INTRODUCTION

It is well known that the facial nerve can be injured in virtually every face

lift. Despite its importance, it is difficult to find literature on this topic.

Most articles on rhytidoplasty and facial nerve injury are from the early 70’s

to the late 80’s and focus almost exclusively on how to avoid facial nerve

lesions through anatomic dissections. There are very few published studies on

the management of nerve injury and they focus mostly on treatment of complete

nerve transection which comprises 2.6% of operated cases. It is also surprising

that on searching for the terms: “face lift/lifting + facial palsy (FP)” or

“rhytidoplasty/rhytidectomy + facial palsy”, in the PubMed database, there are

no answers that fulfill the search criteria1,2.

Currently there is no concise data regarding the incidence of partial or total

facial nerve injury during cosmetic facial procedures, as it is probably under

reported. A complete or an incomplete facial paralysis after a facial procedure,

may lead to a very uncomfortable situation between the patient and the surgeon,

which is why we recommend a guide in this article to help avoid, identify, and

manage a facial nerve injury in the event of a face lift surgery.

DISCUSSION

Assessment - Facial palsy before surgery: Pre-operative Clinical

Examination.

Despite our best efforts to avoid nerve injury during a face lift surgery, it

may still occur. However, it is important to note that in a significant

number of cases, patients may already have a certain degree of facial

paralysis or pre-operative weakness that remains unnoticed in a routine

consultation. It is quite difficult to identify the signs of a very mild

palsy if the surgeon is not used to treat such cases on a regular basis.

Even patients may not have noticed any degree of asymmetry until the surgeon

points it out but will certainly refer to it in a post- op situation.

To make the pre-op facial assessment as simple as possible, we suggest a

systematic approach to the facial examination. A structured history and

clinical examination of the patient allows for accurate treatment planning

and anticipation of problems that may be exacerbated by surgery3.

Evaluation of facial asymmetry and spontaneity of facial motion can be

performed while eliciting a routine medical history. With regard to

functional history, a “top down” approach is utilized in a systematic

manner, beginning with the brow. An ophthalmic and nasal history is

obtained, and the patient is questioned regarding oral continence and

speech. The surgeon should always include a history of Bell’s palsy.

Recurrence or new onset palsy, three to five weeks post-op in our experience

is possible but rare and undesirable.

A physical examination is also performed from the brow downwards. The

presence or absence of rhytids and brow ptosis is noted. An asymmetric brow

ptosis is common and is seen clearly over a period of time in photos. The

upper lid is also examined for dermatochalasis and lid retraction. The

patient is asked to close the eyes and any lagophthalmos is measured. The

lower lid position is inspected for an ectropion and a snap test is

performed3.

The nose is examined to exclude any fixed nasal obstruction and a Cottle’s

test is performed to determine any nasal valve collapse4. Any midface ptosis or nasolabial crease asymmetry is

evaluated. The mouth is examined at rest, with the amount of commissure

droop and deviation of the philtrum to the contralateral side measured, if

present. The excursion of the commissure is quantified and the degree of

tooth show and shape of the smile are noted5-7. The lower

lip is observed for any signs of weak depressor anguli oris function,

indicating involvement of the mandibular division8. It is also very important to take sequential photos

of the patient, at rest and in motion, before and after surgery, and note if

there are any complications (Figura 1).

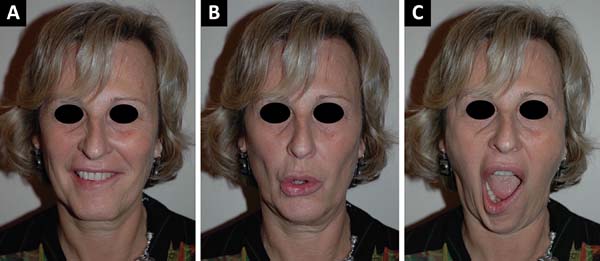

Figure 1 - Pre-operative clinical examination showing minimal facial

palsy: mandibular branch. A: Slightly visible

during smiling; B: Protruding the lips;

C: More visible while opening the mouth

(Personal archives).

Figure 1 - Pre-operative clinical examination showing minimal facial

palsy: mandibular branch. A: Slightly visible

during smiling; B: Protruding the lips;

C: More visible while opening the mouth

(Personal archives).

Avoiding facial nerve injury during a face lift

Several published articles have focused on this particular topic. It is clear

that a deep knowledge of the facial anatomical structures and the anatomy of

the facial nerve is very important. We recommend an article published in the

late 70’s by Baker2 and a textbook by

Brook Seckel titled: Facial Danger Zones (Figura 2)9, for surgeons

who perform face lifts. Nevertheless, to master facial anatomy, we should

always dissect in a very meticulous way, because the anatomy of high-risk

areas is extremely variable and changes from patient to patient2,10.

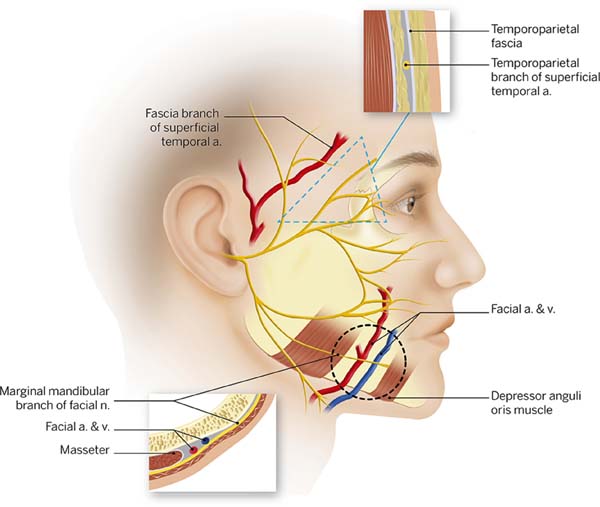

Figure 2 - Facial “danger zones” according to Seckel, encompassing the

temporal and marginal mandibular branches of the facial nerve,

respectively

9.

Figure 2 - Facial “danger zones” according to Seckel, encompassing the

temporal and marginal mandibular branches of the facial nerve,

respectively

9.

Attention to minute details is as important as the dissection itself. Caution

should be used while injecting solutions using fine needles or small

cannulas. We are very permissive with the volume injected, using about 200cc

of a 1:500.000 adrenaline solution. Intra-op anesthetic solutions are best

avoided. Hydro dissection is recommended as it facilitates the undermining

tissue and avoids unnecessary sharp dissections which could lead to less

risk of inadvertent lesions and hematoma formation.

A blunt dissection is preferred especially for sub Superficial muscular

aponeurotic system (SMAS) techniques. Trepsat dissectors (Pouret medical)

are used routinely for both facial and neck approaches which makes a

complete nerve transection virtually impossible (Figura 3).

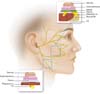

Figure 3 - Picture according to May, representing common areas of nerve

injury during a facelift and the associated anatomical

features

30.

Figure 3 - Picture according to May, representing common areas of nerve

injury during a facelift and the associated anatomical

features

30.

Suturing and hemostasis techniques are also important. Avoid placing deep

sutures in the SMAS, and preferentially place them along the axis of the

major facial nerve branches. A surgeon must also prevent excessive traction

and undue stretching2. During

hemostasis, use of a bipolar cautery is advised and not large clamps or

forceps, to minimize the electrocoagulation trauma (Figura 4). If there is a doubt regarding a nerve branch

injury, a neurostimulator must be readily available at the operation room,

to confirm any suspicion. It is important that the patient should not be

curarized.

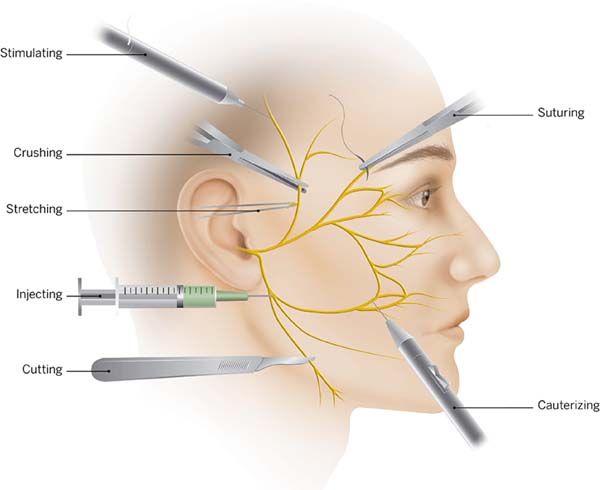

Figure 4 - Schema showing tips on how to avoid facial nerve injury

during a facelift dissection, according to Baker

2.

Figure 4 - Schema showing tips on how to avoid facial nerve injury

during a facelift dissection, according to Baker

2.

Nerve Section observed per-op

Occasionally the surgeon will be able to identify the damaged branch of the

facial nerve. As the dissection goes towards the nasolabial fold, the nerves

become less thick, which makes it difficult to correctly identify the

anatomy with the naked eye. Several studies have been published describing

surface anatomy landmarks correlating to the nerve divisions12-14 but the logical step is to test the assumed damaged

branch and the surrounding ones with a neurostimulator, to avoid

misidentification.

After this step, the nerve is sutured. Dissection of the proximal and distal

ends of the nerve is done under magnification. A check is done to see if

there is any loss of substance and an epineural suture is performed with

non-absorbable 10 or 9.0 nylon. In case of traction of the nerve, nerve

grafts are recommended, which are usually harvested from the great auricular

nerve or the sural nerve15.

Post op paralysis: What should be done?

Diagnostic

In a majority of cases the surgeon will face the onset of paralysis

during post-op. Whenever possible, evaluating the facial mimetic muscles

at the end of the surgery is a good way to differentiate surgical trauma

from other post-op causes such as Bell’s palsy. It is important to have

a very strict follow-up and take pictures at every single contact with

the patient.

To clinically assess the severity of peripheral facial nerve palsy

various scoring systems are available. In our opinion, the most suitable

facial nerve grading system is the Muscle testing of Freyss (Chart 1). This scale allows each

muscle function to be evaluated separately, which is different from

other grade systems, such as the House-Brackmann Grading System, which

assesses groups of facial muscles. The system relies on evaluation of

the degree of voluntary excursion of the facial muscles, evaluating ten

muscles groups and attributing scores from 0 to 3 for each muscle, for a

total score ranging from 0 to 3016. Evaluation is usually limited to two or three muscles,

according to the injured nerve branch.

Chart 1 - Muscle testing of Freyss

16.

| Ten facial muscles |

Score |

Muscular contraction |

| Frontalis |

Wrinkles forehead and raises

eyebrows

|

0 |

No contraction |

| Corrugator Supercilii |

Pulls eyebrows medially and down |

1 |

Minimal contraction |

| Orbicularis oculi |

Closes eyelids |

2 |

Wide excursion but weak contraction |

| Procerus |

Pulls medial angle of eyebrow down

producing wrinkles over bridge of nose

|

3 |

Normal contraction |

| Dilator naris muscle |

Expands the nostrils |

| Orbicularis oris |

Closes and protrudes lips |

Total Score (0-30) |

Grade of Facial palsy |

| Risorius |

Pulls corner of mouth lateral |

Score 20-30 |

Slight |

| Zygomaticus major |

Pulls corner of mouth up and lateral |

Score 10-20 |

Mild |

| Buccinator |

Compresses cheek against teeth |

Score 0-10 |

Severe |

| Mentalis |

Depresses lower lip and wrinkles chin

skin

|

Score 0 |

Total |

Chart 1 - Muscle testing of Freyss

16.

Facial nerve palsy can be categorized as complete if there is inability

to voluntarily contract the facial muscles, or incomplete (partial). The

degree of nerve damage can also be assessed by nerve conduction studies

(electromiography-EMG) of the facial nerve. Reduction of the compound

muscle action potential suggests axonal degeneration whereas increase in

latency suggests demyelination of the nerve17.

Facial nerve palsy is an extremely frightening situation for the patient.

The most frequently asked questions by these patients are whether their

facial function will return to normal and how long it will take.

Among the wide variety of available prognostic tests, as discussed by

Hughes18, the EMG seems to be

the most reliable test to predict a patient’s prognosis19. To evaluate the lesion, an EMG

is done early in the post-op, between day 4 and 6, although there is no

rule ordering this first exam, because at this early stage,

electromyography is used to detect any remaining voluntary activity. If

voluntary potentials are detected, the palsy is labeled incomplete. The

paralysis is considered complete only in the case of a totally silent

electromyography19.

A diagnosis according to Sunderland and Seddon classifications (Chart 2) cannot be made at this

stage, because pathologic spontaneous activity as a sign of neural

degeneration does not occur earlier than 10 to 14 days after the onset

of palsy. This early test is mainly intended to categorize the severity

of an individual palsy and does not yield reliable prognostic

information20,21.

Chart 2 - Sunderland and Seddon classifications

21.

| Sunderland |

Seddon |

Injury |

Recovery potential |

| I |

Neurapraxia I |

Disruption of the nerve conduction, but

nerve structure and axon remain intact.

|

Full (Up to 12 weeks) |

| II |

Axonotmesis II |

Disruption of the nerve conduction and

axon degeneration, but remaining nerve structure remains

intact.

|

Full (1mm/day) |

| III |

Axonotmesis II |

Disruption of the endoneurium, but the

perineurium and epineurium remains intact.

|

Full (1mm/day) |

| IV |

Axonotmesis II |

Disruption of the endoneurium and

perineurium, but epineurium remains intact.

|

Poor to none |

| V |

Neurotmesis III |

Total transection of the nerve

fiber.

|

None |

Chart 2 - Sunderland and Seddon classifications

21.

A second examination should be performed not earlier than 10 to 14 days

after the onset of palsy. After this period, all diagnostic criteria may

have developed to establish a diagnosis according to Seddon, which

predicts a prognosis on the expected clinical course19,20.

Steinner published that a fibrillation detected in EMG studies later than

10 to 14 days predicts that a patient has an 80% chance of an

unfavorable result, but on the other hand, the absence of these signs

implies an approximately 93% chance of total recovery20.

Treatment

Eye protection

One of the biggest problems with upper face facial palsy is the

involvement of the eye if the lid commissure remains open. In this

situation, eye care focuses on protection of the cornea from

dehydration, drying or abrasions due to insufficient lid closure or

tears. Eye ointments are recommended during day and night with

protective glasses during the day22.

Physiotherapy

There are only a few controlled trials available on the effectiveness of

physical therapy for facial palsies. In a randomized trial on 50

patients with Bell’s palsy and a House Brackmann scale grade of IV, mime

therapy, speech therapy, including automassage, relaxation exercises,

inhibition of synkinesis, coordination exercises, or emotional

expression exercises, resulted in improvement of facial stiffness, lip

motility, and the physical and social indices of the facial disability

index23. A simple and

reproducible technique has been used and advised by us: the mirror

feedback therapy. It involves training the paralyzed side to reproduce

symmetrical movements of the unaffected side in front of a mirror.

Blanchin et al.24, in 2013,

presented a paper proving that when the mirror therapy is applied to

patients with long standing facial palsy and submitted to Labbe’s

technique of facial reanimation it is more effective in recovering a

spontaneous smile when compared to conventional therapies.

Corticosteroids

Till date to our knowledge, no study has discussed facial nerve trauma

and the use of steroids for treatment. But since it is known that

inflammation (particularly edema) of the facial nerve plays a key role

in the pathogenesis of other types of facial paralysis, such as Bell’s

palsy, we can extrapolate the concept to surgical trauma,. given the

fact that a vast majority of cases are partial lesions.

Corticosteroids have been used due to its powerful anti-inflammatory

effects in Bell’s palsy and this has recently been supported by a

growing and well-designed evidence base. A Cochrane review included 1569

patients from 8 randomized controlled trials of adequate quality, and

showed a benefit in improving the facial recovery, and a significant

reduction in motor synkinesis in the steroid group25. Another high level systematic review published

in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) concluded that

corticosteroids used alone produced a reduced risk of unsatisfactory

recovery26.

Even though the reviews support the use of steroids in facial palsy,

there is no consensus on the prescription pattern. There are many

authors who have suggested different protocols. We recommend the ones

with the largest reviews:

- The Sullivan protocol27:

Prednisolone 25 mg, by mouth (PO), twice daily, for 10 days, starting at

a maximum of 72 h from the onset of palsy.

- The Engström protocol28:

Prednisolone 60 mg PO for 5 days, then the dose is reduced by 10 mg per

day for 5 days, also starting before 72 h of the onset.

- The Lagalla Protocol29:

Prednisone 1 g, intravenous (IV), for 3 days, than 0.5 g IV for 3

days.

- The Stennert protocol (Table 1)30.

Table 1 - Stennert protocol

30.

| Days of

treatment

|

Cortisone (Prednisolone -

equivalent dose - mg/day)

|

Dextran 40 with sorbite or

mannite 5-10%c (ml)

|

Pentoxifylline (Trental)

(ml)

|

| |

<70kg |

|

>70kg |

| In-patient |

1 |

Infusiona |

200 |

|

250 |

500 |

5 |

| |

2 |

|

200 |

|

250 |

500 |

10 |

| |

3 |

|

|

150 |

|

500 |

15 |

| |

4 |

|

|

150 |

|

500 |

15 |

| |

5 |

|

|

100 |

|

500 |

15 |

| |

6 |

|

|

100 |

|

500 |

15 |

| |

7 |

|

|

75 |

|

500 |

15 |

| |

8 |

|

|

50 |

|

500 |

15 |

| |

9 |

Oral

circadianb |

40 |

|

500 |

15 |

| |

10 |

20 |

|

500 |

15 |

| Out-patient |

11 |

(6-8 a.m.) |

15 |

|

|

|

|

| |

12 |

|

12.5 |

|

|

|

|

| |

13 |

|

10 |

|

|

|

|

| |

14 |

|

7.5 |

|

|

|

|

| |

15 |

|

5 |

|

|

|

|

| |

16 |

|

2.5 |

|

|

|

|

| |

17 |

|

2.5 |

|

|

|

|

| |

18 |

|

2.5 |

|

|

|

|

Table 1 - Stennert protocol

30.

Stennert30 proposed a protocol

based on an assumption that nerve damage is caused by edema and primary

and secondary ischemia. To reduce the phlogistic and edematous reaction,

he introduced steroids. Secondly he tried to increase the peripheral

nerve perfusion, by adding pentoxifyline and dextrane to the IV

infusion.

The effect of pentoxifylline on the recovery of Bell’s palsy has only

been tested in association with other drugs, particularly steroids and

low-molecular dextran. The studies showed a beneficial effect of a

combination therapy, but it is not known which of these drugs is

responsible for the beneficial effect16,28.

Botulinum toxin

When injected into facial muscles, botulinum toxin has been found to

reduce the facial asymmetry in patients suffering from facial paralysis

and has being used to treat synkinesis, hyperlacrimation, and

hyperkinesis9. Most people

have neglected the “physiotherapeutic” effect of the toxin. When applied

to the healthy side, the toxin moderates movements, forcing the patient

to exercise the affected side, which helps the muscle recover, and

stimulates new neural connections. Therefore we recommend that it should

be utilized even in the absence of hyperkinesia after confirmation of

the diagnosis, around 12 days after the surgery (assumed facial palsy

onset) and the EMG.

CONCLUSION

There is no consensus on management for a case of accidental nerve injury,

therefore we have proposed a protocol with safe technical options to avoid nerve

damage, identify, and treat if necessary. The proposed protocol is based on our

own experience on treating facial palsy and published studies . Although it

seems difficult to deal with such cases in general, patients with partial nerve

lesions have an excellent prognosis with a recovery rate of 90 to 94%20, especially when the right decisions are

made at the right time. In summary, we present a flowchart to help make clinical

decisions (Figura 5).

Figure 5 - Decision flowchart: Clinical decision making in facial nerve

injuries.

Figure 5 - Decision flowchart: Clinical decision making in facial nerve

injuries.

COLLABORATIONS

|

FSR

|

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study,

data curation, final manuscript approval, methodology, project

administration, supervision, visualization, writing - original draft

preparation, writing - review & editing.

|

|

CMR

|

Data curation, supervision, visualization, writing - review &

editing.

|

|

FV

|

Supervision, writing - review & editing.

|

|

DL

|

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study,

data curation, final manuscript approval, methodology, project

administration, supervision.

|

REFERENCES

1. Castañares S. Facial nerve paralyses coincident with, or subsequent

to, Rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;54(6):637-43.

2. Baker DC, Conley J. Avoiding facial nerve injuries in rhytidectomy.

Anatomical variations and pitfalls. Plast Reconstr Surg.

1979;64(6):781-95.

3. Fattah A, Borschel GH, Manktelow RT, Bezuhly M, Zuker RM. Facial

Palsy and Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2012;129(2):340e-52e.

4. Howard BK, Rohrich RJ. Understanding the nasal airway: principles

and practice. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(3):1128-46.

5. Manktelow RT, Zuker RM, Tomat LR. Facial paralysis measurement with

a handheld ruler. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121(2):435-42.

6. Paletz JL, Manktelow RT, Chaban R. The shape of a normal smile:

implications for facial paralysis reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg.

1994;93(4):784-9.

7. Rubin LR. The anatomy of a smile: its importance in the treatment of

facial paralysis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;53(4):384-7.

8. de Maio M, Bento RF. Botulinum toxin in facial palsy: an effective

treatment for contralateral hyperkinesis. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2007;120(4):917-27.

9. Seckel BR. Facial danger zones: avoiding nerve injury in facial

plastic surgery. 1a ed. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing;

1994.

10. Roostaeian J, Rohrich RJ, Stuzin JM. Anatomical considerations to

prevent facial nerve injury. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2015;135(5):1318-27.

11. May M, Schaitkin BM. The facial nerve. New York: Thieme;

2000.

12. Chatellier A, Labbé D, Salamé E, Bénateau H. Skin reference point

for the zygomatic branch of the facial nerve innervating the orbicularis oculi

muscle (anatomical study). Surg Radiol Anat. 2013;35(3):259-62.

13. Stuzin JM, Wagstrom L, Kawamoto HK, Wolfe SA. Anatomy of the frontal

branch of the facial nerve: the significance of the temporal fat pad. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 1989;83(2):265-71.

14. Dorafshar AH, Borsuk DE, Bojovic B, Brown EN, Manktelow RT, Zuker

RM, et al. Surface anatomy of the middle division of the facial nerve: Zuker’s

point. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(2):253-7.

15. Sameem M, Wood TJ, Bain JR. A systematic review on the use of fibrin

glue for peripheral nerve repair. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2011;127(6):2381-90.

16. Dubreuil C, Charachon R. Clinique: la paralysie faciale

peripherique. In: Charachon R, Bebear JP, Sterkers O, Magnan J, Soudant J, eds.

La paralysie faciale. Le spasme hemifacial. Paris: Société Française

D’oto-Rhino-Laryngologie et de Pathologie Cervico-Faciale / L’européenne

D’éditions; 1997. p. 135-57.

17. Finsterer J. Management of peripheral facial nerve palsy. Eur Arch

Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265(7):743-52.

18. Hughes GB. Prognostic tests in acute facial palsy. Am J Otol.

1989;10(4):304-11.

19. Grosheva M, Wittekindt C, Guntinas-Lichius O. Prognostic value of

electroneurography and electromyography in facial palsy. Laryngoscope.

2008;118(3):394-7.

20. Sittel C, Stennert E. Prognostic value of electromyography in acute

peripheral facial nerve palsy. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22(1):100-4.

21. Chhabra A, Ahlawat S, Belzberg A, Andreseik G. Peripheral nerve

injury grading simplified on MR neurography: As referenced to Seddon and

Sunderland classifications. Indian J Radiol Imaging.

2014;24(3):217-24.

22. Holland NJ, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bell’s palsy. BMJ.

2004;329(7465):553-7.

23. Beurskens CH, Heymans PG. Positive effects of mime therapy on

sequelae of facial paralysis: stiffness, lip mobility, and social and physical

aspects of facial disability. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24(4):677-81.

24. Blanchin T, Martin F, Labbe D. Rééducation des paralysies faciales

après myoplastie d’allongement du muscle temporal. Intérêt du protocole «

effet-miroir ». Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2013;58(6):632-7.

25. Salinas RA, Alvarez G, Daly F, Ferreira J. Corticosteroids for

Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2010;(3):CD001942. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001942.pub4

26. de Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, Witterick IJ, Lin VY,

Nedzelski JM, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell

palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA.

2009;302(9):985-93.

27. Sullivan FM, Swan IR, Donnan PT, Morrison JM, Smith BH, McKinstry B,

et al. Early treatment with prednisolone or acyclovir in Bell’s palsy. N Engl J

Med. 2007;357(16):1598-607.

28. Engström M, Berg T, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, Axelsson S, Pitkäranta

A, Hultcrantz M, et al. Prednisolone and valaciclovir in Bell’s palsy: a

randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol.

2008;7(11):993-1000.

29. Lagalla G, Logullo F, Di Bella P, Provinciali L, Ceravolo MG.

Influence of early high-dose steroid treatment on Bell’s palsy evolution. Neurol

Sci. 2002;23(3):107-12.

30. Stennert E. New concepts in the treatment of Bell’s palsy. In:

Malcolm D, House G, House WF, eds. Disorders of the facial nerve. New York:

Raven Press; 1981. p. 313-8.

1. Clínica Cirurgia Plástica Beauté, Belém, PA,

Brazil.

2. Universidade Estadual de Botucatu, Botucatu,

SP, Brazil.

3. Clínica Particular, Caen, Normandia,

França.

Corresponding author: Franklin de Souza Rocha,

Travessa Dom Romualdo de Seixas 1560, Belém, Brazil. Zip Code: 66055-028.

E-mail: franklinrocha1@hotmail.com

Article received: March 02, 2018.

Article accepted: April 16, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.