INTRODUCTION

Rhinoplasty remains one of the most common aesthetic procedures1. More recently, technological advances in

injectable products based on hyaluronic acid (HA) and refinements of application

techniques have allowed HA to reach the gold standard as a volumizing agent2. Nasal reshaping with HA is a fast and

simple procedure that does not involve distancing recovery activities while

providing results comparable to conventional rhinoplasty3. The most common applications have been the correction of

deformities of the tip, back, and columella4.

Indications for nasal filling include patients who want to “test” the result of

rhinoplasty, patients undergoing rhinoplasty who do not wish to further surgery

to review a residual deformity, patients who are not candidates for surgery, and

patients waiting for the appropriate time interval before undergoing a secondary

rhinoplasty5,6. The nose is the subunit of the face most

at risk for fillings after glabella. As the number of patients submitted to

fillings increases, so does the number of associated adverse effects.

OBJECTIVES

According to the authors ‘ experience, this study aims to demonstrate a safe

technique, highlighting the anatomical knowledge and problems involved in nasal

reshaping in a standard case report.

METHODS

The main techniques used for Nasal reshaping are bolus and retroinjection. For

safety, we strongly suggest that this procedure be preferably performed with

cannulas. We do not use needles to inject into the nose. Injections should be

performed deep in the musculoaponeurotic layers and suprapericondral and

supraperiostal layers to avoid injury or cannulation of the vessels (which are

subdermal in this region) providing natural results and with greater safety.

In secondary rhinoplasty, extreme caution should be taken. Unpredictable blood

vessel repositioning and a more tenuous blood supply in the operated nose may

increase the risk of ischemia, necrosis, and vascular embolism after filler

injection. Anatomical planes may have been violated or healed. The dermis may be

adhered to deep planes; besides, natural anastomoses between contralateral

vessels may no longer be present.

The amount of HA injected per patient is variable. On average, the total

quantities range from 0.6 to 2ml. The desired modifications are elevation of the

nasal tip, increased nasolabial angle, and correction of nasal dorsum

irregularity with nasal root repositioning. These modifications will be

described below:

- The first step is to photograph the patient. Frontal, lateral, and

caudocranial incidences are essential. Images should be standardized

to help evaluate results;

- The nose is one of the areas most colonized by bacteria. Extra care

in the antisepsis is mandatory for the safety of this procedure;

- Intraoral access is used to block the infraorbital nerve with 2%

lidocaine without epinephrine. This time, tiny additional anesthetic

buds using lidocaine with epinephrine are injected into the nasal

tip and nasolabial angle. Anesthetics with epinephrine help reduce

the risk of peri-cannula bleeding. Remember that there will be a

halo of pallor due to the vasoconstrictor;

- The cannulas should be long enough to reach from the tip to the

nasal root. In general, 50mm in length is a good measure. Our

preference is for the 22G 50mm cannulas;

- In a single step, with the entry point at the nasolabial angle (the

paramedian intake is better than the median, so the syringe does not

touch the chin), we start increasing the columella-labial angle. The

cannula is advanced along the subcutaneous plane to the nasal spine.

Then, the HA is injected slowly, carefully observing the filling of

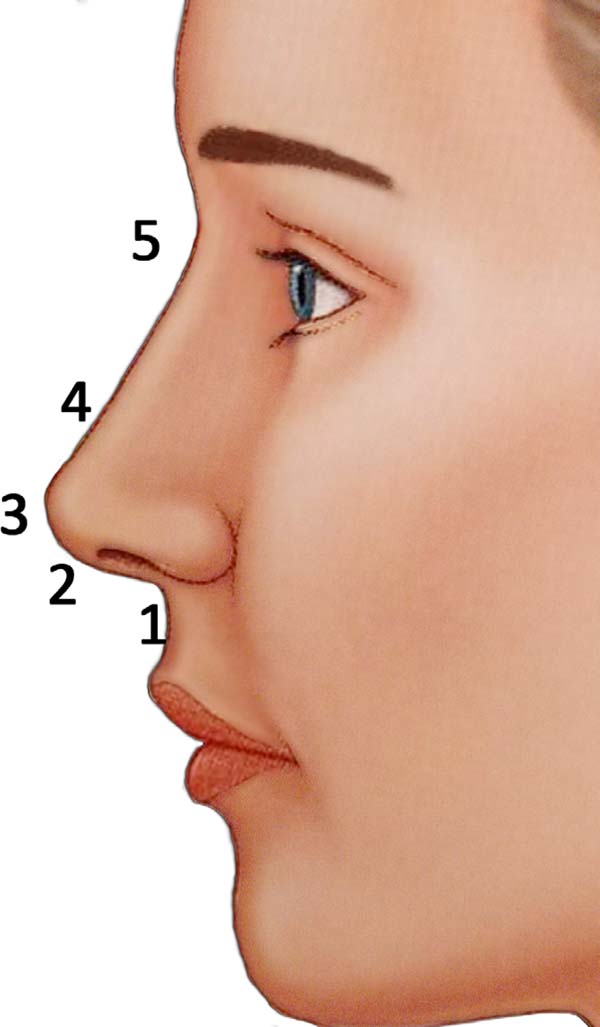

the columella-labial angle (Figure 1 - step 1);

Figure 1 - Sequential order of the fill. Edited figure: (Warren

RJ, Neligan P. Plastic surgery: aesthetics. 3rd ed.

Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. v. 2.).

Figure 1 - Sequential order of the fill. Edited figure: (Warren

RJ, Neligan P. Plastic surgery: aesthetics. 3rd ed.

Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015. v. 2.).

Once the nasolabial angle is corrected, the cannula is previously oriented to

strengthen and rectify the columella. This maneuver straightens, lengthens, and

supports the columella. This should produce a more anterior tip projection with

less cranial rotation. When stretching the columella, the nose should appear

more isosceles and the nostril more tear-shaped when viewed from the basal angle

(Figure 1 - step 2);

• In a single step, with the entry point still at the

nasolabial angle, the third stage begins with the tip’s projection.

A single bolus is sufficient for this purpose

(Figure 1 - step3(;

• The last step is to correct the back. Injections before and

after the comic can disguise it. Subsequent injection projects the

root. The final point is to create a new root at the approximate

level of the supratarsal fold, to create an angulation of

approximately 135 degrees of the nasal dorsum with the forehead, and

to create a new nasal profile, more aesthetically pleasing (Figure 1 - steps 4 and 5);

- Cohesive gels can be easily molded and remodeled to sculpt the

nose, such as “modeling mass” immediately after injection.

Additional syringes may be required at this stage;

- In all areas, always apply deep injections;

- In our technique, we start with the columella enhancement, then the

tip, and finish with the back;

- The right hand is used for smooth, measurable, and directional fill

injection. The left hand is used to guide placement, shaping, and

avoid inadvertent spreading of the injected load. This is

particularly important when injecting the dorsum since the lack of

accuracy of the injected filler creates a noticeable asymmetry;

- Slow and constant correction provides the safest way to achieve the

best results;

- Compression of the nasal and dorsal upper part of the angular

arteries is also recommended. It should always be injected more than

2 to 3 mm above the alar groove to avoid the lateral nasal

artery7;

- Stop injection immediately if there are ischemic changes in the

skin of the nose;

- Other additional fixes are always possible at a later date;

- Avoid large volumes of superficial injections as this can cause

external vascular compression, which can cause ischemia and necrosis

of the skin. This is especially important at the tip and nasal

base;

- Closely monitor the nose after the procedure for signs of ischemia,

particularly in those patients with a history of the previous

rhinoplasty, as their vascular supply may be distorted and

compromised;

- Avoid unnecessary external compression of the nose after injection,

such as wearing glasses, for at least a few days;

- A small dressing is added at the entry points at the end of the

procedure to avoid ha reflux and the consequent increased risk of

fistulization.

RESULTS

One of the authors developed this technique (Fernandes RL) in 2013, and since

then, it has been performed in approximately 60 patients. Results range from

good to very good in almost all patients. The duration of the effect of

correction of the dorsal gibbon is significant, with an average between 12 and

18 months. The duration of the tip lift is shorter, usually half that time. Pain

is considered mild to moderate using this technique. The most common side

effects are fistula (or HA vesicle) at the cannula’s entry points and persistent

erythema of the nose. No serious adverse events were observed using this

technique.

MCB, 28 years old, 1.2 ml HA (Teosyal Ultra Deep® - Teoxane Laboratory -

Genéve) with 22G cannula - 50mm (Figures 2,3 and 4).

Figure 2 - Results of the nasal reshaping procedure. A,

C and E pre-application.

B, D and F

post-application.

Figure 2 - Results of the nasal reshaping procedure. A,

C and E pre-application.

B, D and F

post-application.

Figure 3 - Pre-application HA. HA: Hyaluronic Acid.

Figure 3 - Pre-application HA. HA: Hyaluronic Acid.

Figure 4 - 3 weeks after the procedure.

Figure 4 - 3 weeks after the procedure.

DISCUSSION

Anatomy

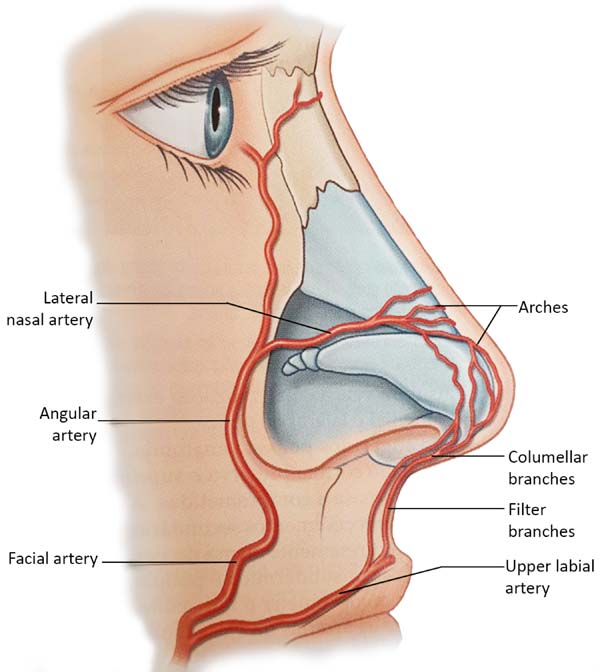

The extensive collateral blood supply of the nose makes this procedure

relatively safe. Both a branch of the internal carotid artery, the

supratroclear, and a branch of the external carotid artery, the facial

artery, give rise to branches that cross the midline. These form a vascular

network that runs through the back. Along the way, inferior to the nose, the

facial artery originates the upper labial artery, which also originates the

filter’s arteries, providing the ascending columellar arteries’ main

contribution. Several arches arise from both the supratroclear arteries and

the facial arteries (Figure 5); the

lateral nasal artery is one of the main sources of blood supply to the

nose.

Figure 5 - Arterial irrigation of the nose (Warren RJ, Neligan P.

Plastic surgery: aesthetics. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015.

v. 2.).

Figure 5 - Arterial irrigation of the nose (Warren RJ, Neligan P.

Plastic surgery: aesthetics. 3rd ed. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2015.

v. 2.).

Tansatit et al., in 20168, studied 50

cadaver noses and showed that the dorsal artery of the nose is not a

constant artery. It is present as a pair of arteries in 34%. The typical

pattern of the nose’s dorsal artery is a large and long artery that descends

through the back or side of the nose and is anastomosed with the lateral

nasal artery on one side or both. The lateral nasal artery (LNA) is a

constant branch of the alar groove’s facial artery. It represents an

anastomosis between the facial artery (FA) and ophthalmic artery (OA) in the

paracentral zone of the middle third of the face. In 28% of the cadavers, a

single and sizeable dorsal artery was presented8. The study used 57 adult hemifaces to allow precise

observation of the branches of the facial artery. Four patterns were

identified based on the detailed course and origin of the angular artery

(AA) concerning the surrounding structures. In type I, the persistent

pattern in which the AA traverses the LNA branch point toward the medial

corner area. In type II, the deviation pattern, the AA originates from FA

near the corner of the mouth and then heads towards the infraorbital area,

finally rotating medially along with the nasal areas nasojugal corner. This

pattern was the predominant type, and AA emerged along with the lower margin

of the eye’s orbicularis. In type III (alternative pattern), AA originates

from OA and runs down along the nose’s side. Finally, in type IV (latent

pattern), AF ends up as ALN without producing an AA branch. In summary, AA

originated from FA in 50.9% of the specimens dissected with persistent (type

I) and deviation (type II) patterns 8.

Venous drainage of the nose consists mainly of vessels anastomosed with the

facial vein, either through veins that travel from the back and lateral

nasal wall or through vessels that accompany the filter and upper labial

vessels8. The vascularization of

the nose is superficially located below the dermis.

Fillers

Fillers are volumizing biomaterials that are injected into dermal and/or

subcutaneous tissues for various reconstructive and cosmetic purposes,

especially on the face9. The use of

injectable fillers has skyrocketed in the last 25 years. The American

Society of Plastic Surgeons reports an increase from 650,000 filling

procedures in 2000 to 2.3 million in 20144. Hyaluronic acid (HA) injections comprise most of these

procedures (80%), followed by calcium hydroxyapatite (CaHA) (10%),

polylactic acid (5%), and autologous fat (3%)9.

From the 1990s to today, HA fillers have evolved technologically. They have

improved durability, versatility (gels with distinct rheological

characteristics and different tissue expansion capabilities), and safety.

These changes allowed HA to become a good volumizing agent10.

There is no identical or similar HA filler if we compare different brands.

The rheological characteristics of each product are unique. They differ

among the most diverse products, mainly depending on the following features:

being single-phase or biphasic, the molecular weight of its HA chains, the

technology and its degree of crosslinking, and the concentration of HA.

The main rheological parameters are viscosity, cohesiveness, and elasticity.

Viscosity is the spreading capacity of the gel. The more viscous, the

smaller the tissue spread. Surface applications require less viscous gels to

make results more natural without irregularities.

Cohesiveness is the resistance capacity of the gel to shear. The more

cohesive, the more united its structure remains when subjected to external

pressure. We give preference to the more cohesive HAs when we want to get

better-defined forms.

Elasticity is the ability to resist deformation when subjected to external

pressure. Deep planes are looser and require more elastic HAs for better

tissue expansion.

Of course, there is no ideal filler, but we recommend high viscosity,

cohesive, and elasticity HA if we want to perform a non-surgical rhinoplasty

effectively and safely. They are known as volumizers and are indicated for

subdermal application.

Adverse effects

The potential adverse events associated with filling are injection site

reaction, inappropriate injection (hypercorrection, nodulation, asymmetry),

product sensitivity, infection, and necrosis.

Although most complications are transient, some irreversible ones can cause

severe functional and aesthetic deficits1. Complications, fortunately, are not typical and range from

hematomas, edemas, and late granulomatous reactions to more severe skin

necrosis11,12. Necrosis of the nose’s tip’s skin

is particularly worrisome in the procedure, as it inevitably leads to

permanent disfigurement. However, the nasal dorsum correction without

considering the tip’s correction does not produce a comprehensive aesthetic

improvement.

Inadvertent injection of intravascular filler would lead to irreversible

necrosis of the skin. If an artery compression causes ischemia, it can

eventually be reversed by dissolving the filling of AH13,14. Due to this reason, in case of use of needles, we recommend the

filling injection only after the aspiration test, and we recommend that you

observe closely immediately after rhinoplasty with HA and be ready to inject

hyaluronidase.

Intermittent swelling followed by the development of palpable and/or painful

nodular papulocystic lesions, from weeks to months after the injection, can

progress to aseptic abscesses, the most common evolution being drainage

through a fistula. These reactions usually occur after patients have their

second or third injection. The histopathological analysis may show

non-granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate (chronic suppurative inflammatory

process with eosinophilia) or granulomatous reactions.

The mechanisms underlying the activation of the immune system and leading to

chronic granuloma formation are still unclear. Various agents, including

biomaterials, can trigger granulomatous reactions. These late reactions

related to HA fillers are immunological in nature, but an infectious origin

cannot be ruled out. It is important to differentiate two possible bacterial

presence sources: 1 - bacteria are directly inoculated in the filling

material or reach the filler from distant locations; 2 - systemic or remote

infection can provoke inflammatory immunomediator reactions harmful to

fillers in the absence of bacterial colonies in the filler. Clinically, a

nodule of consistency and late-onset may suggest a granulomatous response.

However, granuloma is a pathological diagnosis. True granuloma appears late

(especially after 6 to 24 months) at all injected sites at approximately the

same time; they grow quite fast.

The initial adverse effects described above tend to disappear within one or

two weeks spontaneously with symptomatic treatment. In cases of severe or

persistent swelling requiring corticosteroid use, betamethasone

(0.05mg/kg/day) is preferable due to its higher mineralocorticoid action

(antiedema) compared to the others.

Persistent hypercorrection can be treated early by incision and drainage. A

blade is inserted directed to the nodule, and an expression is

performed.

Hypersensitivity reactions usually regress without sequelae with the triple

therapeutic regimen: hyaluronidase injection (once a week while the reaction

persists) + antibiotics (macrolides such as clarithromycin or lymphomycins

such as clindamycin) for 14 to 21 days + oral prednisolone (0.5mg/kg/day,

while the reaction persists).

Due to frequent recurrence, corticosteroid treatment can last a long time.

All precautions related to corticosteroid side effects should be taken:

chest X-ray, bone densitometry, serum lipid dosage, blood pressure, and

blood glucose monitoring should be considered. For treatment for more than

three months, ophthalmological evaluation and supplementation of calcium

carbonate (1.5g per day) and sodium alendronate (70mg per week) is

recommended.

True granuloma usually reacts well to intralesional steroid injections

(triamcinolone acetonide), despite or associated with oral corticosteroid

ingestion.

The concomitance of HA reactions and other infectious conditions nearby is

quite common. Investigation of periodontal disease and chronic sinusitis

should be encouraged, especially in suggestive signs and symptoms.

The possibility of intravascular injection blindness is described in the

literature, but cases with HA showed better results than other fillers due

to hyaluronidase use, according to a meta-analysis study15. Another meta-analysis analyzed the

cases described and found that most were unilateral cases with acute visual

symptoms and signs, with a better prognosis in patients with partial loss of

vision and cases of anterior artery branch obstruction, with a worse

prognosis of complete blindness and obstructions in the central retinal

artery or ophthalmic artery16. In

arterial embolization cases, the immediate application of hyaluronidase and

the emergency evaluation of a specialist in angiology and vascular surgery

(possibly also an ophthalmologist qualified for retrobulbar injection) is

the best way to minimize sequelae.

CONCLUSION

We are in the midst of a new era of rhinoplasty, in which surgery is not the only

means to treat heart defects17.

Non-surgical options seem more feasible than they would be before the advent of

the new synthetic fillers18. In the

literature, however, there are few prospective studies focused on the efficacy,

safety, and longevity of HA fillers to support their usefulness as a

non-surgical alternative to rhinoplasty. Several rhinoplasty surgeons have used

fillers in the nose for many years, recognizing that HA can accurately smooth

irregularities and asymmetries in the nose after aesthetic rhinoplasty. Indeed,

the ability to smooth irregularities and asymmetries in the nose with an

injectable material still has great appeal because imperfections after

rhinoplasty are common.

The main advantage of using fillers in the nose is correcting a deformity without

the financial cost, anesthetic risk, or downtime usually associated with

surgical intervention. Disadvantages include potential damage to the nasal skin

envelope, the need for serial treatments to maintain correction, and a decrease

in the surgeon’s impulse to achieve the perfect intraoperative outcome5. Fear of occlusion or vascular compression

is undoubtedly the most threatening. However, we believe that by following the

simple steps of safety and having refined anatomical knowledge, fillers can be a

good tool for a safe and comprehensive improvement of modeling rhinoplasty.

REFERENCES

1. Robati RM, Moeineddin F, Almasi-Nasrabadi M. The risk of skin

necrosis following hyaluronic acid filler injection in patients with a history

of cosmetic rhinoplasty. Aesthet Surg J. 2018 Jan;38(8):883-8.

2. Fernandes RL. Hyaluronic acid filler for the malar area. In: Issa

MCA, Tamura B, eds. Botulinum toxins, fillers and related substances. Cham:

Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 271-80.

3. Youn SH, Seo KK. Filler rhinoplasty evaluated by anthropometric

analysis. Am Soc Dermatol Surg. 2016 Ago;42(9):1071-81.

4. Thomas WW, Bucky L, Friedman O. Injectables in the nose. Facial

Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2016 Ago;24(3):379-89.

5. Humphrey CD, Arkins JP, Dayan SH. Soft tissue fillers in the nose.

Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29(6):477-84.

6. Kurkjian TJ, Ahmad J, Rohrich RD. Soft-tissue fillers in

rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014 Fev;133(2):121-6.

7. Scheuer JF, Sieber DA, Pezeshk RA, Gassman AA, Campbell CF, Rohrich

RJ. Facial danger zones: techniques to maximize safety during soft-tissue filler

injections. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Mai;139(5):1103-8.

8. Tansatit T, Apinuntrum P, Phetudom T. Facing the worst risk:

confronting the dorsal nasal artery, implication for non-surgical procedures of

nasal augmentation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2017 Fev;41(1):191-8.

9. Wang LL, Friedman O. Update on injectables in the nose. Curr Opin

Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 Ago;25(4):307-13.

10. Williams LCBA, Kidwai S, Mehta K, Kamel G, Tepper O, Rosenberg J.

Nonsurgical rhinoplasty: a systematic review of technique, outcomes, and

complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020 Jul;146(1):41-51. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000006892

11. Johnson ON, Kontis TC. Nonsurgical rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg.

2016;32(5):500-6. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1586209

12. Alam M, Dover JS. Management of complications and sequelae with

temporary injectable fillers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007 Nov;120(6 Suppl

1):98S-105S.

13. Daher JC, Silva SV, Campos AC, Dias RCS, Damasio AA, Costa RSC.

Complicações vasculares dos preenchimentos faciais com ácido hialurônico:

confecção de protocolo de prevenção e tratamento. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2020;35(1):2-7.

14. Moon HJ. Use of fillers in rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2016

Jan;43(1):307-17.

15. Chatrath V, Banerjee PS, Goodman GJ, Rahman E. Soft-tissue

filler-associated blindness: a systematic review of case reports and case

series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2019 Abr;7(4):e2173.

16. Kapoor KM, Kapoor P, Heydenrych I, Bertossi D. Vision loss

associated with hyaluronic acid fillers: a systematic review of literature.

Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2020 Dez;44(3):929-44. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-019-01562-8

17. Ramos RM, Bolivar HE, Piccinini PS, Sucupira E. Rinomodelação ou

rinoplastia não-cirúrgica: uma abordagem segura e reprodutível. Rev Bras Cir

Plást. 2019;34(4):576-81.

18. Jasin ME. Nonsurgical rhinoplasty using dermal fillers. Facial Plast

Surg Clin North Am. 2013 Mai;21(2):241-52.

1. Institute of Plastic Surgery Santa Cruz,

São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: André Campoli Frisina, Rua Bento de

Andrade, 216, Jardim Paulista, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 04503-000.

E-mail: andrefrisina@yahoo.com.br

Article received: April 18, 2020.

Article accepted: April 18, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none