INTRODUCTION

Trauma injuries to the hand are a frequent reason for emergency room visits. Dislocations

of the metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP) of the long fingers are rare and serious injuries,

given the connective tissue support present around this joint and its basal position

in the hand1,2. Joint stability is enhanced by bilateral attachments of the deep, transverse metacarpal

ligaments, which unite and stabilize the palmar plate. This intimate relationship

provides stability but is also responsible for the irreducibility of the lesion. The

index and little fingers do not have this bilateral support and, therefore, are more

prone to injuries3.

Dislocations are classified as simple when closed reduction is possible, with the

volar plate remaining fixed to the proximal phalanx in these cases and the finger

being highly hyperextended in the resting position (60 to 90º); or complex when reduction

by closed methods is not possible due to the interposition of periarticular structures,

and its clinical presentation is even rarer4. Most authors agree that the volar plate is the reason for the impossibility of closed

reduction of these lesions5,6.

Clinically, they present with the metacarpophalangeal joint slightly hyperextended

(30-40º) and the interphalangeal joints slightly flexed, adding to palpation of the

metacarpal head (MTP) at the volar level and decreased range of motion of the MCP.

It is important to distinguish between a simple and a complex dislocation because

their approach and treatment are different.

Simple dislocations (or subluxations) can be treated non-surgically by closed reduction,

while attempts at a closed reduction in complex dislocations are often unsuccessful

and often lead to additional complications. Open surgical reduction is the method

of choice in these injuries, allowing joint anatomical recovery with the lowest risk

of complications.

Adequate treatment and knowledge of hand injuries are extremely important, conditioning

the patient’s functional prognosis and limiting the impact and health costs of a long

absence from work. It is essential to determine the best treatment to achieve full

hand functionality recovery and return to work as soon as possible, emphasizing that

this type of injury occurs, in its vast majority, in the working population.

OBJECTIVE

The present study aims to update the clinical and therapeutic approach, analyzing

the advantages and disadvantages of the different surgical techniques used in treating

complex dislocations based on a clinical case operated by the author.

METHODS

A narrative review of the literature on dorsal metacarpophalangeal dislocation of

the long fingers of the hand was performed. The search was performed in Medline (Pubmed

interface), SciELO and Google Scholar databases. The keywords were used: “metacarpophalangeal

joint,” “dislocation,” “open reduction,” and “volar plate.”

Abstracts of articles from the first search were analyzed by the authors, selecting

publications that met the following inclusion criteria: clinical trials, case series,

case reports and literature reviews that included patients diagnosed with dorsal metacarpophalangeal

dislocation of long fingers, articles published in English, Spanish and Portuguese

and no restrictions were established regarding the time of publication.

Exclusion criteria were: metacarpophalangeal dislocation of the first finger and publications

without an identifiable scientific article format.

A clinical case operated by the author is presented, which was evaluated in the emergency

department of the Hospital de Clínicas de Montevideo - Uruguay, from June to December

2020.

This work is carried out following the guidelines of the Ethics Committee of Hospital

de Clínicas, approval number 32. The images of patients in this publication have informed

consent.

CLINICAL CASE

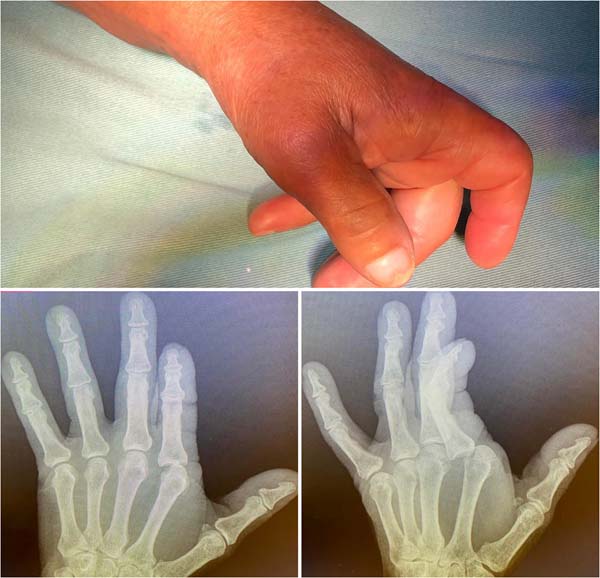

Female patient, 52 years old, right-handed, presented a fall from her height on her

left hand in extension. She consulted the emergency room 12 hours after the trauma.

The energetic hyperextension determined a complex dorsal dislocation of the metacarpophalangeal

joint of the second finger of the left hand, presenting in the emergency with a pathological

attitude, with the MCP joint in 30º of extension and the interphalangeal joints slightly

flexed, with the impossibility of joint mobilization of the second ray (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Clinical presentation in the emergency. A) Clinical presentation in the emergency

room: metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP) hyperextended to 30º and slightly flexed interphalangeal

joint. B and C) Plain radiographs: anteroposterior view showing ulnar displacement

of the proximal phalanx and enlargement of the joint space. Oblique radiography confirms

dorsal displacement of the proximal phalanx.

Figure 1 - Clinical presentation in the emergency. A) Clinical presentation in the emergency

room: metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP) hyperextended to 30º and slightly flexed interphalangeal

joint. B and C) Plain radiographs: anteroposterior view showing ulnar displacement

of the proximal phalanx and enlargement of the joint space. Oblique radiography confirms

dorsal displacement of the proximal phalanx.

Hand radiographs confirmed the dislocation described without showing the presence

of an interposed sesamoid (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Intraoperative images. Classic appearance in volar exposure: the metacarpal head (MTP)

is observed with the flexor tendon towards the ulnar and lumbricals towards the radial.

The A1 (A1) pulley is observed in the ulnar and distal sectors before its necessary

cut for reduction. The radial digital nerve (RN) is radially reclined from the metacarpal

head.

Figure 2 - Intraoperative images. Classic appearance in volar exposure: the metacarpal head (MTP)

is observed with the flexor tendon towards the ulnar and lumbricals towards the radial.

The A1 (A1) pulley is observed in the ulnar and distal sectors before its necessary

cut for reduction. The radial digital nerve (RN) is radially reclined from the metacarpal

head.

A closed reduction attempt was made under a regional wrist block without therapeutic

success, so open reduction was coordinated in the operating room under general anesthesia.

It was performed in a closed field with a pneumatic cuff, volar approach through sinusoidal

insertion centered on the head of the second metacarpal. The characteristic findings

of these lesions were identified: disinserted proximal volar plate, interposed and

blocking the joint, radial collateral nerve in close relationship with the metacarpal

head, which was identified and protected during surgery, and displacement of the flexor

to ulnar and lumbrical towards the radial, producing a loop around the head of the

second MTP. Longitudinal sectioning of the A1 pulley and volar plate was performed

to restore normal joint anatomy. Figure 3 shows the normal attitude of the hand after reduction. There were no intra or postoperative

complications.

Figure 3 - Immediate postoperative period. Clinical presentation in front and profile. Correction

of the typical pathological attitude of these lesions is seen.

Figure 3 - Immediate postoperative period. Clinical presentation in front and profile. Correction

of the typical pathological attitude of these lesions is seen.

Immobilization was performed with a locked dorsal brachydigital splint for two weeks,

followed by rehabilitation by occupational therapy consisting of passive and active

range of motion exercises and complementary therapies to control edema and optimize

the healing process. The patient had a good evolution, recovering to the full range

of motion at eight weeks.

DISCUSSION

The pathogenesis and anatomy of these lesions were initially reported by Kaplan7 in 1957, who described that the various structures involved contribute to the irreducibility

of dislocation by closed methods. In 1876, Farabeuf described its management and treatment

based on the description of MCP dislocations of the thumb8.

Dorsal metacarpophalangeal dislocations of the long fingers usually occur in patients

with a history of trauma from a fall with an outstretched hand with the finger in

hyperextension. They can occur in all MCP joints, being more frequent in the external

fingers2,4 due to their greater vulnerability to trauma and the lack of stabilization by the

adjacent deep, transverse metacarpal ligaments. Most of the reports found in the literature

are from the index finger; among these, less than 10% are open9.

Dislocations are classified as simple when closed reduction is possible; in these

cases, the volar plate remains fixed in the proximal phalanx, and the finger is highly

hyperextended in the resting position (60 to 90º); or complex when reduction by closed

methods is not possible, due to the interposition of periarticular structures, and

its clinical presentation is less frequent2,4.

It is important to distinguish between a simple and a complex dislocation because

their approach and treatment are different. Simple dislocations (or subluxations)

can be treated non-surgically by closed reduction. The maneuver is performed by gently

flexing the wrist to relax the flexor tendons and then applying gradual dorsal-to-volar

pressure on the dorsal base of the proximal phalanx, flexing the MCP10 joint. Longitudinal traction instead of force applied based on the first phalanx

can transform a simple displacement into a complex one, making it irreducible and

injuring adjacent structures, which can lead to degenerative arthritis, with a decrease

in the final range of motion8,10-12.

Complex dislocations are those cases in which the volar plate detaches from its junction

with the metacarpal and is interposed between the proximal phalanx and this phalanx2,4,13. It has been reported that the metacarpal head can become trapped between adjacent

tendon structures. In the case of the index finger, the flexors move ulnarly, and

the lumbricals move radially; in the fifth finger, the abductor tendon and the flexor

brevis of the fifth finger move ulnarly and the lumbricals move radially2,4. The swimming ligament can move dorsally, and the superficial transverse metacarpal

ligament proximally7.

Clinically, they present with the metacarpophalangeal joint slightly hyperextended

(30-40º) and the interphalangeal joints slightly flexed secondary to the dorsal displacement

of the proximal phalanx, palpation of the MTP head at the volar level and decreased

range of motion of the MCP11. It can also be accompanied by a slight deviation in the anteroposterior plane, in

the case of the index finger, towards the ulnar14. The wrinkling of the palmar skin on the metacarpal head is recognized as a pathognomonic

sign, which can also associate skin wounds with exposure to the metacarpal head5.

At the time of trauma, the hyperextension force determines the rupture of the weakest

membranous portion of the palmar plate at its insertion into the metacarpal, which

determines its displacement to be stuck in the joint2.

Regarding the paraclinical, frontal, lateral and oblique radiographs should be requested.

An anteroposterior radiograph usually shows an increase in joint space and a displacement

of the base of the phalanx in an ulnar direction. The presence of an interposed sesamoid

within the joint, usually moving distally and ulnarly from the joint, is a characteristic

finding in the diagnosis of volar plate entrapment and seals the closed irreducibility

of these lesions.

Generally, they are better visualized in the oblique approach8,11,14,15. In these cases, Kaplan defined the treatment as “triple release,” adding the extraction

of the volar plate from the joint with the sesamoid. These bones are present in approximately

70% of the population; they appear to cover the MTP head at 12 years of age. Generally,

they are single on the second and third MTP and can be bent on the first, fourth and

fifth rays14.

In the lateral approach to radiography, the base of the proximal phalanx is dorsal

to the metacarpal head and may or may not associate osteochondral fractures in the

dorsal head of the same.

Complex dislocations require surgical treatment through an approach that can be volar,

dorsal, lateral or combined16.

The need for surgical reduction is due to the region’s anatomy, which contributes

to its complexity and difficulty.

Kaplan described the structures responsible for the irreducible nature of the dislocation,

such as the superficial and deep, transverse metacarpal ligaments, the swimming ligament,

the flexor and the lumbrical tendons3,7.

The deep, transverse metacarpal ligament plays a key role in MCP joint stability.

They are closely linked to the volar plate, and together they constitute the most

relevant structures in irreducibility8,15,17. This ligament, which is tense on the dorsum of the dislocated metacarpal head, acts

as a mechanical block, holding the joint in place and making it impossible to reduce.

Gerrand & Shearer15, in their review of the case, proposed a reduction to release the remaining union

of the volar plate with the transverse metacarpal ligament, preserving its distal

insertion in the neck of the proximal phalanx.

As a characteristic finding, the metacarpal head is trapped between adjacent structures:

flexors and lumbricals, and the volar plate detach from its proximal insertion in

the neck of the MTP. It is systematically displaced to be searched in the dorsal joint

space in the MTP head, which acts as a mechanical obstruction in closed reduction2,14.

The closed reduction maneuver in these cases employing traction is usually insufficient

and generates a loop for the metacarpal head, producing more trauma to the adjacent

tissues. Some authors recommend, even after the diagnosis of dislocation, avoiding

closed maneuvers and opting for open reduction as the first treatment option5,14,15.

In their systematic review, Diaz Abele et al.1 recommended reducing closed reduction attempts in the preoperative period and performing

open reduction with minimal delay. Previous attempts at reduction are potentially

traumatic and can lead to further damage to the joint surfaces and even the creation

of a cord around the metacarpal head due to excessive traction. Surgery usually requires

a volar plate cut, and the authors recommend repair with figure-eight stitches and

subsequent immobilization with a dorsal block splint for two weeks, followed by rehabilitation

by the occupational therapy team.

Open reduction is performed in a surgical center under regional or general anesthesia,

with a bloodless field, under a pneumatic cuff that allows for a correct balance of

the lesion and the correct identification of injured structures. Currently, the safety

of using local anesthesia with epinephrine in hand surgery is well known, which provides

anesthesia and a bloodless field through vasoconstriction, eliminating the need for

a pneumatic tourniquet and general anesthesia18.

There are controversies regarding the most appropriate surgical approach for reduction.

In his initial description, Kaplan defends the volar approach, like other authors2,5,9,15. This approach allows direct access to the lesion and subsequent anatomical restoration

of the joint, possibly repairing the volar plate. This may be related to a lower risk

of late instability2.

It is performed through a zigzag or sinusoidal skin incision, which allows distal

and proximal extension over the MCP joint11,15. Care must be taken with the radial collateral nerve and artery in injuries to the

second and third fingers and with the ulnar collateral nerve and artery in injuries

to the fourth and fifth fingers2,15. Neurovascular damage can be avoided by careful dissection and more atraumatic tissue

management.

For reduction, some authors3 refer to the need to section the remaining union of the deep, transverse ligament

attached to the palmar plate and incise the superficial and transverse swimming ligaments.

Releasing the A1 pulley decreases the tension of the loop around the metacarpal. The

proximal phalanx and volar plate can usually be repositioned into their anatomical

positions by relieving tension on the tendon.

If necessary, the palmar plate5,7 can also be released and minimal traction applied to the flexor tendons to perform

the reduction maneuver by moving the MTP head dorsally and making a slight flexion

of the joint from ulnar to radial, flexing the phalanx proximal.

Some authors1,2,14,15 repair the palmar plate with figure-eight stitches with non-absorbable sutures after

the maneuver, and others do not, justifying that the periarticular structures limit

the risk of posterior instability6.

In their review, Diaz Abele et al.1 reported better results when repairing it, having the greatest active metacarpophalangeal

range of motion in these cases. In cases where bone fixation of the palmar plate was

performed, a worse result was obtained regarding the joint range of motion in the

postoperative period. Gerrand & Shearer15, in their review of the case, performed the suture of the volar plate to the periosteum

of the metacarpal in the proximal direction.

The authors who defend the dorsal approach17,19,20 among its advantages highlight the good exposure of the volar plate and the low risk

of injury to the digital nerves. This approach is also useful in those dislocations

associated with osteochondral fractures of the metacarpal head that may require fixation

or excision of the fragment depending on its size. The main disadvantage is that the

volar plate, which is split longitudinally for reduction, cannot be repaired by this

approach.

O’Neill et al.21, in their case report published in 2021, used a dorsal approach, obtaining good results

with an early functional return one month after the injury, despite the delay in definitive

treatment. A centralized incision is made over the joint, and the extensor tendon

and joint capsule must be sectioned longitudinally. The volar plate that appears immediately

interposed is also sectioned longitudinally to subsequently perform reduction by flexing

the wrist and finger.

Barry et al.17, in their study combining their clinical experience with the dissection of anatomical

samples from cadaver hands, compared the volar and dorsal approaches. In cadaveric

dissection, the vulnerability of the radial neurovascular bundle concerning the metacarpal

head of the second toe is highlighted. The advantage of the dorsal approach is highlighted,

as it is simpler and has no risk of injuring vital structures, with the advantage

of being able to address any osteochondral fracture associated with the head of the

MTP. There was no apparent difference in stability after reduction by either approach.

They also emphasize that in all dissections, reduction necessarily required partial

or total release of the deep, transverse ligament, while sectioning of the superficial

and swimming transverse ligaments was only necessary for better exposure. The volar

approach allowed for anatomic restoration of the joint and access to volar plate repair;

this author did not find studies that evaluated its relationship with long-term instability.

Barry et al.17 recommend a volar approach for more experienced hand surgeons and a dorsal approach

for those starting surgery.

Pereira et al.22 reported a case of dislocation of the MCP of the index finger in which an open reduction

was performed via a lateral approach, finding the interposition of the volar plate

and an osteochondral fragment that blocked the reduction.

A straight longitudinal incision was made on the lateral aspect of the MCP joint;

the joint capsule was sectioned longitudinally above the collateral ligament, and

the volar neurovascular bundle and the dorsal nerve branches were identified and protected.

This approach gained access to the dorsal and volar structures, and the intervening

volar plate was reduced and reinserted with a 4.0 Vycril suture. An osteochondral

fragment was identified and fixed with a 1.7mm screw.

Regarding complications, one of the most encountered early is loss of joint amplitude,

which is more frequently manifested in lesions with a delayed surgical resolution,

severe joint infections associated with exposed dislocations, and damage to the digital

collateral nerve2. Among the late complications, osteoarthrosis of the joint and osteonecrosis have

been described, also associated with repeated failed attempts at closed reduction,

open dislocations and prolonged immobilization.

Postoperative immobilization is a controversial issue. Rubin et al.13, in their case series, performed immediately protected mobilization and used immobilization

in one patient for three days.

In their systematic review, Diaz Abele et al.1 suggest immobilization with a locked dorsal splint for two weeks followed by rehabilitation

by occupational therapy, which consists of passive and active range-of-motion exercises,

and complementary therapies to control edema and optimize the healing process23.

McLaughlin10, in his work, reports a less satisfactory range of motion in complex dislocations

immobilized for more than two weeks.

Durakbasa & Guneri2, on the other hand, performed immobilizations in their series of seven cases for

an average of three weeks, with a mean follow-up of 91 months, reporting excellent

functional results in all their patients, standing out as important data in the result

that five of them correspond to the pediatric age. Recovery with a normal range of

motion is generally expected within 6 weeks.

CONCLUSIONS

Complex dislocations of the metacarpophalangeal joint are rare lesions diagnosed by

clinical findings with a slightly hyperextended metacarpophalangeal joint, mild ulnar

deviation of the involved finger, volar palpation of the MCP head, and the presence

of dimples in the palmar skin.

Attempts at closed reduction of complex dislocations are often unsuccessful, and repeated

attempts often lead to additional complications. Open surgical reduction is the method

of choice for treating these injuries, allowing the joint anatomy to recover with

the lowest risk of complications.

Even after diagnosing complex dislocation, it is recommended to avoid closed maneuvers

and opt for open reduction as the first treatment option.

There are several approaches described. The volar approach allows direct access to

the lesion and anatomical restoration of the joint with the possibility of repairing

the volar plate, which may be related to a lower risk of late instability. The dorsal

approach also offers good exposure to the lesion, with a lower risk of injury to the

digital nerves, and also provides good access in cases that associate MCP osteochondral

fractures.

Immobilization with a dorsal locking splint for two weeks is recommended, followed

by rehabilitation and therapy to control edema and optimize the healing process.

As emergency physicians evaluate these patients, knowledge of this injury, proper

diagnosis and prompt referral to hand surgeons for surgical treatment are essential

and determine the functional prognosis of these injuries.

REFERENCES

1. Diaz Abele J, Thibaudeau S, Luc M. Open metacarpophalangeal dislocations: literature

review and case report. Hand (N Y). 2015;10(2):333-7. DOI: 10.1007/s11552-014-9646-6

2. Durakbasa O, Guneri B. The volar surgical approach in complex dorsal metacarpophalangeal

dislocations. Injury. 2009;40(6):657-9. DOI: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.10.027

3. Nussbaum R, Sadler AH. An isolated, closed, complex dislocation of the metacarpophalangeal

joint of the long finger: a unique case. J Hand Surg Am. 1986;11(4):558-61. DOI: 10.1016/S0363-5023(86)80198-8

4. Stiles BM, Drake DB, Gear AJ, Watkins FH, Edlich RF. Metacarpophalangeal joint dislocation:

indications for open surgical reduction. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(5):669-71.

5. Mudgal CS, Mudgal S. Volar open reduction of complex metacarpophalangeal dislocation

of the index finger: a pictorial essay. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2006;10(1):31-6.

DOI: 10.1097/00130911-200603000-00006

6. Wright CS. Compound dislocations of four metacarpophalangeal joints. J Hand Surg Br.

1985;10(2):233-5. DOI: 10.1016/0266-7681(85)90025-7

7. Kaplan EB. Dorsal dislocation of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the index finger.

J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1957;39-A(5):1081-6.

8. Green DP, Terry GC. Complex dislocation of the metacarpophalangeal joint. Correlative

pathological anatomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55(7):1480-6.

9. Imbriglia JE, Sciulli R. Open complex metacarpophalangeal joint dislocation. Two cases:

index finger and long finger. J Hand Surg Am. 1979;4(1):72-5. DOI: 10.1016/S0363-5023(79)80108-2

10. McLaughlin HL. Complex “locked” dislocation of the metacarpophalangeal joints. J Trauma.

1965;5(6):683-8.

11. Elghoul N, Bouya A, Jalal Y, Zaddoug O, Benchakroun M, Jaafar A. Complex metacarpophalangeal

joint dislocation of the litter finger: A sesamoid bone seen within joint. What does

it mean? Trauma Case Rep. 2019;23:100225. DOI: 10.1016/j.tcr.2019.100225

12. An MT, Kelley JP, Fahrenkopf MP, Kelpin JP, Adams NS, Do V. Complex Metacarpophalangeal

Dislocation. Eplasty. 2020;20:ic3.

13. Rubin G, Orbach H, Rinott M, Rozen N. Complex Dorsal Metacarpophalangeal Dislocation:

Long-Term Follow-Up. J Hand Surg Am. 2016;41(8):e229-33. DOI: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2016.05.010

14. Silberman WW. Clear view of the index sesamoid: a sign of irreducible metacarpophalangeal

joint dislocation. JACEP. 1979;8(9):371-3. DOI: 10.1016/S0361-1124(79)80262-2

15. Gerrand CH, Shearer H. Complex dislocation of the metacarpophalangeal joint of the

index finger with sesamoid entrapment. Injury. 1995;26(8):574-5. DOI: 10.1016/0020-1383(95)98148-C

16. Becton JL, Christian JD Jr, Goodwin HN, Jackson JG 3rd. A simplified technique for

treating the complex dislocation of the index metacarpophalangeal joint. J Bone Joint

Surg Am. 1975;57(5):698-700.

17. Barry K, McGee H, Curtin J. Complex dislocation of the metacarpo-phalangeal joint

of the index finger: a comparison of the surgical approaches. J Hand Surg Br. 1988;13(4):466-8.

DOI: 10.1016/0266-7681(88)90182-9

18. Lalonde DH, Martin A. Epinephrine in local anesthesia in finger and hand surgery:

the case for wide-awake anesthesia. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(8):443-7.

19. Bohart PG, Gelberman RH, Vandell RF, Salamon PB. Complex dislocations of the metacarpophalangeal

joint. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;(164):208-10.

20. Yadav SK, Nayak B, Mittal S. New approach to second metacarpophalangeal joint dislocation

management: the SKY needling technique. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2021;31(1):189-92.

DOI: 10.1007/s00590-020-02728-w

21. O’Neill ES, Qin MM, Chen KJ, Hansdorfer MA, Doscher ME. Dislocation of the metacarpophalangeal

joint of the index finger requiring open reduction due to the presence of an intra-articular

sesamoid bone. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2021;9:2050313X211021180. DOI: 10.1177/2050313X211021180

22. Pereira JM, Quesado M, Silva M, Carvalho JDD, Nogueira H, Alves J. The Lateral Approach

in the Surgical Treatment of a Complex Dorsal Metacarpophalangeal Joint Dislocation

of the Index Finger. Case Rep Orthop. 2019;2019:1063829. DOI: 10.1155/2019/1063829

23. Afifi AM, Medoro A, Salas C, Taha MR, Cheema T. A cadaver model that investigates

irreducible metacarpophalangeal joint dislocation. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(8):1506-11.

DOI: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.06.001

1. Hospital de Clínicas Dr. Manuel Quintela, Cátedra de Cirugía Plástica, Reparadora

y Estética, Montevidéu, Uruguai

Corresponding author: Victoria Hernández Sosa Mac Eachen, 1302, Montevidéu, Uruguai. Zip code: 11300, E-mail: victoria.hernandezsosa@gmail.com

Article received: October 22, 2021.

Article accepted: April 7, 2022.

Conflicts of interest: none.