INTRODUCTION

Treating complex wounds with great soft tissue loss is a challenge for plastic surgery,

especially when the wound is infected. In the literature, we find numerous already

established techniques, with their benefits and disadvantages, such as grafting, flaps,

tissue expanders and elastic suture.

The decision for the technique to be used is essential for successful reconstruction,

and, based on the principle that the best repair is always the simplest1, the fundamentals of reconstructive surgery were created. Therefore, primary wound

closure is the first choice whenever possible.

Raskin used an elastic suture for the first time in 1993 to approximate the borders

of a post-compartment syndrome fasciotomy in an upper limb2. The principle was based on the fixation with the tension of an interlaced elastic,

fixed to the edges of the skin, making a continuous tension of the skin, putting into

practice the concept of elasticity and skin compliance. It can be used to close different

skin defects resulting from different causes, such as car accidents, resections of

skin lesions and tissue necrosis. Elastic suture, as an alternative for treating the

acute phase of skin loss, is a simple, low-cost procedure that provides good results

for cases of tissue loss3.

In 1996, Leite revised the technique after observing the incidence of skin necrosis

at the edges of the wound, using the Raskin technique, and then proposed fixing the

elastic in the subcutaneous and superficial fascia, sparingly the skin from the ischemic

event induced by tensile force4.

The use of vacuum dressing, whose description in animal studies dates back to the

1970s5, has established itself as an important alternative in treating complex wounds, including

for the pediatric population6. It is a system used in wound healing in which localized and controlled negative

pressure is instituted to stimulate granulation and healing. Negative pressure promotes

arterial vasodilation and, consequently, increases blood flow in the tissues, stimulating

the formation of granulation scar tissue. Fluid removal decreases edema, interstitial

pressure, and bacterial colonization, creating a moist environment beneficial for

epithelial migration and healing. In addition, it produces traction on the wound’s

edges, reducing its dimension7.

Thus, this work aimed to combine the benefits of elastic suture and vacuum dressing

with a more comprehensive approach to a complex infected wound with great loss of

soft parts of the lower limb.

METHODS

This is a retrospective, observational study of a patient who underwent reconstruction

of the right lower limb using an elastic suture and a vacuum dressing at Hospital

do Trabalhador, in Curitiba-PR, in 2020. Study approved by the Ethics Committee on

Search under CAAE 52792121.7.0000.5225.

Patient DGLD, male, 20 years old, previously healthy, is referred to the Emergency

Department of the Hospital do Trabalhador in Curitiba, victim of a collision between

a motorcycle and a car. He is admitted to the emergency room with a significant laceration

on the right lower limb, extending from the knee to the distal third of the leg, with

no signs of fracture on radiography.

Upon admission, the patient underwent debridement and containment of the edges with

sterile plastic (Figure 1) by the orthopedics team, who requested a follow-up by the Plastic and Reconstructive

Surgery Service. On the seventh day of hospitalization, the patient underwent a new

surgical procedure by the plastic surgery team. A large clot was identified, exhaustive

washing was performed, and hemostasis was reviewed (Figure 2).

Figure 1 - Right lower limb with suture for edge containment with plastic equipment.

Figure 1 - Right lower limb with suture for edge containment with plastic equipment.

Figure 2 - Right lower limb after debridement of the lesion.

Figure 2 - Right lower limb after debridement of the lesion.

In the transoperative period, it was decided to perform the elastic suture associated

with the vacuum dressing (Figure 3), with a surgical reassessment plan and new reconstruction plan after 7 days, when

the rotation of the myocutaneous flap for closure was considered. In the surgical

reassessment, with satisfactory evolution of the wound, it was decided to maintain

the conduct of the elastic suture and vacuum therapy treatments.

Figure 3 - Production of an elastic suture in association with vacuum dressing in the right lower

limb injury.

Figure 3 - Production of an elastic suture in association with vacuum dressing in the right lower

limb injury.

The patient underwent two more approaches with an interval of 7 days, with this association,

with gradual wound closure (Figure 4) until the edges’ final primary suture and elastics’ removal (Figure 5). Patient, coming from another state, chose to end treatment in his hometown, without

new procedures. Photo, after contact with it, is in Figure 5.

Figure 4 - New confections of elastic sutures and vacuum dressing.

Figure 4 - New confections of elastic sutures and vacuum dressing.

Figure 5 - Final appearance after removal of elastic suture and primary suture of the lesion.

Figure 5 - Final appearance after removal of elastic suture and primary suture of the lesion.

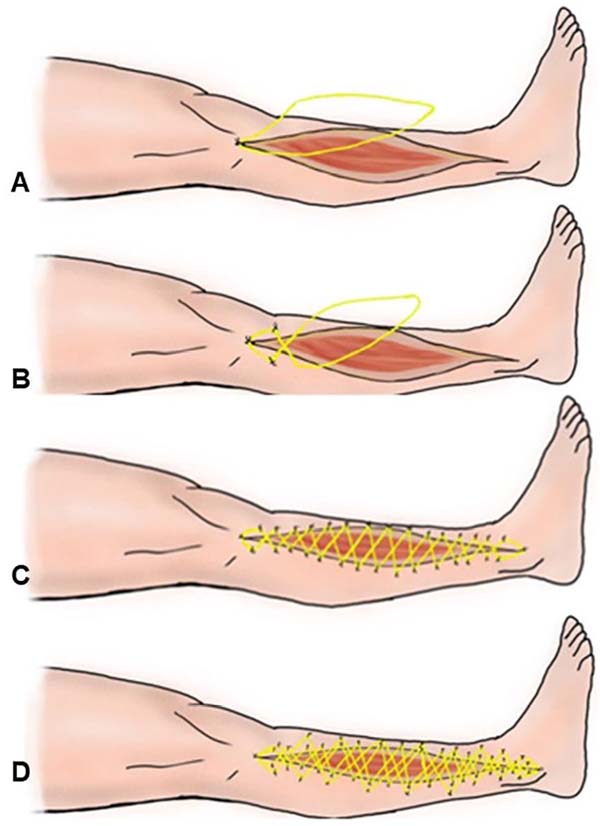

The demonstration of how the elastic suture is performed can be seen in Figure 6.

Figure 6 - Elastic suture. A) Starting point at the angle of the incision; B) 180º rotation of

the elastic and new sutures on the skin; C) Sequence of sutures until the end of the

incision; D) Suture distally to the wound with an elastic band to reduce tension on

the edges.

Figure 6 - Elastic suture. A) Starting point at the angle of the incision; B) 180º rotation of

the elastic and new sutures on the skin; C) Sequence of sutures until the end of the

incision; D) Suture distally to the wound with an elastic band to reduce tension on

the edges.

DISCUSSION

Complex wounds are the most challenging and often require a surgical approach. Wound

care aims to create a favorable environment for wound healing or coverage, and debridement

is the basis for most strategies. Primary synthesis, secondary synthesis, grafts,

local flaps, regional flaps, and free flaps are included from the simplest to the

most complex steps. When choosing the procedure, one should consider the best option

to maintain the shape and function of the region to be reconstructed8.

In the case in question, the elastic suture in association with the vacuum dressing

was effective in helping to definitively close the lesion, dispensing with the use

of skin autograft, flaps, or tissue expansion9. The open wound is maintained under elastic tension, which was exerted by sterile

rubber bands, performed by suturing the rubber with 2.0 and 3.0 nylon stitches attached

to the viable skin tissue. It starts with a stitch at the end of the wound and then

one on each side on the opposite skin edges after braiding the elastic at 180º, successively

repeating until the end of the incision.

During the treatment sequence, elastics sutured with Nylon 2-0 further away from the

edges were used to reduce the tension of the edges of the wound, thus avoiding cutaneous

vascular suffering, which was jointly benefited by the arterial vasodilation resulting

from the dressing to concomitant vacuum. During each procedure, sterile rubbers were

replaced with new ones to maintain effective tension and a new vacuum dressing.

After improving the tension of the wound by continuous traction and negative pressure,

it was possible to perform the primary suture of the lesion.

CONCLUSION

The use of continuous traction elastic suture associated with a vacuum dressing made

it possible to close a complex wound on the lower limb without the need for rotation

of the myocutaneous flap and other sequelae, proving to be an alternative with lower

morbidity for the case demonstrated.

REFERENCES

1. Mathes SJ, Nahai F. Reconstructive Surgery: Principles, Anatomy Techinique. New York:

Churchill Livingstone and Qualit Medical Publishing; 1997.

2. Raskin KB. Acute vascular injuries of the upper extremity. Hand Clin. 1993;9(1):115-30.

3. Vidal MA, Mendes Junior CES, Sanches JA. Sutura elástica - uma alternativa para grandes

perdas cutâneas. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;29(1):146-50.

4. Leite NM, Reis FB, Christian RW. Tratamento de ferimentos deixados abertos com o método

da sutura elástica. Rev Bras Ortoped. 1996;31:687-9.

5. Morykwas MJ, Argenta LC, Shelton-Brown EI, McGuirt W. Vacuum-assisted closure: a new

method for wound control and treatment: animal studies and basic foundation. Ann Plast

Surg. 1997;38(6):553-62.

6. Baharestani MM. Use of negative pressure wound therapy in the treatment of neonatal

and pediatric wounds: a retrospective examination of clinical outcomes. Ostomy Wound

Manage. 2007;53(6):75-85.

7. Oliveira MSL, Komatsu CA, Ching AW, Faiwichow L. Tratamento de feridas complexas com

uso de pressão negativa local método a vácuo. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2010;25(3 Suppl

1):66.

8. Petroianu A, Sabino KR, Alberti LR. Closure of large wound with rubber elastic circular

strips - case report. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2014;27(1):86-7. DOI: 10.1590/s0102-67202014000100021

9. Teixeira Neto N, Chi A, Paggiaro AO, Ferreira MC. Surgical treatment of complex wounds.

Rev Med (São Paulo). 2010;89(4/4):147-52.

1. Hospital de Clínicas de Curitiba, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

2. Hospital do Trabalhador, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

3. Universidade Federal do Paraná, Curitiba, PR, Brazil

4. Universidade de Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul, RS, Brazil

Corresponding author: Antoninho José Tonatto Filho Rua General Carneiro, 181, Setor/sala de Cirurgia Plástica, 9º andar, Alto da Glória,

Curitiba, PR, Brazil. Zip Code: 80060-900, E-mail: aj.tonatto@gmail.com

Article received: October 18, 2020.

Article accepted: September 13, 2022.

Conflicts of interest: none.