for the population ranges from 30 days for physical

therapy consultations to 123 days for reconstructive plastic surgery, the latter being

the specialty with the longest waiting time, which corroborates our hypothesis of

difficult access11. A possible contributing factor may be the need for patients to travel large geographic

distances to the specialist, which makes it difficult to maintain a regular schedule

of follow-up consultations, in addition to creating barriers to establishing bonds

with the team and the service.

In our series, associations of procedures were avoided since, in addition to the complex

surgeries, the patients, formerly morbidly obese, often have comorbidities such as

arterial hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, among others, which could increase the

risks of complications.

The mean BMI before plastic surgery of 23.6 kg/m2 was lower than that found by other authors12-15. Likewise, the mean delta BMI of

our patients, 12.4 kg/m2, was below 18.3 kg/m2, 20.7 kg/m2, and 22.3 kg/m2 verified in other studies12,14,16. We believe that this finding is related to the preoperative follow-up by the multidisciplinary

team, which throughout the surgical planning, encourages changes in life habits, in

addition to improvements in eating habits, which is reversed in intense weight loss

even before surgery to obesity. This study’s most common plastic surgery was abdominal

dermolipectomy, also found in several other studies10,14,17,18.

Worldwide, there is a lack of data on the real rate of patients undergoing reconstructive

plastic surgery after a bariatric procedure19. Studies that analyze reconstructive plastic surgeries by the SUS are uncommon in

Brazil. In our country, between 2010 and 2016, there were 6,654 hospitalizations for

post-bariatric reconstructive plastic surgery via the public network. Only 14.5% of

patients who underwent bariatric surgery also had access to this care. Of this total

number of surgeries, 52% of the procedures corresponded to abdominal dermolipectomy,

17% to mammoplasty and 13% to brachial dermolipectomy, with a total expense of hospitalizations

for SUS related to reparative surgical procedures of R$ 6,019,082.72. Considering

that the same patient may have performed more than one procedure, this prevalence

should be even lower.17

These data corroborate our research findings, which measured the level of access to

restorative therapy at 11%. Furthermore, 93% of reconstructive plastic surgeries after

bariatric surgery were performed on female patients, a rate similar to that reported

by Rosa et al. in a study on the profile of post-bariatric patients undergoing plastic

surgery procedures in Brasília and at the percentage found in our study, 96%14,17. This number was slightly higher than that found in a study previously carried out

by the Plastic Surgery team at HC-UNICAMP, which reported 91% of the female population

in a retrospective analysis of post-bariatric abdominoplasties20.

Regarding the age of the patients at the time of the body contouring surgery, our

findings are similar to those reported by Aldaqal et al.18, in a study carried out in Saudi Arabia, who found a mean age of 37 years. This age

is lower than those published by a previous study by UNICAMP20, 40 years old, by the group by Rosa et al.14, 41 years old, and by Poyatos et al.16, in Barcelona, 48 years old. The average time interval between bariatric surgery

and reconstructive plastic surgery was 29 months in our series, which is lower than

the 42 months and 47 months seen in other national studies but higher than the 22

months and 24 months described in other works10,14-16.

Gusenoff et al.21 reported that 11.3% of 926 patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery underwent

follow-up plastic surgery in a study by the University of Rochester, USA. In the same

state of New York, another research group published that reconstructive plastic surgery

was performed by only 6% of patients after bariatric procedures19. Aldaqal et al.18, in Saudi Arabia, reported a slightly higher rate, 14%. Regarding Europe, Kitzinger

et al.10, in Austria, found that among patients who underwent bariatric surgery between 2003

and 2009, only 21% actually underwent body contouring surgery, while in Greece, a

prevalence of 3.6%22 is reported. Health insurance and income are associated with

the search for surgery, and improved access to health services can increase the number

of patients able to undergo these reconstructive procedures 19

Less than 10% of patients who undergo bariatric surgery through the public health

system will have access to body contouring surgery10,19. Public health systems that do not provide coverage for reconstructive plastic surgery

prevent most bariatric patients from accessing the procedures, as only a small part

of them have the financial resources to pay the particular costs of corrective procedures.

This may explain the low percentage of post-bariatric reconstructive plastic surgeries

described in the international literature. Other possible reasons for the low-performance

rate of reparative procedures are fear of complications in other surgeries and differences

in the quality of information on aspects of body contouring procedures18.

The SUS must act as an instrument for promoting citizenship for people who experience

massive weight loss. Promoting, therefore, comprehensive care and offering, in an

articulated and continuous way, the resources that make it possible to face the determinants

and conditions of health and illness of this type of patient.

CONCLUSION

There is an immense lack of this treatment, which irremediably compromises the functional

results and quality of life of patients undergoing bariatric surgery. Despite its

limitations due to its unicentric nature and small sample space, this study provides

initial evidence on the prevalence of body contouring procedures after bariatric surgery

in our country. Thus, we believe that more studies of this type should be carried

out in other referral centers to verify the real access to body contouring surgery

after bariatric surgery among SUS patients. Our findings may be used as indicators

to guide actions aimed at improving care for patients in the postoperative period

of Bariatric Surgery in Brazilian public hospitals.

REFERENCES

1. Dietz WH, Baur LA, Hall K, Puhl RM, Taveras EM, Uauy R, et al. Management of obesity:

improvement of health-care training and systems for prevention and care. Lancet. 2015;385(9986):2521-33.

2. Soldin M, Mughal M, Al-Hadithy N; Department of Health; British association of Plastic,

Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons; Royal College of Surgeons England. National

commissioning guidelines: body contouring surgery after massive weight loss. J Plast

Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014;67(8):1076-81.

3. Aldaqal SM, Makhdoum AM, Turki AM, Awan BA, Samargandi OA, Jamjom H. Post-bariatric

surgery satisfaction and body-contouring consideration after massive weight loss.

N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5(4):301-5.

4. Giordano S, Victorzon M, Koskivuo I, Suominen E. Physical discomfort due to redundant

skin in post-bariatric surgery patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(7):950-5.

5. Kitzinger HB, Cakl T, Wenger R, Hacker S, Aszmann OC, Karle B. Prospective study on

complications following a lower body lift after massive weight loss. J Plast Reconstr

Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(2):231-8.

6. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Portaria No 425, de 19 de março de 2013. Estabelece regulamento

técnico, normas e critérios para a Assistência de Alta Complexidade ao Indivíduo com

Obesidade. Brasília: Diário Oficial da União; 2013.

7. Cortes JES, Oliveira DP, Sperli A. Abdominoplastias em âncora em pacientes ex-obesos.

Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2009;24(1):57-63.

8. Gerk PO. Cirurgia do Contorno Corporal Após Grandes Perdas Ponderais. Rev Bras Cir

Plást. 2007;22(3):143-52.

9. Almeida EG, Almeida Júnior GL. Abdominoplastia: Estudo Retrospectivo. Rev Bras Cir

Plást. 2008;23(1):1-10.

10. Kitzinger HB, Abayev S, Pittermann A, Karle B, Kubiena H, Bohdjalian A, et al. The

prevalence of body contouring surgery after gastric bypass surgery. Obes Surg. 2012;22(1):8-12.

11. Pinto LF, Soranz D, Tomasi Scardua MT, Silva IM. A regulação municipal ambulatorial

de serviços do Sistema Único de Saúde no Rio de Janeiro: avanços, limites e desafios.

Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2017;22(4):1257-67.

12. Coon D, Michaels J 5th, Gusenoff JA, Purnell C, Friedman T, Rubin JP. Multiple procedures

and staging in the massive weight loss population. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(2):691-8.

13. Orpheu SC, Coltro PS, Scopel GP, Saito FL, Ferreira MC. Body contour surgery in the

massive weight loss patient: three year-experience in a secondary public hospital.

Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2009;55(4):427-33.

14. Rosa SC, Macedo JLS, Casulari LA, Canedo LR, Marques JVA. Anthropometric and clinical

profiles of post-bariatric patients submitted to procedures in plastic surgery. Rev

Col Bras Cir. 2018;45(2):e1613.

15. Donnabella A, Neffa L, Barros BB, Santos FP. Abdominoplasty after bariatric surgery:

experience in 315 cases. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2016;31(4):510-5.

16. Poyatos JV, Del Castillo JMB, Sales BO, Vidal AA. Post-bariatric surgery body contouring

treatment in the public health system: cost study and perception by patients. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(3):448-54.

17. Carvalho ADS. Cirurgias bariátricas realizadas pelo Sistema Único de Saúde-2010 a

2016: Uma Análise das Hospitalizações [dissertação]. Porto Alegre: Universidade Federal

do Rio Grande do Sul; 2018.

18. Aldaqal SM, Samargandi OA, El-Deek BS, Awan BA, Ashy AA, Kensarah AA. Prevalence and

desire for body contouring surgery in postbariatric patients in Saudi Arabia. N Am

J Med Sci. 2012;4(2):94-8.

19. Altieri MS, Yang J, Park J, Novikov D, Kang L, Spaniolas K, et al. Utilization of

Body Contouring Procedures Following Weight Loss Surgery: A Study of 37,806 Patients.

Obes Surg. 2017;27(11):2981-7.

20. Mizukami A, Ribeiro BB, Renó BA, Calaes IL, Calderoni DR, Basso RCF, et al. Análise

retrospectiva de pacientes pós-bariátrica submetidos à abdominoplastia com neo-onfaloplastia:

70 casos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;29(1):89-93.

21. Gusenoff JA, Messing S, O’Malley W, Langstein HN. Patterns of plastic surgical use

after gastric bypass: who can afford it and who will return for more. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 2008;122(3):951-8.

22. Sioka E, Tzovaras G, Katsogridaki G, Bakalis V, Bampalitsa S, Zachari E, et al. Desire

for Body Contouring Surgery After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy. Aesthetic Plast

Surg. 2015;39(6):978-84.

1. Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Departamento de Cirurgia, Área de Cirurgia Plástica

- Campinas - São Paulo - Brazil

Corresponding author: Luiz Henrique Zanata Pinheiro Cidade Universitária Zeferino Vaz, Barão Geraldo, Campinas, SP, Brasil. Zip code:

13083-970, E-mail: henriquez_pinheiro@hotmail.com

Article received: September 25, 2021.

Article accepted: December 13, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.