INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is the most common non-cutaneous malignancy among women worldwide,

accounting for approximately 28% of new malignant tumor cases each year in

Brazil. In the biennium 2016-2017, the Brazilian National Cancer Institute

(Instituto Nacional do Câncer; INCA) estimated approximately 2,160 new cases in

the state of Ceará and 57,960 new cases of breast cancer for every 100,000 women

in Brazil1.

The breasts represent one of the most eloquent symbols of female sexuality,

adorning the female body, and any condition that compromises its structure

brings serious consequences to the patient’s physical and psychological

well-being.

The high incidence of breast cancer and the importance of the breasts for a good

quality of life in patients made breast reconstructions after mastectomy an

integral part of the cancer treatment plan.

In 1894, William Halsted published in the United States the technique known today

as classical radical mastectomy, which relies on total withdrawal of the breast

with an adequate margin of safety in the adjacent skin and subcutaneous tissue,

in monobloc, by removing the pectoralis major and minor muscles and the adipose

tissues in the region, which includes the axillary lymph nodes2. However, this technique greatly

compromised breast reconstructions as the skin was not preserved.

Over the years, more conservative techniques have emerged, such as the one

advocated by Patey, which preserves the pectoralis major muscle, and the Madden

technique, which preserves both the pectoralis muscles.

To progressively perform more conservative mastectomies, the skin-sparing

mastectomy was developed, which may or may not preserve the nipple-areola

complex (NAC) and emerged as a procedure that improved the reconstructed

breasts, using no less complex techniques, but less debilitating for the

reconstruction, through implants with alloplastic material. Preservation of the

breast skin envelope provides a satisfactory color tone, texture, and contour of

the reconstructed breast, either with a tissue expander, alloplastic implant,

lipografting, or deepidermized flaps2.

The use of prosthetic implants for breast reconstructions started in the early

1960s with implants filled with silicone gel. Over the years, implant technology

and surgical techniques have evolved, resulting in an improved quality of the

reconstructed breast3.

Alloplastic implants can be classified according to shape (round, natural,

anatomical, and conical), texture (smooth, textured, and coated with

polyurethane foam), and projection (high, extra-high, moderate, and low)4. The choice of implant is fundamental to

the normal and natural shape, providing more femininity to the thorax.

Breast reconstruction with an alloplastic implant presents early and late

surgical complications that are directly or indirectly related to the surgical

technique used to perform mastectomy and implantation of a synthetic

material.

OBJECTIVE

To analyze the complications found in a group of patients submitted for immediate

breast reconstructions using conical and non-conical prostheses performed in our

service from January 2016 to 2018.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional, retrospective, observational cohort study that

analyzed the medical records of patients who were submitted for skin-sparing

total mastectomies due to breast cancer, with immediate breast reconstruction

using an extra-high conical prosthesis coated with polyurethane or a non-conical

prosthesis, performed by the Plastic Surgery and Reconstructive Microsurgery

Service at the Walter Cantídio University Hospital of the Federal University of

Ceará, in Fortaleza, CE.

Patients who had an outpatient follow-up of at least 6 months and whose

reconstruction did not require local or distant skin flaps were included. Those

who had an outpatient follow-up of <6 months or those who used local or

distant flap for breast reconstruction were excluded.

All breast implants were placed in the submuscular position, using the pectoralis

major muscle and serratus anterior muscle to create the pocket, followed by

muscular suture to connect the edges after placing the prosthesis. To finish the

procedure, the subcutaneous region was drained using a vacuum, which was removed

after a daily rate of ≤30 mL of the sero-hematic secretion was achieved.

RESULTS

The mean age of the patients was 47.1 years, ranging from 27 to 71 years.

Immediate total breast reconstruction using a direct prosthesis after mastectomy

due to breast cancer was performed in 24 patients, with 13 (54.2%)

reconstructions performed with non-conical prostheses and 11 (45.8%) with

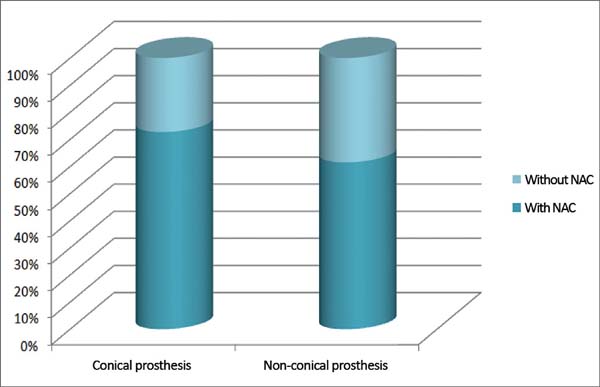

conical prostheses. The NAC was preserved in 8 (72.7%) patients with conical

prostheses and in 8 (61.5%) with non-conical prostheses; however, the NAC in 3

(27.3%) patients with conical prostheses and in 5 (38.5%) with non-conical

prostheses was not preserved (Figure 1).

Regarding the reconstructed side, 12 procedures were performed on the right

breast and 12 on the left breast.

Figure 1 - Proportion of conical and non-conical prostheses in all analyzed

patients who underwent breast reconstruction and their relation with

the nipple-areola complex (NAC) preservation.

Figure 1 - Proportion of conical and non-conical prostheses in all analyzed

patients who underwent breast reconstruction and their relation with

the nipple-areola complex (NAC) preservation.

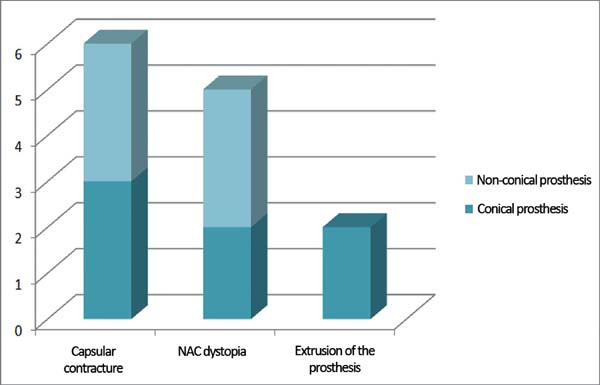

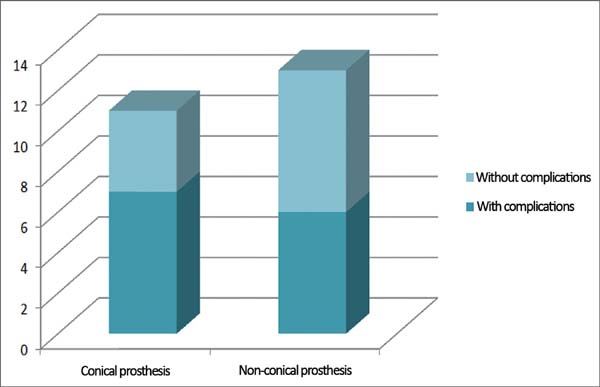

Complications occurred in 13 (54.1%) patients, with capsular contracture that

occurred in 6 (25%) patients as the most common (Figure 2). In patients with conical prostheses, 3 experienced

capsular contractures, 2 NAC dystopias (Figure 3) and 2 sore flaps with the formation of a hyperemic halo (Figure 4), similar to a pressure ulcer at

the tip of the conical prosthesis, which resulted in extrusion (Figure 5) and prosthesis removal. In

patients with non-conical prostheses, 3 capsular contractures and 3 NAC

dystopias occurred (Figure 6).

Figure 2 - Capsular contracture.

Figure 2 - Capsular contracture.

Figure 3 - Dystopia of the nipple-areola complex (NAC).

Figure 3 - Dystopia of the nipple-areola complex (NAC).

Figure 4 - Hyperemic halo at the tip of the conical prosthesis.

Figure 4 - Hyperemic halo at the tip of the conical prosthesis.

Figure 5 - Extrusion of the prosthesis.

Figure 5 - Extrusion of the prosthesis.

Figure 6 - Frequency and types of complications in all analyzed patients who

underwent immediate breast reconstruction and their relation with

the use of conical and non-conical prostheses.

Figure 6 - Frequency and types of complications in all analyzed patients who

underwent immediate breast reconstruction and their relation with

the use of conical and non-conical prostheses.

No infection or death was found in this group of patients. Regarding the

preservation of NAC, 8 (50%) patients with preserved NAC had complications,

whereas 5 (62.5%) patients with no preserved NAC had complications.

No difference in the frequency of complications was observed between the right

and left breasts, since both presented an incidence of 50% of complications.

Conical prostheses presented the highest number of complications, with

complications in 7 (63.6%) patients, whereas only 6 (46.1%) patients with

non-conical prostheses had complications (Figure 7). In 6 patients submitted for radiotherapy, 2 (33.3%) had capsular

contracture as a complication, whereas among the 18 patients who did not undergo

radiotherapy, 4 (22.2%) had capsular contracture.

Figure 7 - Frequency of the use of conical and non-conical prostheses in the

immediate and total breast reconstruction cases analyzed and the

relation with the frequency of complications.

Figure 7 - Frequency of the use of conical and non-conical prostheses in the

immediate and total breast reconstruction cases analyzed and the

relation with the frequency of complications.

DISCUSSION

In the recent years, breast reconstruction for the treatment of breast cancer has

become essential for mastectomized patients due to its proven psychological and

physical benefits, because it allows faster return to social life, in addition

to an improved immunity, thus contributing to a more favorable prognosis5,6.

Choosing the format of the prosthesis directly influences the shape of the

reconstructed breast, providing a better superomedial projection in round

prostheses, a better anterior projection in conical prostheses and a more

natural appearance in anatomical prostheses for more hypotrophic breasts.

In this study, complications occurred in 54.1% of patients using the alloplastic

material, which is higher than most breast reconstruction services, with the

incidence ranging from 30% to 43%7,8.

The most common complication identified was capsular contracture, which occurred

in 6 (25%) patients, which is similar to that found in the researched

literature, ranging from 0.5% to 30%9,10.

The most serious complication identified was prosthetic extrusion that required

removal of the prosthesis that occurred in 2 patients who used the conical

prosthesis, representing 18.1% of the patients. This incidence was higher than

that of a previous study, which ranged from 1.2% to 5.3%, and higher than those

using non-conical prostheses, in which no cases of prosthetic extrusion were

observed11.

Extrusions occurring in the conical prostheses initially evolved from a sore area

(local hyperemic halo) formed in the myocutaneous flap on the tip of these

conical prostheses, with characteristics similar to pressure ulcers (Figures 4 and 5).

CONCLUSION

Immediate breast reconstructions with silicone prostheses is an excellent option

for selected patients, considering the low complexity of the procedure and short

surgical time; however, the disease severity, associated with the surgeon’s

experience in performing the mastectomy and the skin flap thickness, may weaken

the cutaneous cover of the prosthesis, which promotes extrusion.

Our study showed a higher frequency of complications in immediate breast

reconstructions with conical and non-conical prostheses when the NAC was not

preserved and when the patient is submitted for radiotherapy, which were

observed in patients using conical prostheses. This condition mainly occurs due

to the formation of a sore area at the tip of the conical prosthesis that

resulted in extrusion.

COLLABORATIONS

|

ROR

|

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analysis; funding

applications; data collection; study design; resource management;

research; methodology; and writing (preparation of the original

manuscript).

|

|

SGPP

|

Final approval of the manuscript; conceptualization; project

management; writing (review and editing); supervision; and

observation.

|

REFERENCES

1. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José

Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2016: Incidência de Câncer de Mama no

Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2016. [acesso 2018 Mar 12]. Disponível em:

http://santacasadermatoazulay.com.br/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/estimativa-2016-v11.pdf

2. Mélega JM. Cirurgia Plástica Fundamentos e Arte: Princípios Gerais.

2a ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2011.

3. Grabb WC, Smith JW. Cirurgia Plástica. 6a ed. Rio de Janeiro:

Guanabara Koogan; 2009.

4. Pitanguy I. Cirurgia Plástica: Uma visão de sua amplitude. 1a ed.

São Paulo: Atheneu; 2016.

5. Veiga DF, Veiga-Filho J, Ribeiro LM, Archangelo I Jr, Balbino PF,

Caetano LV, et al. Quality-of-life and self-esteem outcomes after oncoplastic

breast-conserving surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2010;125(3):811-7.

6. Bellino S, Fenocchio M, Zizza M, Rocca G, Bogetti P, Bogetto F.

Quality of life of patients who undergo breast reconstruction after mastectomy:

effects of personality characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg.

2011;127(1):10-7.

7. Almeida Júnior GL, Macedo JLS, Borges SZ, Souza AO, Henriques FAM,

Suschino CMH, et al. Reconstrução mamária imediata após cirurgia conservadora do

câncer de mama. Rev Soc Bras Cir Plást. 2007;22(1):10-8.

8. Bronz G, Bronz L. Breast reconstruction with skin-expander and

silicone prostheses: 15 years' experience. Aesthetic Plast Surg.

2002;26(3):215-8.

9. D'Alessandro GS, Povedano A, Santos LKIL, Santos RA, Góes JCS.

Reconstrução mamária imediata com retalho do músculo grande dorsal e retalho de

silicone. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2015;30(2):163-71.

10. Mathes SJ, Hentz VR. Plastic surgery. 2a ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;

2006. p. 26-33.

11. Farah AB, Nahas FX, Mendes JA. Reconstrução mamária em dois estágios

com expansores de tecido e implantes de silicone. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2015;30(2):172-81.

1. Hospital Universitário Walter Cantídio,

Universidade Federal do Ceará, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Rogério de Oliveira Ribeiro, Rua Odilardo

Silva, nº 81 - Laguinho - Macapá - AP - Brazil , Zip Code 68908-182. E-mail:

roimed@yahoo.com.br

Article received: August 5, 2018.

Article accepted: October 4, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.