Introduction

Highly effective procedures used for facial rejuvenation include injectable neurotoxins,

soft-tissue fillers, and chemical peels. Soft-tissue fillers have an impressive ability

to volumize and reshape aging, sagging skin with a small time commitment and minimal

side effects. A variety of filling agents have been approved by the United States

Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to correct moderate to severe facial wrinkles such

as hyaluronic acid, poly-l-lactic acid, calcium hydroxyapatite, and polymethylmethacrylate.

Although not FDA approved and forbidden in many countries for the treatment of facial

aesthetic contours, silicone is used “off-label” for cosmetic purposes for treating

acne scars or performing facial augmentation.

Reported complications after soft-tissue augmentation may be related to poor injection

technique or the filler material itself. Complications such as visible product, hypertrophic

scarring, nodule formation, and the Tyndall effect (bluish discoloration from hydroxyapatite

fillers) can occur if the soft-tissue synthetic materials are placed too superficially.

Persistent and painful erythematous nodules have been associated with every type of

injectable filler as granulomatous reactions. Their treatment ranges from antibiotics

to surgical removal.

Here we present the case of a patient who underwent static lip reanimation for facial

nerve damage following nodule removal as a filler complication.

Case report

A 50-year-old woman presented at our clinic with a lower lip deformity. She had a

history of facial rejuvenation using silicone to restore the volume of the nasolabial

folds and cheeks. Persistent erythematous nodules granulomatous reactions occurred

and were removed surgically.

On examination 2 years after primary surgery, she had a bilaterally elongated upper

lip, a right lower lip drop with evident lip dynamic distortion when she smiled, and

bilateral cheek deformity probably due to marginal mandibular nerve damage (Figure 1). Using a flexible ruler, the distances of the modiolus to the cupid’s and commissure

to the cupid’s bow were 4.5 and 3.5 cm on the paralyzed side and 4 and 3 cm on the

non-paralyzed side.

Figure 1 - Patient presented with a right lower lip drop and evident bilateral cheek deformity.

Figure 1 - Patient presented with a right lower lip drop and evident bilateral cheek deformity.

Preoperative markings in unilateral facial palsy are essential. With the patient seated

upright, the nasolabial fold and cheek deformities were marked. A “modified bull’s

horn approach” was taken to the upper lip lift1. The flap markings included the “bull’s horn” drawn around the nasal wings and columella

and its pedicle along the right nasolabial fold (Figure 2). A line was drawn from the columellar-labial fold and extended laterally around

the nasal wings to define the superior limit of the bull’s horn flap. Another line

was drawn parallel to the first one in a lower position to define the inferior border

of the flap, meeting the upper one at the lateral edges. Under local anesthesia and

sedation, the flap was de-epithelized, and a dermoadiposal flap was harvested from

the lateral left margin to the lateral right margin, and its pedicle was left attached

to the upper ptotic right lip. Using the open tip of a small liposuction cannula,

the flap was tunneled and fixed directly in a C-loop fashion using U stitches, and

the flap was transfixed to the periosteum of the zygomatic arch. The traction tension

of the flap was adjusted to balance the paralyzed and nonparalyzed sides of the upper

and lower lips. During surgery, a first fat-graft injection was also made to correct

cheek contour deformity, while a second fat-graft session was planned 3 months later

to improve the aesthetic results (Figure 3).

Figure 2 - Preoperative markings. With the patient seated upright the nasolabial folds and cheeks

deformity were marked. A "modified bull's horn" upper lip lift markings were carried

out around the nasal wings and columella and along the right nasolabial fold.

Figure 2 - Preoperative markings. With the patient seated upright the nasolabial folds and cheeks

deformity were marked. A "modified bull's horn" upper lip lift markings were carried

out around the nasal wings and columella and along the right nasolabial fold.

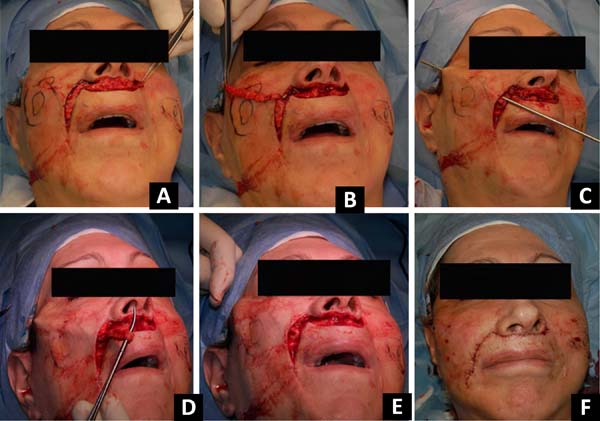

Figure 3 - Intraoperative view. The flap was deepithelized (A) and a dermoadiposal flap was harvested (B). By the use of the open tip of a small liposuction cannula, the distal portion of

the flap was tunneled and fixed in a C-loop fashion (C,D). The traction tension of the flap was adjusted to balance the length of the paralyzed

and nonparalyzed segments of the upper and lower lips (E,F).

Figure 3 - Intraoperative view. The flap was deepithelized (A) and a dermoadiposal flap was harvested (B). By the use of the open tip of a small liposuction cannula, the distal portion of

the flap was tunneled and fixed in a C-loop fashion (C,D). The traction tension of the flap was adjusted to balance the length of the paralyzed

and nonparalyzed segments of the upper and lower lips (E,F).

Fat tissue was harvested using dry technique with a 3-mm multi-hole barbed cannula

and a 10-mL syringe under manually generated negative pressure. The fat was centrifuged

at 1000 rpm for 3 minutes and finally injected with a 19G needle. The high-density

fraction of the concentrated adipose tissue was used to restore the cheek deformities,

while the low-density fraction was used for aesthetic refinements of the face2.

No significant complications were observed, and the patient reported no functional

limitations or dissatisfaction with the aspect of the scars in the nasolabial fold

or around the nasal wings and columella. The upper and lower lips appeared to be well

positioned with a slight deviation of the cupid’s bow toward the reconstructed side

because of the overcorrection. An adequately shaped, intense smile was observed despite

some incoordination with the non-paralyzed side. Postoperatively, the distances of

the modiolus to the cupid’s bow and commissure to the cupid’s bow were 4 and 3 cm,

respectively, on both sides. Balance and adequate positioning of philtrum on the median

line were evaluated, dividing the distance from the paralyzed side with the sum of

the measurements of the paralyzed and non-paralyzed sides. The pre- and postoperative

values of 53.3% and 50%, respectively, for the modiolus and commissure distances suggested

a static good outcome. The results at 3 years of follow-up are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 - Results at three-year of follow-up.

Figure 4 - Results at three-year of follow-up.

Discussion

Facial paralysis is a profoundly disfiguring condition with significant psychological

and functional consequences. Prior to the introduction of surgical reanimation, treatment

was based on medical therapies (botulinum toxin injection) and prostheses3. Over time, static surgical procedures were introduced; thereafter, the use of temporalis

and masseteric muscle transfers became popular.

Recently, nerve grafts and free muscle flap transfers have been considered by many

surgeons the ideal procedures for long-standing facial paralysis to restore symmetry

at rest and during smiling. However, facial movements are generally unidirectional

and localized and cannot precisely reproduce the function of multiple muscles responsible

for oral expressions4,5.

Differences in patients, facial perceptions, and various treatment strategies preclude

a direct comparison of reconstructive techniques.

Tissue transfer is correlated to major trauma and donor site morbidity; it can require

a two-stage operation, prolonged re-innervation time, and multiple revision procedures

over time6. Even if it is performed at specialized centers, a patient’s baseline health status

requires evaluation. Thus, elderly or frail patients may not choose microneurovascular

tissue transfer.

Static restoration of the lower face is generally used to achieve symmetry at rest.

Slings such as harvested tensor fascia lata are commonly used7. Even if static procedures cannot achieve mimic movements, they generate limited

trauma and can be completed in a single surgical stage.

Here we presented an easy way to correct a lip deformity using a modified bull’s horn

approach. The original technique was first described by Ramirez et al1 for an upper lip lift. It consisted of an excision of the white part of the upper

lip directly beneath the nose in the shape of a bull’s horn, with advancement of the

inferior border of the incision to the area directly beneath the nose. We used the

same approach to harvest a dermoadiposal flap by using commonly discarded tissues

and adding the pedicle flap markings in the nasolabial fold with a final concealed

scar.

The patient was informed of the different techniques available to correct her defect

as a consequence of facial nerve damage. She did not suffer from any particular disease

and was considered a good candidate for a temporalis muscle transposition with a facelift.

The patient refused this option because she did not want to undergo an invasive procedure.

Because she complained of lower lip elongation, another option was offered to correct

her defect as described.

A fat transfer procedure was carried out simultaneously with the flap transfer to

correct a volume defect. At 3 months after the first surgery, a second fat transfer

session was planned to improve the residual cheek deformity bilaterally as a consequence

of the nodule removal. At 3 years of follow-up, the asymmetry correction appeared

stable and the dermoadiposal flap was a good autologous suspension material for static

correction of the lip deformity.

COLLABORATIONS

|

AC

|

Realization of operations and/or trials, Supervision

|

|

RL

|

Conception and design study, Final manuscript approval, Writing - Original Draft Preparation,

Writing - Review & Editing

|

REFERENCES

1. Ramirez OM, Khan AS, Robertson KM. The upper lip lift using the ‘bull’s horn’ approach.

J Drugs Dermatol. 2003 Jun;2(3):303-6.

2. Caggiati A, Germani A, Di Carlo A, Borsellino G, Capogrossi MC, Picozza M. Naturally

adipose stromal cell-enriched fat graft: comparative polychromatic flow cytometry

study of fat harvested by barbed or blunt multihole cannula. Aesthet Surg J. 2017

May;37(5):591-602. PMID: 28052909 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjw211

3. Biglioli F, Frigerio A, Colombo V, Colletti G, Rabbiosi D, Mortini P, Dalla ET, Lozza

A, Brusati R. Masseteric-facial nerve anastomosis for early facial reanimation. J

Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2012 Feb;40(2):149-55. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2011.03.005

4. Biglioli F, Frigerio A, Autelitano L, Colletti G, Rabbiosi D, Brusati R. Deep-planes

lift associated with free flap surgery for facial reanimation. J Craniomaxillofac

Surg. 2001 Oct;39(7):475-81. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcms.2010.09.003

5. Chuang DC. Technique evolution for facial paralysis reconstruction using functioning

free muscle transplantation - experience of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. Clin Plast

Surg. 2002 Oct;29(4):449-59. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0094-1298(02)00021-4

6. Harrison DH, Grobbelaar AO. Pectoralis minor muscle transfer for unilateral facial

palsy reanimation: an experience of 35 years and 637 cases. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet

Surg. 2012;65(7):845-50. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2012.01.024

7. Rose EH. Autogenous fascia lata grafts: clinical applications in reanimation of the

totally or partially paralyzed face. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005 Jul;116(1):20-32;discussion:33-5.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000169685.54862.18

1. Istituto Dermopatico dell’Immaticolata IDI, Rome, Italy.

Corresponding author: Rosaria Laporta Via dei Monti di Creta, 104, Rome, RM, Italy. Zipe Code: 00167 E-mail: r.laporta@idi.it

Article received: November 11, 2018.

Article accepted: April 16, 2019.

Institution: Istituto Dermopatico Dell’immacolata, Idi, Irccs, Rome, Italy.

Conflicts of interest: none.