INTRODUCTION

Rhinoplasty is a surgical procedure widely performed in plastic surgery. Only in

2017, according to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery

(ISAPS), approximately 877,254,000 rhinoplasties were performed worldwide1. An increase of about 11% in reports of

this surgery compared to the previous year of the research.

The development of knowledge of the nose’s anatomy is one of the most refined

teachings in plastic surgery. In addition to dedication and studies, it requires

visual technical experience for an adequate understanding of the structures and

ligaments that will be supported and ensure good physiology to guarantee

respiratory function2,3.

Considered by some as a technical and intellectual challenge, the surgical art of

nasal surgery challenges the surgeon at the beginning of the development of

learning even to the most experienced surgeons. Knowledge of patients’ profiles

submitted to this procedure facilitates surgical programming, making it possible

to evolve with longer-lasting results.

Brazil, like other countries4,(5,

)presents a population formed by a diversity of ethnicities with the

anatomy of the nose of the most varied forms. Studies on nasal anthropometry

are

frequent in theliterature5,6, but studies tracing the epidemiological

profile of patients undergoing rhinoplasty are not usual yet.

OBJECTIVE

This study aims to describe patients’ epidemiological profile submitted to

rhinoplasty at the Plastic Surgery Service of the Centro de Reabilitação

e Readaptação Dr. Henrique Santillo in Goiânia Goiás.

METHODS

This study analyzed the epidemiological profile of patients treated by the

plastic surgery team of the Centro de Reabilitação e Readaptação Dr.

Henrique Santillo (CRER). This one is a retrospective descriptive

observational study.

Patients submitted to rhinoplasty by the Plastic Surgery Service of CRER, aged

over 18 years, treated from January 2013 to December 2019, by the Unified Health

System (SUS) were included in the study. Patients who presented septum deviation

by clinical examination or tomography were treated in the same surgery. All

patients who required nasal reconstruction were excluded from this study.

Data were collected from the statistical database of plastic surgery patients in

the MV Soul®. All patients signed a free and informed consent

form. The Helsinki declaration principles were respected, and the work was

submitted to the internal ethics committee. The ethics committee approved the

study of Plataforma Brasil registered on the number CAAE

30798120.6.0000.5082.

Data were collected, such as age, gender, cause of rhinoplasty, type of

rhinoplasty access (whether open or closed), and aspects related to the

treatment of the nasal tip, nasal dorsum, septum, use and types of grafts,

fracture, and kind of dressing. The data were compiled in an

Excel program table, and the statistical analysis of the

data was performed with the description of absolute numbers and percentages.

RESULTS

A total of 179 patients were evaluated. Patients with rhinophyma and nose

reconstruction were excluded from these patients. The patients attended were

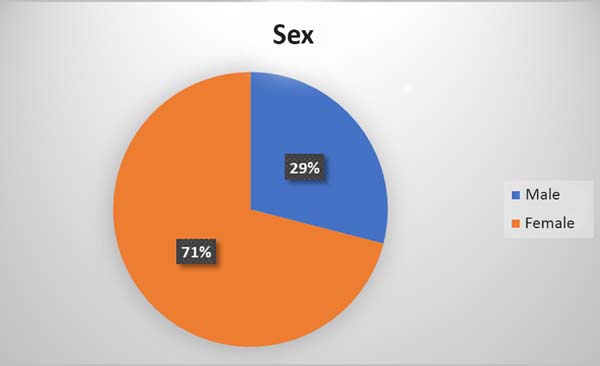

mostly female, totaling 71% (Figure 1). The

patients’ mean age was 35.5 years (19-67, SD =/- 11).

Figure 1 - Percentage of men and women.

Figure 1 - Percentage of men and women.

The main reasons that led patients to perform rhinoplasty were: deformities after

trauma 69 (41.5%), followed by rhinomegaly 34 (20.5%), rhinomegaly with septal

deviation 33 (19.8%), purely aesthetic causes 15 (9.0 %), cases of congenital

deformity 10 (6.0%) and others (3.0%) (Table 1).

Table 1 - Causes that motivated rhinoplasty.

| Rhinoplasty reason |

N |

% |

| Trauma |

69 |

41.5 |

| Rinomegalia |

34 |

20.5 |

| Rinomegaly with septum deviation |

33 |

19.8 |

| Aesthetic |

15 |

9.0 |

| Congenital deformity |

10 |

6.0 |

| Other |

5 |

3.0 |

| Overall total |

166 |

|

Table 1 - Causes that motivated rhinoplasty.

Most cases were primary rhinoplasty 127 (76.5%), and 39 were secondary

rhinoplasty (23.5%) (Table 2). Data

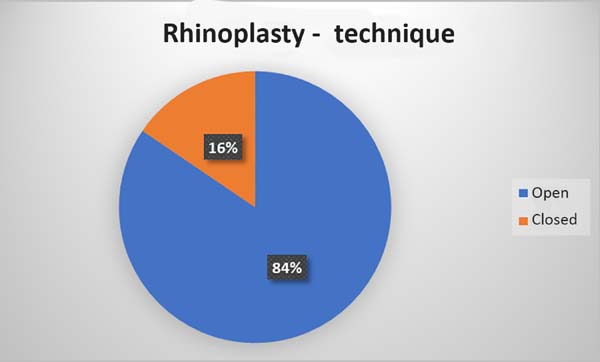

excluded: patients with rhinophyma. Regarding access, 147 cases (84.5%) by the

open technique and 27 (15.5%) closed-route cases (Figure 2).

Table 2 - Primary versus secondary rhinoplasty.

| Rhinoplasty |

Primary |

Secondary |

| |

127 (76.5%) |

39 (23.5%) |

Table 2 - Primary versus secondary rhinoplasty.

Figure 2 - Rhinoplasty approach.

Figure 2 - Rhinoplasty approach.

Fifteen patients in this service were reapproached to a secondary rhinoplasty

(9.0% surgical retouch rate); the remaining 24 came from other public and

private services. Ten patients were initially treated with closed technique,

and

5 with the open technique of the patients reapproached in this service. The

areas that required reapproach were: nasal tip (7), dorsum (4), triangular

cartilage region (2), and intranasal alteration as recurrence of septum

deviation (2).

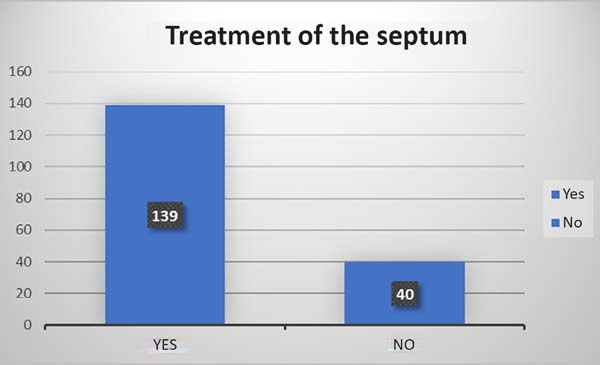

In 139 cases (83.8%), septal treatment was performed either by septoplasty or

another method (Figure 3). The dorsum was

treated in 131 (78.9%) cases, with the predominant tactic being scraping along

with osteocartilaginous resection (Table 3).

Figure 3 - Treatment of the septum.

Figure 3 - Treatment of the septum.

Table 3 - Back treatment.

| Tactic |

Number of cases |

| Costal cartilage |

5 |

| Onlay graft |

8 |

| Osteocartilaginous scraping |

32 |

| Scraping + Osteocartilaginous re-section |

48 |

| Diced cartilage |

5 |

| Turkish graft "Turkish delight" |

2 |

Table 3 - Back treatment.

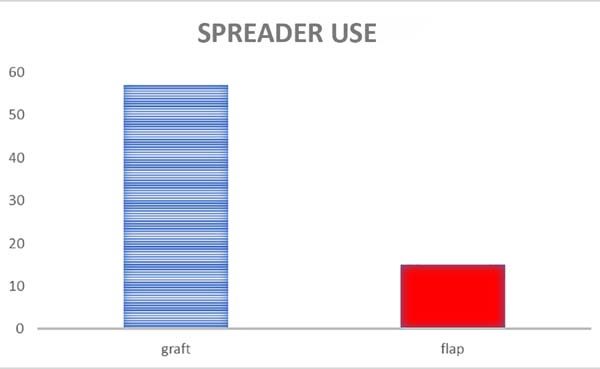

The use of spreader grafts or reaver flaps totaled 72 (43.3%)

cases. Among these reavers, the majority were spreader grafts,57 out of 72 (79%)

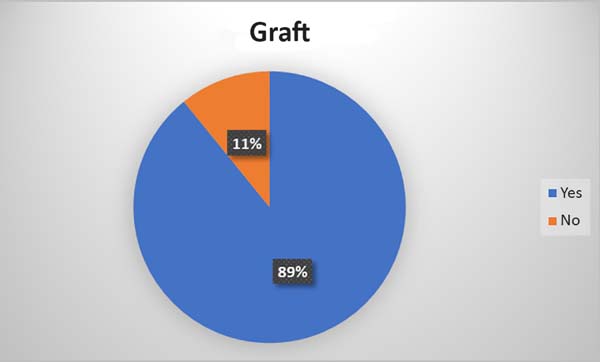

and 15 cases of spreader flap Shaline flaps,15 out of 72 (21%) (Figure 4). A total of 148 (89%) patients

underwent rhinoplasty using some graft type (Figure 5).

Figure 5 - Use of rhinoplasty grafts.

Figure 5 - Use of rhinoplasty grafts.

Regarding the tip, 136 (81.9%) rhinoplasties reported treatment, using as main

tactics in 110 of 136 cases (80.8%) the performance of columellar structure

associated with inter and intradomal suture, regarding the fracture of the nasal

bones during rhinoplasty, 105 (60.3%) patients.

In 126 cases (75.9%), intra or extra nasal splint was used regarding the

dressing. Regarding postoperative complications, a total of18 cases (10.8%) were

observed. Of these, two patients evolved with hyperemia in the nose region, 2

with sinusitis, 5 with persistence of respiratory difficulty by structural

alteration, such as persistent septum deviation or internal nasal valve

(secondary rhinoplasty), 1 with hematoma, four bone calluses, one local

infection, and three suture dehiscences (1 in donor area).

DISCUSSION

In this study, it was observed that most patients were female, with a mean age of

33.04 years. Previous trauma to the nose was the main motivating factor for

rhinoplasty. In the literature, unfortunately, there is a scarcity of data on

the aspects of the epidemiological profile of patients undergoing rhinoplasty,

but studies relating to nose trauma show a prevalence in male patients7,8,

in contrast to females’ prevalence. Probably women are more concerned with the

changes generated by the trauma to the nose and seek the correction of this more

quickly than men; this factor is well observed when we see that the demand for

plastic surgeries is predominant in women9. In nasal trauma, man is more exposed, either by motorcycle accidents

or by violence or practice of contact sports8

10. However, men tend to leave the

surgical approach for a later time.

In this study, a prevalence of primary rhinoplasties was observed through open

access. Among those who were closed-access, eight patients had to undergo a new

rhinoplasty openly, showing that these patients with nose trauma and deformities

need a broader visualization to correct the abnormalities more accurately11,12. Although most approaches were open in this study, the literature

has shown that the choice of open or closed surgical approach for correction

of

the nasal structures is related to the surgeon’s experience and that the fact

that it is open or closed does not interfere with the increase of

complications13,14.

In most cases, treatment of the dorsum was performed, with predominant scraping

with osteocartilaginous resection. The use of grafts was prevalent, 92.83%,

corroborating the literature on the importance of structured rhinoplasty in

these complex cases15-17.

The spreader graft had a slight predominance over the “spreader flap.” The use of

the”spreader graft” was first described by Sheen in 198418, in an attempt to restore the function of the internal

nasal valve; the “spreader flap” has the same objective, but no need to use a

graft. The spreader also assists in the rectification of septum19,20. The presence of greater use of”spreader graft” in this group

happens because it permits the rectification and preservation of the internal

nasal valve’s function with the restoration of the nasal middle third. Necessary

due to these patients’ characteristics, related to nasal trauma and previous

deformities, hindered breathing, such as septal deviation.

The tip’s treatment was present in most cases where the preparation of columellar

structure associated with inter and intradomal sutures was quite frequent. Such

surgical tactics improve the nose’s structure and the tip’s definition (Figure 5)21,22.

Regarding the fracture of the nasal bones during rhinoplasty, 80 patients

underwent the technique, while 35 patients did not require it. This procedure

is

important in maintaining the nose lines and correction of open dorsum in

secondary surgeries23-25. The high frequency of the use of bone

fractures in this study may be related to the critical incidence of nasal trauma

in this population.

Regarding the dressing, in 48 cases (57.83%), external splints were used, 30.12%

did not use it, and in 12.04%, there was no report. External splints are

traditional in rhinoplasties with osteotomies since their beginning, since when

they are used correctly, they allow adequate protection and reorganization of

bone alignment26. Regarding postoperative

complications, two cases of a total of 83 patients were observed. One patient

evolved with hyperemia in the nose region and another with sinusitis. Both were

treated with oral antibiotics, evolving well, without further complications.

This descriptive retrospective study presents limitations related to its

retrospective, descriptive observational characteristic. It is performed in only

one reference center, so all biases related to descriptive studies are involved

in this study, such as highly selected studied individuals, absence of control

group, and researcher bias.

CONCLUSION

In the study on the profile of patients submitted to rhinoplasty at the plastic

surgery service of the Centro de Reabilitação e Readaptação Dr. Henrique

Santillo, the profile of the patients found was female, with a mean

age of 35.5 years, mainly seeking surgery due to nasal deformity after trauma

and requiring the use of cartilage grafts for correction. Studies on

epidemiology in rhinoplasty are scarce. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct

further studies in several centers to determine which epidemiological profile

is

the most common.

REFERENCES

1. International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS).

Procedures performed in 2017 [Internet]. New York: ISAPS; 2017; [acesso em 2019

Fev 19]. Disponível em: www.isaps.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/ISAPS_2017_International_Study_Cosmetic_Procedures.pdf

2. Yeolekar A, Qadri H. The learning curve in surgical practice and its

applicability to rhinoplasty. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg.

2018;70:38-42.

3. Crosara PF, Nunes FB, Rodrigues DS, Figueiredo ARP, Becker HMG,

Becker CG, et al. Rhinoplasty complications and reoperations: systematic review.

Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jan;21(1):97-101.

4. Rohrich RJ, Bolden K. Ethnic rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2010

Abr;37(2):353-70.

5. uri

6. Gunter JP, Rohrich RJ, Adams Junior WP. Dallas rhinoplasty: nasal

surgery by the masters. 2nd ed. St Louis: Quality Medical Publishing;

2007.

7. Pochat VD, Alonso N, Meneses JVL. Avaliação funcional e estética da

rinoplastia com enxertos cartilaginosos. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2010;25(2):260-70.

8. Cruz GAO, Maluf Junior I, Maluf RCP, Kurogi AS, Berri DT, Lopes MAC,

et al. Fraturas nasoetmoideorbitais: experiência de 37 anos do Serviço de

Cirurgia Craniofacial do Hospital de Cajuru e Hospital do Trabalhador. Rev Bras

Cir Plást. 2013;28(3):507-10.

9. Motta MM. Análise epidemiológica das fraturas faciais em um hospital

secundário. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2009;24(2):162-9.

10. Bayram Y, Yapici AK, Zor F, Bozkurt M, Kilic S, Ozturk S, et al.

Late correction of traumatic nasal deformities: a surgical algorithm and

experience in 120 patients. Aesthet Surg J. 2018 Dez;38(12):NP182-NP95. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1093/asj/sjy155

11. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP). Análise

comparativa das pesquisas 2009 e 2015. Situação da cirurgia plástica no Brasil

[Internet]. São Paulo: SBCP; 2016 [acesso em 2019 Abr 16]. Disponível em:

http://www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br/restrito/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/pesquisa-SBCP-2009-14.pdf

12. Rohrich RJ, Raniere Junior J, Ha RY. The alar contour graft:

correction and prevention of alar rim deformities in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 2002;109:2495-505;discussion:2506-8.

13. Cafferty A, Becker DG. Open and closed rhinoplasty. Clin Plast Surg.

2016 Jan;43(1):17-27. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2015.09.002

14. Kütük GS, Arikan OK. Evaluation of the effects of open and closed

rhinoplasty on the psychosocial stress level and quality of life of rhinoplasty

patients. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2019 Ago;72(8):1347-54. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2019.03.020

15. Rosenberger ES, Toriumi DM. Controversies in revision rhinoplasty.

Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2016 Ago;24(3):337-45. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsc.2016.03.010

16. Wong BJF, Friedman O, Hamilton GS. Grafting techniques in primary

and revision rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2018

Mai;26(2):205-23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsc.2017.12.006

17. Rohrich RJ, Afrooz PN. Rhinoplasty refinements: the role of the open

approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017 Out;140(4):716-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000003743

18. Sheen JH. Spreader graft: a method of reconstructing the roof of the

middle nasal vault following rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984

Fev;73(2):230-9.

19. Oneal RM, Berkowitz RL. Upper lateral cartilage spreader flaps in

rhinoplasty. Aesthet Surg J. 1998 Set/Out;18(5):370-1.

20. Kovacevic M, Wurm J. Spreader flaps for middle vault contour and

stabilization. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2015 Fev;23(1):1-9. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fsc.2014.09.001

21. Guyuron B, Behmand RA. Nasal tip sutures part II: the interplays.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003 Set;112(4):1130-45;discussion:1146-9.

22. Toriumi DM. New concepts in nasal tip contouring. Arch Facial Plast

Surg. 2006 Mai/Jun;8(3):156-85.

23. Rohrich RJ, Muzaffar AR, Janis JE. Component dorsal hump reduction:

the importance of maintaining dorsal aesthetic lines in rhinoplasty. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(5):1298-308;discussion:1309-12.

24. Ahmad J, Rohrich RJ, Lee MR. Surgical management of the nasal

airway. In: Rohrich RJ, Adams Junior WP, Ahmad J, Gunter JP, eds. Dallas

rhinoplasty: nasal surgery by the masters. 3rd ed. St Louis: Quality Medical;

2014. p. 975-98.

25. Slupchynskyj O, Rahimi M. Revision rhinoplasty in ethnic patients:

pollybeak deformity and persistent bulbous tip. Facial Plast Surg. 2014

Ago;30(4):477-84.

26. Varedi P, Bohluli B. Do the size and extension of the external nasal

splint have an effect on the osteotomy, brow lines, and long-term results of

rhinoplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial of 2 methods. J Oral

Maxillofac Surg. 2015;73(9):1843.e1-e9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joms.2015.05.027

1. Centro Estadual de Reabilitação e Readaptação

Dr Henrique Santillo, Goiânia, GO, Brazil.

2. Federal University of Goiás, Plastic Surgery,

Goiânia, GO, Brazil.

3. Hospital Estadual de Urgências Governador

Otávio Lage de Siqueira, Goiânia, GO, Brazil.

4. The Rhinoplasty Society, Plastic Surgery

Rhinoplasty, Goiânia, GO, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Fabiano Calixto Fortes Arruda

Rua T 50, 723, Setor Bueno, Goiânia, GO, Brazil. Zip Code: 74215-200 E-mail:

arrudafabiano@hotmail.com

Article received: November 14, 2019.

Article accepted: July 15, 2020.

Conflicts of interest: none