Case Report - Year 2019 - Volume 34 - Issue 3

Reverse posterior interosseous flap of the forearm for the surgical treatment of electric hand trauma: Case report

Retalho interósseo posterior reverso do antebraço para o tratamento cirúrgico do trauma elétrico da mão: relato de caso

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Lesions affecting the hands with significant skin loss often require flaps for early coverage, as these permit faster healing. Among the various options, the reverse posterior interosseous flap of the forearm is most commonly used for defects involving the back of the hand and wrist due to low complication rates. Normally, this flap is not used for the reconstruction of defects in the palmar region since its distal reach is insufficient. Case report: We present the case of a male patient with third-degree electrical burns on his right palm, whose reconstruction was performed on the 14th day postinjury using the reverse posterior interosseous flap of the forearm after conservative debridement. The patient presented good postoperative evolution, without long-term complications or functional sequelae. Conclusion: The reverse posterior interosseous flap of the forearm permits adequate coverage of palm injuries, preserving its functionality.

Keywords: Burns; Burns by electric current; Surgical flaps; Techniques for wound closure; Hand injuries.

RESUMO

Introdução: Lesões que acometem as mãos com importante perda cutânea frequentemente requerem retalhos para cobertura precoce, visto que permitem melhor reabilitação. Dentre as opções, o retalho interósseo posterior reverso do antebraço é o mais utilizado para defeitos no dorso da mão e punho, com baixas taxas de complicações. Normalmente, esse retalho não é utilizado para a reconstrução de defeitos em região palmar, já que geralmente não alcança esse local.

Relato de caso: Apresentamos o caso de um paciente com queimadura elétrica de terceiro grau, em palma da mão direita, cuja reconstrução foi realizada com o uso do retalho interósseo posterior reverso do antebraço, após debridamentos conservadores, no 14o dia após a queimadura. O paciente apresentou boa evolução pós-operatória, sem complicações ou sequelas funcionais a longo prazo.

Conclusão: O retalho interósseo posterior reverso do antebraço permite cobertura adequada de lesões em palma da mão, preservando sua funcionalidade.

Palavras-chave: Queimaduras; Queimaduras por corrente elétrica; Retalhos cirúrgicos; Técnicas de fechamento de ferimentos; Traumatismos da mão

INTRODUCTION

The coverage of defects caused by electrical burns on the upper limbs is challenging, especially when bones, tendons, or joints are exposed. Among the options of local flaps for the coverage of deep hand lesions, we pay special attention to the pedicles in the radial or ulnar arteries1; however, both cause great morbidity to the donor area and sacrifice one of the main arteries responsible for hand irrigation2. Distant flaps, such as groin or abdominal flaps, are reliable alternatives; however, they require more than one surgery and may result in prolonged immobility, thus impairing rehabilitation3.

The reverse posterior interosseous flap of the forearm is a reproducible alternative for covering hand lesions with less morbidity in the donor area, low loss rates, and excellent aesthetic results4. Originally described as a fasciocutaneous flap with rotation to the elbow region, it is maintained by the posterior interosseous artery of the forearm. It presents a modification based on the reverse flow of this artery through its distal anastomosis to the anterior interosseous artery, allowing rotation towards the hand; however, in 18% of cases, this anastomosis does not exist, thus making use of this flap impossible5.

It is a flap commonly used to cover lesions on the back of wrists and hands, thumbs, and first commissures since it does not usually reach the palmar region6. Thus, we present the use of the posterior reverse forearm interosseous flap to cover the palm of the right hand in a patient with 3rd degree electrical burn injuries.

CASE STUDY

A healthy 33-year-old male patient was admitted to the Hospital das Clínicas of the University of São Paulo Medical School (HC-FMUSP) 40 min after suffering an electrical burn caused by contact with a metal object in a high voltage (10,000 V) power grid. After initial polytraumatic care, he was transferred to the intensive care burn unit for cardiac monitoring and surveillance of renal function.

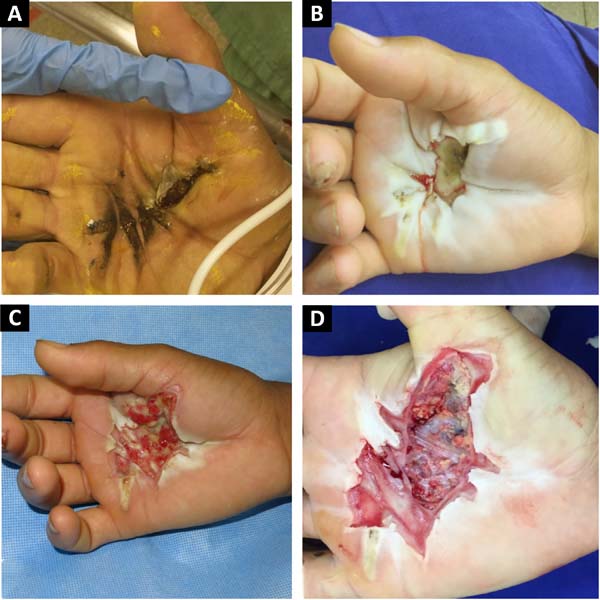

He presented with 3rd degree burns on 3% of his body surface. His right palm (Figure 1A) was the entry point and his left shoulder (posterior surface) was the exit point. In addition, there was a deep 2nd degree burn on the anterior surface of his left arm.

The patient underwent three conservative debridements of the burned area of his hand, delimiting a palmar lesion of approximately 8.5 cm x 3.5 cm and to a depth of 1.5 cm (Figures 1B, 1C, and 1D). In the posterior surface of his left shoulder, the defect was 2.5 cm deep and approximately 8 cm in diameter.

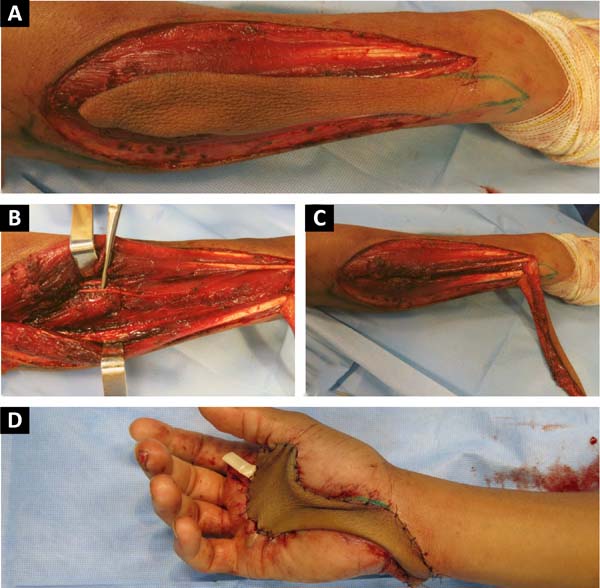

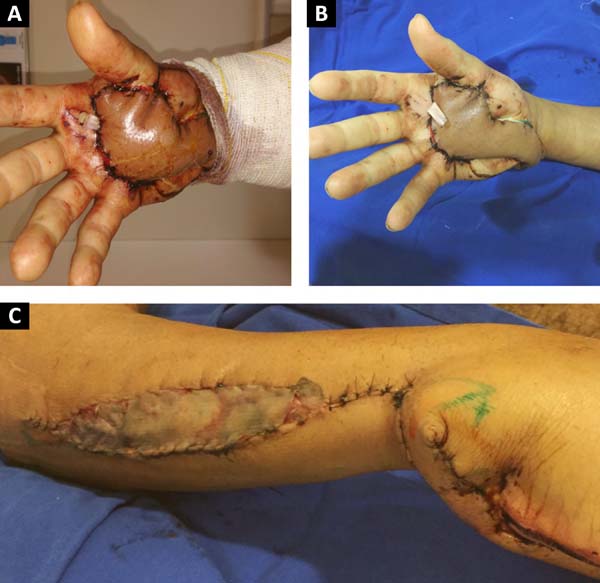

We chose to perform a reverse posterior interosseous flap of his right forearm on the 14th day postinjury (Figure 2). The 15 cm x 4 cm dissected flap allowed adequate coverage of the entire lesion on the palmar surface requiring skin grafting obtained from the inguinal region to close the donor area of the flap on the forearm. The patient’s shoulder lesion was closed with a local advancement flap during the same surgery. On the 5th postoperative day, the interosseous flap was viable, without congestion or ischemia, and the grafted area had 100% integration (Figure 3).

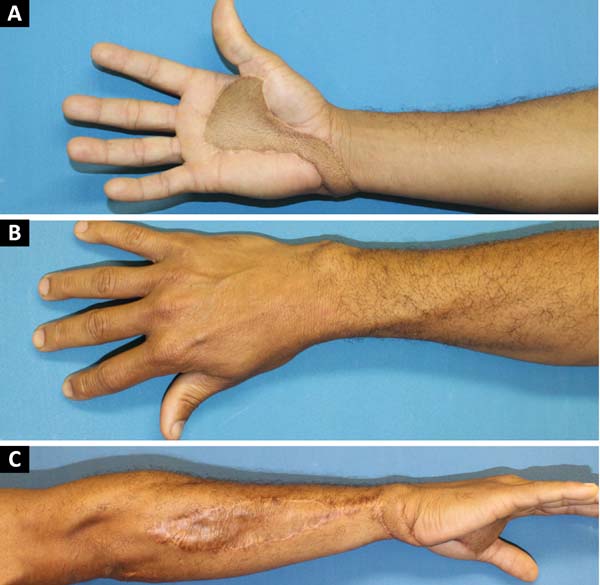

After discharge from the hospital, the patient began physiotherapy to improve the motricity of his right hand. He has maintained satisfactory progress over the past 3 years without complaints (Figure 4), with preserved functionality of his right hand and an adequate aesthetic aspect.

DISCUSSION

Deep lesions of the hand tend to cause exposure of noble structures, requiring flaps for adequate coverage and better rehabilitation. The flaps used should be versatile to allow for the coverage of a variety of lesions, allow reproducible technical execution, and possess reliable vascularization7.

The reverse posterior interosseous flap of the forearm is a long flap with many advantages, having been first described by Zancolli and Angrigiani in 19868. It has proven useful for covering defects on the backs of hands and wrists. It has proximity to the receiving bed of the hand, a wide rotational arch, minimal lesions to the lymphatic vessels, preservation of the main vessels that perfuse the forearm and the hand (radial and ulnar arteries), and no requirement for microsurgical techniques (except for potential primary closure of the donor area, which was not observed in our case)3. In addition, it is thin, has good flexibility and skin texture (similar to that of the hand), and permits coverage of various tissues, such as bones, muscles, tendons, and fascia.

Despite being considered in the literature as being easily and reproducibly obtained, the flap’s anatomical variations of its perforating vessel have already been described, as well as lesions of the posterior interosseous nerve of the forearm and rupture of the distal anastomosis. It is therefore important to proceed carefully during the dissection and have anatomical knowledge of the region9.

The main complication of the posterior reverse interosseous flap of the forearm is congestion by occlusion of the venous return after its rotation which may progress to necrosis7. Neuwirth et al., in 20134, after evaluating 40 flaps to cover wrist and back of the hand lesions, reported the occurrence of partial necrosis at 15% and of total necrosis at 5%. The dissection of a peninsular flap, as in the case described, allowed the inclusion of distally located perforators, reducing the possibility of the occurrence of congestion and necrosis5.

In the study by Kai et al., in 20136, who evaluated the reverse forearm flap based on the posterior interosseous artery for reconstruction of the first hand commissure in 12 burn patients, demonstrated its safety with no resulting cases of congestion or necrosis in his series. He recommended an interval of 2 weeks before reconstruction after electrical burns. This allows for multiple debridements and better delineation of the necrotic area, which develops during the first 2 weeks, similar to that observed in our case. In severely burned patients, this interval can be extended to 3 to 4 weeks6.

According to Gavaskar, in 201010, the distal reach of the flap in his series was to the proximal thumb joint. Defects beyond this point may be difficult to cover, since traction in the pedicle may cause vascular insufficiency. In the case reported, the flap maintained its irrigation through the anterior interosseous artery, with excellent perfusion even after its rotation to the palmar face and anterior positioning.

CONCLUSION

The forearm posterior interosseous flap with a reverse rotation arch is a good option for treating deep palm injuries, allowing adequate coverage, and preserving functionality.

COLLABORATIONS

|

RCL |

Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

WMM |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

PTJ |

Final manuscript approval, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

DAM |

Final manuscript approval, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

HAN |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Final manuscript approval, Realization of operations and/or trials, Writing - Review & Editing |

|

RG |

Final manuscript approval, Writing - Review & Editing |

REFERENCES

1. El-Shazly M. Fashioning reversed axial pattern forearm tissues in different challenging conditions of the forearm territory as a reliable substitute for free tissue transfer. Acta Chir Plast. 2012;54(2):53-8. PMID: 23565845.

2. Hekner DD, Abbink JH, van Es RJ, Rosenberg A, Koole R, Van Cann EM. Donor-site morbidity of the radial forearm free flap versus the ulnar forearm free flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Aug;132(2):387-93. PMID: 23584626. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e318295896c

3. Baylan JM, Chambers JA, McMullin N, et al. Reverse posterior interosseous flap for defects of the dorsal ulnar wrist using previously burned and recently grafted skin. Burns. 2016 Mar;42(2):e24-30. PMID: 26652146. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2015.06.020

4. Neuwirth M, Hubmer M, Koch H. The posterior interosseous artery flap: clinical results with special emphasis on donor site morbidity. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2013 May;66(5):623-628. PMID: 23375239. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2012.12.018

5. Fujiwara M, Kawakatsu M, Yoshida Y, Sumiya A. Modified posterior interosseous flap in hand reconstruction. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2003 Sep;7(3):102-109. PMID: 16518227.

6. Kai S, Zhao J, Jin Z, et al. Release of severe post-burn contracture of the first web space using the reverse posterior interosseous flap: our experience with 12 cases. Burns. 2013 Sep;39(6):1285-1289. PMID: 23523223. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burns.2013.02.002

7. Acharya AM, Bhat AK, Bhaskaranand K. The reverse posterior interosseous artery flap: technical considerations in raising an easier and more reliable flap. J Hand Surg Am. 2012 Mar;37(3):575-582. PMID: 22321438. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.12.031

8. Zancolli E, Angrigiani C. Posterior interosseous island forearm flap. J Hand Surg Br. 1988 May;13(2):130-35. PMID: 3385286.

9. Zaidenberg EE, Farias-Cisneros E, Pastrana MJ, Zaidenberg CR. Extended posterior interosseous artery flap: anatomical and clinical study. J Hand Surg Am. 2017 Mar;42(3):182-189. PMID: 28259275. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.01.004

10. Gavaskar AS. Posterior interosseous artery flap for resurfacing posttraumatic soft tissue defects of the hand. Hand. 2010 Apr;5(4):397-402. PMID: 22131922. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-010-9267-7

1. Hospital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo,

SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Rodolfo Costa Lobato Rua Doutor Melo Alves, nº 55, CJ 23, Cerqueira César, São Paulo, SP, Brazil. Zip Code: 01417-010. E-mail: rodolfolobato49@yahoo.com.br

Article received: October 22, 2018.

Article accepted: April 21, 2019.

Institution: Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter