INTRODUCTION

The oncological reconstruction of extensive areas in the head and neck requires the

plastic surgeon to make a difficult decision between the use of free flaps and pedicled

flaps. Free flaps are classically considered the gold standard treatment, but they

prolong surgical time, increasing procedure costs and postoperative recovery time.

Thus, pedicled flaps have re-emerged in recent years as an option to be considered

in elderly patients with advanced cancer and clinically weakened patients who benefit

from simpler reconstructive techniques1,2.

Among the pedicled flaps, we can use myocutaneous and fasciocutaneous flaps. The former

is usually the choice in deeper areas, which require soft tissue for filling3. On the other hand, fasciocutaneous flaps are excellent options for thinner coverage,

adaptable to the contour in the cervicofacial segment.

The supraclavicular flap has been increasingly used to reconstruct defects after head

and neck oncological resections. It is versatile, has a thin thickness and a similar

color to the region to be reconstructed. Furthermore, it has reliable vascularization

and is easy to dissect, making it reproducible in low-complexity services.

OBJECTIVE

To present a series of cases of supraclavicular flap, demonstrating the feasibility

of this surgery for oncological reconstruction in the head and neck in tumors of different

histological types and different stages.

METHODS

A retrospective study was carried out by collecting data from medical records of patients

admitted to the Instituto do Câncer of the State of São Paulo between December 2010

and March 2020. During this period, 62 patients underwent reconstruction with supraclavicular

flaps by the plastic surgery team for head and neck oncological reconstructions.

The Ethics Committee approved the study for Analysis of Research Projects of the Hospital

das Clínicas of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of São Paulo - HCFMUSP (CAAE

Number: 58900522.6.0000.0068).

The following information was collected: epidemiological data, comorbidities, histological

type and staging of the treated tumor, type of resection, defect area (calculated

by photographic analysis), pathological margins, neoadjuvant or adjuvant complementary

therapy, recurrence, and complications. The defect area was calculated by photographic

analysis using Adobe Photoshop® software.

RESULTS

Among the 62 patients reconstructed with a supraclavicular flap, 37 were male, and

25 were female. Fifty-eight patients (93.5%) had some associated comorbidity, the

most prevalent being systemic arterial hypertension (53.2%), smoking (53.2%), and

alcohol consumption (30.6%) (Table 1). The average age was 64.1 years, with a median of 65.5 years.

Table 1 - Patient characteristics.

|

|

Value/Percentage |

| Sex |

Feminine |

21 (41.1%) |

| Masculine |

30 (58.8%) |

| Comorbidities |

Systemic arterial hypertension |

26 (55.3%) |

| Smoking |

25 (53.2%) |

| Alcoholism |

18 (38.3%) |

| Diabetes mellitus |

15 (31.9%) |

| Dyslipidemia |

6 (12.8%) |

| Obesity |

5 (10.6%) |

| Histological type |

Squamous cell carcinoma |

36 (70.5%) |

| Sarcoma |

5 (9.8%) |

| Basal cell carcinoma |

5 (9.8%) |

| Salivary gland tumor |

4 (7.8%) |

| Neuroendocrine tumor |

1 (1.9%) |

| Free margins |

Yes |

37 (72.5%) |

| No |

13 (25.5%) |

| Unknown |

1 (1.9%) |

| Cervical emptying |

Selective |

26 (50.9%) |

| Radical |

7 (13.7%) |

| Unrealized |

18 (35.3%) |

| Neoadjuvance |

Yes |

2 (3.9%) |

| No |

49 (96%) |

| Adjuvance |

Yes |

30 (63.8%) |

| No |

21 (41.2%) |

Additional

reconstruction

|

Yes |

11 (21.6%) |

| No |

40 (78.4%) |

| Retail complications |

Yes |

27 (52.9%) |

| No |

24 (47%) |

Donor area

complications

|

Yes |

4 (7.8%) |

| No |

47 (92.2%) |

Table 1 - Patient characteristics.

The most prevalent histological type was squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck,

present in 45 cases (72.5%), 9 of which were in the larynx. Sarcoma (8%), basal cell

carcinoma of the skin (6%), salivary gland tumors (4%), neuroendocrine tumors (1.96%)

and melanoma (1.61%) were also treated.

Among squamous cell carcinomas (SCC), stages T2 (33.3%) and T3 (37.8%) were the most

prevalent. Only 4 cases of early tumor, T1 (8.9%), and 8 cases of locally advanced

tumor, T4 (17.8%), were included.

Clear margins were obtained in 48 resections (77.4%). In 13 patients, compromised

margins were maintained due to the morbidity of the required enlargement, but all

underwent adjuvant radiotherapy. There was also 1 case of unknown margin, as the resection

was performed in an external service without a record in the medical records. The

final area to be reconstructed was an average of 40.62 cm2, varying from 0.78cm2 (salivary fistula) to 137.15cm2.

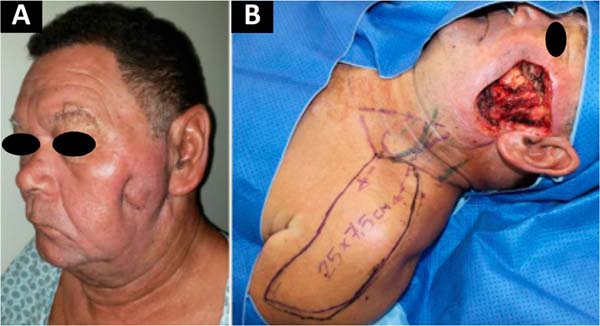

In Figure 1, we have a patient who underwent total parotidectomy extended to the skin due to

myxoid liposarcoma. In Figure 2, we see the same patient and his postoperative result of reconstruction with a pedicled

supraclavicular flap. In Figure 3, the same patient is during intraoperative planning.

Figure 1 - Preoperative (A). Intraoperatively, with demarcation of the supraclavicular flap,

based on the appropriate location of its pedicle, with a skin island measuring 25

x 7.5cm and an extension of the open area measuring 8 x 7.5cm after total parotidectomy

extended to the skin (B).

Figure 1 - Preoperative (A). Intraoperatively, with demarcation of the supraclavicular flap,

based on the appropriate location of its pedicle, with a skin island measuring 25

x 7.5cm and an extension of the open area measuring 8 x 7.5cm after total parotidectomy

extended to the skin (B).

Figure 2 - Postoperative result: frontal view (A) and profile (B) of the receptor area. Donor

area (C).

Figure 2 - Postoperative result: frontal view (A) and profile (B) of the receptor area. Donor

area (C).

Figure 3 - On the left, intraoperatively, demonstrating the positioning of the flap to cover

the defect. On the right, the immediate postoperative period after reconstruction

of the defect with a supraclavicular flap and primary closure of the donor area.

Figure 3 - On the left, intraoperatively, demonstrating the positioning of the flap to cover

the defect. On the right, the immediate postoperative period after reconstruction

of the defect with a supraclavicular flap and primary closure of the donor area.

Neck dissection was performed in 41 cases (66.1%), 32 of which were selective dissections

(51.6%), and 9 were modified radicals (14.5%). Twenty-one patients (33.9%) did not

undergo lymphadenectomy. Only three patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy before

the procedure. Adjuvant therapy was performed in 34 patients, 23 of whom received

exclusively radiotherapy and 11 chemoradiotherapy.

For full coverage of the area, some form of additional reconstruction, in addition

to the supraclavicular flap, was necessary in 13 patients (21%). The most used were

microsurgical fibula flap (4) and skin graft (3). Complementary reconstruction with

a microsurgical osteomyocutaneous fibula flap was performed in 4 cases, in addition

to a sural nerve graft for reconstruction of the facial nerve in 1 patient.

In total, 37 complications related to the flap (43.5%) were recorded, 16 of which

were partial necroses (25.8%), 11 dehiscences (17.7%), 5 total necrosis (8%), 3 salivary

fistulas (4.8%), 1 hematoma (1.6%) and 1 bleeding (1.6%). Reoperation was necessary

in 15 patients (29.4%), of which 9 were converted to another form of reconstruction.

In all cases, the donor area was closed primarily. Complications in the donor area

occurred in 4 patients, 3 of which were dehiscence and 1 seroma. All were treated

conservatively.

The average number of surgeries performed per patient until the reconstruction was

completed, including the treatment of complications and touch-ups, was 2.92.

The information is gathered in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Surgeries for head and neck reconstruction are still challenging for plastic surgery.

The professional who deals with this area must know how to combine function (speech,

facial expression, chewing, and breathing) with aesthetics, as it involves areas in

a region that determine appearance and self-esteem4.

Free flaps have gained great prominence and have established themselves as the choice

for covering extensive head and neck injuries. However, due to the prolonged surgical

time and the common profile of cancer patients - elderly, smoker, and with several

comorbidities - not every patient is a candidate for reconstruction with a microsurgical

flap2. Therefore, pedicled flaps remain an option. The benefits inherent to faster dissection

and transfer reduce morbidity related to prolonged general anesthesia and often eliminate

the need for intensive postoperative care1.

The supraclavicular flap is an axial flap based on supraclavicular branches of the

transverse cervical vessels, the first reports of which date back to the 19th century. Its use, however, was restricted due to the unreliability of its vascular

supply, explained by the lack of anatomical studies at the time when it was performed

randomly5.

In 1979, its axial vascularization pattern was initially described by Lamberty6. It was rediscovered as an excellent reconstructive option in 1997 by Pallua et al.3,7-9, being applied in the treatment of cervical retractions due to burns, and in 2009

by Chiu et al. as a reliable alternative in head and neck oncological reconstruction1.

It is a thin, flexible fasciocutaneous flap with skin with a texture similar to that

of the face, making it an ideal source of soft tissue for head and neck reconstructions10. In this way, it surpasses the results obtained with other regional flaps, such as

pectoralis major and trapezius, which are bulky and poorly adaptable to the contour

of the region1,2. It is a flap that allows the maintenance of facial expression and mobility of the

cervical region3. Currently, the angiosome of its pedicle is well described, based on recent studies

that demonstrate its vascular anatomy10.

The flap dissection technique was standardized and popularized by Pallua et al. in

19972. The flap must be quadrangular in shape; its pedicle must be found within the triangle

demarcated between the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, the clavicle,

and the external jugular vein; its size must be between 4 and 12cm wide and 20 to

30cm long7.

It is a versatile flap, capable of covering lesions located up to the limit between

the middle and distal third of the face. Its reach differentiates it from other pedicled

flaps in this region, such as the deltopectoral and pectoral flaps, since its rotation

point is more proximal, providing a more suitable arc of rotation for the cervicofacial

region. Furthermore, as it is hairless, it is suitable for reconstructions in the

oral cavity or the rest of the upper aerodigestive tract2.

In our series, eight pharyngeal reconstructions were performed with this flap. We

can also mention the possibility of tunneling the flap, which avoids a new approach

and reduces scarring in the donor area.

Adequate knowledge of the anatomy of the supraclavicular flap and the improvement

of its dissection technique allowed us to use it to reconstruct more extensive and

complex defects. In our service, the average area of the defect to be reconstructed

is relatively large (40.62cm2), larger than what had previously been described in the literature, demonstrating

the possibility of reconstructing larger defects with a relatively simple technique

with low morbidity.

The supraclavicular flap can be raised quickly, as its superficial pedicle ensures

that the entire dissection is restricted to the subfascial plane. Previous series

have demonstrated an average dissection time of 50 minutes2, which is advantageous in patients undergoing long-term oncological surgeries. The

donor area is usually closed primarily, without major sequelae3.

In the present study, we observed a relatively high rate of flap-related complications

(52.9%). However, some of these were minor complications, such as partial necrosis

or small dehiscence (44.4%), at rates similar to those found in the literature9. Two patients undergoing pharyngeal reconstruction presented salivary fistulas, which

were treated conservatively without compromising the final swallowing function. Further

studies to evaluate the main causes of complications related to the supraclavicular

flap should be carried out.

We must emphasize that although this flap is reliable, it still has its limitations.

It is not recommended for complex reconstructions resulting from extensive or deep

areas due to its smaller volume. It is also not applicable in cases of late reconstructions,

in which the integrity of the pedicle is uncertain.12 In these situations, free flaps still play a leading role. Even so, in this series,

we were able to successfully reconstruct 4 defects resulting from locally advanced

cancers (T4), and there are even studies that demonstrate its application in this

type of tumors2.

CONCLUSION

The supraclavicular flap plays an important role in oncological reconstructions of

the head and neck. Due to the reliability of its pedicle, shortened surgical time,

and low morbidity to the donor area, it should be considered as an option in patients

who are poor candidates for microsurgical flaps.

1. Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil

2. Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo, Divisão de Cirurgia Plástica, São Paulo,

SP, Brazil

Corresponding author: Giulia Godoy Takahashi Rua Arruda Alvim, 423, apto 51, Pinheiros, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, Zip Code: 05410-020,

E-mail: giu.godoy@gmail.com