INTRODUCTION

Pressure ulcers are alterations of the integrity of the skin and underlying

tissues, caused by pressure, most commonly on the protuberances, especially in

areas deprived of local sensitivity, which lead to necrosis and ulceration.

Data from the international literature estimate that between 3% and 14% of all

hospitalized patients develop pressure ulcers1, which emphasizes the importance of preventive measures in

patients with increased risk. The surgical treatment of pressure ulcers dates

back to 1947, with Croce and Beakes2 using

skin flaps.

The use of muscle and musculocutaneous flaps (proposed by Ger3, Minami et al.4, and Nahai et al.5)

and fasciocutaneous flaps (proposed by Hurwitz et al.6, Alonso et al.7,

Ramirez8, Calil et al.9, and Paletta et al.10) was a significant improvement to the

surgical arsenal for the treatment of these conditions. Within the widely varied

situations that arise in daily clinical practice, surgical solutions with

characteristics appropriate to the patient’s local needs are vital.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to describe the simultaneous correction of extensive sacral and

ischial pressure ulcers with a single flap in a 21-year-old paraplegic patient.

He was admitted with anemia, urinary infection, necrotic ulcers, and spastic

contracture in the lower limbs. After clinical treatment, he was submitted to

correction of the ulcers by rotation of a fasciomyocutaneous flap from the

gluteus maximus and posterior surface of the thigh, pediculated by the superior

and inferior gluteal artery and the posterior fasciocutaneous branch of the

thigh.

In spite of the dimensions, the flap used displayed good blood perfusion,

evolving without necrosis or dehiscence. The flap proved to be a valid option

for young patients without diseases that lead to circulatory impairment.

CASE REPORT

A 21-year-old male patient with a 1-year history of paraplegia received

inadequate care, which led to the development of multiple pressure ulcers,

including extensive right sacral and ischial ulcers. The patient was admitted

febrile, malnourished, anemic, and with urinary tract infection, necrotic

ulcers, and spastic contracture in the lower limbs.

After clinical preparation, simultaneous correction of the right sacral and

ischial ulcers through the rotation of a single fasciomyocutaneous flap was

performed.

Surgical technique

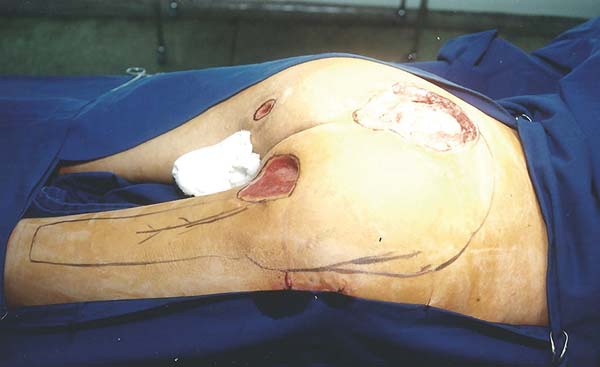

The patient was positioned in ventral decubitus, with the flap and edges of

the ulcers demarcated (Figure 1),

followed by dissection of the flap from the distal extremity while securing

the fascia to the subcutaneous cell tissue (TCSC), elevation of the gluteus

maximus and cutaneous portions (Figure 2), rotation and suturing of the flap closing the two ulcers

(Figure 3), and closing the donor

area of the thigh edge to edge. The flap and donor area evolved with good

healing (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 1 - Demarcation of the flap and edges of the ulcers.

Figure 1 - Demarcation of the flap and edges of the ulcers.

Figure 2 - Intraoperative aspect of the elevated flap.

Figure 2 - Intraoperative aspect of the elevated flap.

Figure 3 - The flap positioned and the donor area with temporary

sutures.

Figure 3 - The flap positioned and the donor area with temporary

sutures.

Figure 4 - Postoperative aspect of the treated sacral ulcer.

Figure 4 - Postoperative aspect of the treated sacral ulcer.

Figure 5 - Postoperative aspect of the treated ischial ulcer. The

treated trochanteric ulcer is also shown.

Figure 5 - Postoperative aspect of the treated ischial ulcer. The

treated trochanteric ulcer is also shown.

RESULTS

The flap used for the simultaneous correction of the right sacral and ischial

ulcers showed good blood perfusion and evolved without necrosis or hematoma. The

patient presented mild superficial pressure sores at the proximal extremity of

the posterior thigh donor area by tension in the suture line, which healed

spontaneously, and presented serous-sanguineous secretion drainage in its

distal end, which did not prevent proper healing. We emphasize that the tension

did not impair the venous return of the right lower limb.

DISCUSSION

According to Alonso et al.7 and Paleta et

al.10, the circulation of the

posterior fasciocutaneous portion of the thigh flap was programed to be

nourished from the fasciocutaneous branch of the inferior gluteal artery. The

anatomical studies of Calil et al.9 showed

an intersection between the first and second perforating branches of the deep

femoral artery, which leads to an extensive area of cutaneous perfusion in the

posterior aspect of the thigh, which allows the preparation of large flaps.

The study of Hurwitz et al.6 showed

inferior gluteal artery anastomoses with branches of the medial femoral

circumflex artery. When these and other anastomotic vessels were sectioned, the

inferior gluteal artery could supply the circulation of the posterior region of

the thigh.

Ramirez8 mentioned the importance of the

first perforating artery for the perfusion of the posterior fasciocutaneous

thigh flap. In two-thirds of flaps in the study, the artery was ligated without

impairment of the flap. The author also mentioned the importance of the branches

of the medial femoral circumflex artery with its more superior and medial

location than the first perforator.

Owing to the arc of rotation of the flap used in the present study and the

inclusion of the gluteus maximus muscle, ligation of the first and second

perforating arteries was needed to maintain the perfusion of the posterior

fasciocutaneous portion of the thigh through the inferior fasciocutaneous

gluteal artery branch. The inclusion of the gluteus maximus muscle in the flap

enabled a better filling of the extensive sacral ulcers.

In the event of necrosis of the fasciocutaneous portion, one option would be to

use the myocutaneous flap of the local gracilis or fasciocutaneous. In sacral

ulcer relapse, a fasciocutaneous flap may be made for closure alone or

associated with a musculocutaneous or fasciocutaneous flap of the contralateral

gluteal region.

CONCLUSIONS

The use of fasciomyocutaneous flaps from the gluteus maximus and posterior

surface of the thigh proved to be a good surgical option for simultaneous

correction of right sacral and ischial ulcers as demonstrated in the case of a

young patient described herein, who had no illnesses that would lead to

circulatory impairment and clinical imbalance.

COLLABORATIONS

|

ACJ

|

Conception and design of the study; execution of the operations

and/or experiments; and drafting and preparation of the original

manuscript.

|

|

RSF

|

Final approval of the manuscript; and drafting; revision; and editing

of the manuscript.

|

REFERENCES

1. Bergstrom N, Allman RM, Alvarez OM, Carlsson CE, Eaglesetein W,

Frantz RA, et al. Pressure ulcer in adults: prediction and prevention.

Rockville: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1992.

2. Croce EJ, Beakes HC. The operative treatment of decubitus ulcer. N

Engl J Med. 1947;237(5):141-9.

3. Ger R. The surgical management of decubitus ulcers by muscle

transposition. Surgery. 1977;69(1);106-10.

4. Minami RT, Mills R, Pardoe R. Gluteus maximus myocutaneous flaps for

repair of pressure sores. Plast Reconstr Surg.

1977;60(2):242-9.

5. Nahai F, Silverton JS, Hill HL, Vasconez LO. The tensor fascia lata

musculocutaneous flap. Ann Plast Surg. 1978;1(4):372-9.

6. Hurwitz DJ, Swartz WM, Mathes SJ. The gluteal thigh flap: a

reliable, sensate flap for the closure of buttock and perineal wounds. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 1981;68(4):521-32.

7. Alonso N, Carramaschi F, Calonge HCF, Gemperli R, Monteiro Júnior

AA, Ferreira MC. Retalho fasciocutâneo posterior da coxa no tratamento de

úlceras de pressão. Rev Bras Ortop. 1986;21(1):13-5.

8. Ramirez OM. The distal gluteus maximus advancement musculocutaneous

flap for coverage of trochanteric pressure sores. Ann Plast Surg.

1987;18(4):295-302.

9. Calil JA, Ferreira LM, Neto MS, Castilho HT, Garcia EB. Aplicação

clínica do retalho fasciocutâneo da região posterior da coxa em V-Y. Rev Assoc

Med Bras. 2001;47(4):311-9.

10. Paletta C, Bartell T, Shahadi S. Applications of the posterior thigh

flap. Ann Plast Surg. 1993;30(1):41-7.

1. Universidade Estadual de Londrina, Londrina,

PR, Brazil.

2. Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR,

Brazil.

Corresponding author: Antonio Chiquetti Junior, Rua Paes Leme, nº

1264, sala 601 - Jardim das Américas - Londrina, PR, Brazil, Zip Code:

86010-610. E-mail: chiqueti@sercomtel.com

Article received: April 12, 2018.

Article accepted: October 1, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.