Original Article - Year 2022 - Volume 37 - Issue 4

Pyoderma gangrenosum: update and guidance

Pioderma gangrenoso: atualização e orientação

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) is a neutrophilic disease, rare but with a poor outcome. The Capitulum of Wound treatment of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (SBCP) promoted a discussion with the Brazilian societies of Dermatology and Rheumatology to extract the best procedures in diagnostic and treatment.

Methods: Broad review of published articles related to the subject and compilation of guidelines of diagnostic and treatment by two advisors of each involved society, plastic surgery, dermatology and rheumatology.

Results: The PG is not an exclusion disease anymore, with well defined criteria for its diagnostic and literature based treatment, refined by the authors, including the use of biological therapies.

Conclusion: The PG remains challenging, but systematizing the investigation and the use of new drugs has opened a new horizon of treatments, interfering in the pathophysiology in a positive manner with fewer side effects than immunosuppressive therapy alone.

Keywords: Pyoderma gangrenosum; Pyoderma; Skin diseases; Autoimmunity; Neutrophils; Societies, medical.

RESUMO

Introdução: O pioderma gangrenoso (PG) é uma doença neutrofílica, rara, porém de consequências danosas. O Capítulo de Feridas da Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP) foi instado a compilar as melhores práticas, tanto diagnósticas como terapêuticas, junto às Sociedades Brasileiras de Dermatologia e Reumatologia para um melhor esclarecimento dos seus membros.

Métodos: Ampla revisão de artigos publicados na literatura médica e compilação das novas diretrizes de diagnóstico e tratamento por dois membros indicados por cada uma das Sociedades Brasileiras de Cirurgia Plástica, Dermatologia e Reumatologia.

Resultados: O PG deixou de ser uma doença de exclusão, tendo os critérios diagnósticos bem definidos e a orientação terapêutica delineada pelos autores, incluindo o uso de terapia biológica.

Conclusão: O PG permanece desafiador, mas sistematizar a investigação e o uso dos novos medicamentos, bem como o manejo das feridas, abre novas perspectivas, interferindo na fisiopatologia de modo positivo, com maior precocidade e menos efeitos colaterais do que a terapia imunossupressora de forma isolada.

Palavras-chave: Pioderma gangrenoso; Pioderma; Dermatopatias; Autoimunidade; Neutrófilos; Sociedades médicas.

INTRODUCTION

Pyoderma gangrenosum and the spectrum of neutrophilic dermatoses

Pyoderma gangrenosum (PG) belongs to a group of conditions characterized by polymorphous skin manifestations that include pustules, blisters, abscesses, papules, nodules, plaques and ulcers, whose histopathological substrate shows intense inflammatory infiltrate with a predominance of neutrophils, being, therefore, called dermatoses neutrophils1. Due to the possible occurrence of extracutaneous manifestations and neutrophilic infiltration in different organs and systems, they would be more adequately defined as neutrophilic diseases2.

In addition to PG, neutrophilic diseases include acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis (Sweet’s syndrome), diurnal raised erythema, neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis, subcorneal pustular dermatosis, IgA pemphigus, amicrobial pustulosis of the folds, and Behçet’s disease, among others1,3. These diseases manifest in isolation, but it is not surprising that some of these conditions eventually occur concomitantly or sequentially, considering that they share the same inflammatory infiltrate and are usually associated with the same systemic diseases4.

There is also a possible association with several systemic conditions, such as inflammatory bowel diseases, hematological diseases, rheumatological diseases, upper airway and gastrointestinal tract infections, and drug reactions. Neutrophilic diseases share clinical and anatomopathological peculiarities with the so-called autoinflammatory diseases, characterized by recurrent episodes of inflammation in affected organs in the absence of infection, allergy or autoimmunity1,3.

Pathergy

The phenomenon of pathergy refers to a condition of exaggerated tissue reactivity that occurs in response to minimal trauma and leads to the appearance of new lesions or the worsening of previous lesions. It is most commonly seen in pyoderma gangrenosum and occasionally in Sweet’s syndrome. Generally, pathergy is provoked by biopsies, injections, venipunctures, vascular access, surgical debridement and various surgeries, but minor trauma caused by abrasions, insect bites, and removal of skin adhesives can also trigger pathergy reactions5.

This phenomenon is also observed and used in diagnosing Behçet’s disease through skin injury caused by a needle, the so-called pathergy test6.

Although the precise mechanism of this phenomenon is not known, it is assumed that the abnormal inflammatory response triggered by tissue injury is due to the exaggerated release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines by keratinocytes and other cells present in the epidermis and dermis, resulting in the intense perivascular inflammatory infiltrate of polymorphonuclear cells, observed on histopathological examination7.

Epidemiology

PG is rare, with an estimated prevalence of 58 cases/1 million adults in the US population, and an incidence of 6.3 cases/1 million individuals/year, according to a British study8,9.

The disease is even rarer in children, affecting mainly individuals around 50 years of age, with a slight predominance of females, with an average age of 44.6 years (±19.7) of onset of the disease10,11.

Mortality is also higher in PG patients, with a risk three times higher compared to age-matched controls9. However, studies are lacking in understanding why this increased mortality and how much it could be attributed to associated comorbidities, immunosuppression, infections and iatrogenic events12.

A survey carried out in Germany with specialists in wound care, which included 31,619 patients with chronic leg ulcers, showed that PG accounted for 3% of all cases13.

Clinical condition

The classic and predominant form of PG begins with an erythematous papule or pustule that evolves into a painful ulceration that progresses rapidly, with typical characteristics of detached violaceous edges and surrounding erythema. The ulcer can reach large dimensions and go deep into the subcutaneous tissue, less frequently reaching the fascia and exposing muscles and tendons. The ulcer bed may be exudative, purulent, necrotic, or show exuberant granulation tissue. Ulcers usually appear in areas of trauma, more frequently on the lower limbs, are solitary or multiple, may converge, and tend to resolve with atrophic scars type “cigarette paper” or cribriform type.

The classic form of PG may be associated with inflammatory bowel disease, hematological malignancies, inflammatory arthropathies and monoclonal gammopathies. The syndromic types of PG related to autoinflammatory diseases also manifest with the ulcerative form of the disease14-16. In addition to the classic presentation of PG, we have other forms that are necessary to know (Chart 1 and Figures 1 and 2)1.

| Variant | Clinical presentation | Common locations | Associated systemic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ulcerative | Inflammatory pustules or nodules that rapidly progress to necrotic ulcers with violaceous undermining edges with surrounding erythema | Trauma sites | Inflammatory bowel disease Hematologic maligna Rheumatoid arthritis Seronegative arthritis Monoclonal gammopathy |

| Anterior face of lower limbs | |||

| Bullous | Painful blister that can progress to erosion and/or a rapidly evolving ulcer | Face | ex. Acute myeloid leukemia, inflammatory bowel disease |

| Upper and lower limbs | |||

| Pustular | Pustules with erythematous edges and Symmetrical | Lower members | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| Trunk | |||

| Vegetative | Less painful variant | Trunk | None |

| Slow growth | |||

| No purulent | |||

| Single superficial ulcer, non-subminated and less violaceous borders | |||

| Respond quickly to therapy | |||

| Peristomal | Papules that evolve into ulcers with subminated borders | Immediately adjacent to the stoma | Enteric malignancy |

| Difficult to distinguish from other peristomal erosive lesions | Connective tissue disease Monoclonal gammopathy | ||

| Postoperative | Erythema at the surgical site followed by dehiscence ulcer OR ulcerations that coalesce | Surgical site | Commonly associated with chest and abdomen surgery |

| Disproportionately increased pain |

PAPA - pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne; PAPASH - pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne and hidradenitis suppurativa; PASH - pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, hidradenitis suppurativa; PG - Pyoderma gangrenosum; SAPHO - synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis; PASS - pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobata, suppurative hidradenitis e axial spondyloarthritis; PsAPASH - pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, suppurative hidradenitis e psoriatic arthritis.

PG can evolve with an abrupt onset and rapid progression of the lesions, when it usually presents with intense pain and general manifestations of fever, adynamia, myalgia and arthralgia, or follow an indolent course, with gradual progression of the lesions, usually without presenting general manifestations. Lymphangitis and lymphadenitis are usually not present17.

Rarely, some patients may have extracutaneous neutrophilic infiltration, either asymptomatic or accompanied by clinical manifestations, depending on the organ affected. It may occur in patients with hematological, intestinal, or rheumatic comorbidities and those without associated systemic disease. Extracutaneous manifestations are more common in the lungs and eyes, less common in the kidneys, spleen and bones, and rarer in muscles, mucous membranes (buccal, tongue, pharynx, larynx and genitalia)4, the central nervous system, the cardiovascular system and in the gastrointestinal tract18.

Clinical associations

Systemic diseases are frequently observed in patients with PG, but the frequency is quite variable in the different series published in the literature (33-78%)9,11,19-21. In a systematic review of the literature and a multicenter study that evaluated a large number of patients with PG, the main systemic diseases associated with PG were inflammatory bowel disease, inflammatory arthropathies, solid tumors, and malignant and non-malignant hematological diseases (Chart 2)21,22. In a large study that evaluated PG in 56,097 patients with inflammatory bowel disease, the frequency of PG was 0.5%, and this manifestation was more frequently associated with Crohn’s disease compared to ulcerative colitis23. PG may occur concomitantly with the diagnosis of the systemic disease, or it may occur independently of the activity of the associated disease24.

| Groups | Frequency | Illnesses |

|---|---|---|

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 41.0% | Crohn’s disease |

| Ulcerative colitis | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Inflammatory arthropathies | 20.5% | Enteropathy |

| Arthropathy | ||

| Psoriatic arthritis | ||

| Ankylosing spondylitis | ||

| Hematologic neoplasms | 5.9% | Arthritis unspecified |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | ||

| Acute myeloid leukemia | ||

| Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia | ||

| Non-malignant hematologic diseases | 4.8% | Large granular cell |

| lymphocytic leukemia | ||

| Myelofibrosis | ||

| Myelodysplastic syndrome monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined origin | ||

| Polycythemia vera | ||

| Solid organ neoplasms | 6.5% | -- |

PG can also occur as a manifestation of different autoinflammatory syndromes, also referred to as syndromes related to neutrophilic dermatitis. These monogenic autoinflammatory syndromes present PG as part of their clinical manifestations. Also, variants in classically autoinflammatory genes are observed in patients with neutrophilic dermatitis, which draws attention to this clinical manifestation as part of the spectrum of polygenic autoinflammatory conditions16. Chart 3 describes the main autoinflammatory syndromes associated with PG manifestations, clinical manifestations, and related genes. In most syndromes, there is a mutation in the PSTPIP1 gene that encodes the CD2-binding protein, which leads to less inhibition of the inflammasome, with greater production of IL-1 and IL-18 and neutrophilic activation25. The association with PG is seen in two other syndromes: the PASS syndrome (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne conglobata, hidradenitis suppurativa and axial spondyloarthritis) and the PsAPASH syndrome (pyoderma gangrenosum, acne, hidradenitis suppurativa and psoriatic arthritis), but there are no known genetic variants in association26.

| Autoinflammatory syndromes | Main clinical manifestations | Genes |

|---|---|---|

| PAPA syndrome | PG, acne and sterile pyogenic arthritis | PSTPIP1 |

| PASH syndrome | PG, acne and hidradenitis suppurativa | MEFV, NOD2, NLRP3, PSMB8, NCSTN |

| PAPASH syndrome | Pyogenic arthritis, PG, acne hidradenitis suppurativa | PSTPIP1, IL1RN, MEFV |

| SAPHO syndrome | Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis and osteitis | PSTPIP2, LPIN2, NOD2 |

| PASS syndrome | Espondiloartrite axial, PG, acne conglobata e hidradenite supurativa | -- |

| PsAPASH syndrome | Psoriatic arthritis, PG, hidradenitis suppurativa and acne | -- |

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PG is challenging and considered a diagnosis of exclusion since there are no specific clinical aspects and laboratory markers of the disease. Therefore, all differential diagnoses, in principle, should be systematically ruled out. The spectrum of conditions that deserve to be distinguished from PG is wide, which reinforces the complexity of its diagnosis and justifies the high frequency of diagnostic delays and errors, generally exposing patients to risks related to treatments14,25,27.

Chart 4 lists the main differential diagnoses of PG, especially the classic form. The bullous form must be differentiated, particularly from autoimmune bullous dermatoses, erythema multiforme and dyshidrosiform dermatitis, while the pustular form deserves distinction, essentially, from bacterial pyoderma, pustular psoriasis, subcorneal pustular dermatosis and pustular eruptions caused by drugs.

| Infections | |

|---|---|

| Viral (chronic herpes simplex, cytomegalovirus) | |

| Bacterial (ecthyma, gangrenous ecthyma, tuberculosis, atypical mycobacteriosis, necrotizing fasciitis) | |

| Parasitic (amebiasis, cutaneous leishmaniasis) | |

| Fungal (sporotrichosis, paracoccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, aspergillosis) | |

| Vasculitis and vasculopathies | |

| Behcet’s disease | |

| Cutaneous and systemic vasculitis (leukocytoclastic vasculitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, polyarteritis nodosa) | |

| Livedoid vasculopathy | |

| Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome | |

| Collagen diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis) | |

| Occlusive vascular disease and venous disease | |

| Venous ulcer | |

| Hypertensive ulcer | |

| Sickle cell disease ulcer | |

| Peripheral arterial obstructive disease | |

| Trophic ulcers(neuropathic) | |

| Neoplasms | |

| Cutaneous leucemia | |

| Cutaneouslymphomas | |

| Basal cell carcinoma | |

| Squamous cell carcinomas | |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Factitious dermatitis | |

| Injuries from injecting illicit drugs | |

| Halogenoderma | |

| Loxoscelism | |

| Calciphylaxis | |

Historically considered a diagnosis of exclusion, it would imply that all possible causes of cutaneous ulcers should be ruled out before confirming the diagnosis of PG, an impracticable and costly strategy today16. In order to resolve this impasse, proposals for the validation of diagnostic instruments have emerged to refine diagnostic accuracy. In 2004, Su et al.28 were the first to propose diagnostic criteria guide for PG, which maintains the requirement of excluding other causes of skin ulceration.

A more complete diagnostic instrument, proposed by an international panel of specialists, resulted from a consensus using the Delphi method and is shown in Chart 5. This instrument also scores the criteria classified into four categories (histology, history, clinical examination and therapeutic response), and it guaranteed a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 90%. It could serve as a diagnostic guide for clinicians to reduce diagnostic errors and improve the selection of patients for clinical trials29.

| Major criterion |

|---|

| Ulcer edge biopsy showing neutrophilic infiltrate |

| Minor criteria |

| Histology |

| Infection exclusion (special stains and tissue cultures) |

| History |

| Pathergy (occurrence of ulcers at sites of trauma) |

| Personal history of inflammatory bowel disease or inflammatory arthritis History of a papule, pustule, or vesicle rapidly progressing to ulceration |

| Physical examination (or photographic record) |

| Peripheral erythema, detached edge, hypersensitivity at the site of ulceration, Multiple ulcers (at least one in the anterior region of the leg) |

| Cribriform or “wrinkled-paper” scar after ulcer resolution |

| Treatment |

| Reduction in ulcer size after one month of immunosuppressive treatment |

Diagnosis of PG = major criteria + 4 minor criteria

* Proposed by consensus with the Delphi method (Maverakis et al.29).

Laboratory evaluation

The first step in the face of a suspected case of PG is to perform a deep incisional biopsy of the edge of the ulcer, including the adipose tissue. If this is not possible, a 4mm punch should be used for the biopsy. The sample taken must be divided into two fragments, one intended to execute cultures for bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi and the other fixed in formalin for histological processing. In addition to hematoxylin-eosin, special stains for bacteria, mycobacteria, fungi and protozoa, such as Gram, Fite, PAS and Giemsa, or corresponding ones, should be performed30.

Histopathological findings are not diagnostic; however, in addition to helping to exclude differential diagnoses of PG, they are usually very suggestive, showing edema, and intense neutrophil infiltration, with the formation of microabscesses, hemorrhage and necrosis in the dermis, which can extend to the hypodermis, usually without the presence of vasculitis and leukocytoclasia. Specific stains for microorganisms are PG15 negative.

Although there is no standardized guideline for laboratory evaluation of suspected cases of PG, a series of preliminary tests can be recommended to rule out potential differential diagnoses and investigate the presence of possible associated conditions. Blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, liver function, kidney function, electrophoresis of serum proteins, cryoglobulins, VDRL, autoantibodies (antinuclear, antineutrophil cytoplasmic, antiphospholipid), rheumatoid factor, routine urine and chest X-ray16.

Depending on any clinical manifestations associated with the suspected PG picture, the laboratory investigation should be extended with the request of specific tests, which may include vascular Doppler ultrasound, colonoscopy, radiographic images of affected joints, blood smear, myelogram, immunoelectrophoresis, coagulation tests, abdominal ultrasound and chest tomography, among others. Screening for malignant neoplasms is recommended according to the patient’s age, considering that PG can be a paraneoplastic manifestation12,30.

Treatment

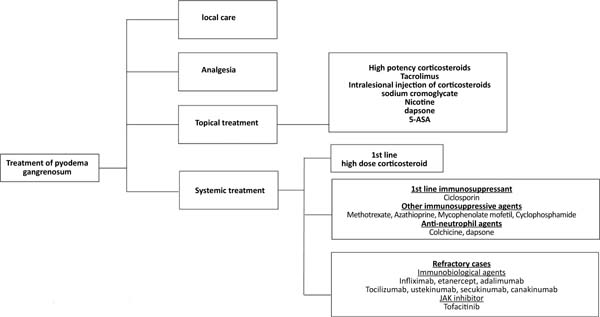

The treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum should be based on the characteristics of the lesion (location, number, size), extracutaneous manifestations, diseases associated with pyoderma, the presence of comorbidities25, and the severity of the condition31. It ranges from local care, analgesia, topical medications, systemic treatment, and immunosuppressive agents to immunobiological agents25,31,32 (Figure 3).

Topical treatment is indicated in cases of small lesions or localized pyoderma25,32 and can be performed with high-potency topical corticosteroids, intralesional injection in the active edges of the lesion, or tacrolimus25,31,32. Other options for topical use include sodium cromoglycate, nicotine, dapsone, and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA)25,31.

Systemic treatment should be reserved for the most severe cases and is performed with corticosteroids, at a dose of 0.5 to 1.0mg/kg/day of prednisolone or equivalent, as a first-line drug25,31. Intravenous pulse therapy with methylprednisolone (1g/day, 2 to 3 days)25 may be prescribed as a measure of rapid response, in association with immunosuppressants31, such as methotrexate (2.5-25mg/week)25, cyclophosphamide (0.5 -1.0g/day)25, azathioprine (50-100mg/2xs day)25, mycophenolate mofetil (1.0-1.5g/2xs day)25 or IV immunoglobulins (2.0-3.0g/kg)25.

Cyclosporine (2.5-5.0mg/kg/day)25 can be used alone or as a corticosteroid-sparing agent, especially in cases where there is a need for prolonged treatment31. Topical or systemic antibiotics and antineutrophil agents such as dapsone (100mg/day) and colchicine (0.5-1.0mg/day) may be beneficial. Antineutrophil agents have anti-inflammatory and prophylactic effects against Pneumocystis jiroveci infection32.

Several immunobiological agents have been proposed to treat PG, with anti-TNF alpha agents being the most studied32. Ben Abdallah et al.33, in a semi-systematic review of 222 articles, including 356 patients, demonstrated significant efficacy of these agents in adult individuals, with no statistically significant difference between infliximab, adalimumab or etanercept. The recommended doses are infliximab, 5mg/kg, EV25; adalimumab, 40mg every other week, SC25; etanercept, 50mg/week, SC34.

Other biologic therapy options include ustekinumab (anti-IL 12/IL23)25,35, secukinumab (anti-IL 17)35, canakinumab (anti-IL 1beta)25,35, anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist)25,35, tocilizumab (anti-IL-6 receptor)25,35, tofacitinib and ruxolitinib (ruxolitinib?) (JAK inhibitors)35, and apremilast (phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor)35.

Regarding the wound, surgical debridement is contraindicated as soon as the diagnostic hypothesis is formulated. Differentiation in the approach is crucial, as postoperative patients are almost always managed with a surgical site infection; with antibiotics and aggressive wound manipulation, inadequate therapy leads to worsening PG cases. Care must be centered on using chemical-biological dressings (calcium alginate, hydrogel, among others) with minimal manipulation, giving preference to long-lasting and non-adherent dressings. Routine skin care, such as hygiene, hydration and related to the prevention of pressure ulcers, should be redoubled.

Negative pressure therapy may be used, and hyperbaric oxygen therapy may be indicated for those who are intolerant or unresponsive to corticosteroid therapy. In patients with chronic wounds, a dermal matrix can and should be considered an alternative to promote wound closure.

CONCLUSION

Pyoderma gangrenosum remains a challenge both in its diagnosis and treatment. Diagnostic criteria are important tools to systematize the investigation in a logical and evidence-based manner. On the other hand, the use of biological drugs opened a new horizon of treatment, managing to interfere with the pathophysiology with better results and fewer side effects than immunosuppressive therapy alone.

REFERENCES

1. Marzano AV, Borghi A, Wallach D, Cugno M. A Comprehensive Review of Neutrophilic Diseases. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54(1):114-30.

2. Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. From acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis to neutrophilic disease: forty years of clinical research. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(6):1066-71.

3. Prat L, Bouaziz JD, Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD, Bagot M. Neutrophilic dermatoses as systemic diseases. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32(3):376-88.

4. Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses: a review of current treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10(5):301-12.

5. Varol A, Seifert O, Anderson CD. The skin pathergy test: innately useful? Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302(3):155-68.

6. Sequeira FF, Daryani D. The oral and skin pathergy test. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77(4):526-30.

7. Ergun T. Pathergy Phenomenon. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:639404.

8. Xu A, Balgobind A, Strunk A, Garg A, Alloo A. Prevalence estimates for pyoderma gangrenosum in the United States: An age- and sex-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(2):425-9.

9. Langan SM, Groves RW, Card TR, Gulliford MC. Incidence, mortality, and disease associations of pyoderma gangrenosum in the United Kingdom: a retrospective cohort study. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(9):2166-70.

10. Monari P, Moro R, Motolese A, Misciali C, Baraldi C, Fanti PA, et al. Epidemiology of pyoderma gangrenosum: Results from an Italian prospective multicentre study. Int Wound J. 2018;15(6):875-9.

11. Bennett ML, Jackson JM, Jorizzo JL, Fleischer AB Jr, White WL, Callen JP. Pyoderma gangrenosum. A comparison of typical and atypical forms with an emphasis on time to remission. Case review of 86 patients from 2 institutions. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000;79(1):37-46.

12. Gupta AS, Ortega-Loayza AG. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a too often overlooked facultative paraneoplastic disease. Ann Hematol. 2019;98(9):2247-8.

13. Körber A, Klode J, Al-Benna S, Wax C, Schadendorf D, Steinstraesser L, et al. Etiology of chronic leg ulcers in 31,619 patients in Germany analyzed by an expert survey. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2011;9(2):116-21.

14. Ahronowitz I, Harp J, Shinkai K. Etiology and management of pyoderma gangrenosum: a comprehensive review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2012;13(3):191-211.

15. Wallach D, Vignon-Pennamen MD. Pyoderma gangrenosum and Sweet syndrome: the prototypic neutrophilic dermatoses. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178(3):595-602.

16. Maverakis E, Marzano AV, Le ST, Callen JP, Brüggen MC, Guenova E, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6(1):81.

17. Ruocco E, Sangiuliano S, Gravina AG, Miranda A, Nicoletti G. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an updated review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23(9):1008-17.

18. Borda LJ, Wong LL, Marzano AV, Ortega-Loayza AG. Extracutaneous involvement of pyoderma gangrenosum. Arch Dermatol Res. 2019;311(6):425-34.

19. Binus AM, Qureshi AA, Li VW, Winterfield LS. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a retrospective review of patient characteristics, comorbidities and therapy in 103 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2011;165(6):1244-50. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10565.x

20. von den Driesch P. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a report of 44 cases with follow-up. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137(6):1000-5.

21. Ashchyan HJ, Butler DC, Nelson CA, Noe MH, Tsiaras WG, Lockwood SJ, et al. The Association of Age With Clinical Presentation and Comorbidities of Pyoderma Gangrenosum. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(4):409-13. DOI: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.5978

22. DeFilippis EM, Feldman SR, Huang WW. The genetics of pyoderma gangrenosum and implications for treatment: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(6):1487-97. DOI: 10.1111/bjd.13493

23. Card TR, Langan SM, Chu TP. Extra-Gastrointestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease May Be Less Common Than Previously Reported. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(9):2619-26. DOI: 10.1007/s10620-016-4195-1

24. Callen JP, Jackson JM. Pyoderma gangrenosum: an update. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2007;33(4):787-802, vi. DOI: 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.07.016

25. Alavi A, French LE, Davis MD, Brassard A, Kirsner RS. Pyoderma Gangrenosum: An Update on Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(3):355-72. DOI: 10.1007/s40257-017-0251-7

26. Saternus R, Schwingel J, Müller CSL, Vogt T, Reichrath J. Ancient friends, revisited: Systematic review and case report of pyoderma gangrenosum-associated autoinflammatory syndromes. J Transl Autoimmun. 2020;3:100071. DOI: 10.1016/j.jtauto.2020.100071

27. Weenig RH, Davis MD, Dahl PR, Su WP. Skin ulcers misdiagnosed as pyoderma gangrenosum. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(18):1412-8.

28. Su WP, Davis MD, Weenig RH, Powell FC, Perry HO. Pyoderma gangrenosum: clinicopathologic correlation and proposed diagnostic criteria. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43(11):790-800.

29. Maverakis E, Ma C, Shinkai K, Fiorentino D, Callen JP, Wollina U, et al. Diagnostic Criteria of Ulcerative Pyoderma Gangrenosum: A Delphi Consensus of International Experts. JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(4):461-6.

30. Jourabchi N, Lazarus GS. Pyoderma gangrenosum. In: Kang S, Amagai M, Bruckner AL, Enk AH, Margolis DJ, Mcmichael AJ, et al, eds. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology. 9th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2019. p. 605-16.

31. George C, Deroide F, Rustin M. Pyoderma gangrenosum - a guide to diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19(3):224-8.

32. Fletcher J, Alhusayen R, Alavi A. Recent advances in managing and understanding pyoderma gangrenosum. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-2092.

33. Ben Abdallah H, Fogh K, Bech R. Pyoderma gangrenosum and tumour necrosis factor alpha inhibitors: A semi-systematic review. Int Wound J. 2019;16(2):511-21.

34. Roy DB, Conte ET, Cohen DJ. The treatment of pyoderma gangrenosum using etanercept. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54(3 Suppl 2):S128-34.

35. Skopis M, Bag-Ozbek A. Pyoderma gangrenosum: a review of updates in diagnosis, pathophysiology and management. J. 2021;4(3):367-75.

1. Hospital Agamenon Magalhaes, Departamento de Cirurgia Plástica, Recife, PE, Brazil

2. Universidade Federal de São Paulo UNIFESP-EPM, Disciplina de Reumatologia, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil

3. Universidade Federal de Goiás Faculdade de Medicina Serviço de Reumatologia, Goiânia,

GO, Brazil

4. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Departamento de Dermatologia, Belo Horizonte,

MG, Brazil

5. Faculdade de Medicina de Jundiaí, Departamento de Dermatologia, Jundiaí, SP, Brazil

LFDFV Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Final approval of the manuscript, Conceptualization, Conception and design of the study, Project Management, Methodology, Writing - Review and Editing, Supervision.

CLAA Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Research.

JR Analysis and/or interpretation of data, Conception and design of the study, Research.

Corresponding author: Luiz Felipe Duarte Fernandes-Vieira Av. Boa Viagem, 296/1004, Pina, Recife, PE, Brazil, Zip Code: 51011-000, E-mail: luizfelipedfv@gmail.com

Article received: November 30, 2021.

Article accepted: April 7, 2022.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter