Case Reports - Year 2020 - Volume 35 -

Reconstructive surgery in the context of Covid-19: complications in the treatment of an inguinal complex wound

Cirurgia reparadora no contexto da Covid-19: complicações evolutivas no tratamento de ferida complexa inguinal

ABSTRACT

Introduction: At the end of 2019, the world saw the emergence of a new respiratory syndrome called Covid-19, caused by a new type of coronavirus, Sars-CoV-2. Classified as a pandemic, it has caused impacts of considerable magnitude.

Case Report: A 57-year-old man developed a right inguinal wound after surgical exploration for infection of a prosthesis used in a femur-popliteal bypass. The Plastic Surgery team opted for treatment with surgical debridement associated with negative pressure therapy to prepare the wound bed. In the postoperative period, he had severe acute respiratory syndrome and suspected Covid-19, requiring intubation and intensive care. A sample for RT-PCR of Sars-CoV-2 was collected, and the medications chloroquine and azithromycin were associated with the treatment. Despite intensive treatment, the patient died. The result of the RT-PCR test for the new coronavirus was positive, being released two days after death.

Discussion: The analysis of this report allows us to suppose that the patient probably contracted the new coronavirus at the hospital, as he was hospitalized for 35 days before the evolution of respiratory failure. This fact, together with its unfavorable evolution, corroborates the orientation of minimizing hospitalizations and surgical procedures as much as possible to promote more safety for the patient and the health team.

Conclusion: Inpatients are susceptible to infection with the new coronavirus and can set up a group at higher risk since many of them are already weakened.

Keywords: SARS virus; Plastic surgery; Coronavirus; Wounds and injuries; Debridement.

RESUMO

Introdução: No final de 2019, o mundo viu surgir uma nova síndrome respiratória denominada Covid-19, causada por um novo tipo de coronavírus, o Sars-CoV-2. Classificada como uma pandemia, ela tem causado impactos de magnitude ainda imensuráveis.

Relato de caso: Homem de 57 anos desenvolveu ferida inguinal direita, após exploração cirúrgica por infecção de prótese usada em bypass femoro-poplíteo. A equipe de cirurgia plástica optou pelo tratamento com desbridamento cirúrgico, associado com terapia por pressão negativa para preparo do leito da ferida. No pós-operatório, apresentou síndrome respiratória aguda grave e suspeita de Covid-19, com necessidade de intubação e de cuidados intensivos. Foi colhido amostra para RT-PCR do Sars-CoV-2 e associado ao tratamento as medicações cloroquina e azitromicina. Apesar do tratamento intensivo, o paciente foi a óbito. O resultado do exame RT-PCR para o novo coronavírus foi positivo, sendo liberado dois dias após a morte.

Discussão: A análise deste relato permite supor que o paciente provavelmente contraiu o novo coronavírus dentro do próprio hospital, pois o mesmo encontrava-se internado pelo período dos 35 dias anteriores à evolução para insuficiência respiratória. Esse fato, juntamente com sua evolução desfavorável, corrobora a orientação de minimizar ao máximo as internações e os procedimentos cirúrgicos a fim de promover maior segurança ao paciente e à equipe de saúde.

Conclusão: Pacientes internados estão susceptíveis à infecção pelo novo coronavírus e podem configurar grupo de maior de risco, uma vez que muitos deles já se encontram debilitados.

Palavras-chave: Vírus da SARS; Cirurgia plástica; Coronavírus; Ferimentos e lesões; Desbridamento

INTRODUCTION

In late 2019, the world saw a new respiratory syndrome called Covid-19 appear, caused by a new type of coronavirus, Sars-CoV-2. In March 2020, the World Health Organization classified this new disease as a pandemic, which has caused impacts of immeasurable magnitude1. In recent months, there has been a notable scientific production that sought to understand better the pathophysiology of this new disease, the origin and genetic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2, characteristics of its dissemination, pathogenesis, means of diagnosis, support protocols and treatment of patients2.

This pandemic revealed that the world was not prepared for a crisis of such proportions. The scarcity of necessary supplies (personal protective equipment, mechanical ventilators), sanitary structure (availability of beds, especially those for intensive care), and trained human resources (doctors, nursing staff, physiotherapy, etc.) is a frequent finding in coping with Covid-193. Much more than just being a health crisis, the pandemic exposes Plastic Surgery to a new challenge: how to deal with patients who need surgical treatment in the context of facing this new virus?

The speed of dissemination of the new coronavirus was higher than that of precautionary measures and preparation of health workers. Numerous simultaneous efforts have been made, such as social distance, travel restrictions, suspension of non-priority ambulatory care, interruption of elective surgeries, and maintenance of urgent / emergency surgeries or oncological cases, in addition to encouraging the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and team training. Despite this, there has been an intra-hospital Sars-CoV-2 spread. There was also the admission of patients infected with coronavirus, not only in Brazil but also in the world1.

The importance of viral dissemination by asymptomatic patients, companions, and health professionals is well known. It is estimated that about 80% of transmissions come from this group4. Following the guidelines of national and international health authorities, there was a recommendation to suspend elective surgeries and non-priority consultations in the office, in addition to adhering to social distance. Such measures, in addition to reducing patients’ exposure to the risk of infection, also increase the availability of nursing beds and intensive care to cope with the crisis.

In this article, we report the case of a patient with a complex inguinal wound treated by the Plastic Surgery team at Hospital das Clínicas, Ribeirão Preto Medical School, University of São Paulo (HCFMRP-USP). The patient evolved with acute respiratory failure, requiring intensive care. The diagnostic confirmation of Covid-19 was performed “post mortem” after a positive RT-PCR test for the new coronavirus.

CASE REPORT

A 57-year-old man with peripheral arterial obstructive disease, in the postoperative period of the right femur-popliteal bypass with a prosthesis, was hospitalized on 02/29/2020 due to infection of the prosthesis and antibiotic therapy was started intravenously. As a surgical history, he underwent left infrapatellar amputation in 2015, three femur-popliteal bypasses on the right (2015, 2017, 2018), and the re-approach of that bypass on 02/13/2020 with a finding of a thickened PTFE prosthesis, with signs of infection.

On 03/05/2020, the Vascular Surgery team performed right inguinal surgical exploration with findings of local infection, followed by surgical debridement, resulting in an inguinal wound. On the following day, the patient developed acute arterial obstruction of the right lower limb (RLL), being treated utilizing catheterized thromboembolectomy, followed by the return of the pulse in the affected limb. However, there was a progressive worsening of tissue perfusion, and on 03/13/2020, right suprapatellar amputation was performed.

The Plastic Surgery team, which was already in a contingency and relocation regime with the minimum possible individual exposure due to the pandemic, was called in to assess the right inguinal wound on 03/31/2020. Upon examination, we identified a complex 10 x 8 cm wound, with the presence of sloughs and areas with granulation tissue, with no signs of infection and absence of exposure of large vessels (Figure 1). We opted for treatment with surgical debridement associated with negative pressure therapy (NPT) to prepare the wound bed5-6 (Figure 2).

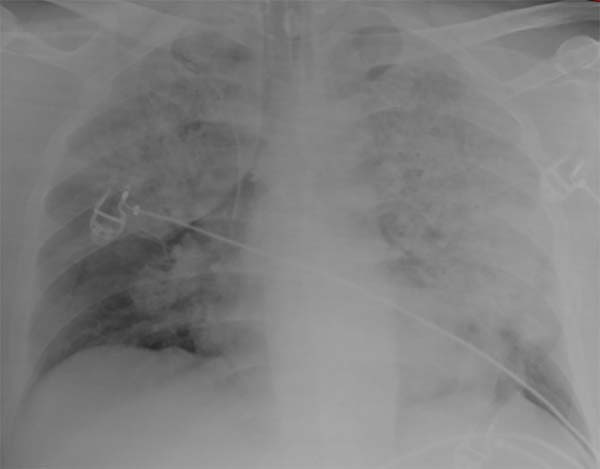

After three days, the patient developed a febrile peak, tachycardia, and tachypnea, progressing to severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the need for intensive care. After transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU), orotracheal intubation was performed, and the patient was in respiratory and contact isolation, according to the HCFMRP-USP protocol during the Covid-19 pandemic. Chest X-ray performed on the bed showed an infiltrate bilateral interstitial (Figura 3). According to the SAPS 3 system, the calculation of the probability of death upon admission to the ICU was 90.98%7.

A sample for RT-PCR of Sars-CoV-2 was collected due to SARS suspicion by coronavirus. Medications chloroquine and azithromycin were associated with the treatment, according to the HCFMRP-USP protocol. On 04/04/2020, after maintaining a febrile plateau refractory to pharmacological measures, the patient developed hypotension and the need for vasoactive drugs, maintaining protective ventilation.

Despite intensive treatment and pharmacological measures, the patient maintained hemodynamic instability with a rising vasoactive drug, being diagnosed with refractory septic shock. At the same time, he worsened renal function with the indication for renal replacement therapy, but without hemodynamic conditions for hemodialysis.

The evolution of the clinical picture was unfavorable, with cardiac arrest in pulseless electrical activity. Non-resuscitation was chosen due to the refractoriness of the measures instituted, and he was then declared dead on 04/05/2020. The result of the RT-PCR test for the new coronavirus was positive, being released two days after death.

Medical record review data reveal that this patient shared the wardroom with another patient who also developed SARS on 02/04/2020, also in need of intensive care and orotracheal intubation. This patient was also diagnosed with infection by the new coronavirus confirmed by RT-PCR.

DISCUSSION

The new scenario presented by the coronavirus pandemic has led to a series of social restrictions and changes in hospital routines1. The rediscussion and continued elaboration of patient and health team safety protocols are necessary since about 80% of those infected with Sars-CoV-2 can be asymptomatic, being, therefore, a relevant source of transmission4.

The analysis of this report allows us to suppose that the patient probably contracted the new coronavirus within the hospital, as he was hospitalized for 35 days before the evolution to respiratory failure. This fact, together with its unfavorable evolution, corroborates the orientation to minimize hospitalizations and surgical procedures as much as possible to promote more excellent safety for the patient and the health team1. Besides, the situation reinforces the need to use PPE and reinforce hygiene measures8. Another essential factor to be considered would be the relocation of assistant teams and resident doctors to reduce exposure and chance of infection by the medical team9. Until the writing of this article, no member of our team manifested a picture suggestive of contamination by the new coronavirus.

CONCLUSION

As reported in this case, hospitalized patients are susceptible to infection with the new coronavirus and may be at a higher risk group, since many of them are already weakened. Plastic surgery is also included in this context since it performs treatment of patients with complex wounds that may have multiple comorbidities, and that may require hospitalizations for prolonged periods. We emphasize the need to protect patients and professionals with the use of PPE to minimize the risk of contamination with the new coronavirus that causes the Covid-19 pandemic.

REFERENCES

1. COVIDSurg Collaborative. Global guidance for surgical care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Br J Surg. 2020 Apr 15; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs.11646

2. Wang CJ, Ng CY, Brook RH. Response to COVID-19 in Taiwan: big data analytics, new technology, and proactive testing. JAMA. 2020 Mar;323(14):1341-2. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3151

3. Ranney ML, Griffeth V, Jha AK. Critical supply shortages - the need for ventilators and personal protective equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 25; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2006141

4. Li R, Pei S, Chen B, Song Y, Zhang T, Yang W, et al. Substantial undocumented infection facilitates the rapid dissemination of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV2). Science. 2020 Mar 16; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb3221

5. Coltro PS, Ferreira MC, Batista BP, Nakamoto HA, Milcheski DA, Tuma Júnior P. Role of plastic surgery on the treatment complex wounds. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2011 Nov/Dec;38(6):381-6.

6. Lima RVKS, Coltro PS, Farina Júnior JA. Negative pressure therapy for the treatment of complex wounds. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2017 Jan/Feb;44(1):81-93. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/0100-69912017001001

7. Silva Junior JM, Malbouisson LMS, Nuevo HL, Barbosa LGT, Marubayashi LY, Teixeira IC, et al. Aplicabilidade do escore fisiológico agudo simplificado (SAPS 3) em hospitais brasileiros. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2010;60(1):20-31. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-70942010000100003

8. Bartoszko JJ, Farooqi MAM, Alhazzani W, Loeb M. Medical masks vs N95 respirators for preventing COVID-19 in health care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2020 Apr 4; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.12745

9. Nassar AH, Zern NK, McIntyre LK, Lynge D, Smith CA, Petersen RP, et al. Emergency restructuring of a general surgery residency program during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: the University of Washington experience. JAMA Surg. 2020 Apr 6; [Epub ahead of print]. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1219

1. University of São Paulo, Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, Ribeirão Preto,

SP, Brazil.

Institution: Plastic Surgery Division – Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto of USP, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil.

VGS Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, conceptualization, data curation, final manuscript approval, writing - original draft preparation.

PSC Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, conceptualization, final manuscript approval, supervision, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing.

HOCG Analysis and/or data interpretation, data curation, final manuscript approval.

DHH Analysis and/or data interpretation, data curation, final manuscript approval.

GMAS Analysis and/or data interpretation, data curation, final manuscript approval.

JAFJ Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, final manuscript approval, project administration, supervision, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author: Pedro Soler Coltro, Av. Bandeirantes 3900, Câmpus Universitário, Monte Alegre, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 14048-900. E-mail: psc@usp.br

Article received: April 21, 2020.

Article accepted: April 30, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter