INTRODUCTION

The clandestine injection of industrial liquid silicone to modify body contour became

popular around 70 years ago when industrial-grade silicone was developed during World

War II for military purposes1-3.

Since the publication of Andrews et al., in 19894, showing for the first time the local and systemic complications of liquid silicone

in humans, this type of material has had its use contraindicated by the Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) and the former Medicines Division (DIMED) in Brazil4,5.

Currently, the majority of victims are women and transsexuals from countries in Asia

and South America. Due to the lack of resources for plastic surgery, they end up using

unqualified professionals1-3. Despite the prohibitions, the use of industrial silicone for aesthetic purposes

continues to be done alone or in association with other products, leading to severe

and potentially fatal complications1,6.

OBJECTIVE

To report a case of death after injection of industrial silicone in the buttocks and

thighs in a transsexual patient.

CASE REPORT

In this study, we report a healthy transsexual female patient, 24 years old, presenting

an injection of 3000ml of industrial liquid silicone in the buttocks and anterolateral

thighs. This procedure was performed in a home environment by a non-qualified professional.

After five days, she started showing signs of inflammation and epidermolysis at the

infiltration site, being submitted to superficial debridement at a medical service

near her residence. Due to a worsening of her general condition, she then sought the

emergency room at the Hospital das Clínicas of the University of São Paulo.

Upon admission, she already had extensive necrosis in the glutes and lateral region

of the hip associated with signs of septic shock, requiring orotracheal intubation

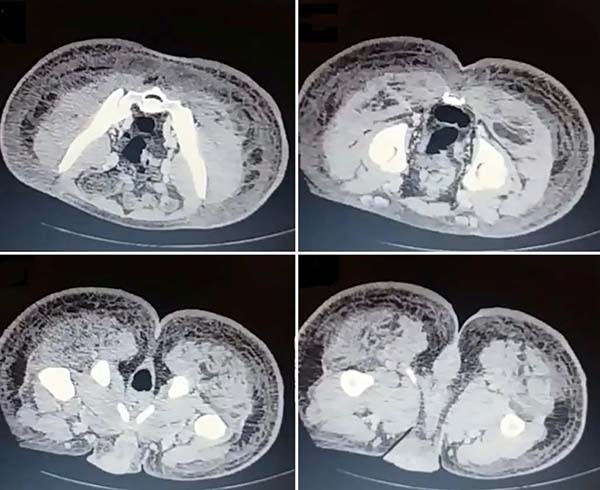

and the use of vasoactive drugs. Imaging exams showed diffuse densification with liquid

laminae pervaded, more pronounced in the lumbar, sacral, buttocks, and thigh roots

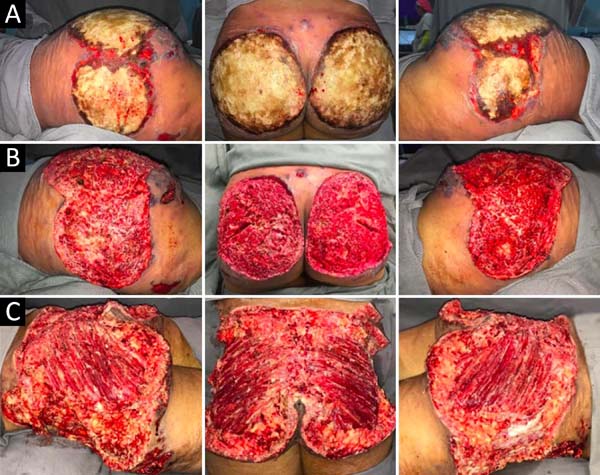

(Figure 1). The patient underwent six sequential surgical procedures for extensive debridement

of devitalized tissues, with identification of purulent collections and viscous substance,

compatible with silicone (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Initially, negative pressure therapy was used. After the second debridement, it

was replaced by a simple dressing with 1% silver sulfadiazine and cerium nitrate.

Cultures guided antibiotic therapy.

Figure 1 - Computed tomography of the pelvis and lower limbs showing diffuse local densification

with liquid laminae, more accentuated in the lumbar, sacral, gluteal regions, and

roots of the thighs.

Figure 1 - Computed tomography of the pelvis and lower limbs showing diffuse local densification

with liquid laminae, more accentuated in the lumbar, sacral, gluteal regions, and

roots of the thighs.

Figure 2 - Evolution of the wound after serial debridement; Right lateral; A. 6 days of evolution; B. After first debridement; C. After second debridement, with extension of the area of necrosis to the dorsal region

and lateral and anterior aspect of the thighs.

Figure 2 - Evolution of the wound after serial debridement; Right lateral; A. 6 days of evolution; B. After first debridement; C. After second debridement, with extension of the area of necrosis to the dorsal region

and lateral and anterior aspect of the thighs.

Figure 3 - Evolution of the wound after serial debridement; A. After the fourth debridement, exposure of the bilateral maximum gluteal muscle, B. After the fifth debridement, using a dressing with 1% silver sulfadiazine + cerium

nitrate.

Figure 3 - Evolution of the wound after serial debridement; A. After the fourth debridement, exposure of the bilateral maximum gluteal muscle, B. After the fifth debridement, using a dressing with 1% silver sulfadiazine + cerium

nitrate.

Figure 4 - Evolution of the wound after serial debridement; A. After the fourth debridement, with extension to the lateral and anterior aspect of

the thighs, B. After the fifth debridement, using a dressing with 1% silver sulfadiazine + cerium

nitrate.

Figure 4 - Evolution of the wound after serial debridement; A. After the fourth debridement, with extension to the lateral and anterior aspect of

the thighs, B. After the fifth debridement, using a dressing with 1% silver sulfadiazine + cerium

nitrate.

With a condition of acute renal failure attributed to sepsis and the use of nephrotoxic

drugs, the patient remained in the ICU.

On the thirty-second day of hospitalization, because of an apparent local and systemic

control of the infection, partial allogeneic skin grafting was performed, in mesh

(3: 1), on the raw areas to reduce the degree of spoliation (Figure 5).

Figure 5 - Evolution of the wound after serial debridement and allogeneic skin grafting; A. After sixth debridement and grafting of homogeneous skin in 3: 1 mesh; B. Dressing opening, five days after grafting, with the integration of approximately

60% of the grafted skin.

Figure 5 - Evolution of the wound after serial debridement and allogeneic skin grafting; A. After sixth debridement and grafting of homogeneous skin in 3: 1 mesh; B. Dressing opening, five days after grafting, with the integration of approximately

60% of the grafted skin.

However, five days after the grafting, the patient presented a new clinical worsening

with hemodynamic instability, evolving to death. The necropsy report defined the cause

of death as a septic shock with pulmonary and skin focus.

DISCUSSION

Polydimethylsiloxane (silicone) is a compound formed by the conjugation of silicon

with oxygen and methane. In its manufacture, it is inherently contaminated with impurities,

heavy metals, and volatile polymers. Besides, when it hardens, it ends up releasing

acetic acid, which may be responsible for the initial tissue damage after the injection.

This combination of factors contributes to the severe complications frequently observed6.

In addition to its isolated use, silicone is also intentionally associated with other

agents to increase inflammation and fibroplasia at injection sites, preventing its

migration by gravitational action. Sakurai’s formula is a well-known example of its

association with olive oil. Other sclerosing agents used are croton oil, snake venom,

and peanut oil7.

Winer et al. created the term siliconoma., in 19642, to describe the foreign body reaction similar to those already described after the

injection of oil and paraffin. These substances promote an equivalent type of anatomopathological

tissue reaction, called sclerosing lipogranulomatosis1,5,8,9.

In an attempt to eliminate, through the phagocytic activity of tissue macrophages

and circulating blood cells, the silicone can be transported by the lymphatic route

to organs at a distance, leading to embolism. Besides, its intravascular injection

can also result in immediate embolism4,10,11.

Due to the illegal nature of the practice, there are few reports of acute reactions

in this context. These patients are reluctant to seek medical attention, except in

life-threatening circumstances. The most severe systemic manifestations include pulmonary,

neurological, cardiac, hepatic, gastrointestinal involvement and sepsis12.

From a local point of view, complications range from skin color and consistency changes

to an intense inflammatory process with nodules, ulceration, necrosis, abscesses,

and fistulas. Scarring retractions and deformities are also observed. The latency

period for these sequelae appearance is variable, reaching up to 30 years. Therefore,

identifying and punishing those responsible is often difficult5,10.

According to the literature, the complete elimination of silicone deposits is not

feasible, since liquid silicone diffuses through deep tissues, forming islands of

fibrosis among healthy tissues. Thus, its eradication would culminate in very extensive

resections leading to even more severe sequelae3,5,9.

The debridement of devitalized tissues and early irrigation can minimize the damage

caused by the initial silicone hardening reaction and dilute contaminants. In addition

to surgical intervention, the use of antimicrobial dressings, intravenous antibiotics,

and systemic steroids is also recommended5,9.

Allogeneic skin grafting, as a biological dressing, is an option until the wound bed

is appropriately prepared to receive autografts or other definitive coverage. Local

or regional flaps should be used to rebuild areas with exposure to deep structures.

Despite reports of adjuvant therapies such as hyperbaric oxygen, intralesional corticosteroids,

and topical immunomodulators, there are not yet enough studies validating their effectiveness.

Liposuction does not seem to be effective in removing tissues impregnated with fibrous

oil. The intense local fibrosis alone makes aspiration with cannulas difficult and

increases the risk of injury to adjacent structures3,5.

The National Health Surveillance Agency (Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária,

Anvisa) prohibits the use of industrial-grade liquid silicone in cosmetic procedures,

and its application is considered a crime against public health provided for in the

Penal Code. For aesthetic purposes, polydimethylsiloxane (silicone) is the raw material

for many prostheses and implants and must be handled by qualified people and in a

hospital environment13.

The exclusive use of the medical product containing silicone oil authorized by Anvisa

is for the treatment of diseases of the retina to promote intraocular tamponade9,14. Therefore, its use is restricted to the doctor specialized in ophthalmology and

is prohibited for facial fillings or body contour treatment15.

CONCLUSION

The injection of industrial liquid silicone for aesthetic purposes to alter body contour

is strongly contraindicated and is considered a crime against public health provided

for in the Penal Code. Its misuse produces serious complications, challenging to treat

and potentially fatal, as described in this case report.

REFERENCES

1. Behar TA, Anderson EE, Barwick WJ, Mohler JL. Sclerosing lipogranulomatosis: a case

report of scrotal injection of automobile transmission fluid and literature review

of subcutaneous injection of oils. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993 Fev;91(2):352-61.

2. Winer LH, Sternberg TH, Lehman R, Ashley FL. Tissue reactions to injected silicone

liquids. A report of three cases. Arch Dermatol. 1964 Dez;90:588-93.

3. Hage JJ, Kanhai RC, Oen AL, van Diest PJ, Karim RB. The devastating outcome of massive

subcutaneous injection of highly viscous fluids in male-to-female transsexuals. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2001 Mar;107(3):734-41.

4. Andrews JM, Haddad CM, Ramos RR, Martins DMFS, Ferreira LM. Morbidade e mortalidade

após injeção de silicone líquido em seres humanos. A Folha Médica. 1989 Ago;99(2).

5. Freitas RJ, Cammarosano MA, Rossi RHP, Bozola AR. Injeção ilícita de silicone líquido:

revisão de literatura a propósito de dois casos de necrose de mamas. Rev Bras Cir

Plást. 2008;23(1):53-7.

6. Chasan PE. The history of injectable silicone fluids for soft-tissue augmentation.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(7):2034-40;discussion:2041-3.

7. Balkin SW. DPM injectable silicone and the foot: a 41-year clinical and histologic

history. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:1557.

8. Narins RS, Beer K. Liquid injectable silicone: a review of its history, immunology,

technical considerations, complications, and potential. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006

Set;118(3 Suppl):77S-84S.

9. Rohrich RJ, Potter JK. Liquid injectable silicone: is there a role as a cosmetic soft-tissue

filler?. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004 Abr;113(4):1239-41.

10. Gemperli R, Alonso N, Lodovici O, Pigossi N. Estudo clínico das reações sistêmicas

e locais ao uso indevido do silicone líquido e/ou óleo mineral. Rev Hosp Fac Med

S Paulo. 1984;39(4):158-62.

11. Schmid A, Tzur A, Leshko L, Krieger BP. Silicone embolism syndrome: a case report,

review of the literature, and comparison with fat embolism syndrome. Chest. 2005 Jun;127(6):2276-81.

12. Bartsich S, Wu JK. Silicone embolism syndrome: a sequela of clandestine liquid silicone

injections. A case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg.

2010;63(1):e1-3.

13. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Portal ANVISA [Internet]. Brasília

(DF): ANVISA; 2020; [acesso em 2020 Mar 10]. Disponível em: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/

14. Siqueira RC, Gil ADC, Jorge R. Cirurgia de descolamento de retina com injeção de óleo

de silicone no sistema de vitrectomia transconjuntival sem sutura de 23-gauge. Arq

Bras Oftalmol. 2007;70(6):905-9.

15. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Consultas [Internet]. Brasília

(DF): ANVISA; 2020; [acesso em 2020 Fev 10]. Disponível em: https://consultas.anvisa.gov.br/#/saude/253510028760211/

1. Hospital das Clínicas, Faculty of Medicine, University of São Paulo, São Paulo,

SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Gustavo Gomes Ribeiro Monteiro, Rua Enéas de Carvalho Aguiar 255, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 14020-130.

E-mail: monteiroggr@hotmail.com

Article received: April 14, 2019.

Article accepted: June 12, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none.