Original Article - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Formal training in scientific research increases the participation of plastic surgery residents in peer-reviewed articles

O treinamento formal em pesquisa científica aumenta a participação de residentes de Cirurgia Plástica em artigos revisados por pares

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The objectives of this study were as follows: (1)

to outline a scientific research skills training program, (2) to

evaluate the profile of participation of plastic surgery residents

in articles, and (3) to analyze the impact of the implementation

of the training program on quantitative bibliometric indexes.

Methods: This was a bibliometric analysis of the participation

of plastic surgery residents of a single institution in articles

published in peer-reviewed journals between 2006 and 2014.

The data collected were the number of authors, position of

residents among authors, article titles, indexing databases

and impact factor of the journals, study design, and levels of

evidence. Two periods (January 2006 to January 2010 [A] and

February 2010 to February 2014 [B]) were created to study the

evolutionary profile of the impact of the implementation of the

training program outlined in this study.

Results: A significant

predominance (p < 0.05) was observed among articles

published in national journals in the Portuguese language

and in the SciELO and LILACS databases, and articles

without residents as corresponding author, without impact

factor, without assumptions, and with a level of evidence III

(retrospective studies). The inter-period comparative analysis

revealed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in the numbers of

published articles and residents with publications at the

end of their residency, in the involvement of one or more

residents, and in the articles published in English (period A

< period B).

Conclusion: The implementation of a scientific

research skills training program led to an increase in research

activity of (peer-reviewed articles) during the residency.

Keywords: Bibliometrics; Internship and residency; Teaching; Research; Plastic surgery

RESUMO

Introdução: Os objetivos deste estudo foram: (1) delinear um programa de treinamento em

habilidades de pesquisa científica, (2) avaliar o perfil da participação dos

residentes de Cirurgia Plástica em artigos, e (3) analisar o impacto da

implementação do programa de treinamento sobre índices bibliométricos

quantitativos.

Métodos: Trata-se de uma análise bibliométrica da participação de residentes de

Cirurgia Plástica de uma única instituição em artigos publicados em

periódicos revisados por pares entre 2006 e 2014. Dados coletados: número de

autores, posição dos residentes entre os autores, títulos, bases de

indexação e fator de impacto dos periódicos, desenhos dos estudos e níveis

de evidência. Dois períodos (janeiro/2006-janeiro/2010 [A] e

fevereiro/2010-fevereiro/2014 [B]) foram criados para estudar o perfil

evolutivo do impacto da implementação do programa de treinamento delineado

neste estudo.

Resultados: Houve predomínio significativo (p < 0,05) de artigos

publicados em periódicos nacionais, em língua portuguesa, nas bases de dados

SciELO e LILACS, artigos sem residentes como autor correspondente, sem fator

de impacto, sem hipóteses e com nível de evidência III (estudos

retrospectivos). A análise comparativa interperíodos revelou um aumento

significativo (p < 0,05) de artigos publicados, de

residentes com publicações ao término da residência, da participação de um

ou mais residentes e de artigos publicados em inglês (período A < período

B).

Conclusão: A implementação do programa de treinamento em habilidades de pesquisa

científica determinou um aumento da atividade de pesquisa (artigos revisados

por pares) durante a residência.

Palavras-chave: Bibliometria; Internato e residência; Ensino; Pesquisa; Cirurgia plástica

INTRODUCTION

Scientific articles are commonly used for the measurement of individual/institutional performances and to obtain funding1. In the context of plastic surgery, scientific production is one of the main factors that influence the career of newly trained plastic surgeons2 and the selection of candidates into a residency program3. Moreover, the teaching-learning process of multiple elements of scientific research has been considered important in the training of residents4-8.

Nevertheless, insufficient academic activity continues to be a problem common to residency programs4,5. Specifically in Brazil9, 72.2% of plastic surgery residents of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (SBCP) in the Federal District had no article published in the Brazilian Journal of Plastic Surgery (Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica [RBCP]), and the incentive to publish was among the residents’ suggestions for the improvement of evaluated programs. Thus, residency programs should encourage the scientific productivity of their residents to ensure that future goals are achieved4-16.

The participation of residents in scientific production has been assessed mainly in the international context4-8,11-15, and Brazilian data related to the residency in plastic surgery are scarce and regionally limited9,10,16. In addition, the proposals for training programs in scientific research during medical residency have also been restricted to international publications5-8,11,12,17.

OBJECTIVES

The objectives of this study were (1) to outline a training program in scientific research skills, (2) to evaluate the profile of participation of plastic surgery residents in scientific articles, and (3) to analyze the impact of the program on specific quantitative bibliometric indexes.

METHODS

Training program in scientific research skills

In line with the three-fold purpose (assistance, education, and research) of our institution18, at the end of the global training in plastic surgery, residents must also observe, collect, and document data relevant to scientific research, and develop habits of critical reading and scientific update with quality and planning, executing and reporting research by adopting an appropriate scientific methodology.

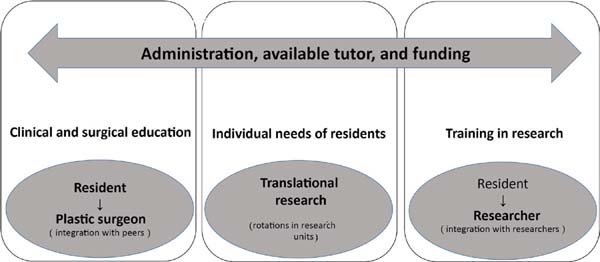

In February 2010, a training program of the foundations of scientific production was implemented in the SOBRAPAR Hospital (Figure 1), following the principles laid down by Mulliken19, which is “teach those who follow—hoping that the young go further.” Although all three essential attributes of a surgeon-scientist (curiosity, imagination, and persistence) reported by Dr. Murray20 may be intrinsic to some, we believe that the incentive for these three qualities to be awakened and developed in training residents is part of the role of all those involved in the residency.

In fact, most residents do not have experience in scientific research and require formal instruction on research4 because without adequate training and motivation, many of them will finish the residency without any knowledge about the scientific process.

As the training in scientific research requires motivation and attention, uninterrupted focus, and repetitive practice with constructive feedback, residents have been encouraged to participate actively in all the stages that make up a research project, always under the supervision of a tutor21 and, if possible, with the support of a resident with research experience8. These residents, generally, with an experience in research, assist in the teaching-learning process of basic research/essential skills (e.g., careful review of the literature, design of methods of analysis, and structuring of complete articles) and guide residents regarding the choice of projects and advisors. Thus, residents with an experience in research have acted as a bridge between the residents with less research experience and the advisors, decreasing the time required for research supervised by tutor surgeons and, consequently, optimizing the scientific production4,5,8.

Our residents have a “protected” time for research, within the base hours, specifically for research (delineate, perform, analyze, present, and publish) without extending the total training time4,5,8,17. Instead of elective or mandatory courses exclusive for research that will potentially reduce their participation in relevant surgical training practice, we prefer the longitudinal distribution of periods during the 3 years of training, with flexibility between the workload for the clinical-surgical training and scientific research, and as a consequence, the knowledge acquired in research is applied daily in clinical-surgical practice (and vice versa)4,5,8,17.

Once a month, a morning (or afternoon) has been devoted exclusively to the scientific part of the training program6,22. In particular, the resident with research experience is responsible for the workshop that explores a series of scientific skills in a didactic-interactive manner. The number and order of the workshops (formulation of hypotheses, design of the studies, data collection, patient selection, critical review of the literature, methods of analysis, statistical techniques, principles of evidence-based medicine, integration of the findings of the survey with the data available in the literature, preparation, paper submission and review, conflicts of interests, and funding sources and mechanisms) are distributed within the grid of the program in accordance with the projects in progress or requests of residents.

Seminars presented by invited researchers, teachers, tutors, and/or residents with research experience complement the period focused on research. In addition to these monthly meetings/workshops, residents meet with advisors and/or residents with research experience in accordance with their individual needs. Thus, many “tips and tricks” useful to write and publish scientific articles can be exchanged between residents, tutors, and advisors throughout this process of teaching and learning.

Completely unjustifiable errors (e.g., plagiarism and manipulation or falsification of data) and the need to anticipate and modify questions related to potential problems of articles (e.g., limitations of the study) have also been the target of teaching because it may increase the efficacy of the residents (“produce more in less time”) and also reduce the odds of frustrations.

In addition, the monthly meetings are also intended for the presentation of projects, abstracts, or full articles developed by the residents, while other residents, interns, tutors, and advisors actively discuss the scientific details in a format of constructive feedback. More specifically, the different scientific skills are acquired and applied in accordance with the stage in which the residents are. At the end of the first year, they are invited to present the initial proposal of their project to the tutors of the institution, and then the design and the viability of the project are evaluated seriously and constructively. From 2 to 4 months later, a reviewed research proposal is presented for final approval; the residents then are encouraged to submit their results in scientific events and then write a first version of the complete article.

It is not our intention to create rivalry or increase competitiveness; in fact, we believe that the residents must not form an integral part of the increased competition present in the academic environment to increase scientific productivity, which can be symbolized by the motto “publish or perish.” Therefore, the requirement is not of a publication per se, but rather of full participation in research projects.

On the other hand, residents with a strong desire to participate in research have been stimulated to produce more projects and, consequently, more articles; however, we take care to ensure that they are not used as “crutches” to increase the overall productivity of the institution. Thus, in our program, the “quality” of the research has been more relevant than the “quantity,” although the completion of one or two research projects and publishing one or two articles in peer-reviewed journals during the residency is a basic objective.

Completing a scientifically sound research project during the residency can be a difficult task and represents a challenge for the residents without prior training in research. As each step of this process (e.g., identifying a research question, formulation of the project, consolidation of the method of analysis, evaluation of the institutional ethics committee, collection and storage of data, and statistical analysis) is subject to unexpected delays and given the relatively short duration of residency, such delays can be discouraging4,5.

Thus, in a training environment with increasingly limited time, such steps should be facilitated, always pondering on the actual attainment of skills and knowledge required in each step of the training. For this reason, some measures (e.g., provide a list of ongoing projects with additional branches or new projects, using established databanks, assist in the submission to the ethics committee, and provide assistance to statistical implementation and interpretation) can accelerate the process, and therefore, increase the participation of residents4,5.

In addition, as a way to reduce the need for funding and complex infrastructures, residents have been encouraged to perform studies based on analysis of medical records or secondary studies (e.g., systematic reviews), or surveys that may be conducted with the resources of the institution.

The basic program described here is flexible and has been adapted in accordance with the needs, new obstacles encountered, and current trends5-8,11,12,17. Furthermore, it is important that during the training, the desires and perceptions of residents (e.g., personal responsibility, focus, idealism, and perseverance) are taken into account.

Thus, along with the global education format designed for all residents, a methodology for individualized teaching-learning may be required to improve individual specific deficits because we recognize that our training program in scientific research does not allow all aspects involved in the “art and science” of writing and publishing scientific articles to be fully taught to all residents during the 3 years of training.

Thus, we have also encouraged residents to learn research skills outside the preset training program (i.e., a self-regulated, deliberate, and repetitive training), for example, with the help of books and articles about the “art and science” of the elaboration of scientific articles.

Bibliometric analysis

A descriptive and quantitative bibliometric analysis23 was performed to characterize the profile of the participation of plastic surgery residents of the SOBRAPAR Hospital in scientific articles published in peer-reviewed journals, between January 2006 and February 2014. To evaluate the impact of the training program on this participation, the global period (2006–2014) was divided into two periods (January 2006 to January 2010 [period A] and February 2010 to February 2014 [period B]), which coincide exactly with the absence and presence of the formal training program, respectively.

Quantitative bibliometric data23 regarding the number of articles, number of authors, position of residents among authors, titles, indexation bases, presence of journal impact factor, language of articles, presence of statistical analysis, presence of hypothesis in the body of the article, study designs, and level of evidence (levels of evidence I to V according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons Evidence Rating Scales16,24) were extracted from each article included by an independent author to avoid inter-rater bias25.

Levels of evidence I and II, and III, IV, and V were classified as high and low levels of evidence, respectively24,25. The weighted average of the level of evidence followed the formula, (percentage of articles by level of evidence ´ level of evidence)/10016,24.

This study followed the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and further amendments and was approved by the local ethics committee (003/2018).

Statistical analysis

As in other studies5-8,10,11, inter-period comparative analyses (A vs B) were particularly performed to characterize the impact of the training program on specific quantitative bibliometric variables. The Mann-Whitney tests, equality of two proportions, and confidence interval for the mean were used for the comparative analyses. For all statistical tests, significance levels of 5% (p < 0.05) and 95% confidence intervals were set.

The data were compiled in Excel 2013 for Windows (Office Home and Student 2013, Microsoft Corporation, USA), and all analyses were performed using the program Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 20 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Numbers of scientific articles and authors

Twenty-two articles were published with the participation of residents between 2006 and 2014, with a mean of 2.75 ± 2.37 (1–6) articles/year. The mean number of published articles was 1.75 ± 2.36 (2–5) and 3.75 ± 2.22 (1–6) articles/year in periods A and B, respectively. Of the residents who completed training in plastic surgery, 50% and 100% had articles published in periods A and B (p < 0.05), respectively.

The inter-period comparative analysis revealed a significant increase (p < 0.05) in the number of published articles, with an increase of 114.28% between periods A and B (Table 1). Five (71.43%) and four published articles (26.67%) in periods A and B (p < 0.05), respectively, had one resident among the authors. Overall and intra-period evaluations revealed a significant (p < 0.05) prevalence of articles without residents as the corresponding author (Table 1).

| Periods | Number of articles n (%) | Number of authors/articles Mean ± SD (V) [Median; Q1-Q3] | Number of residents/articles Mean ± SD(V) [Median; Q1-Q3] | Resident of plastic surgery | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First author (Present/Absent) n (%) | Second author (Present/Absent)n (%) | Corresponding author (Present/Absent) n (%) | ||||

| A | 7 (31.82)* | 6 ± 1.82 (3-9)[6; 5.5-6.5] | 1.86 ± 1.35 (1-4)[1; 1-2.5] | 3 (42.86)/4 (57.14) | 2(40)/5(60) | 2 (28.57)/5 (71.43)** |

| B | 15 (68.18)* | 6.13 ± 2.06 (4-12) [6; 5-7] | 2.53 ± 1.50 (1-6)[2; 1-3.5] | 5 (33.33)/10 (66.67) | 8 (53.33)/7 (46.67) | 0(0)/15(100)** |

| Global | 22(100) | 6.09 ± 1.95 (3-12) [6; 5-7] | 2.32 ± 1.49 (1-6)[2; 1-3.75] | 8 (36.36)/14 (63.64) | 10 (45.45)/12 (54.55) | 2 (9.09)/20 (90.91)*** |

Journals, impact factor, indexing databases, and language

The overall analysis revealed a significant predominance (p < 0.05) of articles published in the RBCP and Brazilian Journal of Craniomaxillofacial Surgery (Revista Brasileira de Craniomaxillofacial Surgery), without an impact factor, in the Scientific Eletronic Library Online (SciELO) e Literatura Latino-americana e do Caribe em Ciências da Saúde (LILACS) databases and in the Portuguese language. The inter-period evaluation revealed a significant increase and reduction (p < 0.05) of articles published in English and Portuguese, respectively.

The intra-period evaluation showed a significant predominance (p < 0.05) of articles published in journals with no impact factor (Table 2). Five articles (33.33%) from period B were published in journals with an impact factor established in the Journal Citation Reports® (JCR; Thomson Reuters) as follows: 3.535 (Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, one article [6.67%]), 1.564 (Aesthetic Surgery Journal, one article [6.67%]), and 0.686 (Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, two articles [13.33%]; Table 2).

| Period | Journal n (%) | IF | Indexing database n (%) | Language of the articles n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RBCP | RBCCM | JCS | Other | (present/absent) n (%) | ISI/Medline | Medline | sciELO | LILACS | Port | Port/Eng | Eng | |

| A | 3(42.86) | 4(57.14) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0)/7(100)¥ | 0(0) | 0(0) | 4(57.14) | 3(42.86) | 7(100)*** | 0(0) | 0(0)# |

| B | 5(33.33) | 4(26.67) | 2(13.33) | 4(26.67) | 4 (26.67)/11 (73.33)¥ | 4(26.67) | 2(13.33) | 4(26.67) | 5(33.33) | 6(40)*** | 3(20) | 6(40)# |

| Global | 8(36.36)* | 8(36.36)* | 2(9.09)* | 4(18.18)* | 4 (18.18)/18 (81.82)¥ | 4(18.18) | 2(9.09)** | 8(36.36)** | 8(36.36)** | 13(59.09)## | 3(13.64)## | 6(27.27)## |

N: Number of articles; RBCP: Brazilian Journal of Plastic Surgery; RBCCM: Brazilian Journal of Craniomaxillofacial Surgery; JCS: Journal of Craniofacial Surgery; Other (1 [4.5%] article/journal), Einstein [Ein], Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery [PRS], Aesthetic Surgery Journal [ASJ], and Plastic Surgery International [PSI]; IF: Impact factor; ISI: ISI Web of Knowledge; Port: Portuguese; Eng: English;

* RBCP = RBCCM > JCS (p = 0.031 for all comparisons, except RBCP vs RBCCM, with p = 1.000) and RBCP = RBCCM> Others individually (Ein/PRS/ASJ/PSI) [p = 0.009 for all comparisons, except for RBCP vs RBCCM, with p = 1.000];

** LILACS = SciELO > Medline (p = 0.031 for all comparisons, except LILACS vs. SciELO, with p = 1.000);

*** p = 0.050;

# p = 0.008;

## Port > Port/Eng = Eng (p = 0.002 for Port vs. Port/Eng, p = 0.033 for Port vs English, and p = 0.262 for Port/Eng vs Eng);

¥ Absent > Present in the global and intra-period analysis;

Statistical analysis, assumptions, study design, and level of evidence

Global and intra-period comparisons revealed a significant predominance (p < 0.05) of articles without assumptions, retrospective studies, and level of evidence III (Table 3). The global weighted average level of evidence was 3.05. The weighted average of the level of evidence were 2.86 and 3.13 in periods A and B (p = 0.532), respectively.

| Periods | Statistical analysis (Present/Absent) n (%) | Hypotheses* (Present/Absent) n (%) | Study designn (%) | Level of evidence* n (%) | Level ofevidence (weighted average) Mean ± SD | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prospective | Retrospective | Case Report | I | II | III | IV | V | (Median; Q1-Q3) | |||

| A | 4(57.14)/3(42.86) | 0(0)/7(100) | 1(14.29) | 6(85.71) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(14.29) | 6(85.71) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 2.86 ± 0.38 (3; 3-3) |

| B | 8(53.33)/7(46.67) | 5(33.33)/10(66.67) | 2(13.33) | 11(73.33) | 2(13.33) | 0(0) | 2(13.33) | 11(73.33) | 0(0) | 2(13.33) | 3.13 ± 0.83 (3; 3-3) |

| Global | 12(54.55)/10(45.45) | 5(22.73)/17(77.27) | 3(13.64) | 17(77.27) | 2(9.09) | 0(0) | 3(13.64) | 17(77.27) | 0(0) | 2(9.09) | 3.05 ± 0.72 (3; 3-3) |

N: number of articles; M: Mean; SD: Standard deviation; Q1: First quartile (distribution until 25% of the sample); Q3: Third quartile (shows the distribution until 75% of the sample); *Absent > Present in global and intra-period comparisons (p < 0.001); *Retrospective > Prospective = Case Reports (p < 0.001 for all comparisons and intra-period [global and intra-period], except Prospective vs Case reports, with p = 0.635); ***III > II = V (p < 0.001 for all comparisons [Global and intra-period], except II vs. V, with p = 0.635); p > 0.05 for all other comparisons.

A significant predominance (p < 0.05) was observed among the articles with a low level of evidence (86.36%, 85.71%, and 86.67% of the articles had level of evidence III or V in the overall period, periods A and B, respectively) when compared with articles of a high level of evidence (13.64%, 14.29%, and 13.33% of the articles presented level of evidence II in the overall period, period A, and period B, respectively; Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Participation in scientific research has been considered a vital component for the growth and development of residents in training4-8-12,16,17,26-28. Accordingly, one group27 reported that the training programs in plastic surgery in Canada need to do more than just encourage residents to participate in scientific research activities and must also find solutions to problems (funding, protected time, and support from mentors/advisors).

We also place participation in research among the basic needs of residents in training. However, like numerous authors5-8,11,12,17,27, we believe that before (or together with) the obligation of publication, curricular, structural, and support modifications should be well established.

Although 66.7% of the Brazilian plastic surgery residents evaluated in a recent study9 presented abstracts in SBCP events, only 27.8% of them had works published in the RBCP. It is important that residents should apply the thinking of Dr. Murray, which is “The abstract is just a work in progress”22.

We have taught and encouraged residents to publish abstracts presented in scientific events as full articles, as this allows for the consolidation of the quality and validity of scientific research and expands the dissemination of information and makes it lasting22. As demonstrated in previous studies5,7,13, our research training program resulted in significant increases in the total numbers of published articles and articles with more than one resident among the authors.

In the specific context of residency, the order of appearance of the authors in scientific articles is a relevant aspect. We have consistently taught and encouraged residents on the criteria of authorship (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors), including the principle that those who had purely technical input (surgical procedure, slide analysis, head of department/service or funding) should not be listed among the authors.

However, we realize that young authors-residents tend to erroneously adopt “given authorship” by placing the names of those who did not substantially participate in the design, drafting, or revision of the article. This is usually done by feeling “pressured” just to maintain good interpersonal relationships and/or because resident authors often do not have minimal knowledge about the rules governing scientific authorship29.

In addition, as residents may feel uncomfortable in questioning authorship, honesty, trust, fairness, professionalism, and academic integrity disputes, for having limited (or absent) research experience and are in “vulnerable positions”29, they can easily be “removed” from the first position. In fact, greed and lack of sincerity of authors with more research experience can frequently sabotage any efforts put into an honest and authentic setting of the order of appearance of the authors29.

To avoid this potentially hostile bias towards the author-resident, we rigorously adopted the authorship criteria based on scientific merit (“the laurels of victory to all those who truly deserve”) and revealed no significant predominance in the proportion of articles without residents as first or second author, which is in accordance with the trends found in similar studies5,11,14.

In this context, Mulliken19 defined that “the first author is the one who does the work and writes the first draft—even if he does not know what he is talking about.” However, we believe that this concept does not apply completely to the Brazilian scenario. In the United States, the residents are encouraged to publish during the entire medical training and only those with satisfactory academic productions have reached top rankings in the selection processes of plastic surgery training programs3.

In contrast to this condition, as a rule, the training programs in Brazilian plastic surgery select the “best” residents through a process based mainly (90% of the potential final grade) on an exclusively theoretical or theoretical-practical (minority of services) evaluation of their global and specific medical knowledge, partially ignoring scientific production.

In fact, the background of research of candidates have been investigated in the framework of the global curriculum analysis (10% of the final potential grade), and the criteria established often do not follow any standards of measurement of scientific production adopted in the academic world. Thus, medical students and residents of Brazilian general surgery end up not identifying any direct advantages in focusing their efforts on the participation in scientific research. In addition, they can use “shortcuts” to achieve good grades in curriculum analysis, such as presenting numerous abstracts at scientific events rather than producing a single full article.

In this context, unlike the proposal by Mulliken19, we believe that the first version of the article usually does not mean anything, especially when little effort was used in its elaboration (e.g., absence of correct and detailed literature review). It is not uncommon to note that the main objective of the resident is, in fact, completing the article without worrying about the “quality” presented.

Therefore, in our institution, the order of the authors of an article involving prospective data has been discussed and defined before the organizing and writing process, and specific authorship criteria (longitudinal collection of data, careful analysis of the pertinent literature, creation of hypotheses to improve the surgical techniques and patient care, organization of ideas, and writing with “quality”) have been adopted particularly in those articles.

Furthermore, a tutor/mentor should “reward” the student/resident with the first position of an important article in which merit stands out because residents are still in training and a “reward” based on their attitudes (perseverance and dedication) can motivate them to go forward.

All these aspects have been detailed in the beginning of the teaching-learning process; with all this in mind, residents may take into account if participation in the project will be rewarding and meaningful for their training. We hope that this authorship normalization can serve as a stimulus for the resident to participate in future academic projects and act as a motivator to beginner residents who may also want to be among the authors of an article, and therefore, have to pass through many stages of the teaching and learning process until acquiring the necessary research skills.

The weight of clinical and surgical training (requirements established by the National Commission of Medical Residency of the Ministry of Education [CNRM/MEC], Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery [SBCP], and services accredited by the SBCP) and scientific training (research method, knowledge of computer science, statistics, review and interpretation of the literature, academic issues, ethical issues, criteria for authorship and scientific contributions, elaboration of complete articles, and peer review process, among others) should be balanced, and the obligations and requirements should vary according to the year of training of the plastic surgery resident.

The overlap between the three main purposes (Figure 1) creates additional needs and requirements, including developing the identities of plastic surgery residents as researchers and plastic surgeons (integration with peers, including researchers and non-researchers as residents, plastic surgeons, practitioners of other medical areas, and other health professionals) and rotations in other settings (regardless of area).

This program should be dynamic and flexible and should be continually revised and updated according to the changes and needs of the plastic surgery residents, with the requirements laid down by the bodies that regulate medical residency programs and following global scientific trends.

Future studies should incorporate the training of those responsible for the education of residents and test this aspect as a potential variable for improving the teaching-learning process of research skills.

Furthermore, the research performed by residents has the potential to contribute to the academic growth of the field of plastic surgery, including efforts to increase the overall level of evidence published by the community of plastic surgeons16,24,25.

For this reason, besides the educational measures described herein, the garnering of financial aid for complex projects and modifications at national level in aspects such as extensive curricular changes16,24 and transformations in the selection process (e.g., increasing the emphasis in the research experience, including peer-reviewed publications, with the adoption of internationally used score scales15) depend on a joint initiative between the different Brazilian organs (CNRM/MEC, SBCP, CNPq, among others).

As more residents acquire scientific competencies and develop a passion for the “art and science” of scientific research27, a new generation of academic plastic surgeons will emerge in the coming years, as reported in other medical fields5,7,13.

CONCLUSIONS

This study outlined a training program in scientific research, presented a bibliometric profile of participation of plastic surgery residents in published scientific articles, and demonstrated that the implementation of the program increased research activity during the residency.

COLLABORATIONS

|

RD |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analysis; final approval of the manuscript; data collection; conception and design of the study; project management; methodology; completion of operations and/or experiments; and writing of the original manuscript. |

|

CARA |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; and review and editing of the manuscript. |

|

EG |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; and review and editing of the manuscript. |

|

CLB |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; writing - review and editing. |

|

CERA |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; methodology; and review and editing of the manuscript. |

REFERENCES

1. Barreto ML. The challenge of assessing the impact of science beyond bibliometrics. Rev Saúde Pública. 2013;47(4):834-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0034-8910.2013047005073

2. DeLong MR, Hughes DB, Tandon VJ, Choi BD, Zenn MR. Factors influencing fellowship selection, career trajectory, and academic productivity among plastic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(3):730-6. PMID: 24572862

3. Nagarkar P, Pulikkottil B, Patel A, Rohrich RJ. So you want to become a plastic surgeon? What you need to do and know to get into a plastic surgery residency. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(2):419-22.

4. Rothberg MB. Overcoming the obstacles to research during residency: what does it take? JAMA. 2012;308(21):2191-2.

5. Rothberg MB, Kleppel R, Friderici JL, Hinchey K. Implementing a resident research program to overcome barriers to resident research. Acad Med. 2014;89(8):1133-9.

6. Basu Ray I, Henry TL, Davis W, Alam J, Amedee RG, Pinsky WW. Consolidated academic and research exposition: a pilot study of an innovative education method to increase residents' research involvement. Ochsner J. 2012;12(4):367-72.

7. Panchal AR, Denninghoff KR, Munger B, Keim SM. Scholar quest: a residency research program aligned with faculty goals. West J Emerg Med. 2014;15(3):299-305. PMID: 24868308

8. Lennon RP, Oberhofer AL, McNair V, Keck JW. Curriculum changes to increase research in a family medicine residency program. Fam Med. 2014;46(4):294-8.

9. Batista KT, Pacheco LMS, Silva LM. Evaluation of plastic surgery residency programs in Distrito Federal. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(1):20-8.

10. Arruda FCF, Paula PRS. Publicação dos residentes de cirurgia plástica em serviços credenciados - análise comparativa de 10 anos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(3):398-402.

11. Manring MM, Panzo JA, Mayerson JL. A framework for improving resident research participation and scholarly output. J Surg Educ. 2014;71(1):8-13. PMID: 24411416

12. Wagner RF Jr, Raimer SS, Kelly BC. Incorporating resident research into the dermatology residency program. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2013;4:77-81.

13. Ahmad S, De Oliveira GS Jr, McCarthy RJ. Status of anesthesiology resident research education in the United States: structured education programs increase resident research productivity. Anesth Analg. 2013;116(1):205-10. PMID: 23223116

14. Morgan PB, Sopka DM, Kathpal M, Haynes JC, Lally BE, Li L. First author research productivity of United States radiation oncology residents: 2002-2007. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;74(5):1567-72.

15. Emerick T, Metro D, Patel R, Sakai T. Scholarly activity points: a new tool to evaluate resident scholarly productivity. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(3):468-76.

16. Denadai R, Raposo-Amaral CE. Levels of evidence in plastic surgery: an analysis of resident involvement. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(4):1573-5.

17. Arbuckle MR, Gordon JA, Pincus HA, Oquendo MA. Bridging the gap: supporting translational research careers through an integrated research track within residency training. Acad Med. 2013;88(6):759-65.

18. Raposo-Amaral CE, Raposo-Amaral CA. Changing face of cleft care: specialized centers in developing countries. J Craniofac Surg. 2012;23(1):206-9.

19. Mulliken JB. The molders of this plastic surgeon and his quest for symmetry. J Craniofac Surg. 2004;15(6):898-908.

20. Mulliken JB. Sense of wonder. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20(Suppl 1):603-7.

21. Franzblau LE, Kotsis SV, Chung KC. Mentorship: concepts and application to plastic surgery training programs. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(5):837e-43e. PMID: 23629123

22. Smart RJ, Susarla SM, Kaban LB, Dodson TB. Factors associated with converting scientific abstracts to published manuscripts. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24(1):66-70.

23. Durieux V, Gevenois PA. Bibliometric indicators: quality measurements of scientific publication. Radiology. 2010;255(2):342-51. PMID: 20413749

24. Denadai R, Raposo-Amaral CE. The level of evidence published in a partner Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):242e-4e. PMID: 24469216

25. Chuback JE, Yarascavitch BA, Eaves F 3rd, Thoma A, Bhandari M. Evidence in the aesthetic surgical literature over the past decade: how far have we come? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(1):126e-34e.

26. Rohrich RJ, Robinson JB Jr, Adams WP Jr. The plastic surgery research fellow: revitalizing an important asset. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(3):895-8. PMID: 9727462

27. Ferron CE, Lemaine V, Leblanc B, Nikolis A, Brutus JP. Recent Canadian plastic surgery graduates: are they prepared for the real world? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):1031-6. PMID: 20195130

28. Mayer HF. Post-graduate training in plastic surgery at the department of Professor Ivo Pitanguy: a report. Int Surg. 2003;88(1):55-8.

29. Bavdekar SB. Authorship issues. Lung India. 2012;29(1):76-80.

1. Hospital SOBRAPAR, Instituto de Cirurgia

Plástica Craniofacial, Campinas, SP, Brazil.

2. Faculdade de Ciências Médicas, Universidade

Estadual de Campinas, Departamento de Neurologia, Campinas, SP,

Brazil.

Corresponding author: Rafael Denadai, Av. Adolpho Lutz, 100 - Cidade Universitária - Campinas, SP, Brazil, Zip Code 13083-880. E-mail: denadai.rafael@hotmail.com

Article received: July 20, 2018.

Article accepted: November 11, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter