INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is currently one of the most common health problems in the world.

In Brazil, its incidence has been increasing gradually. Excluding skin cancer,

breast cancer is the most frequent type of cancer that affects women

worldwide1.

Total mastectomy, especially in some developing countries and centers further

away, is still widely employed for the treatment of breast cancer. This surgery

and other adjuvant therapies may contribute to the development of physical and

psychological complications, which can negatively influence patients’ quality of

life2-4. After mastectomy, the loss of breast alters the body

image of women and yields a feeling of mutilation and loss of femininity and

sensuality5,6.

In an attempt to reduce the negative feelings related to the disease and its

treatment, improve self-esteem, and address the loss of breast, many women opt

for surgical reconstruction7. This is a

safe procedure, which does not increase the risk of recurrence, interfere with

detection of the disease, or lead to delay in adjuvant therapies. There are

several surgical procedures such as conservative techniques, adjacent flaps,

alloplastic materials, and myocutaneous pedicle flaps microcirúrgicos8-12.

Law 12, 802/2013 requires the Unified Health System (SUS) to provide

reconstructive plastic surgery of the breast soon after mastectomy when clinical

conditions permit. However, there is often no structure in public hospitals to

perform such procedures. Further, there are deficiencies ranging from lack of

operating rooms to the absence of qualified medical personnel and suitable

material. Thus, reconstruction is for the second half. However, owing to the

high demand of the SUS, many of these patients are waiting for reconstruction in

rows, which often seem intermináveis12.

The Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (SBCP) estimates that the average

waiting time for reconstruction is 10 years; in 2015, only 1100 breast

reconstructions were performed by the SUS12.

Many civil institutions, such as the SBCP, in partnership with the NHS, often

offer solutions to mitigate these situations. Among these solutions, we can

mention Mutirões12.

From October 24 to 29, 2016, the SBCP promoted the 2nd National Task

Force of Breast Reconstruction (NTFBR), which included the participation of more

than 800 professionals in the specialized area. Approximately 840 women who

underwent mastectomy were operated on for free by plastic surgeons, aiming at

the possibility of rebuilding mamária12.

The Plastic Surgery Service of Walter Cantídio University Hospital (SCPMR-HUWC)

also collaborated on this project in 2016, with heterogeneous participation of

plastic surgeons and completion of 16 breast reconstructions.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to analyze the results of the 2nd

NTFBR, held in October 2016 in SCPMR-HUWC, with a heterogeneous group of plastic

surgeons.

METHODS

A prospective cohort study was conducted, in which 16 patients who underwent

breast reconstruction in SCPMR-HUWC and were included in the second NTFBR held

in October 2016, were evaluated.

The study was approved by the Ethics in Research CAAE: 69439917.0.0000.5045 and

was conducted in accordance with Resolution 466/12 of the National Health

Council, which approved the regulatory guidelines and standards for research

involving humans.

The Task Force in question included all patients who were in the queue for breast

reconstruction surgery in SCPMR-HUWC. We collected the following data: age,

waiting time in the queue, type of breast reconstruction performed, length of

hospital stay, and postoperative complications.

The patients were followed up for 6 months; their data were tabulated and

analyzed by the investigators using the statistical software

Epi-Info®, and were considered significant at p

< 0.05 with a confidence interval of 95%.

RESULTS

A total of 16 female patients were subjected to post-mastectomy breast

reconstruction and cardiovascular and surgical risk evaluations; all patients

were found to be fit for reconstruction.

No patient was under treatment with chemotherapy (QMT) or radiotherapy (RTX). All

patients were to undergo delayed reconstruction (more than 1 year after

mastectomy and free from any adjuvant procedure like QMT and RTX for more than a

year).

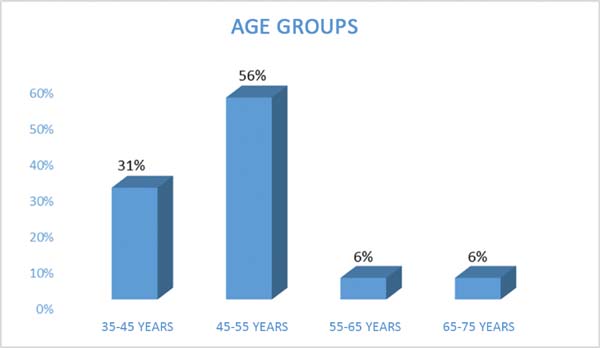

The patients’ ages ranged from 39 to 72 years, mean 49 years for the

reconstruction (Figure 1).

Figura 1 - Age of patients undergoing post-mastectomy breast

reconstruction.

Figura 1 - Age of patients undergoing post-mastectomy breast

reconstruction.

None of the patients presented with skin disorders, radiodermatitis, pyoderma,

tumors, or significant deformities in the surgical site.

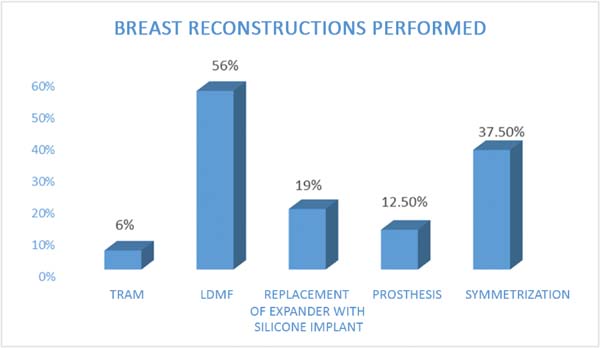

The following types of reconstruction were performed: one (6%) rectus muscle

myocutaneous flap (TRAM) creation, nine (56%) latissimus dorsi muscle

myocutaneous flap (RGD) creations, five prosthesis [three (19%) with exchange

with unilateral prosthesis expanders and two (12.5%) with unilateral prosthesis

(right)] implantations, and six (37.5%) symmetrizations (Figures 2 to 6).

The length of hospital stay ranged from 1 to 5 days; approximately 82% of the

patients passed 4 days or less.

Figure 2 - Number of breast reconstructions performed in the National

Program for Breast Reconstruction according to the technique LDMF,

latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap; RAMF, rectus abdominis

myocutaneous flap.

Figure 2 - Number of breast reconstructions performed in the National

Program for Breast Reconstruction according to the technique LDMF,

latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap; RAMF, rectus abdominis

myocutaneous flap.

Figura 3 - Breast reconstruction using the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous

flap after mastectomy.

Figura 3 - Breast reconstruction using the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous

flap after mastectomy.

Figure 4 - Breast reconstruction, replacement of expander with silicone

implant and post-mastectomy symmetrization.

Figure 4 - Breast reconstruction, replacement of expander with silicone

implant and post-mastectomy symmetrization.

Figura 5 - Breast reconstruction using the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous

flap after mastectomy.

Figura 5 - Breast reconstruction using the latissimus dorsi myocutaneous

flap after mastectomy.

Figura 6 - Breast reconstruction using the rectus abdominis myocutaneous

flap after mastectomy.

Figura 6 - Breast reconstruction using the rectus abdominis myocutaneous

flap after mastectomy.

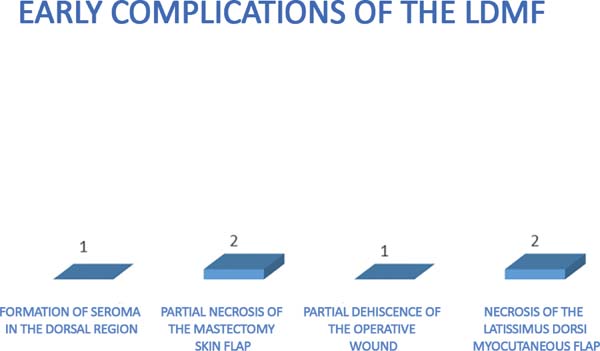

The complications were divided into early (those that occurred within 30 days

after surgery) and late (those that occurred after 30 days). The earliest

complications observed were seroma in the dorsal region (13%), partial necrosis

of the mastectomy skin (6%), dehiscence of the operative wound (13%), and

necrosis of the latissimus dorsi flap (6%) (Figures 7 and 8).

Figura 7 - Early complications of breast reconstruction using the latissimus

dorsi myocutaneous flap after mastectomy.

Figura 7 - Early complications of breast reconstruction using the latissimus

dorsi myocutaneous flap after mastectomy.

Figura 8 - Early complications of breast reconstruction using the latissimus

dorsi myocutaneous flap after mastectomy.

Figura 8 - Early complications of breast reconstruction using the latissimus

dorsi myocutaneous flap after mastectomy.

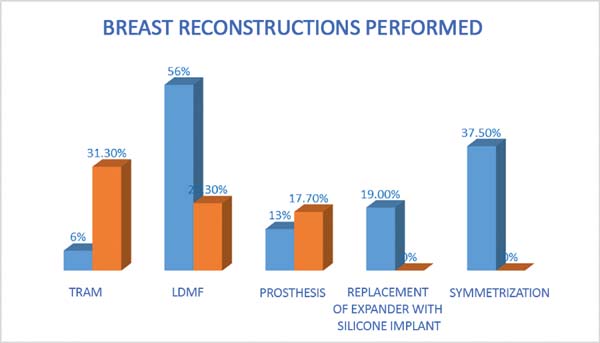

Figure 9 - Number of breast reconstructions performed according to technique

Plastic Surgery Service of the Walter Cantídio University Hospital

(in blue); statistical analysis of the study by Cosac et al.

16 (in red). LDMF, latissimus

dorsi myocutaneous flap; TRAM, rectus abdominis myocutaneous

flap.

Figure 9 - Number of breast reconstructions performed according to technique

Plastic Surgery Service of the Walter Cantídio University Hospital

(in blue); statistical analysis of the study by Cosac et al.

16 (in red). LDMF, latissimus

dorsi myocutaneous flap; TRAM, rectus abdominis myocutaneous

flap.

None of the risk factors (i.e., hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, BMI,

and age) was significantly associated with the early complications. All early

complications occurred only in the patients with RGDs.

None of the 16 patients had any late complications such as implant coverage

changes, capsular contraction, or muscle and skin atrophies.

DISCUSSION

Breast reconstruction is gaining an increasingly important role in the treatment

of breast cancer because of the proven psychological and physical benefits for

patients. This procedure favors faster return of these patients to social life,

improves immunity, and thus offers better prognosis in the treatment of the

disease13,14.

Many reconstruction techniques have been developed over the years. The most

commonly used procedures are as follows:

Creation of myocutaneous pedicle flaps, such as latissimus dorsi muscle

flaps;

Creation of retail transverse rectus abdominis muscle flaps;

Implantation of alloplastic materials, such as temporary or permanent

tissue expanders;

Implantation of silicone.

In this scenario, there is evidence of indications of breast reconstruction with

the use of local flaps, and the alloplastic materials RGD over the TRAM, which

has a higher morbidity and systemic site15.

In the study by Cosac et al.16, the most

used technique was TRAM reconstruction (31.3%), followed by RGD (30%), and

prosthesis (17.7%). However, reconstruction using exchange expander prosthesis

and symmetrization were not studied. In our study, the type of reconstruction

performed constituted TRAM (6%), RGD (56%), 13% and symmetrization prosthesis

(37.5%) (Figure 9).

For the treatment for breast cancer, adjuvant radiation therapy is often

performed after mastectomy in women diagnosed with breast cancer stages II and

III. This increases local control, disease-free survival, and survival

globally17-20.

Despite the improvement of the oncological results, adjuvant radiation therapy in

women with breast cancer may worsen the aesthetic results due to tissue

atrophies and capsular contractures and increase the risk of loss of rebuilding

mamária21.

Seroma in the donor area of the latissimus dorsi muscle is the most common

complication of the procedure, with a reported rate of 16% to 79%22-25.

However, the significance of seroma as a major complication requiring further

surgery is low. In the present study, we observed a rate of 13% seroma. Gart et

al.15 reported that 1079 patients

from the database of American College of Surgeons National Surgical Improvement

Program (ACS-NSQIP) undergoing RGD, showed early complications like reoperations

(5.7%), cutaneous infections (3.3%), necrosis (1.3%), surgical wound dehiscence

(0.6% ), and other complications (3.2%) 26.

Early complications were observed in this joint Task Force of the case 1 (6%)

partial mastectomy skin necrosis and 2 cases (13%) partial dehiscence of the

surgical wound. These complications occurred probably due to the ineffective

surgical procedure resulting in patchwork, thin mastectomy, and hypoperfused

skin. There was 1 case of necrosis of the flap of latissimus dorsi, but no cases

of infection or other clinical complications.

In a case series of 100 cases, Perdikis et al.22 observed a capsular contracture rate of in patients undergoing

RGD and 6% in those with silicone implants. In another series of 53 cases, Venus

& Prinsloo26 observed 7.4% of

capsular contracture in cases that required capsulotomy and 33% of capsular

contracture in those that did not require surgery.

In the present study of 16 patients, none showed any changes in implant coverage

like muscle and skin atrophy.

We note that five days were enough to clear the queue of the 16 SCPMR-HUWC

patients waiting for breast reconstruction.

The vast majority of patients were discharged in less than four days, which shows

that this kind of a joint Task Force does not hinder the operation of the

hospital hotel structure.

The surgeries were performed on 2 consecutive weekends, and the surgical

operation was also unaffected, because the SCPMR-HUWC elective surgeries are

mostly performed during the week.

Because the task forces comprised of a heterogeneous group of plastic surgeons

from other institutions, it encouraged an exchange of experiences and

innovations in techniques, as well as established new partnerships and

strengthened old ties.

Plastic surgery has an important role in the treatment of patients with breast

cancer. In this work, a high degree of satisfaction in patients was observed due

to the results and few complications. However, in spite of the surgeries being

elective and performed by senior plastic surgeons, we had a high number of

complications. This rate was consistent with that in the literature, probably in

the study in question, of a fortuitous nature. Thus, we conclude that the joint

Task Forces of breast reconstruction for post mastectomy cases are a viable

alternative in terms of public health.

COLLABORATIONS

|

AM

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses;

conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or

experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its

contents.

|

|

SGPP

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the

manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of

surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical

review of its contents.

|

REFERENCES

1. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer. José

Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2012: Incidência de Câncer no Brasil.

Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2011.

2. Cheville AL, Tchou J. Barriers to rehabilitation following surgery

for primary breast cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2007;95(5):409-18. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jso.20782

3. Ribeiro RVE, Silva GB, Augusto FV. Prevalência do transtorno

dismórfico corporal em pacientes candidatos e/ou submetidos a procedimentos

estéticos na especialidade da cirurgia plástica: uma revisão sistemática com

meta-análise. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2017;32(3):428-35.

4. Ching AW, Costa MP, Brasolin AG, Ferreira LM. Influência das

complicações pós-operatórias no insucesso da reconstrução de mama imediata com

implante de silicone. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(2):182-9.

5. Alves VL, Sabino Neto M, Abla LEF, Oliveira CJR, Ferreira LM.

Avaliação precoce da qualidade de vida e autoestima de pacientes mastectomizadas

submetidas ou não à reconstrução mamária. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2017;32(2):208-17.

6. Sheppard LA, Ely S. Breast cancer and sexuality. Breast J.

2008;14(2):176-81. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4741.2007.00550.x

7. Keith DJ, Walker MB, Walker LG, Heys SD, Sarkar TK, Hutcheon AW, et

al. Women who wish breast reconstruction: characteristics, fears, and hopes.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(3):1051-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000046247.56810.40

8. Cammarota MC, Galdino MCA, Lima RQ, Almeida CM, Ribeiro Junior I,

Moura LG, et al. Avaliação das simetrizações imediatas em reconstrução de mama.

Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2017;32(1):56-63.

9. Oliveira LD. Análise retrospectiva da casuística pessoal em

mamoplastia redutora utilizando a técnica de pedículo inferior em suas

diferentes indicações. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2016;31(3):321-7.

10. Miranda RE, Pereira JB, Gragnani Filho A. Uso de duas telas de

polipropileno na área doadora do TRAM para reconstrução mamária: avaliação na

incidência de hérnia e abaulamento abdominal. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2015;30(4):560-6.

11. Tavares-Filho JM, Franco D, Moreto L, Porchat C, Franco T.

Utilização do retalho miocutâneo de grande dorsal, com extensão adiposa, nas

reconstruções mamárias: uma opção para preenchimento do polo superior. Rev Bras

Cir Plást. 2015;30(3):423-8.

12. Saldanha Filho OR, Saldanha O, Cação E, Menegazzo MR, Cazeto D,

Canchica AC, et al. Reconstrução de mama com miniabdominoplastia reversa. Rev

Bras Cir Plást. 2017;32(4):505-12.

13. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP). Câncer de mama:

mutirão de reconstrução mamária vai realizar 842 cirurgias. São Paulo; 2016.

[acesso 2017 Abr 16]. Disponível em: http://www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br/2016/10/20/cancer-de-mama-mutirao-de-reconstrucao-mamaria-vai-realizar-842-cirurgias/

14. Veiga DF, Veiga-Filho J, Ribeiro LM, Archangelo I Jr, Balbino PF,

Caetano LV, et al. Quality-of-life and self-esteem outcomes after oncoplastic

breast-conserving surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(3):811-7. PMID:

20195109 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181ccdac5

15. Bellino S, Fenocchio M, Zizza M, Rocca G, Bogetti P, Bogetto F.

Quality of life of patients who undergo breast reconstruction after mastectomy:

effects of personality characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(1):10-7

PMID: 21200194 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181f956c0

16. Gart MS, Smetona JT, Hanwright PJ, Fine NA, Bethke KP, Khan SA, et

al. Autologous options for postmastectomy breast reconstruction: a comparison of

outcomes based on the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality

Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216(2):229-38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2012.11.003

17. Cosac OM, Camara Filho JPP, Barros APGSH, Borgatto MS, Esteves BP,

Curado DMDC, et al. Reconstruções mamárias: estudo retrospectivo de 10 anos. Rev

Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(1):59-64. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752013000100011

18. Overgaard M, Hansen PS, Overgaard J, Rose C, Andersson M, Bach F, et

al. Postoperative radiotherapy in high-risk premenopausal women with breast

cancer who receive adjuvant chemotherapy. Danish Breast Cancer Cooperative Group

82b Trial. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(14):949-55. DOI: 10.1056/NEJM199710023371401

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199710023371401

19. Saliba GAM, Carvalho EES, Silva Filho AF, Alves JCRR, Tavares MV,

Costa SM, et al. Reconstrução mamária: análise de novas tendências e suas

complicações maiores. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013;28(4):619-26.

20. Ragaz J, Jackson SM, Le N, Plenderleith IH, Spinelli JJ, Basco VE,

et al. Adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy in node-positive premenopausal

women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(14):956-62. DOI:

10.1056/NEJM199710023371402 DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199710023371402

21. Clarke M, Collins R, Darby S, Davies C, Elphinstone P, Evans E, et

al.; Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of

radiotherapy and of differences in the extent of surgery for early breast cancer

on local recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials.

Lancet. 2005;366(9503):2087-106. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67887-7

22. Shah C, Kundu N, Arthur D, Vicini F. Radiation therapy following

postmastectomy reconstruction: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol.

2013;20(4):1313-22. DOI: 10.1245/s10434-012-2689-4 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2689-4

23. Perdikis G, Koonce S, Collis G, Eck D. Latissimus dorsi myocutaneous

flap for breast reconstruction: bad rap or good flap? Eplasty. 2011;11:e39.

PMID: 22031843

24. Farah AB, Nahas FX, Mendes JA. Reconstrução mamária em dois estágios

com expansores de tecido e implantes de silicone. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2015;30(2):172-81.

25. Delay E, Gounot N, Bouillot A, Zlatoff P, Rivoire M. Autologous

latissimus breast reconstruction: a 3-year clinical experience with 100

patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(5):1461-78. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199810000-00020 DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199810000-00020

26. Bonomi S, Settembrini F, Salval A, Gregorelli C, Musumarra G,

Rapisarda V. Current indications for and comparative analysis of three different

types of latissimus dorsi flaps. Aesthet Surg J. 2012;32(3):294-302. DOI:

10.1177/1090820X12437783 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1090820X12437783

27. Venus MR, Prinsloo DJ. Immediate breast reconstruction with

latissimus dorsi flap and implant: audit of outcomes and patient satisfaction

survey. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(1):101-5. DOI:

10.1016/j.bjps.2008.08.064 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2008.08.064

1. University of Belgrade, Belgrade,

Serbia.

2. Hospital Universitário Walter Cantídio,

Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Aleksandra

Markovic, Av. Beira Mar, 4260 - Praia de Mucuripe - Fortaleza, CE,

Brazil. Zip Code 60165-121. E-mail:

19quepasa19@gmail.com

Article received: September 27, 2017.

Article accepted: June 22, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.