INTRODUCTION

Following the introduction of radical mastectomy by Halsted1, breast cancer surgery underwent a substantial evolution

during the 20th century as a result of the incorporation of new

techniques, new technologies, and the biomolecular analysis of tumors. Until the

1970s, the gold standard surgical treatment was radical mastectomy, which was

considered a great success at the time.

However, the fear of mutilation and loss of quality of life felt by many women

has motivated the search for less aggressive techniques for the locoregional

control of the disease. Thus, interventions such as modified radical mastectomy,

simple mastectomy, and conservative breast surgery have been included in the

oncological surgery repertoire, with comparable results in terms of disease-free

survival2 while offering the patients

an improved perception of quality of life and body image3.

Advances in breast reconstruction surgery have occurred parallel to the evolution

of ablative treatment of mastectomy patients. Surgery with autologous flaps

advanced greatly with the use of microsurgery and the description of

angiosomes4 and perforator-based

flaps, which became excellent options for reconstruction, causing little or no

damage to the donor area. The advent and implementation of novel materials

developed in recent years, such as anatomical implants, expanders, and acellular

dermal matrices, has also contributed to the success of breast reconstruction

procedures.

Although breast reconstruction has obvious and significant benefits for the

quality of life of mastectomy patients5,

more than 60% of these women do not undergo the procedure6. The decision to have breast reconstruction involves a

number of variables and may be associated with sociodemographic and ethnic

factors or even medical conditions. Since 2013, a law in Brazil states that any

woman undergoing mastectomy within the Unified Health System (SUS) should be

guaranteed immediate reconstruction, in the context of favorable medical

circumstances7.

Mastectomy with immediate breast reconstruction may prevent patients from

experiencing a period of psychosocial stress, negative body image, and sexual

dissatisfaction, as compared to late reconstruction8. Immediate breast reconstruction is typically performed

using implants or expanders, especially in light of the increasing popularity of

skin-sparing mastectomy, nipple-areola-complex (NAC)-sparing mastectomy, and

even prophylactic mastectomy. It is estimated that reconstruction with implants

will increase by an average of 5% per year9, owing to the acceptable rate of complications and proven

oncological safety of this technique10.

The use of acellular dermal matrices has also contributed to the increased number

of immediate implant-based reconstructions, as it provides better implant

coverage, expansion of the submuscular pocket11, and reduced rates of capsular contracture12. However, most published studies have reported on the

use of matrices of human origin. Since Brazilian laws do not permit the use of

this type of product and the cost of dermal matrices of animal origin is still

high in Brazil, new materials have been implemented with the aim of obtaining

the obvious cosmetic benefits of these matrices.

The surgical use of synthetic meshes has been widely studied, and they have been

shown to be safe, biocompatible, and hypoallergenic, with a low rate of

complications13. Therefore, these

materials may be effective replacements for dermal matrices in implant-based

breast reconstruction surgery.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to report the author’s experience using a technique of

implant-based breast reconstruction with synthetic mesh as an alternative to

acellular dermal matrices.

METHOD

Patient selection

This was a retrospective analysis of 12 consecutive patients (20

reconstructed breasts) who underwent immediate or delayed breast

reconstruction using the described technique with implants and synthetic

mesh between November 2015 and December 2016.

All patients were operated by the author at the private clinic and at the

breast center of the Integrated Oncology Center (Centro de Oncologia

Integrado - COI) in Rio de Janeiro, RJ.

Decisions regarding patient selection, mastectomy technique indication,

incision location, and possibility of immediate breast reconstruction with

implants were made in consultation with the mastology team.

All patients underwent preoperative evaluation with detailed anamnesis,

physical examination, laboratory testing, and X-rays. The following

demographic data were obtained: age, history of the current disease, history

of comorbidities, smoking habits, and previous neoadjuvant chemotherapy or

radiotherapy. Preoperative photographic documentation was also included.

Physical examination included breast palpation and the measurement of breast

width, height, and projection. Assessment of the contralateral breast (in

cases of unilateral reconstruction), asymmetries, ptosis, thorax shape, and

patient’s biotype was also performed. Together with the mastectomy

technique, these data were essential in the estimation of the implant

volume. All patients underwent breast reconstruction with textured

anatomical implants Mentor® (Santa Barbara, CA) and

semi-absorbable mesh ULTRAPRO® (Ethicon, a Johnson & Johnson

company, Amersfoort, The Netherlands).

Surgical technique

The location and type of incision are discussed with the mastology team,

taking into account the tumor location, breast shape, ptosis, and patient’s

expectations.

At the end of the mastectomy (skin-sparing, areola-sparing, or prophylactic),

in cases of immediate reconstruction, the skin flap is assessed, as well as

the patient’s oncological status. The flap is assessed clinically (color,

capillary filling, and thickness). If there are signs of vascular injury,

immediate reconstruction with implants is aborted and two-stage

reconstruction with an expander is performed. In cases of the node-positive

axilla, an indication for intraoperative adjuvant radiotherapy is another

essential factor in determining the choice of technique. Due to the high

incidence of capsular contracture in patients with implants who undergo

radiotherapy, tissue expander-based reconstruction is another option.

Reconstruction begins with the detachment of the pectoralis major through its

free margin and from the sternum and inframammary fold, without sectioning

it and maintaining its attachment to the fascia. The size of the subpectoral

pocket is calculated based on the desired volume of the implant and the

patient’s anatomy. A mold with the desired volume of the implant is then

inserted in the partial submuscular pocket to gauge the size of the fascia

of the serratus anterior muscle that will be lifted to accommodate the

lateral portion of the implant, where the mesh will be sutured.

After the dissection of the fascia of the serratus anterior muscle, the

patient is seated on the operating table, the mold is once again inserted,

and the incision is closed temporarily with a skin stapler. At this point,

symmetry, contour, and position of the inframammary fold are assessed and

the ideal implant is selected. The submuscular pocket is then irrigated with

antibiotic solution (cefazolin + garamycin), and a vacuum suction drain and

the implant are inserted.

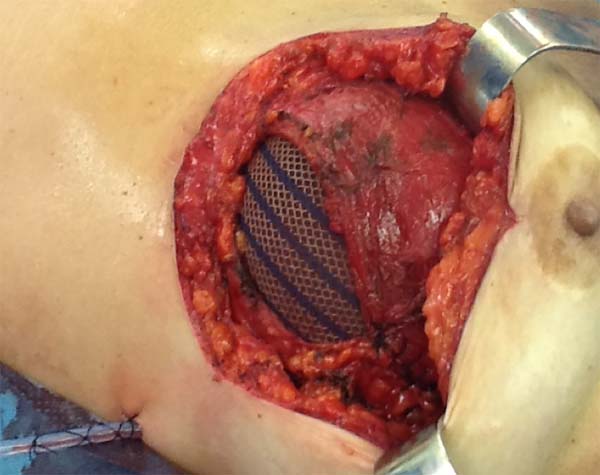

The superior-lateral portion of the pectoralis major is sutured to the fascia

of the serratus anterior muscle with Vicryl 2-0, and the mesh is placed over

the exposed portion of the implant. The mesh is then sutured with PDS thread

2-0 to the lateral margin of the pectoralis major and the fascia of the

serratus anterior muscle to support the implant laterally and inferiorly

(Figure 1). Intramuscular local

anesthesia with bupivacaine solution (20 mL) is administered to reduce

postoperative pain. The skin is then sutured in three layers, and the

incision is covered with Steri-Strip® (Figures 2 and 3)

and a surgical bra.

Figura 1 - Demonstration of the use of a mixed mesh sutured between the

pectoralis major and serratus anterior muscles.

Figura 1 - Demonstration of the use of a mixed mesh sutured between the

pectoralis major and serratus anterior muscles.

Figura 2 - Perioperative lateral view of a patient undergoing

prophylactic bilateral adenomastectomy with implant and mixed

mesh.

Figura 2 - Perioperative lateral view of a patient undergoing

prophylactic bilateral adenomastectomy with implant and mixed

mesh.

Figura 3 - Perioperative lateral view of a patient undergoing

prophylactic bilateral adenomastectomy with implant and mixed

mesh.

Figura 3 - Perioperative lateral view of a patient undergoing

prophylactic bilateral adenomastectomy with implant and mixed

mesh.

In one case of secondary reconstruction, the technique had to be slightly

modified owing to insufficient muscle coverage. In that case, because the

pectoralis major had been sectioned during the primary surgery, the lower

lateral portion of the mesh was sutured to the serratus anterior muscle and

the aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis muscle, while the upper portion was

sutured to the small lobe of the remaining pectoralis major (Figure 4). In addition, capsulotomy or

capsulectomy was performed in these cases.

Figure 4 - Perioperative view of a patient undergoing secondary breast

reconstruction. Owing to insufficient muscle coverage, the

inferior portion of the mesh was sutured in the aponeurosis of

the rectus abdominis muscle, laterally to the fascia of the

serratus anterior muscle and superiorly to the pectoralis

major.

Figure 4 - Perioperative view of a patient undergoing secondary breast

reconstruction. Owing to insufficient muscle coverage, the

inferior portion of the mesh was sutured in the aponeurosis of

the rectus abdominis muscle, laterally to the fascia of the

serratus anterior muscle and superiorly to the pectoralis

major.

Postoperative period

The patients were discharged from the hospital between 24 and 48 hours after

surgery and administered antibiotics. Rest with moderate activity for a

period of 30-45 days was recommended, along with the use of a surgical

bra.

The patients were monitored weekly during the first postoperative month and

then again at three and six months postoperatively. The drains were removed

when drainage was less than 30 mL/day.

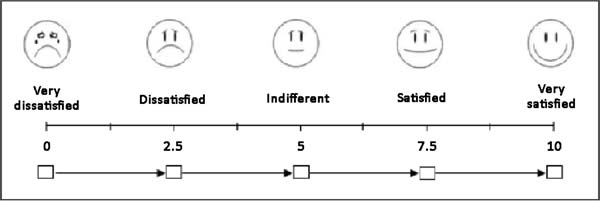

At postoperative 6 months, the patients were photographed and asked to

describe their level of satisfaction regarding the surgical technique that

was used by giving each parameter a score from 0 to 10, based on a visual

analog scale (Figure 5). The following

parameters were assessed: sensitivity, appearance, texture, symmetry, and

scar quality. In addition, the patients were asked whether they would choose

a different technique, with response options of “yes”, “maybe”, and

“no”.

Figure 5 - Visual analog scale used in the analysis of the patient’s

degree of satisfaction.

Figure 5 - Visual analog scale used in the analysis of the patient’s

degree of satisfaction.

Lastly, the potential complications of the technique, including infection

(requiring intravenous antibiotics), necrosis of the mastectomy flap or of

the NAC, seroma, hematoma, suture dehiscence, rippling, and

capsular contracture, were analyzed.

RESULTS

Twelve patients (20 breasts) underwent breast reconstruction with mixed mesh and

implants between November 2015 and December 2016. The mean age of the patients

was 55.6 years (35-67 years), and the mean body mass index (BMI) was 25.6

kg/m2 (19-29 kg/m2). The most common comorbidities

were hypertension (16%) and hypothyroidism (8%). One patient (8%) was a smoker,

two patients (16%) had a previous history of radiotherapy, one patient (8%) had

a history of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and three patients (25%) had undergone

breast surgery. The mean follow-up time was 14 months (Table 1).

Table 1 - Patients’ characteristics.

| Age |

55.6 years (36-67 years) |

| BMI |

25.6 kg/m2 (19-29

kg/m2).

|

| Hypertension |

n = 2 (16%) |

| Hypothyroidism |

n = 1 (8%) |

| Smoking |

n = 1 (8%) |

| Previous radiotherapy |

n = 2 (16%) |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy |

n = 1 (8%) |

| Previous breast surgery |

n = 3 (25%) |

| Follow-up |

14 months (6-18 months) |

Table 1 - Patients’ characteristics.

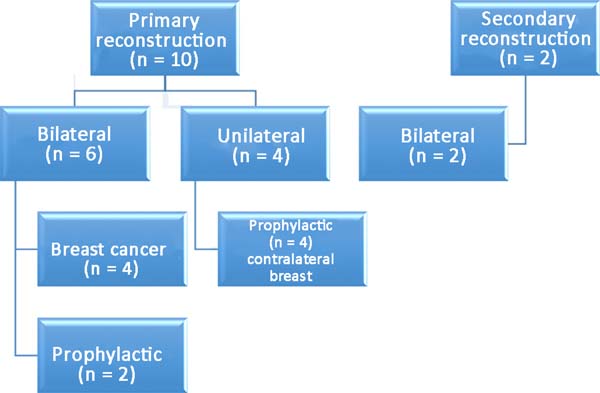

Among the patients, 83% (n=10) underwent primary breast reconstruction and 17%

(n=2) underwent secondary breast reconstruction (Figure 6). The secondary reconstructions were performed in patients

who had undergone conservative surgery for breast cancer with adjuvant

radiotherapy and who exhibited severe asymmetry. Bilateral reconstructions

accounted for 66% (n=8) of the cases, whereas unilateral reconstructions

comprised 34% (n=4) of the cases. Considering only the bilateral

reconstructions, 75% (n=6) were primary and 25% (n=2) were secondary

reconstructions. Of the bilateral primary reconstructions, 66% (n=4) were

NAC-sparing mastectomies for breast cancer and 34% (n=2) were prophylactic

mastectomies in patients with the BRCA1 gene mutation.

Figura 6 - Distribution of patients according to the type of

reconstruction.

Figura 6 - Distribution of patients according to the type of

reconstruction.

In patients with the gene mutation, prophylactic adenomastectomy was associated

with videolaparoscopic bilateral oophorectomy. The mean duration of unilateral

surgeries was 100 minutes (80-120 min), while that of bilateral surgeries was

180 minutes (100-240 min). The mean volume of the used implants was 345 mL

(270-415 mL). The mean duration of hospitalization was 36 hours (12-72 h). The

mean time of drain use was 12.2 days.

The complications are listed in Table 2.

Three breasts (15%) had minor complications. One patient (5%) had a hematoma of

moderate volume in the immediate postoperative period, which was treated

conservatively with drainage in an outpatient setting. Another patient exhibited

rippling at six months postoperatively, with spontaneous

improvement after 12 months (Figures 7 and

8). Lastly, one patient had

epidermolysis and suture dehiscence after unilateral adenomastectomy and breast

reconstruction with implant and mesh. This patient was treated with surgical

debridement and resuture because she resided in a different city and was not

able to attend frequent follow-ups.

Table 2 - Postoperative complications.

| |

20 breasts |

| Infection |

0 |

| Flap necrosis |

0 |

| NAC necrosis |

0 |

| Suture dehiscence |

n = 1 (5%) |

| Hematoma |

n = 1 (5%) |

| Rippling |

n = 1 (5%) |

| Seroma |

0 |

| Capsular contracture |

0 |

| Total |

3 (15%) |

Table 2 - Postoperative complications.

Figure 7 - Six-month follow-up of a 47-year-old patient who underwent

prophylactic left adenomastectomy after right mastectomy for

invasive ductal carcinoma, with visible rippling in the left

breast.

Figure 7 - Six-month follow-up of a 47-year-old patient who underwent

prophylactic left adenomastectomy after right mastectomy for

invasive ductal carcinoma, with visible rippling in the left

breast.

Figure 8 - Twelve-month follow-up of a 47-year-old patient who underwent

prophylactic left adenomastectomy after right mastectomy for

invasive ductal carcinoma. Note the improvement of rippling.

Figure 8 - Twelve-month follow-up of a 47-year-old patient who underwent

prophylactic left adenomastectomy after right mastectomy for

invasive ductal carcinoma. Note the improvement of rippling.

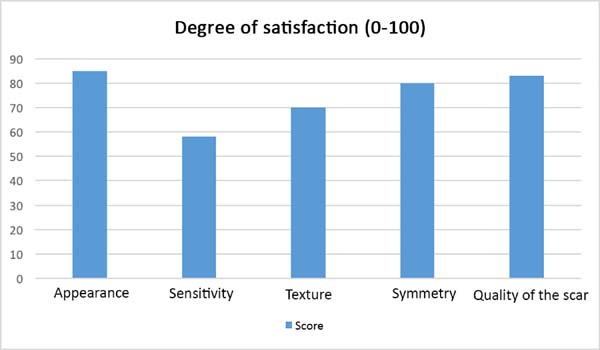

After the sixth month postoperatively, the patients answered the questionnaire

regarding their degree of satisfaction. The mean score for satisfaction with

breast appearance was 85 points. Sensitivity (58 points), texture (70 points),

symmetry (80 points), and scar quality (83 points) were also scored. The overall

mean was 75.2 points (Figure 9). Only one

patient (6%) responded “maybe” when asked whether she would opt for a different

surgical technique.

Figure 9 - Patient degree of satisfaction after the surgical procedure with

regard to the 5 parameters.

Figure 9 - Patient degree of satisfaction after the surgical procedure with

regard to the 5 parameters.

DISCUSSION

The benefits of immediate breast reconstruction have been proven with regard to

improved quality of life in mastectomy patients, especially among young

women14. Indeed, the level of

psychosocial stress caused by the feeling of mutilation is alleviated in

patients who undergo immediate reconstruction8.

The major advantage of immediate reconstruction with implants is that it is

performed in a single stage, which means less patient morbidity and reduced

costs. However, rigorous patient selection is mandatory to achieve a good

cosmetic result after surgery. The decision to perform immediate reconstruction

should be multifactorial and should consider important preoperative factors such

as the patient’s oncological status, presence of comorbidities, smoking, and

previous history of mammoplasty, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or radiotherapy15.

Assessment of the mastectomy flap is another critical factor in the success of

the surgery. This assessment may be performed clinically by analyzing patterns

of ischemia or through studies of intraoperative imaging16. When intraoperative adjuvant radiotherapy is indicated,

two-stage reconstruction with an expander should be selected, since irradiation

of the implants is associated with increased complications17.

The success of the cosmetic result of immediate reconstructions with implants

also hinges on the evolution of mastectomy surgical techniques, in particular

skin-sparing and NAC-sparing mastectomies. The primary indications for this type

of approach include prophylactic mastectomy or early-stage tumors; however, the

spectrum of indications has been increasing. In the context of the appropriate

indication, immediate reconstruction has been shown to be associated with a low

rate of complications and good oncologic safety, even in patients with locally

advanced tumors who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy18.

The use of acellular dermal matrices in breast reconstruction has allowed

surgeons to obtain better cosmetic results as a result of less musculofascial

dissection, better control of the inframammary fold with projection of the lower

pole, and expansion of the submuscular pocket, which permits the safe use of

larger implants19.

Despite these benefits, the use of acellular dermal matrices in Brazil is still

restricted by the policies governed by Anvisa, which forbid the use of human

(cadaveric) biological material in other patients. Dermal matrices of animal

origin (porcine or bovine) are an alternative that yields similar results20, but their use is limited by their high

cost. In general, it is estimated that the use of matrices is 8 to 10 times more

expensive than that of meshes. Therefore, the use of a synthetic material that

mimics biological matrices is being advocated with the aim of obtaining optimal

aesthetic results.

In the present study, a partially absorbable, lightweight mesh made of synthetic

materials, namely Prolene (polypropylene) and Monocryl (poliglecaprone), was

used. The Monocryl portion is absorbed within 90-120 days and becomes

incorporated into the tissue. The use of synthetic meshes in plastic surgery is

not novel. In fact, many authors in Brazil have published studies on the

subject, with a large number of citations pertaining to methods of mastopexy

with mesh support21,22. The use of this synthetic material in

breast reconstruction is also not new and has been shown to be a very safe

technique with a low rate of complications, despite some technical differences

between the published articles23,24.

The rigorous selection of appropriate patients is required for the success of the

surgical technique. In the present study, 12 consecutive patients with a

postoperative follow-up of at least six months were selected. Although obesity,

smoking, and history of radiation may increase the risk of complications from

this procedure15, a multivariate analysis

of the patients’ characteristics as risk factors for complications was not

performed owing to the small size of the sample. However, in the study cohort,

the factors of the patients’ medical conditions, history of mammoplasty, and

smoking appeared to have minimally impacted the rate of complications, with the

viability of the mastectomy flap being the primary factor linked to the

occurrence of epidermolysis and suture dehiscence.

The patients who underwent bilateral prophylactic adenomastectomy had a strong

family history and BRCA1 gene mutation, and breast reconstruction in combination

with videolaparoscopic bilateral oophorectomy was indicated. In addition, the

association of an abdominal surgery did not appear to increase complications,

even with an increased duration of surgery.

All patients who underwent unilateral procedures with this technique had

undergone previous mastectomy and breast reconstruction with an expander or

flap. During the exchange of the expander for the definitive implant or in a

second stage, when indicated, these patients underwent contralateral

prophylactic adenomastectomy and reconstruction with the technique in question.

The patient who progressed to suture dehiscence and required reoperation was

included in this group. In cases of prophylactic surgery, given the absence of

local disease, it is essential to ensure that the mastectomy flap has an

adequate thickness to avoid ischemic complications.

The patients who underwent secondary reconstruction exhibited the same profile,

i.e., they had undergone conservative surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy and

exhibited significant asymmetry. However, one patient had undergone

reconstruction with implants at the time and progressed to capsular contracture

in addition to asymmetry (Figures 10 to

13).

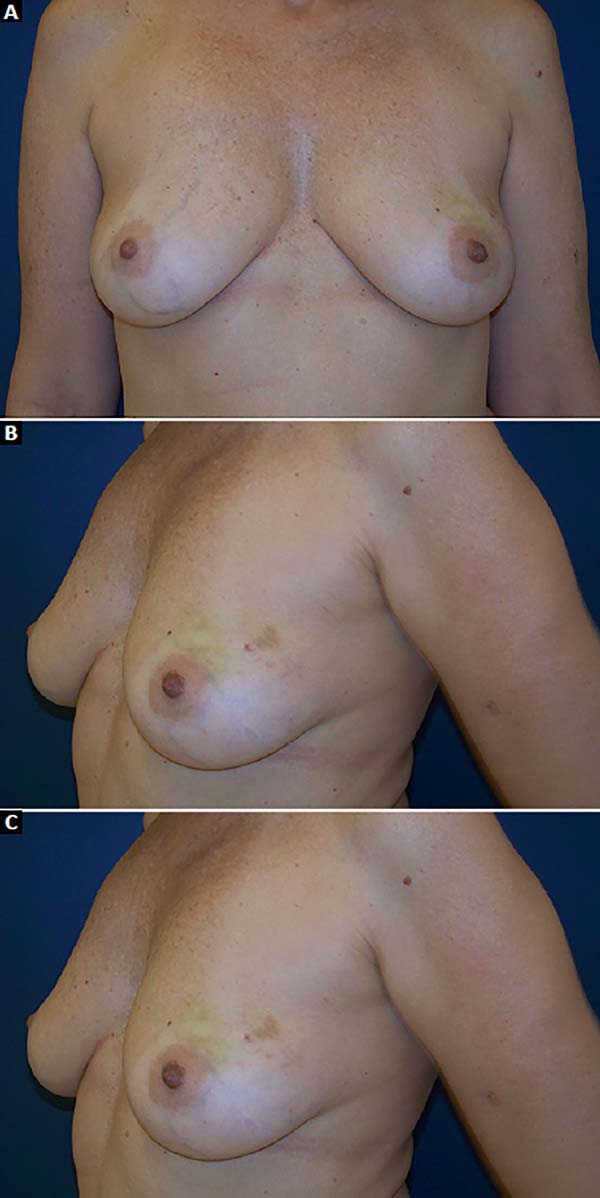

Figure 10 - Preoperative view of a 52-year-old patient who underwent

conservative surgery for invasive ductal carcinoma in the left

breast 10 years ago with significant asymmetry.

Figure 10 - Preoperative view of a 52-year-old patient who underwent

conservative surgery for invasive ductal carcinoma in the left

breast 10 years ago with significant asymmetry.

Figure 11 - Postoperative view (6 months) of a 52-year-old patient after

bilateral breast reconstruction with implant, mesh, and fat

graft.

Figure 11 - Postoperative view (6 months) of a 52-year-old patient after

bilateral breast reconstruction with implant, mesh, and fat

graft.

Figure 12 - Preoperative view of a 47-year-old patient who underwent

conservative surgery for ductal in situ carcinoma

in the left breast 8 years ago with significant asymmetry and

capsular contracture.

Figure 12 - Preoperative view of a 47-year-old patient who underwent

conservative surgery for ductal in situ carcinoma

in the left breast 8 years ago with significant asymmetry and

capsular contracture.

Figure 13 - Postoperative view (6 months) of a 47-year-old patient after

bilateral breast reconstruction with implant, mesh, and fat

graft.

Figure 13 - Postoperative view (6 months) of a 47-year-old patient after

bilateral breast reconstruction with implant, mesh, and fat

graft.

Another factor that is essential to reduce complications is the location of the

incisions. This should be discussed and planned based on the mastologist’s

experience, tumor location (in the case of cancer), and presence or absence of

previous scars. In the present study, there were incisions along the submammary

fold, comma-shaped inferior incisions (Figure 14), periareolar incisions with lateral extension (Figure 15), and classical mammoplasty

incisions.

Figura 14 - Comma-shaped incision.

Figura 14 - Comma-shaped incision.

Figura 15 - Superior periareolar incision with lateral extension.

Figura 15 - Superior periareolar incision with lateral extension.

Incisions that involve the areola appear to be more associated with ischemic

complications of the NAC25. Thus,

patients at higher risk of NAC necrosis after mastectomy, such as smokers or

patients with previous mammoplasty, may undergo areola autonomization in an

outpatient setting26 to improve local

vascularization. However, no patient in the present study underwent this

procedure. It is very important that the mastectomy flap is well vascularized,

especially when incisions are made to elevate the NAC.

One of the main complaints of patients in the postoperative period is pain, which

is primarily caused by the major musculofascial dissection. Therefore, the aim

of using intramuscular bupivacaine was to control pain and reduce the need for

opioids postoperatively. Although the results of using liposomal bupivacaine are

promising27, its use is still not

permitted in Brazil. Recent studies analyzing immediate breast reconstruction

with implants covered by dermal matrices in the prepectoral position also aimed

to reduce postoperative pain as well as complications such as hyper-animation

deformity, but they remain very controversial28.

Despite the small size of the study sample, the rate of complications of

reconstruction surgery with implants and mesh was similar to that observed in

other large series29,30. The degree of satisfaction of the

patients was measured using a visual analog scale comprising 5 parameters. While

the best method for assessing the patients’ degree of satisfaction in terms of

quality of life after breast reconstruction is a validated and translated

questionnaire, such as the Breast-Q31, it

is a long questionnaire that patients have difficulty completing in the private

clinic setting. Therefore, it was not used in the present study.

The patients were primarily dissatisfied with the sensitivity; however, because

the questionnaire was administered at six months postoperatively, these patients

would likely report some degree of improvement in a later follow-up. Although

the parameter “texture” had a good satisfaction score in the questionnaire, some

patients reported feeling the surface of the mesh, especially in thin flaps.

However, this complaint was not frequent after the period of absorption of the

PDS thread, which is used in the fixation of the mesh to the muscle wall, and of

the Monocryl portion of the mesh. The patients’ degree of satisfaction with the

cosmetic result also scored well, which validates the continued application of

the technique (Figures 16 to 19).

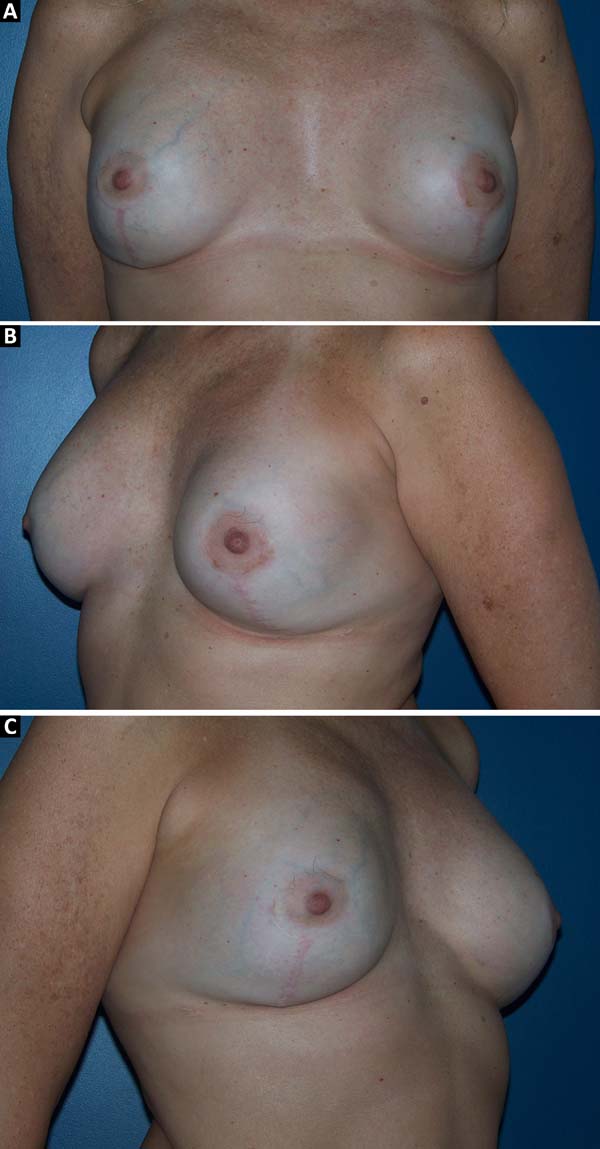

Figure 16 - Preoperative view of a 47-year-old patient with a history of

ductal carcinoma in situ in the left breast.

A: Frontal view; B: Left oblique view;

C: Right oblique view.

Figure 16 - Preoperative view of a 47-year-old patient with a history of

ductal carcinoma in situ in the left breast.

A: Frontal view; B: Left oblique view;

C: Right oblique view.

Figure 17 - Postoperative view (6 months) of a 47-year-old patient who

underwent bilateral breast reconstruction with implant and mesh.

A: Frontal view; B: Left oblique view;

C: Right oblique view.

Figure 17 - Postoperative view (6 months) of a 47-year-old patient who

underwent bilateral breast reconstruction with implant and mesh.

A: Frontal view; B: Left oblique view;

C: Right oblique view.

Figure 18 - Preoperative view of a 53-year-old patient with a history of

invasive ductal carcinoma in the right de breast.

Figure 18 - Preoperative view of a 53-year-old patient with a history of

invasive ductal carcinoma in the right de breast.

Figure 19 - Postoperative view (6 months) of a 53-year-old patient with a

history of invasive ductal carcinoma in the right breast who

underwent reconstruction with latissimus dorsi muscle flap and

implant in the right breast and prophylactic adenomastectomy and

reconstruction with implant and mesh in the left breast.

Figure 19 - Postoperative view (6 months) of a 53-year-old patient with a

history of invasive ductal carcinoma in the right breast who

underwent reconstruction with latissimus dorsi muscle flap and

implant in the right breast and prophylactic adenomastectomy and

reconstruction with implant and mesh in the left breast.

Although this was a retrospective study with a small number of cases, the results

demonstrated that the proposed reconstruction technique with implants and mixed

mesh has a lower rate of complications compared to other techniques of immediate

reconstruction with implants with total muscle coverage or the use of dermal

matrices.

Studies on the placement of implants with total muscle coverage indicate

complication rates of up to 40%, including mainly implant malposition, asymmetry

of the submammary fold, and capsular contracture30. Therefore, the limitations of this technique are based on the

small size of the submuscular pocket, which prevents the placement of larger

implants and hinders the creation of a natural breast and a defined submammary

fold. The use of a mesh helps to enlarge the pocket and allows for better

control of the implant positioning, as well as greater expansion of the lower

pole of the breast.

A prospective, randomized, and controlled study is necessary to compare the use

of mesh with that of acellular dermal matrices, including an assessment of

cost-effectiveness. Matrix-related complications are usually associated with

infection and seroma, with rates ranging between 6% and 29%32,33. In

the present study, the complications were minor and occurred at a rate of

15%.

CONCLUSION

The proposed breast reconstruction technique using implants and synthetic mesh

was found to be associated with a low rate of complications, a high degree of

patient satisfaction with the cosmetic result, and a lower cost relative to the

use of acellular dermal matrices. However, rigorous patient selection, careful

incision planning, and a well-vascularized flap after mastectomy are extremely

critical factors for the success of the surgical procedure.

COLLABORATIONS

|

DGL

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final

approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study;

completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript

or critical review of its contents.

|

REFERENCES

1. Halsted WS. I. The Results of Radical Operations for the Cure of

Carcinoma of the Breast. Ann Surg. 1907;46(1):1-19. PMID:

17861990

2. Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER,

et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy,

lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast

cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1233-41. PMID: 12393820 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa022152

3. Al-Ghazal SK, Fallowfield L, Blamey RW. Comparison of psychological

aspects and patient satisfaction following breast conserving surgery, simple

mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(15):1938-43. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(00)00197-0

4. Taylor GI. The angiosomes of the body and their supply to perforator

flaps. Clin Plast Surg. 2003;30(3):331-42. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0094-1298(03)00034-8

5. Reuben BC, Manwaring J, Neumayer LA. Recent trends and predictors in

immediate breast reconstruction after mastectomy in the United States. Am J

Surg. 2009;198(2):237-43. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2008.11.034

6. Alderman AK, Wei Y, Birkmeyer JD. Use of breast reconstruction after

mastectomy following the Women's Health and Cancer Rights Act. JAMA.

2006;295(4):387-8. PMID: 16434628

7. Brasil. Governo Federal. Ministério da Saúde. Lei Nº 9.797, de 6 de

maio de 1999. Alterada pela Lei Federal 12.802, de 24/04/2013. Dispõe sobre a

obrigatoriedade da cirurgia plástica reparadora da mama pela rede de unidades

integrantes do Sistema Único de Saúde - SUS nos casos de mutilação decorrentes

de tratamento de câncer. Brasília: Governo Federal; 2013.

8. Zhong T, Hu J, Bagher S, Vo A, O'Neill AC, Butler K, et al. A

Comparison of Psychological Response, Body Image, Sexuality, and Quality of Life

between Immediate and Delayed Autologous Tissue Breast Reconstruction: A

Prospective Long-Term Outcome Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(4):772-80.

PMID: 27673514 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002536

9. Albornoz CR, Bach PB, Mehrara BJ, Disa JJ, Pusic AL, McCarthy CM, et

al. A paradigm shift in U.S. Breast reconstruction: increasing implant rates.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(1):15-23. PMID: 23271515 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182729cde

10. Munhoz AM, Aldrighi CM, Montag E, Arruda EG, Aldrighi JM, Gemperli

R, et al. Clinical outcomes following nipple-areola-sparing mastectomy with

immediate implant-based breast reconstruction: a 12-year experience with an

analysis of patient and breast-related factors for complications. Breast Cancer

Res Treat. 2013;140(3):545-55. PMID: 23897416 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10549-013-2634-7

11. Macadam SA, Lennox PA. Acellular dermal matrices: Use in

reconstructive and aesthetic breast surgery. Can J Plast Surg. 2012;20(2):75-89.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/229255031202000201

12. Maxwell GP, Gabriel A. Use of the acellular dermal matrix in

revisionary aesthetic breast surgery. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29(6):485-93. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.asj.2009.09.007

13. Shulman AG, Amid PK, Lichtenstein IL. The safety of mesh repair for

primary inguinal hernias: results of 3,019 operations from five diverse surgical

sources. Am Surg. 1992;58(4):255-7. PMID: 1586085

14. Dauplat J, Kwiatkowski F, Rouanet P, Delay E, Clough K, Verhaeghe

JL, et al.; STIC-RMI working group. Quality of life after mastectomy with or

without immediate breast reconstruction. Br J Surg. 2017;104(9):1197-206. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/bjs.10537

15. Tang R, Coopey SB, Colwell AS, Specht MC, Gadd MA, Kansal K, et al.

Nipple-Sparing Mastectomy in Irradiated Breasts: Selecting Patients to Minimize

Complications. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3331-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1245/s10434-015-4669-y

16. Gurtner GC, Jones GE, Neligan PC, Newman MI, Phillips BT, Sacks JM,

et al. Intraoperative laser angiography using the SPY system: review of the

literature and recommendations for use. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2013;7(1):1. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1750-1164-7-1

17. Kronowitz SJ, Robb GL. Radiation therapy and breast reconstruction:

a critical review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):395-408.

PMID: 19644254 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee987

18. Coopey SB, Tang R, Lei L, Freer PE, Kansal K, Colwell AS, et al.

Increasing eligibility for nipple-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol.

2013;20(10):3218-22. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1245/s10434-013-3152-x

19. Vardanian AJ, Clayton JL, Roostaeian J, Shirvanian V, Da Lio A, Lipa

JE, et al. Comparison of implant-based immediate breast reconstruction with and

without acellular dermal matrix. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128(5):403e-410e.

PMID: 22030500

20. Glasberg SB, Light D. AlloDerm and Strattice in breast

reconstruction: a comparison and techniques for optimizing outcomes. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(6):1223-33. PMID: 22327891 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824ec429

21. Sampaio Góes JC. Periareolar mammaplasty: double-skin technique with

application of mesh support. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29(3):349-64. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0094-1298(02)00005-6

22. Bozola AR. Mamoplastia pós-cirurgia bariátrica usando suporte

protético complementar de contenção glandular. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2016;31(3):299-307.

23. Tessler O, Reish RG, Maman DY, Smith BL, Austen WG Jr. Beyond

biologics: absorbable mesh as a low-cost, low-complication sling for

implant-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(2):90e-9e.

PMID: 24469217 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000437253.55457.63

24. Pukancsik D, Kelemen P, Gulyás G, Újhelyi M, Kovács E, Éles K, et

al. Clinical experiences with the use of ULTRAPRO® mesh in single-stage

direct-to-implant immediate postmastectomy breast reconstruction in 102

patients: A retrospective cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43(7):1244-51.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ejso.2017.01.236

25. Rawlani V, Fiuk J, Johnson SA, Buck DW 2nd, Hirsch E, Hansen N, et

al. The effect of incision choice on outcomes of nipple-sparing mastectomy

reconstruction. Can J Plast Surg. 2011;19(4):129-33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/229255031101900410

26. Jensen JA, Lin JH, Kapoor N, Giuliano AE. Surgical delay of the

nipple-areolar complex: a powerful technique to maximize nipple viability

following nipple-sparing mastectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(10):3171-6. DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1245/s10434-012-2528-7

27. Leiman D, Barlow M, Carpin K, Piña EM, Casso D, et al. Medial and

lateral pectoral nerve block with liposomal bupivacaine for the management of

postsurgical pain after submuscular breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg

Glob Open. 2015;2(12):e282.

28. Sigalove S, Maxwell GP, Sigalove NM, Storm-Dickerson TL, Pope N,

Rice J, et al. Prepectoral Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction: Rationale,

Indications, and Preliminary Results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(2):287-94.

DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002950

29. Baldelli I, Cardoni G, Franchelli S, Fregatti P, Friedman D, Pesce

M, et al. Implant-Based Breast Reconstruction Using a Polyester Mesh

(Surgimesh-PET): A Retrospective Single-Center Study. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2016;137(6):931e-9e. PMID: 27219260 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002180

30. Meyer Ganz O, Tobalem M, Perneger T, Lam T, Modarressi A, Elias B,

et al. Risks and benefits of using an absorbable mesh in one-stage immediate

breast reconstruction: a comparative study. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2015;135(3):498e-507e. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000001027

31. Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, Klok JA, Cordeiro PG, Cano SJ.

Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the

BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(2):345-53. PMID: 19644246 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807

32. Chun YS, Verma K, Rosen H, Lipsitz S, Morris D, Kenney P, et al.

Implant-based breast reconstruction using acellular dermal matrix and the risk

of postoperative complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125(2):429-36. PMID:

20124828 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181c82d90

33. Lanier ST, Wang ED, Chen JJ, Arora BP, Katz SM, Gelfand MA, et al.

The effect of acellular dermal matrix use on complication rates in tissue

expander/implant breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64(5):674-8. PMID:

20395795

1. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil.

2. Américas Centro de Oncologia Integrado, Rio de

Janeiro, RJ, Brazil.

3. Hospital Federal de Ipanema, Rio de Janeiro,

RJ, Brazil.

*Corresponding author: Daniel Gouvea Leal, Rua

Redentor, 26 - Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. Zip Code 22421-030. E-mail:

danileal.rlk@terra.com.br

Article received: June 5, 2017.

Article accepted: August 7, 2017.

Conflicts of interest: none.