INTRODUCTION

Skin cancer is the neoplasm with the highest incidence both in Brazil and in the world1. Much attention is directed to melanomas, but non-melanomas such as basal cell carcinoma

(BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) also profoundly impact public health.

The main risk factor for the onset of skin cancer, in general, is exposure to solar

ultraviolet radiation2. Some studies have documented a strong relationship between BCC and melanoma with

intermittent intense sun exposure, especially before 20 years of age, while SCC occurs

due to the cumulative effect of ultraviolet radiation throughout life, appearing in

photodamaged areas3. Other risk factors have also been identified for skin cancer, such as red hair,

clear eyes and skin, dysplastic nevi, smoking, alcohol consumption, arsenic exposure,

ionizing radiation, chronic skin irritation processes, burn scars, use of immunosuppressants

and papillomavirus infection. Genetic alterations may also predispose to early-manifestation

skin cancer, as in the case of xeroderma pigmentosum and basocellular nevus syndrome4,5.

The most common skin cancer is BCC, accounting for approximately 80% of diagnosed

cases. SCC is the second most common, and its incidence is increasing progressively.

Malignant melanoma accounts for only about 5% of skin cancers worldwide but is responsible

for more than 77% of cancer-related deaths.

Often skin neoplasms, when they are diagnosed, show no symptoms. In most cases, the

primary lesion is perceived by the patient or some family member6. Even if it is not a specialist physician who is the first to evaluate this lesion,

a well-trained eye may have good accuracy to differentiate benign lesions from malignant

lesions( 7).

The head and neck are sites very susceptible to skin neoplasms development because

they are generally more exposed to the sun. However, in these regions, the lesions

may be barely visible by the person himself or hidden in the hair, causing a delay

in his diagnosis and treatment, contributing to the prognosis’s worsening.

Hairdressers and beauty professionals are professionals still little explored in their

potential for early detection of these lesions8. Skin neoplasms, especially melanomas, can be easily screened through well-established

criteria9.

Considering these factors and the current reality, where knowledge is available on

an ever-increasing scale through digital platforms, the “Projeto Pele Alerta” (PPA) (Alert Skin Project) was conceived to bring accurate information to professionals

who work directly with the beauty and personal care market.

METHODS

The research ethics committee approved this project of UNIFESP with the number 3415290116/2016.

It was defended as a thesis in the professional master’s degree in science, technology,

and management applied to tissue regeneration.

Firstly, the target audience was defined, consisting of all beauty or related professionals

who work in direct contact with the population’s skin, such as hairdressers, manicurists,

tattoo artists, makeup artists, massage therapists, among others.

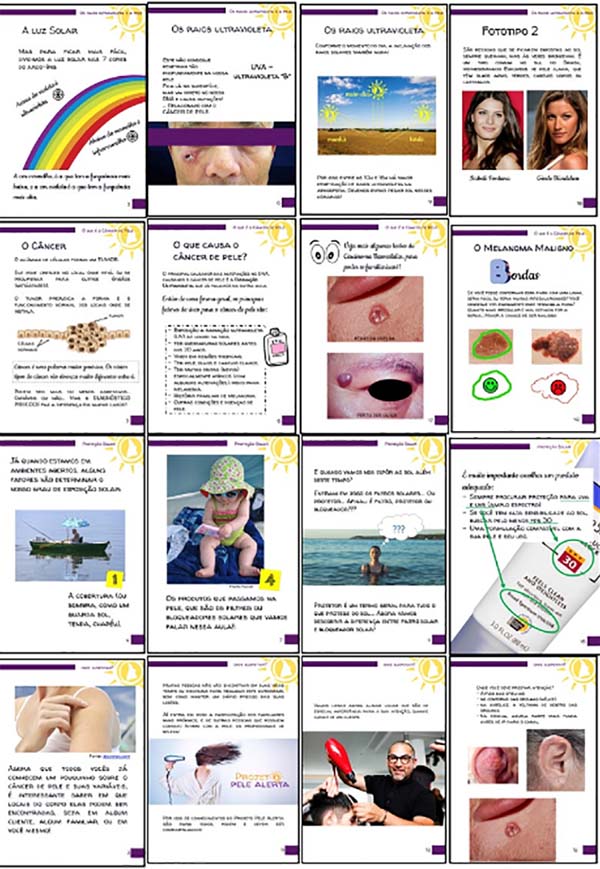

A completely online and free project was developed, in which these professionals can

have access to educational videos, accompanied by material illustrated in PDF format

on the project’s website (www.projetopelealerta.com).

The name “Project Alert Skin” was defined in a way to directly present its purpose:

to create an alert in these professionals, so that, knowing what skin cancer is, its

possible presentations and causes, they can detect suspicious lesions and refer to

medical care.

RESULTS

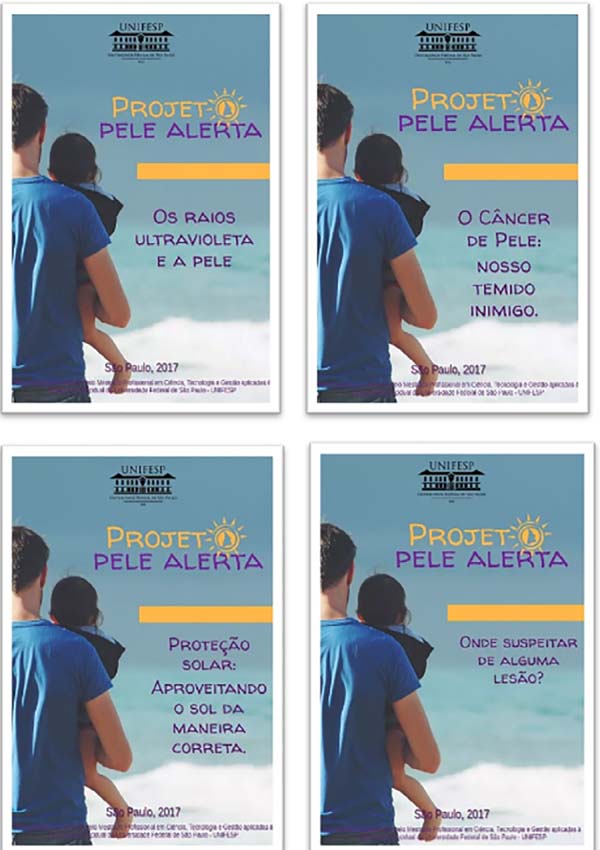

The initial program of the “Projeto Pele Alerta” has four chapters, with possible

future expansions:

Ultraviolet ray and skin. Nodes about ultraviolet rays and how they affect the skin;

Skin cancer: our feared enemy. Brings the types of skin cancer with some features

and photos to illustrate;

Sun protection: enjoying the sun in the right way. Views on photoprotection and prevention

of skin cancer.

Where to suspect any injury? Tips to professionals who watch the content about where

to pay special attention during their daily work.

The website of “Projeto Pele Alerta” (www.projetopelealerta.com) centralizes the campaign’s

subject and serves as a starting point for professionals who wish to access its contents.

The site’s slogan, “Beauty allied to prevention,” aims to make the professional who

works with beauty feel familiar with the content. It also carries the message: “Take

care of your clients in an even more special way” because knowledge adds value to

their everyday work, with a role in the prevention and early detection of skin cancer

(Figure 1).

Figure 1 - “Home” page of the “Projeto Pele Alerta”.

Figure 1 - “Home” page of the “Projeto Pele Alerta”.

In the “Downloads” section, participants have access to the list of topics covered

and a link to download the support material in PDF (Figures 2, 3 and 4).

Figure 2 - “Downloads” page of the “ Projeto Pele Alerta “.

Figure 2 - “Downloads” page of the “ Projeto Pele Alerta “.

Figure 3 - Covers of PDF files.

Figure 3 - Covers of PDF files.

Figure 4 - Mosaic with pages of material in PDF.

Figure 4 - Mosaic with pages of material in PDF.

In the “Videos” section, there is a thumbnail for each video of the “Projeto Pele

Alerta.” Participants can choose to watch them from their website or migrate to YouTube

and watch there (Figures 5 and 6).

Figure 5 - “Videos” page of the “ Projeto Pele Alerta “.

Figure 5 - “Videos” page of the “ Projeto Pele Alerta “.

Figure 6 - Print video of the “Projeto Pele Alerta”.

Figure 6 - Print video of the “Projeto Pele Alerta”.

In the “Contact” section, there is a possibility of contact with the project organizers,

creating a bilateral communication that allows feedback, in addition to the possible

comments on the videos.

DISCUSSION

The current panorama of Brazil, increasingly online, mainly due to the broad access

to the internet and smartphones, fosters a range not previously possible for preventive

campaigns. An online project manages to reach many wilderness locations in this heterogeneous

country. In places where access by route can be difficult, this content has potential

reach if there is an internet connection.

The format of the material prioritized videos representing the easiest way of consuming

information today, being passive and representing less effort, requiring only that

the person is watching and understanding. However, the material was created in PDF

to facilitate a quick visualization of the subjects covered. The creation of a project

website was conceived to centralize all these forms of communication in one unit,

allowing that when accessing this website, the participant can, in addition to accessing

the materials, have a form of contact with the team is behind its creation.

Early detection of skin cancer is the strategy that is believed to be the most cost-effective.

Most of them are directed at melanomas due to their greater morbidity and mortality,

but non-melanomas, due to their greater incidence, may represent even greater costs

to the health system10.

Early detection allows thinner lesions to be treated with a better prognosis in the

case of melanomas and allows for less extensive scarring with better aesthetic results11,12.

Many people have misconceptions about ultraviolet radiation, photoprotection, how

skin cancer arises, its types and characteristics13. This project then proves essential by bringing correct information to the lay population,

combating possible myths and wrong ideas.

Since the 1980s, with the “Sun Smart” campaign, Australia has been a pioneer country

in skin cancer prevention programs because it has the highest incidence of the disease

worldwide, representing a high health cost. An efficient strategy in this country

was to act locally, knowing the reality of the affected population. However, in today’s

connected world, an online project can reach a large portion of the population. Partnerships

between diverse sectors of the population, such as government, industry and medical

services, were also a key to Australian success. Consistency is also important, as

engagement and protective behaviors can fluctuate according to the intensity of exposure

to the campaign and the arrival of information to participants14,15. The online content is dynamic and can be changed in content and format to seek the

attention of a greater number of interlocutors to the subject. In the “Euromelanoma”

campaign, this has been one of the biggest challenges: maintaining the motivation

of professionals over time and reaching the high-risk population16,17.

Skin cancer screening outs the health system. The assistance of professionals alerted

after the PPA can be fundamental to reach high-risk people who do not usually go to

the doctor or who would not participate in a campaign. This exchange of information

is very positive. An American hairdresser who pioneered this role has been looking

for more than 20 years to look for suspicious injuries to her clients. She encourages

colleagues to take on this “double journey” that adds more value to their work and

offers broader care. Ironically, it was she who had a malignant injury detected by

one of her clients(.)

Lachiewicz et al., in 200819, raised in the literature the possibility of acquiring knowledge about skin cancer

by hairdressers because melanomas of the head and neck are the ones with the highest

mortality. As these professionals have intimate and frequent contact with these regions’

skin and attachment, they have a valuable opportunity for detection. This is the logic

of the PPA. Later other authors8 deepened this issue from the suspicion of skin lesions by hairdressers. They focused

on head and neck melanomas due to their mortality, but this concept can be extrapolated

to other lesions. There are standardized criteria that allow the suspicion of a malignant

skin lesion, even if the person is not a specialized doctor. Besides, they pointed

out other positive experiences in these professionals’ performance in health promotion

related to diseases, such as breast and prostate cancer. Beauty professionals are

an option that is still little used and has great potential for action. There is a

range of professionals who have frequent and prolonged access to the skin of the population.

However, to avoid any ethical dilemma, it is very important to emphasize to these

professionals that they help detect potential malignant lesions but that the effective

diagnosis, positive or negative, remains a medical responsibility.

Doran et al., in 201620, carried out a cost-effectiveness analysis of three Australian media campaigns in

New South Wales, concluding that they are a good investment due to their potential

to reduce the morbidity, mortality and economic burden caused for skin cancer. In

this analysis, there was a 3.85 dollars return for each dollar invested, which becomes

even more positive in a low-cost project like the PPA.

Beauty is very important in today’s society, especially in Brazil. According to SEBRAE

(Brazilian Service of Support to Micro and Small Enterprises), in 2014 there were

345,977 individual microentrepreneurs in Brazil in the field of “hairdressers, manicures

and pedicures.” This creates a very large social importance of these professionals,

who in certain places have a greater reach than the health services themselves, with

regularity, trust and proximity, which overcomes possible cultural gaps21.

Another point addressed by the PPA is the importance in media and society of the desire

to be tanned. According to Perez et al., in 201522, this desire is greater among young people, especially among women, very influenced

by fashion. The PPA highlights the sensitivity to ultraviolet radiation, the differences

between skin color tones and points out that the healthiest skin color is the one

we were born with, to mitigate erroneous beliefs that a white skin (pejoratively described

as “pale” ) is a sign of a less healthy person than the one who sustains a tan, at

the expense of exposure to skin cancer risks.

As perspectives for the future of this project, the establishment of partnerships

should be fundamental for the expansion and feeding of the project content and dissemination.

Volunteering is not something very present in Brazilians’ routine, so the real interest

of beauty professionals in acquiring this knowledge that does not bring an immediate

financial return is not yet known.

However, even with suspicion of malignant injury by a lay professional, this patient’s

gateway through the health system will be through family doctors in basic health units.

They, therefore, require more consistent training on skin cancer, which does not receive

much attention in the usual residency programs in family medicine23.

CONCLUSION

The “Projeto Pele Alerta” is an educational project in prevention and early detection

of skin cancer, aimed at professionals in the beauty and personal care market, which

is on the internet ready for use and to be disseminated throughout the Brazilian territory.

REFERENCES

1. Sociedade Brasileira de Dermatologia (SBD). Análise de dados das campanhas de prevenção

ao câncer da pele promovidas pela Sociedade Brasileira de Dermatologia de 1999 a 2005.

An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81(6):533-9.

2. Markuza AG, Book SE. Basal cell carcinoma: pathogenesis, epidemiology, clinical features,

diagnosis, histopathology, and management. Yale J Biol Med. 2015 Jun;88(2):167-79.

3. Gallagher RP, Lee TK. Adverse effects of ultraviolet radiation: a brief review. Prog

Biophys Mol Biol. 2006 Set;92(1):119-31.

4. Rigual NR, Popat SR, Jayprakash V, Jaggernauth W, Wong M. Cutaneous head and neck

melanoma: the old and the new. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2008 Jul/Ago;8(3):403-12.

5. Gandhi SA, Kampp J. Skin cancer epidemiology, detection, and management. Med Clin

North Am. 2015 Nov;99(6):1323-35.

6. Hamidi R, Peng D, Cockburn M. Efficacy of skin self-examination for the early detection

of melanoma. Int J Dermatol. 2010 Fev;49(2):126-34.

7. Rat C, Quereux G, Riviere C, Clouet S, Senand R, Volteau C, et al. Targeted melanoma

prevention intervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Ann Fam Med. 2014

Jan;12(1):21-8.

8. Roosta N, Wong MK, Woodley DT. Utilizing hairdressers for early detection of head

and neck melanoma: an untapped resource. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66(4):687-8.

9. Kienstra AM, Padhya TA. Head and neck melanomas. Cancer Control. 2005;12(4):242-7.

10. Hoorens I, Vossaert K, Pil L, Boone B, Schepper S, Ongenae K, et al. Total-body examination

vs lesion-directed skin cancer screening. JAMA Dermatol. 2016 Jan;152(1): 27-34.

11. Berwick M, Begg CB, Fine JA, Roush GC, Barnhill RL. Screening for cutaneous melanoma

by skin self-examination. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996 Jan;88(1):17-23.

12. Bariani RL, Nahas FX, Barbosa MVJ, Farah AB, Ferreira LM. Carcinoma basocelular: perfil

epidemiológico e terapêutico de uma população urbana. Acta Cir Bras. 2006;21(2):66-73.

13. Barber K, Searles GE, Vender R, Teoh H, Ashkenas J; Canadian Non-melanoma Skin Cancer

Guidelines Committee. Non-melanoma skin cancer in Canada chapter 2: primary prevention

of non-melanoma skin cancer. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015 Mai/Jun;19(3):216-26.

14. Oyebanjo E, Bushell F. A critical evaluation of the UK SunSmart campaign and its relevance

to black and minority ethnic communities. Perspect Public Health. 2014 Mai;134(3):144-9.

15. Sinclair C, Foley P. Skin cancer prevention in Australia. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(Supl

3):116-23.

16. Stratigos AJ, Forsea AM, Van Der Leest RJT, Vries E, Nagore E, Bulliard JL, et al.

Euromelanoma: a dermatology-led european campaign against nonmelanoma skin cancer

and cutaneous melanoma. Past, present and future. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167(Supl 2):

99-104.

17. Conejo-Mir J, Bravo J, Díaz-Pérez JL, Fernández-Herrera J, Guillén C, Martí R, et

al. Euromelanoma day. Results of the 2000, 2001 and 2002 campaigns in Spain. Actas

Dermosifiliogr. 2005;96(4):217-21.

18. Campos L. Hairdresser on double-duty. USF health communications [Internet]. 2007;

[acesso em 2016 Nov 20]. Disponível em: https://hscweb3.hsc.usf.edu/health/now/hairdresser-on-double-duty/index.html

19. Lachiewicz AM, Berwick M, Wiggins CL, Thomas NE. Survival differences between patients

with scalp or neck melanoma and those with melanoma of other sites in the Surveillance,

Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program. Arch Dermatol. 2008 Abr;144(4):515-21.

20. Doran CM, Ling R, Byrnes J, Crane M, Shakeshaft AP, Searles A, et al. Benefit cost

analysis of three skin cancer public education mass-media campaigns implemented in

New South Wales, Australia. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147665.

21. Wilson TE, Fraser-White M, Feldman J, Homel P, Wright S, King G, et al. Hair salon

stylists as breast cancer prevention lay health advisors for African American and

Afro-Caribbean women. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008 Fev;19(1):216-26.

22. Perez D, Kite J, Dunlop SM, Cust AE, Goumas C, Cotter T, et al. Exposure to the "dark

side of the tan" skin cancer prevention mass media campaign and its association with

tanning attitudes in New South Wales, Australia. Health Educ Res. 2015;30(2):336-46.

23. Eide MJ, Asgari MM, Fletcher SW, Geller AC, Halpern AC, Shaikh WR, et al. Effects

on skills and practice from a web-based skin cancer course for primary care providers.

J Am Board Fam Med. 2013 Nov/Dez;26(6):648-57.

1. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Discipline of Plastic Surgery, São Paulo, SP,

Brazil.

Corresponding author: Caroline Kroeff Machado Rua Botucatu , 740, 2º Andar, Vila Clementino, São Paulo, SP, Brazil Zip Code: 04023-062

E-mail: ck@ckplastica.com.br

Article received: February 02, 2020.

Article accepted: July 15, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none

COLLABORATIONS

CKM Conception and design study, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft

Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

AH Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval, Supervision,

Visualization

IDAOS onception and design study, Conceptualization, Final manuscript approval

LMF inal manuscript approval, Methodology, Supervision