INTRODUCTION

Burns are tissue injuries resulting from various sources capable of producing

heat1 and are a global public health

problem responsible for approximately 180,000 deaths/year in low- and

middle-income countries and considered the fifth cause of death in the

world2. In children, burns are

responsible for negative impacts due to their severity, management difficulties,

potential mortality, and physical and psychological consequences, both for the

victim and their family environment3.

They have different etiologies, including scalds, flames, electrical voltage,

acidic or basic chemicals, and ultraviolet radiation4, responsible for small burns, easily treated, or

high-grade injuries, with irreversible consequences5. The organism responds locally or systemically, the first

due to direct damage to the tissue, while the second results from indirect

damage, that is, several physiological mechanisms try to contain the injury6. The severity and degree of injuries are

directly related to the etiological agent, the intensity of the heat, the

location affected, and the exposure time7,8.

In childhood, burns are the second most common cause of accidents, the fifth

cause of non-fatal pediatric injuries2,9, and the third cause of

death9. More than 111 thousand

children are hospitalized due to accidents or unintentional injuries, such as

burns, which cause around 3.6 thousand deaths/year10 and represent approximately 6% of deaths among the age

groups from 0 to 14 years old11.

Younger children are more vulnerable to domestic accidents such as burns due to

less motor coordination caused by physical immaturity, heightened curiosity, and

greater dependence on parents and caregivers12. Males have an increased risk in all age groups, with 1.5 boys

for every girl suffering from burns, and 53.4% of boys, from the first year of

life, have twice the chance of suffering injuries13. This higher proportion may be associated with behavior and

cultural factors, which determine greater freedom for boys, who expose

themselves to risky games14,15.

In the United States of America (USA), burns are the fourth leading cause of

death from trauma3,16 and, in children under 16 years of age, according to the

National Burn Repository, hospitalizations account for 20%17. In Brazil, around 1 million people suffer accidents

involving burns and only 100,000 seek medical help after the incident18.

Financial costs vary depending on the extent of the injury, length of stay,

number of interventions, and treatment method19. Treating burns requires a great economic burden, according to

clinical and surgical management, which includes a trained multidisciplinary

team, and long hospitalization time, associated with procedures, medications,

and equipment20.

In the USA, the direct costs of caring for children suffering from burns are more

than US$211 million, between 3000 and 5000 dollars/day, and corresponds to

approximately 23% of the total cost of treatment2. In Brazil, approximately R$450 million was spent on

hospitalizations due to burns in the last decade21. However, there are not enough studies that evaluate details of

the cost of hospitalization of burn victims22. A study that analyzed 180 burn patients for 5,207 days estimated

that the direct daily treatment costs were US$1,330.48 and the total

hospitalization cost was US$39,594.9019.

Furthermore, burn survivors spend less than non-survivors and, between direct

and indirect costs, each patient costs US$88,21819,22.

In addition to the financial cost, burns have social costs from indirect causes

such as unemployment, prolonged care, emotional trauma, and family

assistance2. The stigma caused by

burns is considered an obstacle by patients, as it interferes with

self-perception and self-esteem and leads victims to feelings of

self-depreciation23. Approximately

half of burns occur in children and adolescents, which has individual and social

consequences24.

According to the World Health Organization, burn injuries are more frequent in

underdeveloped countries, given that there is more medical care among children

of lower socioeconomic status and that public policies, prevention measures

implemented by the government, and low social, economic, and cultural factors

are reasons for the higher prevalence in these locations2,24.

Therefore, knowing the temporal trend of hospitalizations for pediatric burns in

all Brazilian regions could contribute to the planning of public policies aimed

at preventing and reducing social and financial costs for hospital

admissions.

OBJECTIVE

Thus, the objective of the study was to investigate the temporal trend of

hospitalizations for pediatric burns, in the age group from 0 to 14 years, in

Brazil, between 2012 and 2022.

METHOD

This is an ecological time series study with information regarding hospital

admissions for pediatric burns in Brazil. The data were obtained from the public

domain website Hospital Information System of the Unified Health System

(SIH-SUS), available at the Information Technology Department of the Unified

Health System (DATASUS). Information about hospital admissions in the SUS is

stored based on data from the Hospital Admissions Authorization (AIH). The data

were exported in comma-separated values (CSV) format and saved in an Excel

spreadsheet to calculate the rates.

Population demographic information was collected on the website of the Brazilian

Institute of Geography and Statistics, using the 2000 and 2010 censuses, in

addition to their intercensal estimates. Data from 91,091 children of under 14

years of age, both sexes, residing in the Brazilian regions (North, Northeast,

South, Southeast, and Central-West), victims of burns (International Statistical

Classification of Diseases and Problems Related to Health T20-T32) between the

years 2012-2022. The variables analyzed were sex (male and female), age group

(< 1 year; 1 – 4 years; 5 – 9 years and 10 – 14 years), region (North,

Northeast, South, Southeast, and Central-West) and years analyzed

(2012-2022).

The variables used in the study that fall into the dependent category were:

general hospitalization rate, hospitalization rate by sex, age group rate by

sex, and region. The independent variable was the years used for the study.

For each year of the period under study, the rates of hospitalizations for burns

were calculated according to the dependent variables, for every 100,000

inhabitants based on the ratio between the total number of hospitalizations for

pediatric burns and the population referring to sex, age group/sex, and

regions.

To analyze the temporal trend study of hospitalizations for pediatric burns,

standardized coefficients and the method of simple linear regression, using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20.0. In this method,

standardized hospitalization rates were considered dependent variables and the

years of the study period as an independent variable, obtaining a model

estimated according to the formula Y = b0 + b1X, where Y = standardized

coefficient, b0 = mean coefficient of the period, b1 = mean annual increment and

X = year. The analysis of behavior (increase, decrease, or stability) and the

mean annual variation in the hospitalization coefficient was carried out based

on the evaluation of the value of the regression coefficient (P). The

statistical significance considered was p≤0.05.

As it is a research with secondary data, in the public domain and free access,

following Resolution of the National Health Council (CNS) no. 466, of December

12, 2012, and under the guidelines and standards of Resolution 510 /2016 of the

National Health Council, Article 1, Sole Paragraph, Items II, III and V, there

was no need for approval by the Ethics and Research Committee.

RESULTS

Data from 91,091 hospital admissions due to burns in children aged 0 to 14 years,

in Brazil, between 2012 and 2022 were analyzed. There was a trend towards

stability in the general hospitalization rate in Brazil, with an initial rate of

18.51 and a final rate of 18.73 hospitalizations/100,000 inhabitants (mean rate

17.963; β = 0.119; p = 0.163).

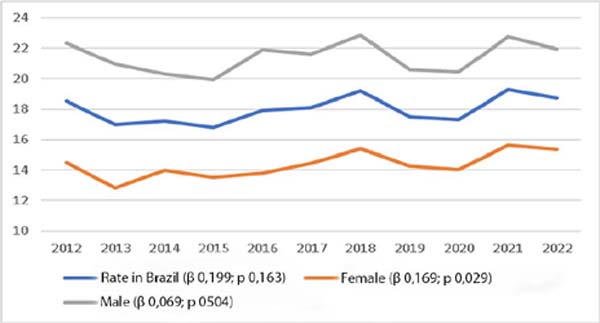

Concerning stratification by sex, the same stability behavior was observed in

males (mean rate of 21.42; β = 0.069; p =

0.504). The male hospitalization rate started at 22.33/100,000 inhabitants and,

at the end of the period, reduced to 21.95/100,000 inhabitants, resulting in a

1.7% reduction. In females, the behavior was an increase (mean rate 14.346;

β = 0.169; p = 0.029) in

hospitalizations/100,000 inhabitants, with an initial rate of 14.53, ending the

study period with 15.35/100,000 inhabitants, characterizing 5.5% increase (Table 1, Figure 1).

Table 1 - Temporal trend of hospitalizations due to burns, in the age group 0

-14 years, in 2012-2022, according to sex, age group, and

regions.

| Variables |

Mean Rate |

R (*) |

R2 (†) |

B (‡) |

95% CI |

p-value |

Trend |

| General Rate Sex |

17,963 |

0.451 |

0.204 |

0.119 |

(-0.580; 0.295) |

0.163 |

Stability |

| Masculine |

21,426 |

0.226 |

0.051 |

0.069 |

(-0.155; 0.293) |

0.504 |

Stability |

| Feminine |

14,346 |

0.654 |

0.427 |

0.169 |

(0.021; 0.316) |

0.029 |

Increase |

| Female Age Group |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4

years

|

29,281 |

0.698 |

0.488 |

0.407 |

(0.093; 0.722) |

0.170 |

Stability |

| 5 - 9 years |

9,614 |

0.286 |

0.082 |

0.084 |

(-0.127; 0.294) |

0.393 |

Stability |

| 10

- 14 years

|

5,684 |

0.195 |

0.038 |

0.034 |

(-0.095; 0.163) |

0.565 |

Stability |

| Male Age Group |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4

years

|

42,264 |

0.798 |

0.637 |

0.613 |

(0.265; 0.962) |

0.003 |

Increase |

| 5 – 9 years |

14,189 |

0.057 |

0.003 |

-0.210 |

(-0.300; 0.257) |

0.867 |

Stability |

| 10

– 14 years

|

9,871 |

0.754 |

0.569 |

-0.328 |

(-0.543; -0.113) |

0.007 |

Reduction |

| Regions |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| South |

26,952 |

0.861 |

0.741 |

1,091 |

(0.605; 1.577) |

0.001 |

Increase |

| Southeast |

13,748 |

0.615 |

0.378 |

0.172 |

(0.006; 0.338) |

0.440 |

Stability |

| Midwest |

23,689 |

0.004 |

0.000 |

0.006 |

(-1.133; 1.146) |

0.990 |

Stability |

| North |

12,267 |

0.082 |

0.007 |

-0.022 |

(-0.226; 0.182) |

0.600 |

Stability |

| North East |

19,881 |

0.638 |

0.407 |

-0.291 |

(-0.557; -0.026) |

0.350 |

Stability |

Table 1 - Temporal trend of hospitalizations due to burns, in the age group 0

-14 years, in 2012-2022, according to sex, age group, and

regions.

Figure 1 - Temporal trend of hospitalization for burns in Brazil, in the age

group 0-14 years, between 2012 and 2022, according to general rate

and sex.

Figure 1 - Temporal trend of hospitalization for burns in Brazil, in the age

group 0-14 years, between 2012 and 2022, according to general rate

and sex.

Table 1 presents the mean rate, the

coefficient of determination (R2), the mean annual variation (P), the value of

p, and the trend stratified by sex, age group, and region.

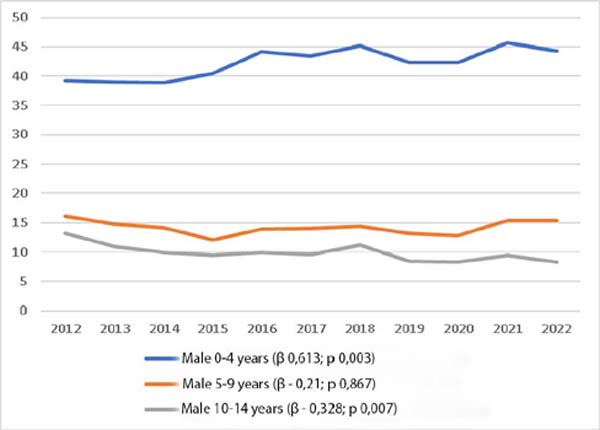

When analyzing the male age group, there was a tendency for an increase in

hospitalizations in the age group of 0 to 4 years (mean rate 42.264;

β = 0.613; p = 0.003), with an initial

rate of 39.23 and a final rate of 44.31, representing an increase of 13%. In the

age groups of 5 to 9 years and 10 to 14 years, there was stability (mean rate

14.189; β = -0.21; p = 0.867) and reduction

(mean rate 9.871; β = -0.328; p = 0.007) in

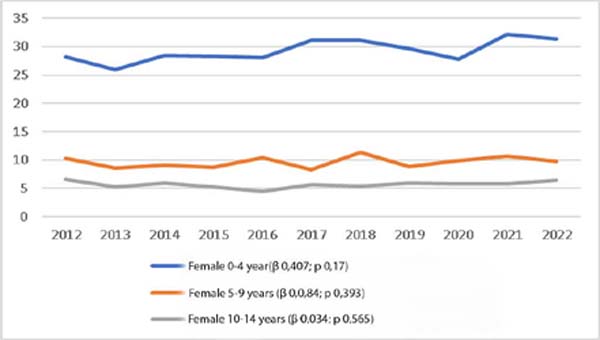

hospitalizations per 100,000 inhabitants, respectively (Table 1; Figure 2). In

the age groups by female sex, there was a stable trend in all age groups. In the

age group 0-4 years, there was an increase of 11.5%, with an initial rate of

28.14 and a final rate of 31.38 hospitalizations/100,000 inhabitants, with

stable behavior (Table 1; Figure 3).

Figure 2 - Temporal trend of hospitalization for burns in Brazil, among

males, according to age group.

Figure 2 - Temporal trend of hospitalization for burns in Brazil, among

males, according to age group.

Figure 3 - Temporal trend of hospitalization for burns in Brazil, among

females, according to age group.

Figure 3 - Temporal trend of hospitalization for burns in Brazil, among

females, according to age group.

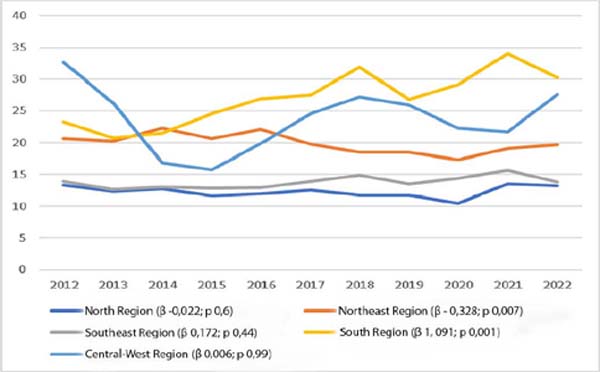

Regarding hospitalizations by region, an increase was observed in the South

Region (mean rate of 23.952; β = 1.091; p =

0.001), with 23.28 hospitalizations/100,000 inhabitants in the initial period of

the study and 30.21/100,000 inhabitants in the final period, reflecting a 29.8%

increase. The other regions showed stability behavior: North Region (mean rate

12.267; β = -0.022; p = 0.600), Northeast

Region (mean rate 19.881; β = -0.291; p = 0.035), Southeast

Region (mean rate 13.748; β = 0.172; p = 0.44)

and Central-West Region (mean rate 23.689; β = 0.006;

p = 0.99). The Central-West Region had the highest mean

rate of hospitalizations per 100,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the studied

period, with a value of 32.68/100,000 inhabitants.

The lowest mean rate of hospitalizations per 100,000 inhabitants, in the initial

period of the study, was obtained by the North Region, with a value of

13.29/100,000 inhabitants. At the end of the study period, except for the South

Region, which showed an increase in the mean hospitalization rate per 100,000

inhabitants, all regions behaved similarly with stability in mean

hospitalization rates (Table 1, Figure 4).

Figure 4 - Temporal trend in the hospitalization rate for burns in Brazil,

in the age group 0-14 years, between 2012 and 2022, according to

regions.

Figure 4 - Temporal trend in the hospitalization rate for burns in Brazil,

in the age group 0-14 years, between 2012 and 2022, according to

regions.

DISCUSSION

Studies on pediatric hospitalizations in the age group 0-14 years by region in

Brazil are scarce. The study under discussion verified a temporal trend of

stability in hospitalizations for pediatric burns in Brazil during the analyzed

period. On the other hand, a study of hospital admissions in Brazil in children

under 14 years of age, between 2008 and 2015, showed a downward trend in

hospitalizations25, with a reduction

of 28.14% for males and 22.2% for females, demonstrating behavior that diverges

from the current study.

The stability trend found in the present study can be explained by the adoption

of prevention measures such as the National Policy for Reducing Morbidity and

Mortality from Accidents and Violence (2001), the ban on the sale of liquid

alcohol to the general population (2002) and the creation of Accident and

Violence Prevention Centers in the Unified Health System (2004)25,26. Together, such actions receive support for the promotion of safe

and healthy behaviors and environments25,

supporting stability and a possible decrease in the trend of hospitalizations

over the years.

When analyzing the hospitalization rate for males, a stable behavior was observed

during the period studied, which differs from the literature, which shows an

increase in hospitalizations for males, with 61.4% of hospitalizations due to

burns in the age group of 0-14 years in the regions of Brazil in males between

2008-201525, as well as 69.4% of male

admissions to Burn Treatment Centers in children aged 7-12 years in the period

2011-201418. The observed behavior

may be a reflection of educational measures25,26 associated with the

child’s learning about the notion of danger, in addition to gaining strength and

agility according to their psychomotor development27.

As for females, there was a tendency for the general rate to increase, with

statistically significant data. In the literature, similar behavior occurred

only in the South Region, with a 23.25% increase in hospitalizations due to

burns25. The increase in the rate of

female hospitalization can be associated with domestic accidents and domestic or

self-inflicted violence18, since, due to

the complex interaction between family habits, cultural norms, socioeconomic

environment, and secular behaviors16,

females are often more likely to collaborate with household chores, susceptible

to greater contact with potentially flammable chemical substances.

Both males and females showed increases in the general rate of hospitalizations

in 2021. This increase may be associated with the COVID-19 pandemic period,

which encouraged children to remain at home, in which childhood burns

predominantly occur17, as well as other

accidents, most of which are unintentional and avoidable28.

Furthermore, with the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2020, the sale of 70º GL ethyl

alcohol in one-liter packages29 was

authorized for the hygiene of hands, surfaces, and objects; the sale of alcohol

with a strength greater than 54º GL was prohibited since 200225. Alcohol, among flammable agents, was

the one that caused the most burns in Brazil10,25 and with the ban on its

sale, there was a considerable reduction in these accidents, however, the

resumption of sales increased incidence again8.

There was a tendency towards stability in all age groups among females. Among

males, there was an increasing trend in the age group of 0-4 years, with

statistically significant data. This increase in this age group corroborates the

literature, which shows that the highest rates occurred in preschool children

aged 1-4 years, with 57.05% of hospitalizations, and mostly in males, with an

incidence of 63.04%26.

The increase in male hospitalizations in the 0-4 age group may be related to

increased curiosity and intellectual and cognitive development not accompanied

by the motor development of children at this age25, associated with the greater freedom provided to them12,18. Pediatric burns are the second most frequent cause of accidents

and the third cause of death among 0-14 years old11.

Concerning hospitalizations by region, the South Region was the only one that

presented statistically significant data, demonstrating an increase in the rate

of hospitalizations for pediatric burns, with an increase of 29.8% in

hospitalizations during the study period. The other regions showed stable

behavior. Therefore, the present study is in line with a similar study that

demonstrated an increase in hospitalizations for pediatric burns in the South

Region, in both sexes (males p = 0.050; females p = 0.033)25.

This fact may be related to the increase in notifications and better access to

specialized services that include rigor in hospitalizations in the pediatric age

group and availability of beds in the Burn Treatment Unit (BTU) of Hospital

Infantil Joana de Gusmão (HIJG) in Florianópolis, which is the only pediatric

BTU in southern Brazil25,28. Furthermore, it is pertinent to

highlight that some regions, such as the North, have large territorial

extensions, which can make access between the population and hospital care

difficult, as well as there are no units specialized in highly complex

burns25.

Regarding limitations, as the data were collected from hospital admission records

available in DATASUS, underreporting of hospitalizations due to burns or

erroneous notifications in the system may have occurred. Furthermore, since

DATASUS presents information relating to the Unified Health System,

hospitalizations for pediatric burns that occurred in the private network were

not included in the study analysis.

This study contributed to the identification of the temporal trend in

hospitalization rates for burns in the period 2012-2022 in the regions of Brazil

in the age groups of 0-14 years through the analysis of age group, sex, and

regions. In the literature, there is only one temporal trend study on

hospitalizations for pediatric burns by region, hence the relevance of this

study, when comparing hospitalization rates for burns between Brazilian regions.

Furthermore, the data found can contribute to the development of public health

policies, aiming at prevention and care at secondary and tertiary levels for the

populations studied.

CONCLUSION

In the period 2012 to 2022, there were 91,091 hospitalizations due to burns in

children aged 0-14 years in Brazil. Most of these occurred in the male

population 60.97% (n = 55,539) and in the age group 0-4 years 62.33% (n =

56,778). During the period studied, there was a stable trend in hospital

admissions for burns in Brazil in the population aged 0-14 years in males and an

increase in females.

Females behaved with stability at all ages, while males showed an increase in the

0-4 age group, stability in the 5-9 age group, and a reduction in the 10-14 age

group.

The regions behaved with stability in hospital admissions for pediatric burns,

except for the South Region, which showed an increase.

REFERENCES

1. Souza LRP, Lima MFAB, Dias RO, Cardoso EG, Briere AL, Silva JO. O

tratamento de queimaduras: uma revisão bibliográfica. Braz J Develop.

2021;7(4):37061-74.

2. World Health Organization (WHO). Burns. Geneva: WHO; 2018 [Acesso em

01 set 2022]. Disponível em: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns.

3. Hernández CMC, Núñez V P, Suárez FAP, Banqueris R F, García MS,

Mendoza D P. Queimaduras e sua prevenção em crianças. Rev Bras Queimaduras.

2020;19(1):84-8.

4. Kartal S P, Bayramgurler D. Hot Topics in Burn Injuries. IntechOpen.

2018;128.

5. Fé DSM, Germino C, Mendonça IB, Manso MEG. Queimadura: Efeitos

psicossociais nas vítimas. In: IV Congresso Médico Universitário São Camilo;

2018 Out 08-09; São Paulo, Brasil. Blucher Medical Proceedings; 2018. p.

170-92.

6. Sociedade Brasileira de Queimaduras; Escola Superior de Ciências da

Saúde, Liga de Emergência e Trauma da ESCS. Manual de queimaduras para

estudantes. Brasília: Sociedade Brasileira de Queimaduras;

2021.

7. Mehrotra S, Misir A. Special Traumatized Populations: Burns

Injuries. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2018;14(1):64-9.

8. Rosa Z, Lima TH. Perfil epidemiológico de pacientes vítimas de

queimadura. Braz J Health Rev. 2021;4(5):19832-53.

9. Gurgel AKC, Monteiro AI. Prevenção de acidentes domésticos infantis:

susceptibilidade percebida pelas cuidadoras. J Res Fundam Care Online.

2016;8(4):5126-35.

10. Santos G P, Freitas NA, Bastos VD, Carvalho F F. Perfil

epidemiológico do adulto internado em um centro de referência em tratamento de

queimaduras. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2017;16(2):81-6.

11. American Burn Association. National Burn Repository 2019 Update.

Report of data from 2009-2018. Chicago: American Burn Association;

2019.

12. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/contra-queimaduras-prevencao-e-a-vacina-06-6-dia- nacional-de-luta-contra-queimaduras/

13. Barcellos LG, Silva APP, Piva J P, Rech L, Brondani TG.

Characteristics and outcome of burned children admitted to a pediatric intensive

care unit. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30(3):333-7.

14. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde;

Departamento de Análise em Saúde e Vigilância de Doenças Não Transmissíveis.

Viva Inquérito 2017: Vigilância de Violências e Acidentes em Serviços Sentinelas

de Urgência e Emergência - Capitais e Municípios. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde;

2019.

15. Sociedade Brasileira de Queimaduras (SBQ). Secretaria de Justiça e

Cidadania. Casa segura, criança protegida: prevenção de acidentes domésticos com

crianças e adolescentes. Brasília: Sociedade Brasileira de Queimaduras;

2021.

16. Blank D. Controle de injúrias sob a ótica da pediatria contextual. J

Pediatr (Rio J). 2005;81(5 Suppl):S123-36.

17. Francisconi MHG, Itakussu EY, Valenciano PJ, Fujisawa DS, Trelha CS.

Perfil epidemiológico das crianças com queimaduras hospitalizadas em um Centro

de Tratamento de Queimados. Rev Bras Queimaduras.

2016;15(3):137-41.

18. Daga H, Morais IH, Prestes MA. Perfil dos acidentes por queimaduras

em crianças atendidas no Hospital Universitário Evangélico de Curitiba. Rev Bras

Queimaduras. 2015;14(4):268-72.

19. Anami EHT, Zampar E F, Tanita MT, Cardoso LTQ, Matsuo T, Grion CMC.

Treatment costs of burn victims in a university hospital. Burns.

2017;43(2):350-6.

20. Oliveira APBS, Peripato LA. A cobertura ideal para tratamento em

paciente queimado: uma revisão integrativa da literatura. Rev Bras Queimaduras.

2017;16(3):188-93.

21. Vieira VLM, Aquino DW, Siqueira L F, Silva JVS, Zanatta TG, Bender

CL, et al. A Média de permanência hospitalar por queimaduras e sua relação com

as despesas hospitalares no Brasil: uma análise epidemiológica da última década.

Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2021;20(Suppl 1):6.

22. Saavedra PAE. Perfil epidemiológico e estimativas de custos

hospitalares de vítimas de queimaduras [Tese de doutorado]. Brasília:

Universidade de Brasília Faculdade de Ceilândia; 2021. 149 p.

23. Emerick MFB, Batista KT. Principle of non-discrimination and

non-stigmatization: considerations for improving the quality of life of people

with burn sequelae. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2022;37(2):218-27.

24. Correia DS, Chagas RRS, Costa JG, Oliveira JR, França NPA, Taveira

MGMM. Perfil de crianças e adolescentes internados no centro de terapia de

queimados. Rev Enferm UFPE On Line. 2019;13(5):1361-9.

25. Pereima MJL, Vendramin RR, Cicogna JR, Feijó R. Internações

hospitalares por queimaduras em pacientes pediátricos no Brasil: tendência

temporal de 2008 a 2015. Rev Bras Queimaduras.

2019;18(2):113-9.

26. Souza TG, Souza KMD. Série temporal das internações hospitalares por

queimaduras em pacientes pediátricos na Região Sul do Brasil no período de 2016

a 2020. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2022;37(4):438-44.

27. Carvalho B F. Análise dos óbitos de crianças internadas por

queimaduras no Hospital Infantil Joana de Gusmão no período de janeiro de 1991 a

março de 2019 [Trabalho de conclusão de curso]. Florianópolis: Universidade

Federal de Santa Catarina; 2019.

28. Favassa MT, Vietta GG, Nazário NO. Tendência temporal de internação

por queimadura no Sul do Brasil. Rev Bras Queimaduras.

2017;16(3):163-8.

29. http://tiny.cc/ anvisanotatecnica

1. Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina (UNISUL),

Campus Pedra Branca, Medicina, Palhoça, SC, Brazil

Corresponding author: Luzieli

Portaluppi Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina (UNISUL), Campus

Pedra Branca Av. Pedra Branca, 25, Palhoça, SC, Brazil. CEP: 88137-270 E-mail:

luzieliportaluppi@gmail.com

Article received: November 23, 2023.

Article accepted: April 30, 2024.

Conflicts of interest: none.