INTRODUCTION

In 1962, Thomas Cronin and Frank Gerow performed the first surgery to insert a

silicone breast prosthesis. Since then, with progressive growth, more than 1.5

million women undergo breast augmentation annually, whether for aesthetic

reasons or reconstruction1. In Brazil,

this procedure has seen a gradual increase over the last 25 years and, in 2011

alone, around 145 thousand Brazilian women underwent this surgery2, 3.

As a result, Brazil became the second largest market for breast implants in the

world, behind the United States2, 3, 4.

In 1997, Keech and Creech described the first case of breast implant-associated

anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL)5, 6, 7, 8, 9. However, it was recognized by the World

Health Organization (WHO) as an oncological entity only in 20165, 7,

8, 9. The incidence and prevalence of BIA-ALCL is extremely low, and in

2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) reported 573 cases in the United

States and worldwide, with 33 deaths resulting from this lymphoma6, 10.

The pathogenesis of BIA-ALCL is not fully understood, but it is described as a

process that involves multiple factors5,

6, 11. One of the theories found was that textured prostheses have

concavities, which results in a wider surface with greater texture. This

condition increases the likelihood of causing a chronic inflammatory response,

favoring the development of biofilm1,

5, 8, 11.

As a result of biofilm formation, a growth of gram-negative bacteria, Ralstonia

spp, was observed in the microbiome of the capsule of prostheses of patients

diagnosed with BIA-ALCL5, 12. Furthermore, the progression to

lymphoma occurs as a result of the malignant transformation of the T cells

involved, associated with the period of disease progression, the activation of

the immune response, and the patient’s genetics5.

BIA-ALCL constitutes a medical challenge that requires greater understanding and

attention, as the use of breast implants is growing exponentially throughout the

world, including in Brazil. And, consequently, the probability of new cases

tends to increase1. In this article, we

describe a case of a patient diagnosed with BIA-ALCL five years after breast

implant implementation.

CASE REPORT

Patient MSS, 54 years old, female, Caucasian, attends a consultation at a private

clinic complaining of post-pregnancy abdominal sagging and small breasts. A

patient with no previous history of cancer in the family. Previously performed

post-trauma splenectomy, epigastric herniorrhaphy, varicose veins, and two

cesarean sections. He has osteoarthritis in his fingers and uses simvastatin and

enalapril (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Pre-operative.

Figure 1 - Pre-operative.

On 12/02/2015, she underwent anchor abdominoplasty and breast augmentation, using

high-profile, textured silicone implants: 275cc on the right and 315cc on the

left (Figure 2). There were no

complications during or after surgery. Postoperative follow-up was carried out

until 2019 when he was discharged as an outpatient.

Figure 2 - Patient in 2019, with final result of surgery.

Figure 2 - Patient in 2019, with final result of surgery.

On 10/22/2020, she complained of progressive enlargement of her right breast

associated with local pain, with approximately one month of evolution. On

physical examination, there were no characteristic signs of capsular contracture

(Figure 3). Drainage of 200ml of

citrine yellow liquid was then performed, guided by ultrasound, with immediate

improvement in symptoms;

Figure 3 - On the left, patient being discharged from the outpatient clinic

(2019). On the right, in 2020, patient with right breast

enlargement.

Figure 3 - On the left, patient being discharged from the outpatient clinic

(2019). On the right, in 2020, patient with right breast

enlargement.

The material was sent for oncotic cytology. In the first laboratory, the cytology

was negative. Due to the senior author’s high suspicion of malignancy, the

sample was sent to a new laboratory. This time, positive oncotic cytology and

negative culture were found. The patient was immediately referred to the

oncologist.

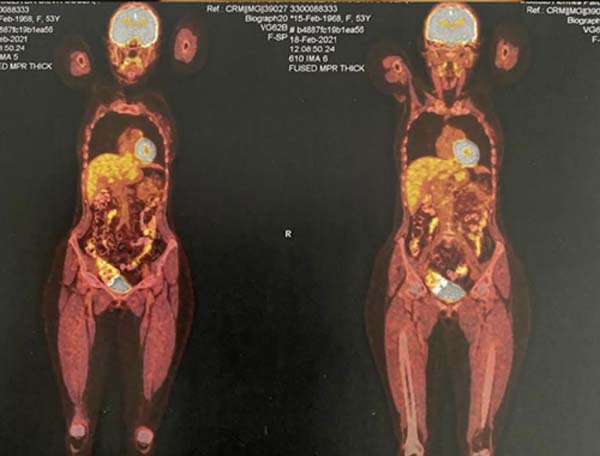

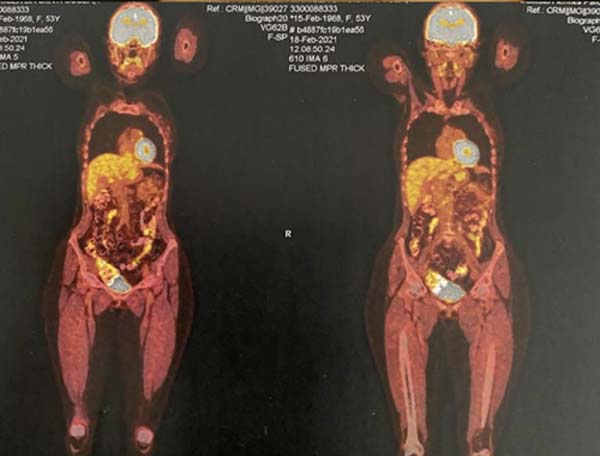

A PET-SCAN was performed, which showed areas of high uptake in the upper and

lower pole of the right breast, without lymph node involvement or distant

metastases (Figure 4).

The patient agreed to participate in the study and signed the Informed Consent

Form.

In December 2020, mastopexy was performed with explantation of the prostheses, as

well as extended resection of fat and adjacent muscle (Figure 5). During the surgical procedure, a usual

periprosthetic pseudocapsule was visualized in the right breast, with no signs

of malignancy (Figure 6).

Figure 5 - Prosthesis explantation - intraoperative.

Figure 5 - Prosthesis explantation - intraoperative.

Figure 6 - Breast prosthesis with pseudocapsule.

Figure 6 - Breast prosthesis with pseudocapsule.

The anatomopathological study confirmed a pseudocapsule infiltrated by bulky

anaplastic lymphoid cells, without extracapsular invasion. Immunohistochemistry

showed positive CD30, CD4, CD3, and TIA-1 markers and negative ALK-1 and CD20

markers. Therefore, it was confirmed that it was anaplastic large T-cell

lymphoma associated with a right breast implant, restricted to the

pseudocapsule.

Three months after the mastopexy with breast prosthesis explantation, a follow-up

PET-SCAN was performed, which did not reveal any further areas of

hypermetabolism in the patient’s right breast. Thus, the patient was free from

localized or distant disease. The patient reported that after the operation she

had pain in her breasts and bruises in the lower back, but that after a certain

time, they went away. Her breasts were different sizes and the post-surgical

scars bothered her, and despite this affecting her self-esteem, she was happy

with the medical treatment and medical attention throughout the process (Figures 7

8

9

10).

Figure 7 - Image demonstrating the immediate postoperative period.

Figure 7 - Image demonstrating the immediate postoperative period.

Figure 8 - Image demonstrating healing 3 months postoperatively.

Figure 8 - Image demonstrating healing 3 months postoperatively.

Figure 9 - PET-SCAN exam results.

Figure 9 - PET-SCAN exam results.

The main clinical manifestations of the disease are late seroma, breast

asymmetry, mass, and capsular contracture, with a higher frequency of the

former1. In the case reported, the

presence of a late and sudden seroma was the first change found.

Figure 10 - PET-SCAN exam results.

Figure 10 - PET-SCAN exam results.

DISCUSSION

Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma - BIA-ALCL is a rare

subtype of T-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, characterized as CD30 positive and ALK

negative5.

The disease is a rare condition that affects approximately one person in every

30,000 with breast implants. Polyurethane and textured implants are more

associated with the disease due to their greater surface area, which causes a

more intense chronic inflammatory reaction with immune activation mediated by

Th1 and Th17l· lymphocytes.

Explantation of the prosthesis with total capsulectomy may be sufficient to treat

BIA-ALCL, with resections extended to adjacent sites when necessary. However, in

some cases, adjuvant radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy is performed, for example,

if there is regional or distant metastasis1.

In this case, it was demonstrated that, for effective treatment, women with

sudden and late-onset seroma should undergo complementary tests for the earliest

possible diagnosis of this condition, even with a shorter development time than

the average, of around 10.6 years, as in this case, in which the disease

appeared within 5 years5. Among the

complementary tests that can be useful in the prognosis of the condition, we can

highlight the PET-SCAN, which highlights areas of hypermetabolism, corresponding

to cancer cells.

The importance of knowing the condition and having it in your range of diagnostic

hypotheses is necessary, even if the majority of late-appearing seromas are

benign. High suspicion as in the case portrayed, as it is a watershed in early

and late treatment, is essential for intervention at the right time and with

high cure rates.

CONCLUSION

Anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma is associated with breast implants and, despite

being a rare disease, should be suspected in post-breast augmentation patients

who present associated characteristic symptoms. It follows, therefore, that, for

an early diagnosis and effective treatment, women with a seroma that appears

suddenly and late must undergo additional tests to exclude this condition, even

with a shorter than average development time.

REFERENCES

1. Silva ACC, Pereira APA, Bicalho BC, Avelar CC, Abreu EDFA, Camarano

GCV et al. Linfoma anaplásico de grandes células associado a implante mamário:

uma revisão narrativa. Rev Eletr Acervo Saúde. 2020;12(11):e4767. Disponível em:

https://acervomais.com.br/index.php/saude/article/view/4767

2. Monteiro LL, Mangiavacchi W, Machado DG. A evolução das próteses

mamárias e os métodos de incisão utilizados em procedimentos de mamoplastia de

aumento. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2022;37(1):125-31.

3. Batista BN, Garicochea B, Aguilar VLN, Carvalho FM, Millan LS, Fraga

MFP, et al. Relato de caso de linfoma anaplásico de células grandes associado a

implante mamário em paciente brasileira. Rev Bras Cir Plást.

2017;32(3):445-9.

4. Veloso CN, Abbas K, Tonin JMF. Cirurgia plástica: qual o custo da

indústria da beleza? Anais do Congresso Brasileiro de Custos - ABC. Uberlândia:

XX Congresso Brasileiro de Custos; 2013. Disponível em: https://anaiscbc.emnuvens.com.br/anais/article/view/20

5. Real DSS, Resendes BS. Linfoma anaplásico de grandes células

relacionado ao implante mamário: revisão sistemática da literatura. Rev Bras Cir

Plást. 2019;34(4):531-8.

6. Lee JH. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma

(BIA-ALCL). Yeungnam Univ J Med. 2021;38(3):175-82.

7. Clemens MW Jacobsen ED, Horwitz SM. 2019 NCCN Consensus Guidelines

on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large

Cell Lymphoma (BIA-ALCL). Aesthet Surg J. 2019;39(Suppl_1):S3-S13. DOI:

10.1093/asj/sjy331

8. Berlin E, Singh K, Mills C, Shapira I, Bakst RL, Chadha M. Breast

Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma: Case Report and Review of the

Literature. Case Rep Hematol. 2018;2018:2414278. DOI:

10.1155/2018/2414278

9. Keech JA Jr, Creech BJ. Anaplastic T-cell lymphoma in proximity to a

saline-filled breast implant. Plast Reconstr Surg.

1997;100(2):554-5.

10. Pastorello RG, D’Almeida Costa F, Osório CABT, Makdissi FBA, Bezerra

SM, de Brot M, et al. Breast implant-associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma

in a Li-FRAUMENI patient: a case report. Diagn Pathol. 2018;13(1):10. DOI:

10.1186/s13000-018-0688-x

11. Loch-Wilkinson A, Beath KJ, Knight RJW, Wessels WLF, Magnusson M,

Papadopoulos T, et al. Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma

in Australia and New Zealand: High-Surface-Area Textured Implants Are Associated

with Increased Risk. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(4):645-54. DOI:

10.1097/PRS.0000000000003654

12. Johnson L, O’Donoghue JM, McLean N, Turton P, Khan AA, Turner SD, et

al. Breast implant associated anaplastic large cell lymphoma: The UK experience.

Recommendations on its management and implications for informed consent. Eur J

Surg Oncol. 2017;43(8):1393-401.

1. João XXIII Hospital, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

2. Baleia Hospital, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

3. José do Rosário Vellano University, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

4. Semper Hospital of Belo Horizonte, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil

Corresponding author: Antônio de Pádua Peppe

Neto Rodovia Papa João Paulo II, 4001, Edifício Gerais 13º and., Cidade Administrativa, Serra Verde, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. Zip Code: 31630-901.

E-mail: peppe-998@hotmail.com

Article received: November 20, 2023.

Article accepted: April 30, 2024.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Institution: Fundação Hospitalar do Estado de Minas Gerais (FHEMIG), Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.