INTRODUCTION

Fournier’s gangrene (Figure 1) is a term that was first described in 1883 by Alfred Fournier to designate necrotizing

fasciitis that affects the scrotum and perineum. It has a polybacterial etiology,

usually caused by anaerobic and aerobic bacteria1. It is an infection of rapid progression, with a high potential for severity (high

rates of morbidity and mortality), being more common in males2. Its risk factors are diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, obesity, local trauma, perianal

and perineal infections, and surgical procedures in the region1. The treatment is based on surgical intervention with early excision of the necrotic

area and antibiotic therapy, which may require reapproaches with the expansion of

the debrided area2.

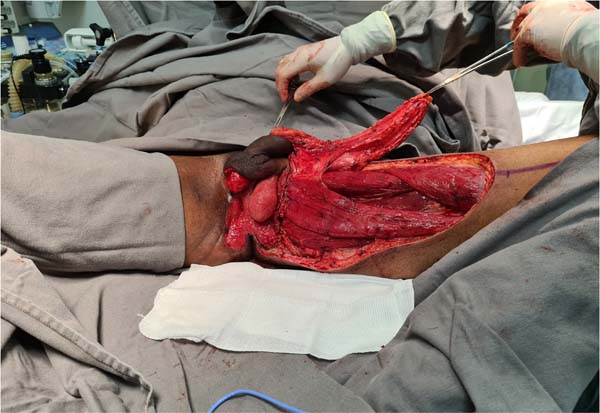

Figure 1 - Aspect of a scrotum affected by Fournier’s gangrene. Areas of induration, hyperemia,

and wound drainage with fetid purulent secretion are common.

Figure 1 - Aspect of a scrotum affected by Fournier’s gangrene. Areas of induration, hyperemia,

and wound drainage with fetid purulent secretion are common.

There are several strategies for reconstructing the bloody area resulting from debridement.

Small wounds with tissue loss of up to 50% of the scrotum can generally be treated

with secondary intention healing, primary synthesis and skin grafting. Larger losses

are usually treated using skin, fasciocutaneous or myocutaneous flaps2.

In this article, the authors’ reconstructive strategies after the debridement of eight

patients with Fournier’s gangrene will be analyzed, with the fasciocutaneous thigh

flap as the first option.

OBJECTIVE

To evaluate the outcome of scrotal reconstructions performed by the authors after

debridement of Fournier’s gangrene and whether there are any complicating factors

such as comorbidities and/or alteration of laboratory tests.

METHODS

The authors performed a retrospective analysis of the series of cases of scrotal reconstruction

after Fournier’s gangrene throughout 2020 (Table 1). In all cases, one or both testicles were exposed. Medical records, photo files,

albumin, and complete blood count tests were accessed immediately before the reconstructive

surgical stage.

Table 1 - Table with the data of each patient reconstructed after debridement of Fournier’s

gangrene, including age, preoperative exams, comorbidities, the operative technique

used, its complications and if any revision or secondary procedure was necessary.

| Patient |

Age |

GL |

Hb |

CRP |

Comorbidities |

Technique |

Complications |

Revision |

| W.R.G. |

46 |

10100 |

9.3 |

129.82 |

SAH |

Bilateral fasciocutaneous thigh flaps |

Dehiscence |

Two z-plasties, resection of excess skin |

| S.H.M.F. |

47 |

2786 |

7.46 |

35.8 |

DM |

Unilateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap |

No complications |

None |

| G.M.A. |

60 |

11540 |

10.65 |

42.5 |

SAH, DM, CAD |

Gracilis myocutaneous flap |

Partial skin island necrosis |

Debridement |

| R.A.P. |

46 |

4312 |

10.03 |

2.6 |

Alcoholism |

Unilateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap |

Epidermolysis |

None |

| R.L.A. |

74 |

12800 |

9.28 |

149.8 |

SAH, MD |

Primary closure |

Dehiscence |

None |

| J.B.L. |

48 |

6100 |

10.6 |

122 |

DM |

Unilateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap |

Partial necrosis |

Debridement and edge reapproximation |

| A.F.S |

51 |

6940 |

9.8 |

30.7 |

SAH, MD |

Unilateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap thigh |

Epidermolysis |

Debridement and edge reapproximation |

| R.D.G.F. |

48 |

6140 |

11.9 |

6.3 |

SAH, DM, asthma |

Unilateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap |

Dehiscence |

None |

Table 1 - Table with the data of each patient reconstructed after debridement of Fournier’s

gangrene, including age, preoperative exams, comorbidities, the operative technique

used, its complications and if any revision or secondary procedure was necessary.

The total number of patients was eight, and the primary surgical option was the fasciocutaneous

thigh flap, which was used on six occasions. The two exceptions were due to a urethral

injury or inadequate clinical conditions for a larger reconstruction.

RESULTS

The authors’ first option for making the neoscrotum after debridement of Fournier’s

gangrene was the unilateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap (Figures 2 to 5). Using two flaps from both thighs was reserved for a patient with a more extensive

open wound (Figures 6 to 10). There was no case of total necrosis. One of the seven flaps performed evolved

with partial necrosis, which is equivalent to a rate of vascular damage of 14.29%.

Figure 2 - Unilateral fasciocutaneous thigh flap.

Figure 2 - Unilateral fasciocutaneous thigh flap.

Figure 3 - Marking of a unilateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap. Note that this patient’s thigh

has a reduced circumference.

Figure 3 - Marking of a unilateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap. Note that this patient’s thigh

has a reduced circumference.

Figure 4 - Photo showing the superomedial pedicle of the flap marked in

Figure 3. It is possible to identify the following muscles in the dissection (from posterior

to anterior region): adductor magnus, gracilis, vastus medialis, adductor longus and

sartorius.

Figure 4 - Photo showing the superomedial pedicle of the flap marked in

Figure 3. It is possible to identify the following muscles in the dissection (from posterior

to anterior region): adductor magnus, gracilis, vastus medialis, adductor longus and

sartorius.

Figure 5 - Due to the reduced thickness of this patient’s thigh, as seen in

Figure 4, it was decided to perform skin grafting on the thigh to reduce tension during closure.

The donor area was the skin already removed from the scrotum in the same surgical

procedure.

Figure 5 - Due to the reduced thickness of this patient’s thigh, as seen in

Figure 4, it was decided to perform skin grafting on the thigh to reduce tension during closure.

The donor area was the skin already removed from the scrotum in the same surgical

procedure.

Figure 6 - Marking fasciocutaneous thigh flaps to cover an extensive scrotal wound after debridement

of Fournier’s gangrene.

Figure 6 - Marking fasciocutaneous thigh flaps to cover an extensive scrotal wound after debridement

of Fournier’s gangrene.

Figure 7 - Dissection of fasciocutaneous thigh flaps whose markings are shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 7 - Dissection of fasciocutaneous thigh flaps whose markings are shown in

Figure 6.

Figure 8 - Transposition of the distal regions of the flaps shown in

Figures 6 and

7 to the perineum. When bilateral fasciocutaneous flaps are used, they are sutured

in the midline, mimicking the scrotal raphe.

Figure 8 - Transposition of the distal regions of the flaps shown in

Figures 6 and

7 to the perineum. When bilateral fasciocutaneous flaps are used, they are sutured

in the midline, mimicking the scrotal raphe.

Figure 9 - Immediate postoperative appearance of the perineal region after scrotal reconstruction

with fasciocutaneous flaps from the thighs, whose surgical steps are shown in

Figures 6,

7 and

8. Note that partial skin grafting was also performed on the penis.

Figure 9 - Immediate postoperative appearance of the perineal region after scrotal reconstruction

with fasciocutaneous flaps from the thighs, whose surgical steps are shown in

Figures 6,

7 and

8. Note that partial skin grafting was also performed on the penis.

Figure 10 - Aspect of the perineal region of the patient in

Figures 6,

7,

8 and

9 one year after its reconstruction. With little more than six months, a small intervention

was performed for resectioning excess skin near the glans and two zetaplasties at

the base of the penis to improve aesthetics.

Figure 10 - Aspect of the perineal region of the patient in

Figures 6,

7,

8 and

9 one year after its reconstruction. With little more than six months, a small intervention

was performed for resectioning excess skin near the glans and two zetaplasties at

the base of the penis to improve aesthetics.

Another flap used in the series was the gracilis myocutaneous flap due to a urethral

injury (Figures 11 to 14). There was an evolution to partial suffering of the island of skin, but the

muscle tissue remained viable, making it possible to remove the urethral indwelling

bladder probe and obtain a good urinary stream.

Figure 11 - Patient with a large anterior urethral defect after debridement of Fournier’s gangrene.

Programmed reconstruction of the urethral and bloody scrotal area in conjunction with

Urology, and it was possible to observe the marking of the gracilis myocutaneous flap

on the left thigh.

Figure 11 - Patient with a large anterior urethral defect after debridement of Fournier’s gangrene.

Programmed reconstruction of the urethral and bloody scrotal area in conjunction with

Urology, and it was possible to observe the marking of the gracilis myocutaneous flap

on the left thigh.

Figure 12 - Closure of the spongy urethra defect with jugal mucosa graft on the posterior wall,

lateral relaxation incisions and anterior primary synthesis. The Urology team performed

this surgical step.

Figure 12 - Closure of the spongy urethra defect with jugal mucosa graft on the posterior wall,

lateral relaxation incisions and anterior primary synthesis. The Urology team performed

this surgical step.

Figure 13 - Photo showing the dominant pedicle of the gracilis muscle, originating from a branch

of the deep femoral artery. Note that the muscle is already covering the reconstructed

urethra to increase blood supply and decrease the chance of urinary fistula.

Figure 13 - Photo showing the dominant pedicle of the gracilis muscle, originating from a branch

of the deep femoral artery. Note that the muscle is already covering the reconstructed

urethra to increase blood supply and decrease the chance of urinary fistula.

Figure 14 - Immediate postoperative appearance of the perineal region after reconstruction with

a gracilis myocutaneous flap. This patient evolved with partial necrosis of the skin

island and underwent sequential debridement. After the indwelling urinary catheter

was removed, there was spontaneous diuresis, with no evidence of urinary fistula one

year after surgery.

Figure 14 - Immediate postoperative appearance of the perineal region after reconstruction with

a gracilis myocutaneous flap. This patient evolved with partial necrosis of the skin

island and underwent sequential debridement. After the indwelling urinary catheter

was removed, there was spontaneous diuresis, with no evidence of urinary fistula one

year after surgery.

And in one of the patients, we opted for the primary synthesis of the wound edges

post-Fournier because he was elderly, hypertensive, diabetic, malnourished and with

significant anemia, which made reconstruction using flaps unfeasible.

In addition to the two already mentioned partial necroses, five cases had minor complications:

three dehiscences and two epidermolysis. As a result, four of the eight patients underwent

simple revision procedures: three debridements, two of which also had the edges reapproximated,

and one improvement in the aesthetic appearance through resection of excess skin and

two zetaplasties.

It should be noted that the average time between the initial debridement and the reconstructive

stage was 29 days. The average age of the eight patients was 52 years and six months.

As for comorbidities, the most frequent were diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension,

with respective prevalences of 75% and 62.50%. Asthma, coronary artery disease and

alcoholism were also reported in 1/8 of the cases, which corresponds to a prevalence

of 12.50% for each of these disorders. Regarding the preoperative revisions of the

reconstructions, the averages of global leukocytes, hemoglobin and C-reactive protein

were, respectively: 7590 leukocytes/microL, 9.88g/dL and 64.94mg/L.

DISCUSSION

The fasciocutaneous flap of the thigh was our main reconstructive choice because it

has a reliable vascular supply with a good range of rotation, thin skin, does not

leave exposed scars, is easy to perform technically, and because it preserves the

musculature. On the other hand, color incompatibility, low skin sensitivity1, and possibly inadequate thickness have been described in very obese patients.

The initial step in its marking is to draw a line from the pubic tubercle to the medial

condyle of the tibia, which is the insertion site of the “pars anserina.” The vascular

pedicle is then preserved in the superomedial region, and the flap length is determined

according to the amount of tissue required to perform the transposition.

In most cases, using only one flap was preferred because the scrotal defects were

smaller and to shorten the surgical time. The disadvantages of the unilateral flap

are mentioned: the lack of mimicry of the median raphe and the greater chance of the

tip suffering with the increase in the length X width ratio. Two of the five cases

of unilateral thigh fasciocutaneous flap presented distal epidermolysis, while one

evolved with partial necrosis. Probably something that contributed to this necrosis

was the patient’s disrespect for postoperative rest.

A possible technical refinement of the thigh fasciocutaneous flap is using only one

perforator of the medial circumflex femoral artery1,2. Other flaps that repair a scrotal defect are superficial circumflex iliac artery

perforator flap3, free or pedicled greater omentum flap4,5, bilateral gracilis muscle flap6,7, anterolateral thigh flap8, inguinal flap (McGregor’s)9 and associated flaps to the use of expander10.

The main disadvantages of some of these techniques, which prevented them from being

our choices, are high morbidity from laparotomy or laparoscopy and the possibility

of inguinal hernia with the use of a great omentum flap, need for a skin graft for

the omentum techniques and the bilateral gracilis muscle flap; possibility of tissue

expander extrusion when it is positioned close to a contaminated wound.

Rarely, there is urethral involvement due to Fournier’s gangrene, given that the vascular

supply of the urethra is different compared to the skin, subcutaneous tissue and fascia1. As muscle flaps increase oxygen tension and, consequently, reduce the chance of

urinary fistulization, we preferred the gracilis myocutaneous flap in cases in which

urethral reconstruction was necessary. This muscle is Mathes and Nahai type II, with

the main vascular contribution being the medial femoral circumflex artery, which is

located approximately 6-10 cm from the pubic tubercle1.

A jugal mucosal graft was also used on the posterior wall of the injured spongy urethra.

The skin island of the myocutaneous flap was used to close the scrotal wound but evolved

with partial necrosis and subsequent need for debridement. Perhaps an option with

less probability of intercurrences would be the gracilis muscle flap associated with

a partial skin graft instead of the gracilis myocutaneous flap. The balance was extremely

positive since the chances of a definitive urethrostomy were not small.

In the case we primarily repaired the scrotal wound, the initial choice was early

dehospitalization and postponement of reconstruction in better clinical conditions.

However, the patient’s social context did not allow this strategy. This highlights

the difficulty and complexity of managing surgical reconstructions in public health,

where a vulnerable population is more frequent than in private services. We believe

that this is a determining factor for surgical outcomes.

Other factors that may have had an unfavorable impact on the patients’ evolution are

1) High prevalence of comorbidities, especially diabetes mellitus; 2) Maintenance

of an inflammatory state at the time of reconstruction, as evidenced by the C-reactive

protein value; 3) Presence of anemia.

It is noteworthy that, concerning simpler reconstructive options, healing by secondary

intention takes time and results in a poor aesthetic appearance6; while skin grafting promotes a desirable thin coverage, its fixation in the perineal

region is difficult. In addition, the graft can adhere to the testicles and cause

contractures that hinder the cremasteric reflex necessary for the testicles not to

be affected by external conditions10. So, although there is no consensus on the best surgical option, flaps accelerate

the healing process and maintain the aspect of the scrotum necessary for thermoregulation

of the testicle2.

CONCLUSION

Scrotal reconstruction with flaps is important to accelerate wound healing from Fournier’s

gangrene debridement and to maintain the pouch appearance necessary for testicular

thermoregulation. Our primary option was the thigh fasciocutaneous flap, which proved

safe, with a partial necrosis rate of 14.29% and without total necrosis. It was also

possible to reconstruct a spongy urethra with gracilis muscle without fistulization,

preventing the patient from undergoing a definitive urethrostomy. As for complications,

the occurrence of minor intercurrences that require simple revision procedures is

common. This may result from important associated comorbidities and patients’ clinical

conditions during reconstructive plastic surgery.

REFERENCES

1. Coskunfirat OK, Uslu A, Cinpolat A, Bektas G. Superiority of medial circumflex femoral

artery perforator flap in scrotal reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;67(5):526-30.

2. Mello DF, Helene Júnior A. Scrotal reconstruction with superomedial fasciocutaneous

thigh flap. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2018;45(1):e1389.

3. Han HH, Lee JH, Kim SM, Jun YJ, Kim YJ. Scrotal reconstruction using a superficial

circumflex iliac artery perforator flap following Fournier’s gangrene. Int Wound J.

2016;13(5):996-9.

4. Delgado R, Ciudad P, Espinoza FB, Lopez J. Minimal invasive laparoscopic harvest of

the greater omental flap for Fournier’s gangrene scrotal reconstruction. J Plast Reconstr

Aesthet Surg. 2019;72(2):335-54.

5. Ng D, Tang CB, Kadirkamanathan SS, Tare M. Scrotal reconstruction with a free greater

omental flap: A case report. Microsurgery. 2010;30(5):410-3.

6. Katusabe LJ, Balumuka D, Hodges A. Scrotal reconstruction with a pedicled gracilis

muscle flap after debridement of Fournier’s gangrene: a case report. East Afr Med

J. 2013;90(11):375-8.

7. Banks DW, O’Brien 3rd DP, Amerson JR, Hester Jr TR. Gracilis musculocutaneous flap

scrotal reconstruction after Fournier gangrene. Urology. 1986;28(4):275-6.

8. Yu P, Sanger JR, Matloub HS, Gosain A, Larson D. Anterolateral thigh fasciocutaneous

flap island flaps in perineoscrotal reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109(2):610-6.

Discussion 617-8.

9. Ghahestani SM, Hekmati P, Karimi S. A new technique of scrotoplasty following total

scrotal destruction by raised rotated perineal flaps with de epithelialized borders.

Urol J. 2019;16(2):221-3.

10. Atik B, Tan O, Ceylan K, Etlik O, Demir C. Reconstruction of wide scrotal defect using

superthin groin flap. Urology. 2006;68(2):419-22.

1. Hospital Metropolitano Odilon Behrens, Cirurgia Plástica, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

2. Hospital Metropolitano Odilon Behrens, Cirurgia Geral, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

3. Hospital Metropolitano Odilon Behrens, Urologia, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

Corresponding author: Leandro Ricardo de Aquino Santos Av. Professor Alfredo Balena, 189, 10º andar, Santa Efigênia, Belo Horizonte, MG,

Brazil. Zip code: 30130-103, E-mail: leandroras@yahoo.com.br

Article received: November 25, 2021.

Article accepted: July 11, 2022.

Conflicts of interest: none.