INTRODUCTION

Obesity is a serious disease usually associated with increased morbidity and

mortality, increased healthcare costs, reduced quality of life, and reduced life

expectancy1.

The clinical management of obesity is challenging because most individuals with

morbid obesity cannot lose or maintain the lost weight2.

In recent years, the surgical treatment of morbid obesity has gained popularity.

The effectiveness of surgical treatment in weight loss has been confirmed by

well-controlled studies, especially in the United States and Sweden3,4. In the United States, the number of surgical procedures for

weight loss increased from 28,800 in 1999 to 220,000 in 20094.

Safety in the execution of bariatric surgery, represented by low rates of early

and late complications (venous thromboembolism, surgical reintervention, and

prolonged hospitalization) and a mortality rate of 0.3%, together with a

significant decrease in comorbidities, justify the inclusion of bariatric

surgery as an essential strategy for treating morbid obesity1,5.

Patients who undergo gastric bypass surgery usually complain of excess skin and

loss of soft tissues, which affect the practice of exercises and suitability of

clothes, and may lead to aesthetic, posture, and mobility problems. In addition,

weight loss may result in pain due to mechanical friction, limit hygiene

procedures, and cause fungal infections and intertriginous dermatitis6.

Post-bariatric surgery patients who intend to undergo abdominoplasty (AP) should

be carefully monitored for the risk of postoperative complications because these

patients usually present with residual comorbidities, nutritional deficiencies,

and psychological problems7.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to assess the anthropometric profile, and the

prevalence of comorbidities and complications in patients who underwent AP after

vertical-banded gastroplasty-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (VBG-RYGB).

METHOD

This prospective study was conducted in a public referral hospital for bariatric

surgery. The sample included individuals who underwent vertical-banded

gastroplasty-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (VBG-RYGB) followed by AP from

2011 to 2016 after massive weight loss.

This study was performed in accordance with the National Health Council

Resolution No. 466 of 12/12/2012. All the participants were informed about the

scope of the study and signed a free and informed consent form. The authors of

the present study no conflicts of interest to declare. The study was approved by

the research ethics committee of the Health Department of the Federal District

under Certificate for Ethics Assessment (Certificado de Apresentação para

Apreciação Ética-CAAE) No. 52738216.5.0000.5553 (Opinion No. 1,504,199).

All the surgeries were performed by the same team of assistants at the Regional

Hospital of Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for AP after VBG-RYGB were weight stability for at

least 6 months after achieving the weight loss goal in each case, absence of

drug and alcohol abuse, absence of moderate or severe psychotic or dementia,

and acknowledgment of the need for weight maintenance and postoperative

follow-up by a multidisciplinary team1,8.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were smoking, gestational intention, weight

instability and absence of maintenance of weight for 6 months, not signing

the consent form, patients who underwent other bariatric procedures after

VBG-RYGB, patients followed up for <12 months, and patients belonging to

vulnerable groups (mentally ill, institutionalized, or aged <18

years)8.

Analyzed variables

The analyzed variables were age, sex, weight, height, body mass index (BMI)

before VBG-RYGB (kg/m2), BMI before AP (kg/m2), total

weight loss (%), percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL), time interval

between VBG-RYGB and AP (months), presence of comorbidities before VBG-RYGB,

presence of comorbidities before AP, number of medications used before and

after VBG-RYGB, and postoperative complication rate.

Anthropometric variables

Weight was measured on a digital scale with a maximum capacity of 300 kg.

Height was determined using a Personal Caprice Sanny®

stadiometer. %EWL was obtained using the following formula: weight loss

after AP/excess weight × 100. Excess weight was calculated by subtracting

the weight at the beginning of the VBG-RYGB follow-up from the ideal weight

(BMI of 25 kg/m2)9.

The BMI variation (ΔBMI) was calculated as the difference between the maximum

BMI before VBG-RYGB and the BMI at the time of AP.

Clinical variables and comorbidities

The diagnoses of systemic arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, type 2

diabetes mellitus, and metabolic syndrome were based on parameters

established in the respective guidelines of the Brazilian Society of

Cardiology and currently described in the First Brazilian Guideline for the

Diagnosis and Treatment of Metabolic Syndrome10. Hepatic steatosis was diagnosed using preoperative abdominal

ultrasonography.

The preoperative diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea was based on the

apnea-hypopnea index (AHI). An apnea event was defined as cessation of

oronasal airflow for ≥10 seconds. A hypopnea event was defined as a

reduction in nasal pressure signal of ≥30% accompanied by desaturation of

≥4% for >10 seconds.

The AHI was defined as the sum of apnea and hypopnea events per hour of

sleep. The diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea was based on an AHI of ≥5.0

events per hour, and the severity of obstructive sleep apnea was based on

the following AHI scores: mild (5.0 to 14.9 events/hour), moderate (15.0 to

29.9 events/hour), or severe (≥30.0 events/hour)11.

Patients with arthropathy were defined as those who underwent surgical

treatment for joint pain or received conventional anti-inflammatory drugs as

treatment for joint pain9.

Number of medications for treatment of comorbidities

After VBG-RYGB, comorbidities were considered resolved in cases in which they

were controlled without medications and considered improved when they were

controlled using smaller doses. The number of medications taken by the

patient before VBG-RYGB and the number of drugs the patient continued taking

after the surgery were calculated. The drugs were categorized by classes as

follows: antihypertensive, hypoglycemic, anti-inflammatory, cholesterol

reducers, bronchodilators, multivitamins, anxiolytics, and

antidepressants12.

Abdominoplasty

AP involved the removal of excess skin and abdominal fat combined with an

extensive detachment of the upper abdominal flap, correction of the

diastasis of the rectus abdominis, and umbilical transposition. Anchor-line

AP included a vertical midline resection and was usually required in

patients with previous midline scars and incisional hernias, and patients

with excess vertical and horizontal abdominal dermis and panniculus13,14.

Postoperative complications

The evaluated complications were hematomas, seromas, dehiscence, tissue

necrosis, internal hernias, deep venous thromboembolism, and pulmonary

embolism. The complications were divided into major and minor. Major

complications were considered as those requiring a new surgical procedure

for hematoma drainage, seroma drainage, dehiscence suture, or

rehospitalization for systemic antibiotic therapy.

The epidemiological, anthropometric, clinical, and surgical variables were

compared between the patients with and without postoperative complications.

This strategy allowed determining the factors associated with complications

in VBG-RYGB patients undergoing AP15-18.

Postoperative care

All the patients received non-drug thromboembolic prophylaxis, including

early ambulation and lower limb compression. Cystoscopic surveillance was

performed, the bladder catheter was removed on the first postoperative day,

and prophylactic antibiotic therapy was initiated. Anesthetic induction was

performed using 2 g of intravenous cefazolin.

Elastic compression stockings were routinely used for 3 months. The vacuum

drains used in AP were removed on the seventh day regardless of the flow

rate.

The patients were hospitalized until the following day and maintained a

semi-Fowler position, with an indwelling urinary catheter and stimulation of

the active movements of the feet and knees.

The basic guidelines were maintaining the elastic compressive stockings,

increasing water intake, walking, and avoiding physical exertion. The

postoperative visits were weekly in the first month and then monthly for a

minimum of 12 months.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social

Sciences (SPSS) statistical package 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL,

USA). Continuous variables were described using means and standard

deviations, and categorical variables were described using relative

frequencies. The normality of the variables was evaluated using the

Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. All analyses were performed at a level of

significance of 5%.

The groups were compared using the chi-square test for dichotomous variables,

the Student t-test for continuous variables with a normal

distribution, and the Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous

variables with a non-normal distribution. The correlations between

continuous variables were assessed using the Spearman correlation

coefficient (rs).

RESULTS

A total of 107 patients underwent operation after VBG-RYGB using videolaparoscopy

(60; 55.8%) or laparotomy (47; 44.2%). The mean age was 40.89 ±9.76 years, and

most surgeries (91.6%, 98/107) were performed on women.

Anthropometric variables

The anthropometric profile of the VBG-RYGB patients before undergoing AP are

shown in Table 1.

Table 1 - Anthropometric profile of the post-bariatric surgery patients

before abdominoplasty at the Asa Norte Regional Hospital, Brasília,

Federal District, Brazil, from 2011 to 2016.

| Characteristics |

Mean |

SD*** |

| Age (years) |

40.89 |

9.76 |

| Maximum weight (kg) |

120.79 |

24.19 |

| Maximum BMI* (kg/m2)

|

45.52 |

7.55 |

| Final BMI before abdominoplasty

(kg/m2)

|

27.63 |

3.70 |

| Total weight loss (kg) |

47.70 |

17.32 |

| %EWL** |

78.79 |

12.61 |

Table 1 - Anthropometric profile of the post-bariatric surgery patients

before abdominoplasty at the Asa Norte Regional Hospital, Brasília,

Federal District, Brazil, from 2011 to 2016.

The patients who underwent VBG-RYGB usually had morbid obesity or grade II

obesity, and these two groups represented 100% of the sample (Table 2). The patients who underwent AP

after VBG-RYGB usually presented overweight or normal BMI, and both groups

represented 75.6% of the sample.

Table 2 - Distribution of patients according to the degree of obesity (BMI

before bariatric surgery and abdominoplasty) after undergoing

bariatric surgery at the Regional Hospital of Asa Norte, Brasília,

Federal District, Brazil, from 2011 to 2016.

| BMI (kg/m2)

|

Before bariatric surgery, number of patients

(%)

|

Before abdominoplasty, number of patients

(%)

|

| <25 (normal) |

0 |

21 (19.6%) |

| 25.0–29.9 (overweight) |

0 |

60 (56.1%) |

| 30.0–4.9 (grade I) |

0 |

24 (22.4%) |

| 35.0–39.9 (grade II) |

22 (20.6%) |

1 (0.9%) |

| >40.0 (grade III) |

85 (79.9%) |

1 (0.9%) |

Table 2 - Distribution of patients according to the degree of obesity (BMI

before bariatric surgery and abdominoplasty) after undergoing

bariatric surgery at the Regional Hospital of Asa Norte, Brasília,

Federal District, Brazil, from 2011 to 2016.

The difference between the maximum BMI before VBG-RYGB and before AP (ΔBMI)

was 18.60 ± 9.34 kg. Moreover, 33.6% (36/107) of the patients presented a

BMI variation of >20 kg/m2, and 36.4% (39/107) had a weight

loss of ≥50 kg.

Clinical variables and comorbidities

The diseases diagnosed before VBG-RYGB are shown in Table 3. The most common comorbidities were metabolic

syndrome, arterial hypertension, arthropathy, depression/anxiety, and

diabetes mellitus. The least common comorbidities were obstructive sleep

apnea syndrome, esophagitis, and dyslipidemia.

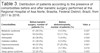

Table 3 - Distribution of patients according to the presence of

comorbidities before and after bariatric surgery performed at the

Regional Hospital of Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil,

from 2011 to 2016.

| Comorbidities |

Before bariatric surgery, number of patients

(%)

|

Before abdominoplasty, number of patients

(%)

|

Valor p |

| Metabolic syndrome |

61 (56.5%) |

6 (5.6%) |

0.027 |

| Hypertension |

59 (54.6%) |

12 (11.1%) |

0.001 |

| Arthropathy |

42 (38.9%) |

5 (4.6%) |

0.004 |

| Diabetes mellitus |

41 (38.0%) |

6 (5.6%) |

0.002 |

| Depression/anxiety |

40 (37.0%) |

27 (25.0%) |

0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia |

26 (24.1%) |

2 (1.9%) |

0.010 |

| Sleep apnea syndrome |

22 (20.4%) |

2 (1.9%) |

0.005 |

| Esophagitis |

22 (20.4%) |

4 (3.8%) |

0.005 |

Table 3 - Distribution of patients according to the presence of

comorbidities before and after bariatric surgery performed at the

Regional Hospital of Asa Norte, Brasília, Federal District, Brazil,

from 2011 to 2016.

Most patients reported improvement or complete resolution of many of these

comorbidities after surgical treatment of obesity. However, some patients

had preexisting diseases before undergoing AP, with depression and anxiety

and hypertension being the most frequent (Table 3). In addition, 35.2% (38/107) of the patients had

undergone cholecystectomy before AP.

Number of medications for treatment of comorbidities

The mean daily number of medications taken by the patients before VBG-RYGB

was 4.24 ± 3.25, which decreased to 1.74 ± 1.31 after VBG-RYGB. This

difference was significant (p < 0.001, 95% confidence

interval [CI], 3.62-4.86).

AP: time interval after VBG-RYGB, combined surgeries, and complication

rates

The mean time between VBG-RYGB and AP was 43.47 ± 29.82 months. The patients

underwent AP more frequently at 25-48 months and 18-24 months after

VBG-RYGB, and these time intervals represented 70.6% of the sample.

The adopted techniques were classical (80; 74.8%) and anchor-line (27;

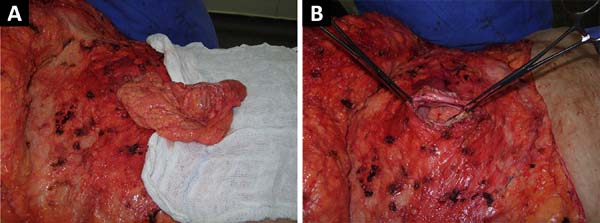

25.2%). Incisional hernias occurred in six patients; and umbilical hernia,

in eight patients, representing 13.1% of patients undergoing AP.

Herniorrhaphy was performed during AP (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - A post-bariatric surgery patient who underwent incisional

herniorrhaphy during abdominoplasty.

Figure 1 - A post-bariatric surgery patient who underwent incisional

herniorrhaphy during abdominoplasty.

Ninety-one patients (85.0%) underwent only one surgical procedure per stage,

and 16 (14.9%) underwent combined surgeries in the same surgical procedure.

The other associated surgical procedures were mastoplasty (12 patients) and

brachioplasty (four patients).

The overall complication rate was 31.5% (34/107). The rate of major

complications was 11.1% (12 patients), including wound dehiscence requiring

resuturing (four cases), hematoma/seroma requiring reoperation (three

cases), internal hernia with intestinal obstruction (three cases), and wound

infection requiring treatment with intravenous antibiotics (two cases).

The rate of minor complications was 20.4% (22 patients), including seroma

requiring repeated punctures (nine cases), hematoma with drainage or

spontaneous resolution (five cases), dehiscence not requiring resuturing

(five cases), and wound infection requiring treatment with oral antibiotics

(three cases).

The mean surgical time was 170.00 ± 55.33 min. Vacuum drains were used in all

the AP procedures.

General anesthesia was used in 95 patients (88.8%), and epidural anesthesia

was used in 12 patients (11.2%).

The mean length of hospital stay was 2.0 ± 1.2 days, and a period of

hospitalization of 2 days was necessary in 98 hospitalizations (91.6%). Only

nine patients (8.4%) required hospitalization for >2 days.

The patients were followed up for at least 12 months. No case of deep venous

thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, or death was found in our sample.

Factors associated with complications in AP in the VBG-RYGB

patients

The age-related and anthropometric factors associated with complications in

AP in the VBG-RYGB patients are shown in Table 4. The factors more strongly associated with postoperative

complications in these patients were age of >40 years, pre-VBG-RYGB

maximum weight, pre-VBG-RYGB BMI, ΔBMI, total weight loss, and BMI variation

(ΔBMI) of >20 kg/m2. Pre-AP BMI and weight loss of >50 kg

were not significantly higher in the VBG-RYGB patients who presented

complications after AP (p < 0.08).

Table 4 - Age and anthropometric factors that potentially led to the

complications in the post-bariatric surgery patients who underwent

abdominoplasty.

| Variables |

Presence of complications |

Absence of complications |

p-value

|

OR |

95% CI |

| Patients (N) |

34 |

73 |

- |

- |

- |

| Age (years)a |

43.09 ± 12.1 |

39.9 ± 8.4 |

0.058 |

- |

- |

| Age >40 years |

73.5% |

47.3 |

0.011*** |

2.22 |

[1.15-4.30] |

| Mean maximum weight before bariatric surgery

(kg)a

|

129.4 ± 30.6 |

116.5 ± 19.5 |

0.010*** |

- |

- |

| Maximum BMI before bariatric surgery

(kg/m2)a |

48.5 ± 9.6 |

44.1 ± 5.9 |

0.004*** |

- |

- |

| Mean BMI before abdominoplasty

(kg/m2)a |

28.5 ± 4.4 |

27.2 ± 3.3 |

0.094 |

- |

- |

| Mean ΔBMI (kg/m2)a |

19.7 ± 7.5 |

16.9 ± 4.9 |

0.022*** |

- |

- |

| Total weight loss (kg)a |

54.5 ± 23.1 |

44.3 ± 12.9 |

0.004*** |

- |

- |

| Lost weight ≥50 kg |

50.1% |

31.0% |

0.059 |

1.70 |

[0.98;2.94] |

| ΔBMI > 20 kg/m2 |

47.0% |

27.0% |

0.040*** |

1.78 |

[1.03;3.06] |

| BMI before abdominoplasty > 30

kg/m2 |

24.32% |

21.57% |

0.818 |

- |

- |

Table 4 - Age and anthropometric factors that potentially led to the

complications in the post-bariatric surgery patients who underwent

abdominoplasty.

The factors associated with complications after AP related to comorbidities

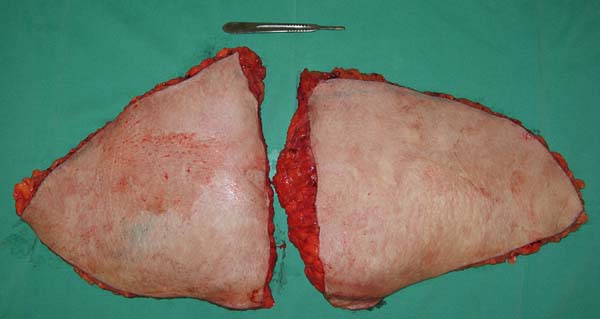

and weight of the abdominal flap removed during AP are shown in Table 5. The factors significantly

associated with postoperative complications in these patients were the

presence of comorbidities (dyslipidemia, diabetes, and arterial

hypertension), weight of the excised flap, especially when weight was

>2,000 g (Figure 2).

Table 5 - Other factors that potentially led to the complications in the

post-bariatric surgery patients who underwent

abdominoplasty.

| Variables |

Presence of complications |

Absence of complications |

p-value

|

OR |

95% CI |

| Weight of the flap removed from the abdomen

(g)a |

2743 ± 1601 |

1630.1 ± 846 |

<0.001*** |

- |

- |

| Weight of the removed flap of ≥2,000

g*

|

61.8% |

25.7% |

0.004*** |

3.41 |

[2.11; 5.56] |

| Diabetes |

11.8% |

2.7% |

0.056 |

2.27 |

[1.19;4.30] |

| Hypertension |

17.7% |

8.1% |

0.143 |

1.71 |

[0.90;3.27] |

| Dyslipidemia |

5.9% |

0.0% |

0.035*** |

3.31 |

[2.48;4.42] |

| Metabolic syndrome |

11.8% |

2.7% |

0.056 |

2.27 |

[1.19-4.30] |

| Diabetes/hypertension** |

26.5% |

8.1% |

0.011*** |

2.23 |

[1.31-3.80] |

Table 5 - Other factors that potentially led to the complications in the

post-bariatric surgery patients who underwent

abdominoplasty.

Figure 2 - Abdominal flap of >2,000 g removed during

abdominoplasty.

Figure 2 - Abdominal flap of >2,000 g removed during

abdominoplasty.

The incidence of diabetes and systemic arterial hypertension in isolation was

not significantly higher in the patients who presented complications after

abdominoplasty (p < 0.09). However, the combined

presence of diabetes and arterial hypertension significantly correlated with

a higher number of complications after AP.

DISCUSSION

After substantial weight loss, complaints of tissue flaccidity and cutaneous

changes, especially in the breasts, abdomen, back, arms, thighs, and face, were

common. In addition to the psychosocial impact of generalized excess skin, there

were clinical implications, including intertrigo and functional limitations in

ambulation, urination, and sexual activity19.

Plastic surgery of the body contour helps promote the social and psychological

reintegration of obese patients, who have prolonged suffering. Moreover, the

objective of these corrective surgeries is to optimize the functional results

obtained with bariatric surgery by removing excess skin2,8.

The results of this study indicated that most of the VBG-RYGB patients who

underwent AP were women with a mean age of 41 years, maximum BMI of 45

kg/m2, mean maximum weight of 119 kg, and mean weight loss of 47

kg. These results agree with those of studies conducted in Brazil9,14,19, Italy20, Austria4,17, France18, Switzerland2, and the United States16.

However, other studies reported a higher mean age, especially in the United

States13,21 and Spain22. Furthermore, a maximum BMI of >50 kg/m2 has been

reported, especially in the United States23-25.

A statistically significant association was found among discomfort, excess skin

after bariatric surgery, and female sex, that is, women were more uncomfortable

with excess skin after bariatric surgery than men26.

The mean BMI before AP was 27.4 kg/m2, which is similar to the results

of other studies in populations from Brazil14, Italy20, Austria4,17, France18,

Switzerland2, and the United

States13,16. However, the mean BMI values reported

in the studies performed in the United States6,24,25, Turkey27, and Greece28 were <27.4 kg/m2.

Residual obesity is a persistent problem in these patients after massive weight

loss. Coon et al.23 reported that 45% and

20% of patients who sought abdominoplasty after VBG-RYGB had BMI values of

>30 and >35 kg/m2, respectively. Orpheu et al.19 reported that the percentage of residual

obesity (BMI > 30 kg/m2) was 27.55%, which agrees with the results

of our study.

A significant reduction in comorbidities was observed after VBG-RYGB, and at the

time of AP, only 11.5% of the patients had systemic arterial hypertension and

5.7% had diabetes mellitus. In the United States, the incidence rates of

arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and sleep apnea syndrome in VBG-RYGB

patients before AP were 32.5%, 15%, and 5%, respectively6.

This significant improvement in comorbidity rates is a direct result of the

decreased number of medications used by the patients after bariatric surgery.

Our results also indicated a significant difference between the mean number of

medications before and after VBG-RYGB (p < 0.001; 95% CI,

3.64-4.69).

Similarly, Lopes et al.12 found that the

mean number of medications per patient decreased from 3.9 ± 1.67 before surgery

to 1.64 ± 1.68 after surgery, corresponding to two drugs per patient (95% CI,

2.38-1.69, p = 0.71), indicating a reduction of >50% in the number of

medications used after surgery12.

The mean duration between bariatric surgery and AP was 43 months. This period is

similar to that reported in one Brazilian study (47 months)14 but higher than that (32 months) reported in another

Brazilian study29 and much higher (22 to

26 months) than that reported in studies on other countries, including

Spain22 and the United States6,25.

The overall complication rate after AP in the VBG-RYGB patients was 31%. This

result is similar to those in the study of de Kerviler et al.2 and Espinosa-de-los-Monteros et al.25 but lower than those in other studies,

wherein the rates ranged from 35% to 50% of the operated patients13,22-24,29.

The observed low rate of major complications, including thromboembolic events,

flap necropsy, and low number of reoperations, may be due to the small number of

combined surgeries observed in this study. Studies that reported higher

complication rates usually involved a higher percentage of combined

surgeries13,23. Combined surgeries lead to longer

surgical time (>6 hours), greater blood loss, and a greater need for blood

transfusions, and these factors may increase the rate of postoperative

complications6,23,29.

The rates of dehiscence, seroma, infection, and necrosis correlated with the

number of surgical procedures23. The

comparison of the patients subjected to one surgical procedure and those

subjected to multiple procedures after bariatric surgery revealed a significant

increase in the rate of postoperative complications in the latter group23.

The execution of combined surgeries is usually discouraged to avoid a longer

surgical time and higher skin damage and deterioration. However, in selected

cases, after careful analysis of clinical, nutritional, emotional, and social

factors, more than one plastic surgery, as was the case in 16 patients (14.8%)

in this study, or other surgical procedures (e.g., herniorrhaphy) may be

performed without the occurrence of serious complications. The combination of

plastic surgery procedures is common in other treatment centers for gastric

bypass patients; however, this strategy should be used only in selected

cases6,13,30.

Another important factor that may have contributed to the lower complication rate

was the low prevalence of comorbidities during AP. A study in the United States

involving 449 gastric bypass patients found a complication rate of 41.8%;

however, the prevalence rates of systemic arterial hypertension and diabetes

mellitus in bariatric surgery patients who underwent plastic surgery were 44.2%

and 22.3%, respectively13.

That same study reported that >50% of patients who sought plastic surgery had

residual obesity. In our study, only 22.3% of the operated patients had grade I

obesity at the time of corrective surgery.

The presence of obesity at the time of AP may have strongly affected the

complication rate related to wound dehiscence16-18.

Some studies reported that the rate of smoking in AP patients was up to 48%.

Smoking is known to increase the risk of wound complications by threefold20,31. The non-inclusion of smokers in the present study may

have contributed to the lower complication rates.

In the present study, the primary clinical and anthropometric factors that were

strongly associated with the postoperative complications in the VBG-RYGB

patients were pre-VBG-RYGB maximum weight, pre-VBG-RYGB BMI, total weight loss,

ΔBMI, and presence of comorbidities. In our study, comorbidities were predictors

of complications. Nonetheless, some studies indicated that comorbidities were

poor predictors of complications13,18.

ΔBMI, especially ΔBMI of >20 kg/m2 (difference in BMI before and

after bariatric surgery), was significantly associated with post-AP

complications in gastric bypass patients, and these results were confirmed by

other studies13,32. Furthermore, the mean weight loss was

higher in the patients with complications, which agrees with the results of

another study16.

Maximum BMI of >50 kg/m2 increases the risk of infections by

2.6-fold higher than does the maximum BMI of <50

kg/m2,13.

The total weight of the resected abdominal tissue during AP significantly

affected the occurrence of postoperative complications, including seroma and

wound dehiscence, especially when the abdominal flap weigh was >2,000 g.

Similarly, other studies reported that the rate of postoperative complications

was increased as the weight of resected tissues was increased in plastic

surgeries performed after bariatric surgery2,17,25,31.

The advent of bariatric surgery has brought lasting and satisfactory results in

the fight against obesity. The patient’s desire after massive weight loss is to

undergo corrective procedures to improve body contouring. The careful and

differentiated approach of the surgeon in each case, together with a

multidisciplinary follow-up, is essential for adequately managing these patients

to improve aesthetic results and prevent complications8,19.

The plastic surgeon should consider the anthropometric, clinical, and surgical

factors that significantly increase the risk of postoperative complications in

bariatric surgery patients. Despite significant weight loss after gastric bypass

surgery, weight loss cannot completely reverse the increased risk of

complications. This fact needs to be evaluated in future studies to identify

strategies to reduce the complication rate in these patients and evaluate

clinical protocols to better prepare these patients for new surgical

procedures.

CONCLUSION

The profile of bariatric surgery patients who underwent AP was represented by

women with a mean age of 41 years, maximum BMI of 46 kg/m2, mean

maximum weight of 120 kg, and mean weight loss of 48 kg. The mean BMI of these

patients before VBG-RYGB was 27.6 kg/m2, and their %EWL was 78.8%. A

significant reduction in comorbidities was observed after VBG-RYGB, including

the complete remission of diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, sleep apnea syndrome,

and metabolic syndrome.

The mean time between VBG-RYGB and AP was 43 months. The overall complication

rate in the VBG-RYGB patients after AP was 31.5%, and the factors significantly

associated with complications were age of >40 years, presence of

comorbidities, removed abdominal flap weight of >2,000 g, and ΔBMI of >20

kg/m2.

COLLABORATIONS

|

SCR

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the

manuscript; conception and design of the study.

|

|

JLSM

|

Final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study;

completion of surgeries and/or experiments.

|

|

LAC

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the

manuscript.

|

|

FGF

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the

manuscript.

|

|

JLDF

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the

manuscript.

|

|

LRC

|

Statistical analyses; writing the manuscript or critical review of

its contents.

|

REFERENCES

1. Karlsson J, Taft C, Rydén A, Sjöström L, Sullivan M. Ten-year trends

in health-related quality of life after surgical and conventional treatment for

severe obesity. the SOS intervention study. Int J Obes (Lond).

2007;31(8):1248-61. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0803573

2. de Kerviler S, Hüsler R, Banic A, Constantinescu MA. Body contouring

surgery following bariatric surgery and dietetically induced massive weight

reduction: a risk analysis. Obes Surg. 2009;19(5):553-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11695-008-9659-8

3. Sjöström L, Peltonen M, Jacobson P, Sjöström CD, Karason K, Wedel H,

et al. Bariatric surgery and long-term cardiovascular event. JAMA.

2012;307(1):56-65. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1914

4. Felberbauer FX, Shakeri-Leidenmühler S, Langer FB, Kitzinger H,

Bohdjalian A, Kefurt R, et al. Post-Bariatric Body-Contouring Surgery: Fewer

Procedures, Less Demand, and Lower Costs. Obes Surg. 2015;25(7):1198-202. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1493-6

5. Poirier P, Cornier MA, Mazzone T, Stiles S, Cummings S, Klein S, et

al.; American Heart Association Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition,

Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Bariatric surgery and cardiovascular risk

factors: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association.

Circulation. 2011;123(15):1683-701. PMID: 21403092 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182149099

6. Shermak MA, Chang D, Magnuson TH, Schweitzer MA. An outcomes

analysis of patients undergoing body contouring surgery after massive weight

loss. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(4):1026-31. PMID: 16980866 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000232417.05081.db

7. Michaels J 5th, Coon D, Rubin JP. Complications in postbariatric

body contouring: strategies for assessment and prevention. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2011;127(3):1352-7. PMID: 21364438 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182063144

8. van der Beek ES, Geenen R, de Heer FA, van der Molen AB, van

Ramshorst B. Quality of life long-term after body contouring surgery following

bariatric surgery: sustained improvement after 7 years. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2012;130(5):1133-9. PMID: 22777040 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e318267d51d

9. Silva CF, Cohen L, Sarmento LA, Rosa FMM, Rosado EL, Carneiro JRI,

et al. Efeitos no longo prazo da gastroplastia redutora em Y-de-Roux sobre o

peso corporal e comorbidades clínico metabólicas em serviço de cirurgia

bariátrica de um hospital universitário. ABCD Arq Bras Cir Dig.

2016;29(Supl.1):20-3.

10. Projeto Diretrizes. Associação Médica Brasileira e Conselho Federal

de Medicina. Sobrepeso e Obesidade: Diagnóstico. Brasília: Sociedade Brasileira

de Endocrinologia e Metabologia; 2004.

11. Duarte RLM, Magalhães-da-Silveira FJ. Fatores preditivos para apneia

obstrutiva do sono em pacientes em avaliação pré-operatória de cirurgia

bariátrica e encaminhados para polissonografia em um laboratório do sono. J Bras

Pneumol. 2015;41(5):440-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1806-37132015000000027

12. Lopes EC, Heineck I, Athaydes G, Minhardt NG, Souto KEP, Stein AT.

Is Bariatric Surgery Effective in Reducing Comorbidities and Drug Costs? A

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Obes Surg. 2015;25(9):1741-9. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11695-015-1777-5

13. Coon D, Gusenoff JA, Kannan N, El Khoudary SR, Naghshineh N, Rubin

JP. Body mass and surgical complications in the post-bariatric reconstructive

patient: analysis of 511 cases. Ann Surg. 2009;249(3):397-401. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e318196d0c6

14. Donnabella A, Neffa L, Barros BB, Santos FP. Abdominoplastia pós

cirurgia bariátrica: experiência de 315 casos. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2016;31(4):510-5.

15. Cintra Junior W, Modolin MLA, Rocha RI, Gemperli R. Mastopexia de

aumento após cirurgia bariátrica: avaliação da satisfação das pacientes e

resultados cirúrgicos. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2016;43(3):160-4.

16. Arthurs ZM, Cuadrado D, Sohn V, Wolcott K, Lesperance K, Carter P,

et al. Post-bariatric panniculectomy: pre-panniculectomy body mass index impacts

the complication profile. Am J Surg. 2007;193(5):567-70. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.01.006

17. Parvizi D, Friedl H, Wurzer P, Kamolz L, Lebo P, Tuca A, et al. A

Multiple Regression Analysis of Postoperative Complications After

Body-Contouring Surgery: a Retrospective Analysis of 205 Patients: Regression

Analysis of Complications. Obes Surg. 2015;25(8):1482-90. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11695-014-1559-5

18. Bertheuil N, Thienot S, Huguier V, Ménard C, Waltier E. Medial

thighplasty after massive weight loss: are there any risk factors for

postoperative complications? Aesth Plast Surg. 2014;38(1):63-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00266-013-0245-7

19. Orpheu SC, Coltro PS, Scopel GA, Saito FL, Ferreira MC. Cirurgia do

contorno corporal no paciente após perda ponderal maciça: experiência de três

anos em hospital público secundário. Rev Assoc Med Bras. 2009;55(4):427-33. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S0104-42302009000400018

20. Fraccalvieri M, Datta G, Bogetti P, Verna G, Pedrale R, Bocchiotti

MA, et al. Abdominoplasty after weight loss in morbidly obese patients: a 4-year

clinical experience. Obes Surg. 2007;17(10):1319-24. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11695-007-9235-7

21. Sanger C, David LR. Impact of significant weight loss on outcome of

body-contouring surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56(1):9-13. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.sap.0000186512.98072.07

22. Vilà J, Balibrea JM, Oller B, Alastrué A. Post-bariatric surgery

body contouring treatment in the public health system: cost study and perception

by patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134(4):448-54.

23. Coon D, Michaels J 5th, Gusenoff JA, Purnell C, Friedman T, Rubin

JP. Multiple procedures and staging in the massive weight loss population. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(2):691-8. PMID: 20124854 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c87b3c

24. Taylor J, Shermak M. Body contouring following massive weight loss.

Obes Surg. 2004;14(8):1080-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1381/0960892041975578

25. Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, de la Torre JI, Rosenberg LZ, Ahumada

LA, Stoff A, Williams EH, et al. Abdominoplasty with total abdominal liposuction

for patients with massive weight loss. Aesth Plast Surg. 2006;30(1):42-6. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00266-005-0126-9

26. Giordano S, Victorzon M, Koskivuo I, Suominen E. Physical discomfort

due to redundant skin in post-bariatric surgery patients. J Plast Reconstr

Aesthet Surg. 2013;66(7):950-5. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2013.03.016

27. Menderes A, Baytekin C, Haciyanli M, Yilmaz M. Dermalipectomy for

body contouring after bariatric surgery in Aegean region of Turkey. Obes Surg.

2003;13(4):637-41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1381/096089203322190880

28. Fotopoulos L, Kehagias I, Kalfarentzos F. Dermolipectomy following

weight loss after surgery for morbid obesity. Obes Surg. 2000;10(5):451-9. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1381/096089200321593959

29. Canan Junior LW. Abdominoplastia após grandes perdas ponderais:

análise crítica de complicações em 130 casos consecutivos. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2013;28(3):381-8.

30. Gmür RU, Banic A, Erni D. Is it safe to combine abdominoplasty with

other dermolipectpmy procedures to correct skin excess after weight loss? Ann

Plast Surg. 2003;51(4):353-7. PMID: 14520060

31. Manassa EH, Hertl CH, Olbrisch RR. Wound healing problems in smokers

and nonsmokers after 132 abdominoplasties. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2003;111(6):2082-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000057144.62727.C8

32. Nemerofisky RB, Oliak DA, Capella JF. Body lift: an account of 200

consecutive cases in the massive weight loss patient. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2006;117(2):414-30. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000197524.18233.bb

1. Hospital Regional da Asa Norte, Brasília, DF,

Brazil.

2. Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, DF,

Brazil.

3. Escola Superior de Ciências da Saúde, Curso de

Medicina, Brasília, DF, Brazil.

4. Secretaria de Estado de Saúde, Brasília, DF,

Brazil.

5. Hospital Universitário de Brasília, Brasília,

DF, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Jefferson Lessa Soares

de Macedo, SQS 213, Bloco H, Apto 303 - Asa Sul, Brasília, DF,

Brazil. Zip Code 70292-080. E-mail:

jlsmacedo@yahoo.com.br

Article received: January 18, 2018.

Article accepted: May 17, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.