INTRODUCTION

By definition, burn is a tissue injury caused by any form of heat, contact with electric

current or chemical substance1, generating local, systemic, and metabolic effects, whose depth and extent depend

on the intensity and duration of the thermal agent2.

Burns are considered a global public health problem and have a higher incidence in

underdeveloped countries, accounting for approximately 180,000 deaths per year3. In Brazil, it is estimated that 1,000,000 accidents involving burns occur annually,

with 100,000 patients seeking medical assistance and of these, about 2,500 result

in death due to the severity of the injuries4.

In pediatric patients, burns are the second most common cause among incidents that

occur in childhood (mainly children under 14 years of age) and the third cause of

death in children5. Among the most frequent causal agents, scalding is consolidated as the main one,

followed by flammable liquid and heated surface2,6,7.

Among the risk factors linked to the development of this trauma, age of fewer than

5 years, male gender, domestic environment, superheated liquids and use of liquid

alcohol stand out8,9.

Burns can be classified according to extent and depth. As for the extent, several

methods are available to calculate this percentage10; a child with more than 10% of the affected body surface is considered a major burn7,11. Regarding depth, a 1st-degree burn affects only the epidermis, 2nd degree when it affects part of the dermis and 3rd degree when all layers of the skin and deep tissues are affected12. Short- and long-term morbidity and mortality are related to the extent and depth

of the lesions13,14, the initial approach and treatment instituted15, with infection as the main complication16,17. The psychosocial implications18,19 for the individual and the family should also be considered to minimize them.

The elaboration of care protocols20, the multidisciplinary approach21, and the structuring of specialized centers22 and intensive care units trained to accommodate this patient have contributed to

the reduction of mortality, reduction of functional, aesthetic and psychological sequelae,

improving the quality of life of these patients23.

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the most impactful public health issues in Brazil

and worldwide. The permanence of children and adolescents in the home environment

increases the risk of domestic accidents24, mostly unintentional and preventable situations.

The kitchen25,26 represents a great danger, as well as the frequent use of alcohol27, especially at this time for hand hygiene, surfaces and objects, highly flammable,

which makes it equally dangerous28, not to mention the use of cell phones and tablets while charging.

In this sense, the present study aims to analyze the rates of hospital admissions

due to burns in pediatric patients in the states of the Southern Region from 2016

to 2020, aiming to enrich the epidemiological knowledge about burns in Brazil and

possibly assist in prevention policies and burn patient care at local, state, regional,

and national levels.

OBJECTIVE

Main objective

To analyze the rates of hospital admissions due to burns in pediatric patients in

the states of the Southern Region (Paraná, Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul) from

2016 to 2020.

Specific objectives

Describe the socio-epidemiological characteristics of the victims;

Check the annual trend in the period studied;

Check the average length of stay of victims in hospitals;

Analyze the mortality rate of this trauma during the stipulated period;

To examine this trauma’s clinical outcome (death) in children and adolescents.

METHODS

This is a time series (ecological), descriptive and retrospective study of hospitalization

rates for burns in pediatric patients in the southern region of Brazil from 2016 to

2020. The study population following data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography

and Statistics (IBGE), comprising 8,256 children and adolescents aged 0 to 14 years

who had hospitalization registered in the Hospitalization Authorizations (HA) due

to burns and registered in the Hospital Information System (HIS/SUS) in the southern

region of the country, from 2016 to 2020. Incomplete data were excluded.

All patients, aged between 0 and 14 years, included in the HA from the South Region

of Brazil who were hospitalized and registered by the HIS/SUS for burns, which is

available at the Department of Informatics of the SUS (DATASUS), were included. Data

were stratified by gender and age group.

Data were obtained from DATASUS, the Hospital Information System (HIS), which were

grouped into the system through HA records. The data were accessed through the Tabwin

data tabulator and later converted into files compatible with the Excel program. For

the construction of the database, all hospitalizations for burns in the age group

from 0 to 14 years in the period from 2016 to 2020, according to the International

Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD-10), in the South Region were considered.

Data were organized in a database created and analyzed using Microsoft Excel® version

365 software. Quantitative variables were described using measures of central tendency

and data dispersion. Qualitative variables were described using absolute and percentage

frequency. The temporal trend was performed using linear regression. The statistical

significance level adopted was 5% (p<0.05).

The author stated that the data used in the preparation of the manuscript entitled

“Time series of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the southern region

of Brazil from 2016 to 2020” were obtained from the online database and access free

from HIS/SUS, available at DATASUS, which justifies the absence of the opinion of

the Research Ethics Committee (CEP). This information is available on the Internet

for a free consultation in the form of data aggregated by states and municipalities;

that is, they were not collected individually and nominally.

In this sense, there is no possibility of physical or moral damage from the individual’s

perspective and the collectivities, as the principles contained in Resolution 466

of December 12, 2012, were respected.

Thus, this article did not require submission to the CEP of the University of Southern

Santa Catarina (UNISUL).

RESULTS

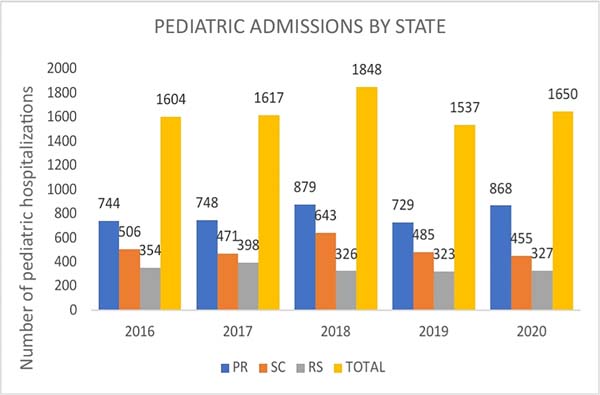

In the period from 2016 to 2020, 8,256 hospitalizations of children and adolescents

victims of burns were carried out in the Southern Region of Brazil, with the state

of Paraná as responsible for the highest rates throughout the period studied, as opposed

to the state of Rio Grande do Sul, with the minors. In 2018, the study showed its

worst data (n=1848) regarding the number of hospitalizations (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the Southern Region of Brazil

from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 1 - Hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the Southern Region of Brazil

from 2016 to 2020.

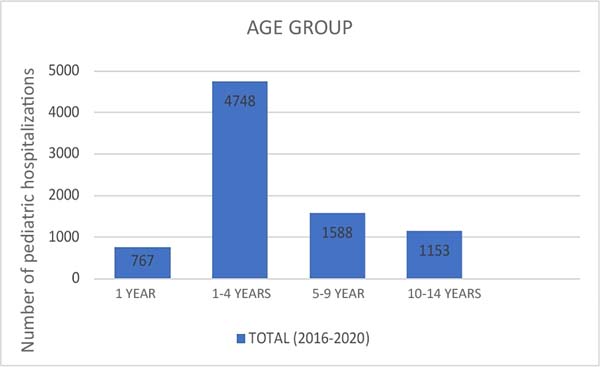

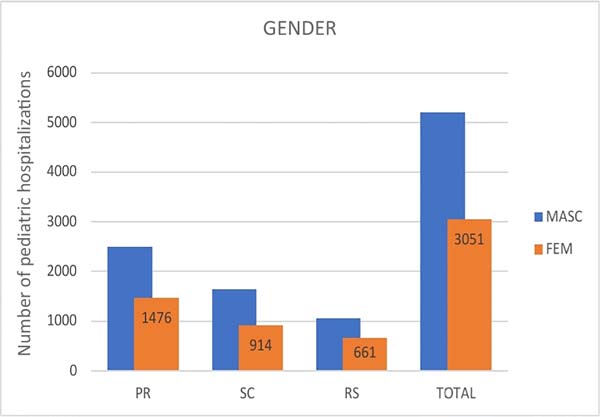

The main age group (Figure 2) involves preschool children aged 1-4 years (n=4748), followed by third childhood

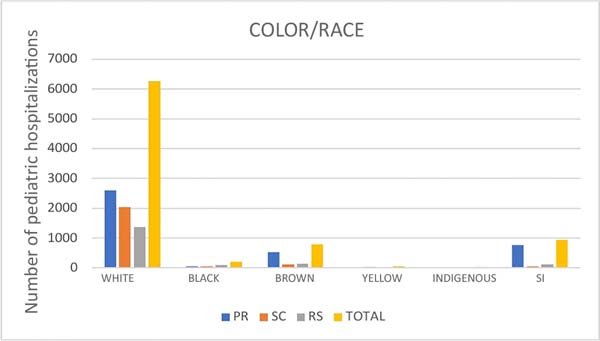

children aged 5-9 years (n=1588). As for gender (Figure 3), most of the children’s sample predominates males (n= 5205). Regarding color/race

(Figure 4), white color is predominant with 6263 of those involved, with medical records without

this variable (SI) obtaining numbers higher than black, brown, indigenous and yellow

in total (n=929), mainly in the state of Paraná (n=766).

Figure 2 - Age range of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the Southern Region

of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 2 - Age range of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the Southern Region

of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 3 - Gender of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the Southern Region

of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 3 - Gender of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the Southern Region

of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 4 - Color/race of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the Southern Region

of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 4 - Color/race of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the Southern Region

of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

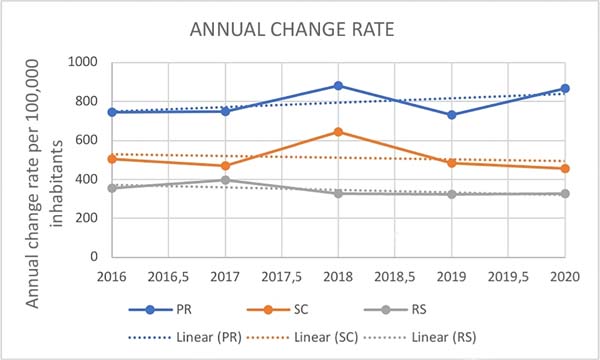

Regarding the annual trend, according to the Pearson scale (Table 1), it is noted that there was no significant linear correlation in the cases with

the occurrence of the years (Figure 5) of the studied period since the numbers presented are not close to or exceed the

value absolute of 1.

Table 1 - Correlation of annual variations in the Pearson Scale of hospital admissions for burns

in pediatric patients in the Southern Region of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

|

PR |

SC |

RS |

| R |

0.493 |

-0.184 |

-0.64 |

| P |

0.398 |

0.767 |

0.244 |

| N |

5 |

5 |

5 |

Table 1 - Correlation of annual variations in the Pearson Scale of hospital admissions for burns

in pediatric patients in the Southern Region of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 5 - Annual trend of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the Southern Region

of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 5 - Annual trend of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the Southern Region

of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

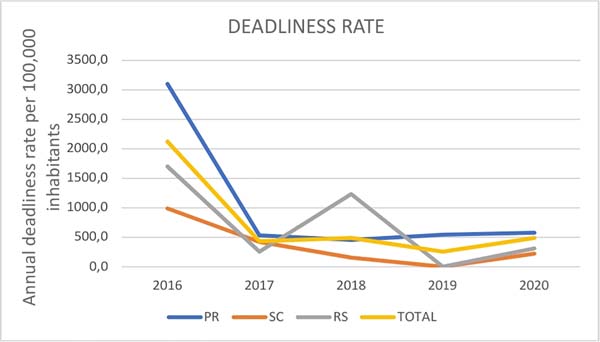

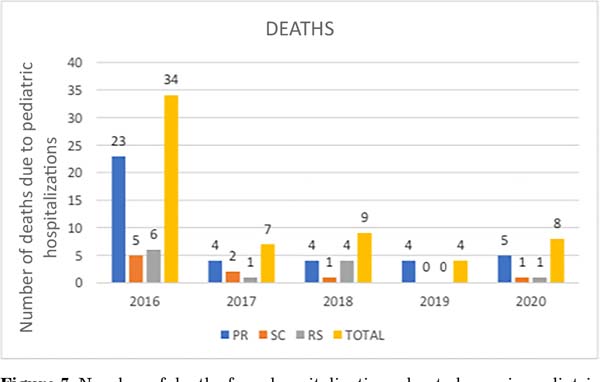

According to the lethality rate per 100,000 inhabitants (Figure 6) and the exact number of deaths (Figure 7), the state of Paraná leads in these variables, except for the year 2018, when the

state of Rio Grande surpasses it do Sul in fatality rate (n=1227.0), in almost all

the years evaluated, with the highest numbers obtained in 2016 - these being, respectively,

3091, 4 and 23. On the other hand, the lowest rates were obtained in 2019, with a

lethality rate of 0.0 for the states of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul due to

the non-occurrence of deaths in those states during this period.

Figure 6 - Lethality rate of hospital admissions due to burns in pediatric patients in the Southern

Region of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 6 - Lethality rate of hospital admissions due to burns in pediatric patients in the Southern

Region of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 7 - Number of deaths from hospitalizations due to burns in pediatric patients in the Southern

Region of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 7 - Number of deaths from hospitalizations due to burns in pediatric patients in the Southern

Region of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

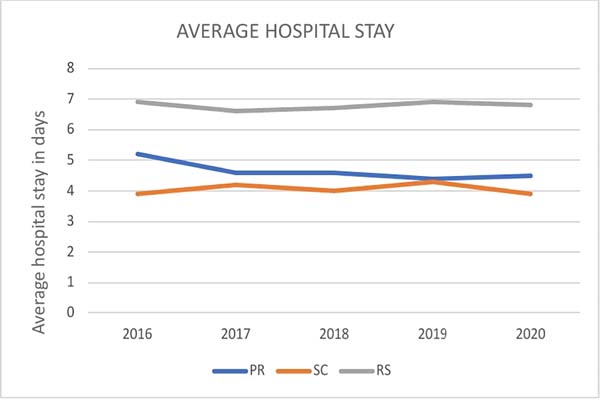

Analyzing the average length of hospital stay for pediatric burns in the South Region

of Brazil between 2016-2020 (Figure 8), Rio Grande do Sul has the highest average, reaching close to 7 days, especially

in 2016 and 2019. On the other hand, despite Paraná leading the hospitalization rate

throughout the period studied, it only figures with an average of more than 5 days

in 2016.

Figure 8 - Average length of stay of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the

Southern Region of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

Figure 8 - Average length of stay of hospitalizations for burns in pediatric patients in the

Southern Region of Brazil from 2016 to 2020.

DISCUSSION

Burns have been considered a serious public health problem in underdeveloped countries,

including Brazil. Knowledge of epidemiological data is of paramount importance to

provide subsidies for prevention and treatment programs, as well as helping to define

a parallel between the experiences of national and international centers11.

The data obtained in the present study demonstrated a stable temporal trend in the

number of pediatric burn hospitalizations in the southern region of Brazil during

the period studied (2016-2020). However, a similar study carried out throughout Brazil

between 2008 and 2015 showed increased cases in the South Region18. Likewise, when analyzing the hospitalization rate due to burns in each state, it

was found that Paraná had the highest rates concerning Santa Catarina and Rio Grande

do Sul for all age groups, in agreement with other authors15,29.

Regarding gender, there was a predominance of males, with 63.04% (n=5205) of cases,

a finding similar to that described by several authors2,5-8,11,15. This fact can be explained by the difference between the behavior of male and female

children, given that boys are educated to be more independent, have greater freedom

to carry out riskier activities and games, being more exposed to such accidents7.

Historically, burns are potentially preventable injuries, predominantly in the pediatric

class, requiring basic and essential care from their guardians and the children themselves6. This is demonstrated by the fact that 57.5% (n=4748) of burns occurred in children

aged 1-4 years, an age group in which, due to neuropsychomotor development, there

is no adequate notion of danger and safety. This data agrees with other published

studies, in which the average age of fewer than 5 years corresponds to most burn victims2,7,8,11,15. In this sense, it is necessary to increase vigilance on the part of parents and

other family members, in addition to the adoption of some preventive measures, such

as not leaving flammable liquids in the children’s field of vision, in an attempt

to reduce such rates in the appropriate age group.

In several publications2,6-8,11, it was demonstrated that superheated liquid was the main etiological agent of burns

in children in Brazil, surpassing liquid alcohol. This fact can be explained by an

article from 2009, as it shows a significant reduction of 10.16% in the incidence

of burns caused by liquid alcohol in children in the year immediately following the

ban on its sale30.

Analyzing the average hospitalization per state, it was noted that even the largest

of them, corresponding to Rio Grande do Sul, is in line with other literature, being

limited to a number lower than or close to two weeks2,7,11,22. However, another epidemiological study carried out between 2010 and 2017 in a hospital

in the southern region of Brazil found an average length of stay higher than those

described in this article6.

As for the outcome that occurred in this period, 0.76% (n=62) of the patients died,

a result that may be related both to better access to the specialized service and

notification by the states of this region18 and to governmental and non-governmental initiatives in the prevention of this stir

as the National Policy for Reducing Morbidity and Mortality from Accidents and Violence,

implemented in 2001 by the Ministry of Health, with proposals for specific actions

in all public spheres, whose guidelines aim to promote the adoption of safe and healthy

behaviors and environments31.

It is also worth noting, on a non-governmental level, the national burn prevention

campaigns developed by the Revista Brasileira de Queimaduras (RBQ) and the Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) Criança Segura, an affiliate of International Safe Kids Worldwide, based in Washington, D.C. in

the United States. Such idealizations are positive agents in the reduction of cases

of burns that require hospitalization since most occur accidentally18.

In general, all epidemiological studies are subject to bias. The data corresponding

to the three southern states shows a tendency towards stability in the number of pediatric

burn hospitalizations over the years. However, some limitations must be highlighted

in the interpretation. Including only hospitalization data from the DATASUS database

is prone to bias; that is, there may be underreporting of hospitalizations due to

external causes and some distortions concerning the types of causes in the HIS.

Added to this, another limitation refers to the funding source for these hospitalizations.

The present study only included hospitalizations financed by the SUS, which excludes

hospitalizations by private individuals and health insurance, which were not evidenced

in this study. As the vast majority of consultations are carried out via the SUS,

it is believed that the present work can offer a good picture of the reality of hospitalizations

due to burns in the southern region of Brazil.

CONCLUSION

In the period between 2016 and 2020, there were 8256 hospitalizations for burns in

children aged 0 to 14 years in the southern region of Brazil. Most of these (63.04%)

occurred in the male population and the age group of 1-4 years (57.5%). During the

studied period, there was no significant annual variation in the number of hospitalizations

for burns in Brazil when analyzing the age group of 0 - 14 years of each state in

the South Region. Separately, the state of Paraná had the highest rates of pediatric

hospitalization throughout the study. On the other hand, the state of Rio Grande do

Sul had the lowest rates.

Therefore, it is necessary to raise the awareness of parents and other family members

to increase vigilance and care for children and adolescents, seeking the adoption

of preventive measures against this tormentor. Furthermore, against burns, prevention

is the best treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Pereima MJL, Feijó R, Oenning da Gama F, de Oliveira Boccardi R. Treatment of burned

children using dermal regeneration template with or without negative pressure. Burns.

2019;45(5):1075-80.

2. Rigon AP, Gomes KK, Posser T, Franco JL, Knihs PR, Souza PA. Perfil epidemiológico

das crianças vítimas de queimadura em um hospital infantil da Serra Catarinense. Rev

Bras Queimaduras. 2019;18(2):107-12.

3. World Health Organization (WHO). Burns. Geneva: WHO; 2018. [acesso 2020 Set 21]. Disponível

em: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns

4. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Queimados; Brasília: Ministério da Saúde2017. [acesso

2020 Set 21]. Disponível em: https://www.saude.gov.br/component/content/article/842-queimados/40990-

5. Barcellos LG, Silva APPD, Piva JP, Rech L, Brondani TG. Characteristics and outcome

of burned children admitted to a pediatric intensive care unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva.

2018;30(3):333-7.

6. Nigro MVAS, Maschietto SM, Damin R, Costa CS, Lobo GLA. Perfil epidemiológico de crianças

de 0-18 anos vítimas de queimaduras atendidas no Serviço de Cirurgia Plástica e Queimados

de um Hospital Universitário no Sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2019;34(4):504-8.

7. Barros LAF, da-Silva SBM, Maruyama ABA, Gomes MD, Muller KTC, Amaral MAO. Estudo epidemiológico

de queimaduras em crianças atendidas em hospital terciário na cidade de Campo Grande/MS.

Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2019;18(2):71-7.

8. Meschial WC, Sales CCF, Oliveira MLF. Fatores de risco e medidas de prevenção das

queimaduras infantis: revisão integrativa da literatura. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2016;15(4):267-73.

9. Williams FN, Chrisco L, Nizamani R, King BT. COVID-19 related admissions to a regional

burn center: The impact of shelter-in-place mandate. Burns Open. 2020;4(4):158-9.

DOI: 10.1016/j.burnso.2020.07.004

10. Sinder R. Evolução histórica do tratamento das queimaduras. In: Guimarães Junior LM,

ed. Queimaduras. Rio de Janeiro: Rubio; 2006. p. 3-9.

11. Aragão JA, Aragão MECS, Filgueira DM, Teixeira RMP, Reis FP. Estudo epidemiológico

de crianças vítimas de queimaduras internadas na Unidade de Tratamento de Queimados

do Hospital de Urgência de Sergipe. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012;27(3):379-82.

12. Gattas AZ, Djaleta DG, Noviello DS, Thomaz MCA, Arçari DP. Atendimento do enfermeiro

ao paciente queimado. Saúde Foco. 2011;5(8):1-20.

13. Palmieri TL. Pediatric Burn Resuscitation. Crit Care Clin. 2016;32(4):547-59. DOI:

10.1016/j.ccc.2016.06.004

14. Shah AR, Liao LF. Pediatric Burn Care: Unique Considerations in Management. Clin Plast

Surg. 2017;44(3):603-10.

15. Yoda CN, Leonardi DF, Feijó R. Queimadura pediátrica: fatores associados a sequelas

físicas em crianças queimadas atendidas no Hospital Infantil Joana de Gusmão. Rev

Bras Queimaduras. 2013;12(2):112-7.

16. Oliveira FL, Serra MCVF. Infections in burns: a review. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2011;10(3):96-9.

17. Marques MD, Amaral V, Marcadenti A. Epidemiological profile of major burn inpatients

admitted in a trauma’s hospital. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2014;13(4):232-5.

18. Pereima MJL, Vendramin RR, Cicogna JR, Feijó R. Internações hospitalares por queimaduras

em pacientes pediátricos no Brasil: tendência temporal de 2008 a 2015. Rev Bras Queimaduras.

2019;18(2):113-9.

19. Siqueira FMB, Juliboni EPK. O papel da atividade terapêutica na reabilitação do indivíduo

queimado em fase aguda. Cad Ter Ocup UFSCar. 2000;8(2):79-81.

20. Henrique DM, Silva LD, Costa ACR, Rezende APMB, Santos JAS, Menezes MM, et al. Controle

de infecção no centro de tratamento de queimados: revisão de literatura. Rev Bras

Queimaduras. 2013;12(4):230-4.

21. Farina Junior JA. O papel da equipe multidisciplinar na prevenção de infecção no grande

queimado. Revi Bras Queimaduras. 2015;14(3):191-2.

22. Takino MA, Valenciano PJ, Itakussu EY, Kakitsuka EE, Hoshimo AA, Trelha CS, et al.

Perfil epidemiológico de crianças e adolescentes vítimas de queimaduras admitidos

em centro de tratamento de queimados. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2016;15(2):74-9.

23. Silva AFR, Oliveira LP, Vale MB, Batista KNM. Análise da qualidade de vida de pacientes

queimados submetidos ao tratamento fisioterapêutico internados no Centro de Tratamento

de Queimados. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2013;12(4):260-4.

24. Rede Nacional da Primeira Infância. Mapeamento da ação finalística - Evitando acidentes

na primeira infância. 2014. Disponível em: http://primeirainfancia.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/RELATORIO-DE-MAPEAMENTO-EVITANDO-ACIDENTES-versao-4--solteiras.pdf

25. Blank D. Segurança no Ambiente Doméstico. In: Sociedade Brasileira de Pediatria. Tratado

de Pediatria. 4ª. ed. Barueri: Editora Manole; 2017. p. 71-4.

26. Brasil. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária (ANVISA). Nota Técnica Gvims/Ggtes/Anvisa

Nº 04/2020. Orientações para serviços de saúde: medidas de prevenção e controle que

devem ser adotadas durante a assistência aos casos suspeitos ou confirmados de infecção

pelo novo coronavírus (SARS-CoV- 2). [acesso 2020 Set 23]. Disponível em: http://portal.anvisa.gov.br/documents/33852/271858/Nota+T%C3%A9cnica+n+04-2020+GVIMS-GGTES-ANVISA/ab598660-3de4-4f14-8e6fb9341c196b28

27. Secretaria de Estado da Sáude do Governo de Goiás. Hugol alerta sobre perigos de queimaduras

durante a quarentena. [acesso 2020 Abr 4]. Disponível em: https://www.agirsaude.org.br/noticia/view/652/hugol-alerta-sobre-os-perigos-de-queimaduras-no-periodo-de-quarentena

28. Silva CVF, Besborodco RM, Rodrigues CL, Górios C. Isolamento social devido à COVID-19

- epidemiologia dos acidentes na infância e adolescência. Resid Pediatr. 2020;10(3):1-6.

29. Favassa MT, Vietta GG, Nazário NO. Tendência temporal de internação por queimadura

no Sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2017;16(3):163-8.

30. Pereima MJL, Mignoni ISP, Bernz LM, Schweitzer CM, Souza JA, Araújo EJ, et al. Análise

da incidência e da gravidade de queimaduras por álcool em crianças no período de 2001

a 2006: impacto da Resolução 46. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2009;8(2):51-9.

1. Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina, Curso de Medicina, Tubarão, Santa Catarina,

Brazil

Corresponding author: Thiago Gonçalves Souza Rua vigário José Poggel, 588, ed Torre di Fiori, ap 204, Tubarão, SC, Brazil. Zip

code: 88704-240, E-mail: thiago_goncalves_220@hotmail.com

Article received: September 19, 2021.

Article accepted: December 13, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.