INTRODUCTION

Since its introduction two decades ago1,2, negative

pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been established for its effectiveness in

managing acute and chronic wounds3-7. However, the

high technology makes the device complex to handle and expensive, reducing its

use in institutions with limited resources8. Trying to solve these problems, simplified vacuum

dressings systems (SVD)8-12 have been proposed since NPWT

does not necessarily require a special apparatus and can prepare wounds for

surgical treatment8,12-14. Despite using more basic mechanical and electrical

components, SVD retains essential safety attributes such as controlled suction

and wound sealing1,8,10,15,16.

Operational characteristics of SVD have been poorly evaluated and, occasionally,

seriously criticized3,16. Most of the studies available

do not have comparison groups and use limited methodologies, thus deserving

further evaluation8,10,11,15,17,18. The primary deficiencies are the use of rudimentary

materials, difficulty sealing wounds, and inability to maintain subatmospheric

pressures8,15,16,19. Deficiencies

result in accumulations of exudates, dressing changes, and repeated manipulation

of injuries. In addition to being boring, manipulations increase the risk of

aggravating injuries. In minor exudative wounds, inadequate seals can cause

perilesional air circulation, resulting in dryness, hemorrhage, and progressive

tissue necrosis1,19-21.

The decision to use a specific dressing should be guided not only by potential

efficacy, adverse effects, location, and symptoms of lesions (pain, exudate,

etc.) but also by the frequency of changes, clinical experience, patient

preference, and costs22-24. Even when economic value is

not an issue, the best treatment may be challenging to implement or unavailable,

so it is essential to know efficient second indication alternatives22.

OBJECTIVE

The study’s objective was to evaluate the feasibility (operational and financial)

of an SVD model (SVDM).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Feasibility study based on a randomized superiority clinical trial, blinded, with

two parallel arms, carried out between January 1, 2017, and May 1, 2020, Roberto

Santos Hospital (RSH; teaching hospital, multidisciplinary, 640 beds - Salvador,

Bahia - Brazil). The trial was registered in the Brazilian Registry of Clinical

Trials (RBR-5c8y6v) and followed CONSORT 2010 recommendations25. The research was approved by

the Research Ethics Council of the RSH (CAAE 55556816.7.0000.5028) and performed

following the Declaration of Helsinki. An Informed Consent Form was obtained

from the participating patients.

A sample of 50 patients was calculated using the R statistical software (R Core

Team, 2018), assuming a mean expected success rate of 98% for the SVDM group

and

72% for the control group, with a margin of superiority of 25%. A test power

of

80% and a significance level of 5% were assumed. Patients were admitted

sequentially in treatment (SVDM) and control groups (hydrofiber silver - SHF,

Aquacel Ag+ Extra™ - Convatec Inc., ER Squibb & Sons, North Carolina - USA)

following a list of random numbers performed in the statistical software R. The

statistical analysis used was by treatment protocol.

Adult patients hospitalized for acute (< 3 months) or chronic (≥ 3 months)

wounds were included in the study. Subjects with decompensated systemic

disorders (cardiac, thyroid, renal, pulmonary, hepatic, arterial hypertension,

severe anemia, severe malnutrition, and coagulopathies) were excluded. Painful

wounds, infected wounds, injuries associated with perilesional dermatoses,

allergic reactions, malignant neoplasms, and exposure to underlying exposed

vessels, nerves, or viscera were also not included. The emergence of serious

complications (e.g., hemorrhage, allergic reactions, sepsis, extensive necrosis,

severe pain), decompensation of previously controlled systemic disorders, and

deaths not attributable to the dressings were exclusion criteria used.

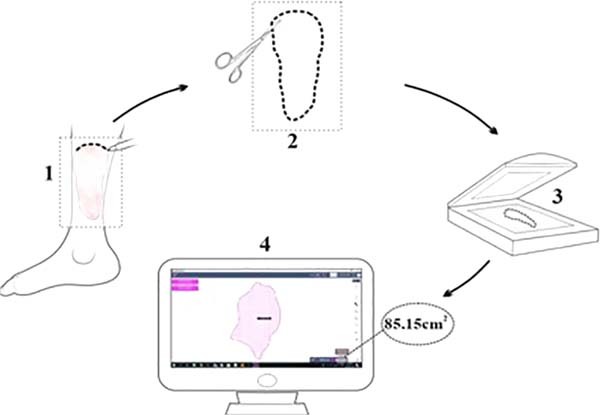

Wounded areas were obtained using the SketchandCalc app

(www.sketchandcalc.com - Figure 1). Application, SVDM, and clinical examples are shown in Figures 2 to 4. SVDM was regulated with a pressure of -125 mmHg. The first

dressing was used in continuous mode and the others in intermittent mode (5

minutes of vacuum and 2 minutes without vacuum)2,26.

Figure 1 - Measurement of wounded areas. 1: design of lesion contours using

transparent acetate film, 2: clipping of the demarcated area,

obtaining a two-dimensional pattern (template), 3: digitalization,

4: computerized measurement of the injured area.

Figure 1 - Measurement of wounded areas. 1: design of lesion contours using

transparent acetate film, 2: clipping of the demarcated area,

obtaining a two-dimensional pattern (template), 3: digitalization,

4: computerized measurement of the injured area.

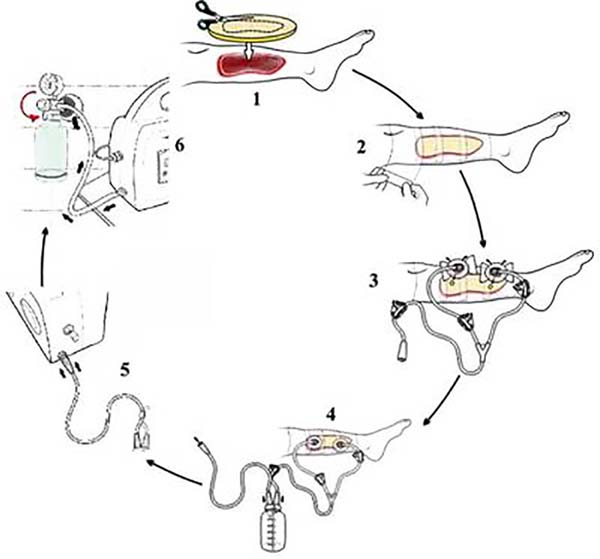

Figure 2 - Applying the SVDM. 1: cutting and placing the foam on the lesion,

2: sealing the foam using a transparent polyurethane adhesive film,

3: placing suction cups on one or two holes (2 cm) made in the film

on the foam, 4: suction tube connection to the liquid collection

canister, 5: connection of the canister to the control unit, 6:

activation of the NPWT and adjustment of the subatmospheric

pressure.

Figure 2 - Applying the SVDM. 1: cutting and placing the foam on the lesion,

2: sealing the foam using a transparent polyurethane adhesive film,

3: placing suction cups on one or two holes (2 cm) made in the film

on the foam, 4: suction tube connection to the liquid collection

canister, 5: connection of the canister to the control unit, 6:

activation of the NPWT and adjustment of the subatmospheric

pressure.

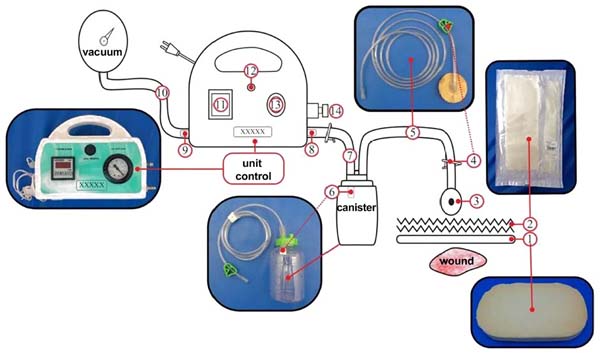

Figure 3 - SVDM setup. 1: foam, 2: adhesive film (polyurethane), 3: suction

cup, 4: clip cuts flow, 5: drainage tube, 6: filter, 7 and 10:

connecting tubes, 8: inlet and 9: air outlet, 11: timer display

(digital), 12: start button, 13: vacuum gauge display (pneumatic),

14: vacuum adjustment knob.

Figure 3 - SVDM setup. 1: foam, 2: adhesive film (polyurethane), 3: suction

cup, 4: clip cuts flow, 5: drainage tube, 6: filter, 7 and 10:

connecting tubes, 8: inlet and 9: air outlet, 11: timer display

(digital), 12: start button, 13: vacuum gauge display (pneumatic),

14: vacuum adjustment knob.

Figure 4 - Example of dressing results used in the management of

contaminated wounds. SVDM: (1) before and (2) after 10 days of

vacuum therapy, (3) SVDM installed; hydrofiber: (4) before and (5)

after 10 days of hydrofiber. Note shorter treatment time and

better-quality granulation tissue with the use of SVDM (cleaning,

development, and color).

Figure 4 - Example of dressing results used in the management of

contaminated wounds. SVDM: (1) before and (2) after 10 days of

vacuum therapy, (3) SVDM installed; hydrofiber: (4) before and (5)

after 10 days of hydrofiber. Note shorter treatment time and

better-quality granulation tissue with the use of SVDM (cleaning,

development, and color).

In both groups, debridements were performed to remove devitalized tissue

occasionally present. Changes were made at ≥ 50% saturation of dressings to

avoid unpleasant odor27.

Patients were followed for 14 days or until the granular lesion (≥ 75% of the

raw bed covered by healthy-looking granulation tissue).

The operational (ease of application and use) and financial feasibility (cost of

dressing changes) of the SVDM were evaluated. For operational feasibility,

outcomes analyzed were application time and amount of dressings; for financial

viability, total economic costs, and cost of dressing changes. Due to the

asymmetry of study variables, statistical analyses were performed using the

median, interquartile range, and bivariate standardized difference to compare

types of dressings.

Difference qualification criteria standardized were: [0-0.2]: absent; (0.2-0.5]:

small; (0.5-0.8]: moderate; [>0.8]: large (Cohen, 1988).

P-values calculated from the same test were adjusted for four

multiple comparisons under dependence conditions by the Benjamini &

Yekutieli method28. For cost

estimates adjusted for dressing application time, number of dressings, and

treatment time, the robust regression model was used with τ = 0.5

(median)29. An overall

α error of 0.05 was assumed for the entire study.

RESULTS

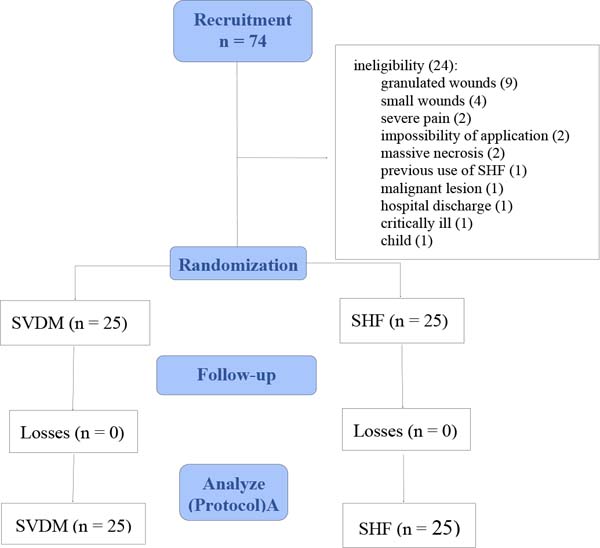

Of the 74 inpatients evaluated, 24 were excluded because they did not meet the

inclusion criteria (Figure 5). Patients

studied were mainly men (SVDM: 52% x SHF: 68%), mixed race (SVDM: 72% x SHF:

84%), non-obese (88%, both groups), and mean age in the age group 6th

decade (SVDM: 55 years x SHF: 50 years -Table 1). Adding the results of both groups, 270 dressings were applied in

589 days of treatment.

Table 1 - Demographic characterization of samples according to groups.

| Variable |

SVDM (n = 25) |

SHF

(n = 25)

|

| Mean (SD)

(CV%)

|

Min/Max |

Mean (SD)

(CV%)

|

Min/Max |

| Age (years) |

55 (14) (25) |

29/85 |

50 (16) (32) |

15/79 |

| Weight

(Kg) |

67 (16)

(23.9)

|

47/108 |

68 (15)

(21.8)

|

43/103 |

| Height (cm) |

164 (11) (6.9) |

145/184 |

166 (12) (6.9) |

154/180 |

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Sex |

|

|

|

|

| Men |

13 |

52 |

17 |

68 |

| Women |

12 |

48 |

8 |

32 |

| Ethnicity |

|

|

|

|

| Brown |

18 |

72 |

21 |

84 |

| Black |

5 |

20 |

2 |

8 |

| White |

2 |

8 |

2 |

8 |

| BMI |

|

|

|

|

| Low weight |

2 |

8 |

3 |

12 |

| Normal |

10 |

40 |

11 |

44 |

| Overweight |

10 |

40 |

8 |

32 |

| Obesity |

3 |

12 |

3 |

12 |

Table 1 - Demographic characterization of samples according to groups.

The median application time of the simplified dressing, in minutes, was about 6

times greater than that of SHF (22,7 min x 4,0 min; Sd=0.84;

p=0.0008). SVDM group showed a difference, for less, of 4 days

of treatment (3 days x 7 days; Sd=0.57; p=0.0028) and of 4

dressing changes (3 dressings x 7 dressings; Sd = 0.85;

p<0.0027) (Table 2).

Table 2 - Operational viability according to the type of dressing.

| Variable |

SVDM (n = 25) |

SHF

(n= 25)

|

| Md(IIQ R) |

Min/Max |

CVMd% |

Md(IIQR) |

Min/Max |

CVMd% |

Sd |

p* |

Installation time

of dressing

(min)

|

22.71 (10.0) |

16.5/38.7 |

44.0 |

4.0(3.0) |

2.2/10.4 |

75.6 |

0.84 |

0.0008 |

| Treatment time (days) |

10(5) |

3/15 |

50.0 |

14(0) |

7/15 |

0.0 |

0.57 |

0.0028 |

| Dressings/patient |

3(1) |

1/4 |

33.3 |

7(2) |

6/14 |

28.6 |

0.85 |

0.0027 |

Table 2 - Operational viability according to the type of dressing.

Table 3 (financial feasibility) presents

cost estimates adjusted for application time per dressing, number of dressings,

and treatment time using a robust regression model with τ = 0.5 (median). In

the

raw model (which only contains the type of dressing as an independent variable),

it is observed that the difference in predicted cost of SVDM to SHF was only

US$

5.88. However, when adding other variables mentioned (covariates), the

difference became US$ 209.99 (adjusted model 1). There was, therefore, a

significant change when considering all covariates; thus, the crude model proved

unsatisfactory for predicting the median cost difference between dressings.

Table 3 - Estimating median cost adjusted by dressing application time, number

of dressings, and treatment time using robust regression with τ = 0.5

(median).

| Variable |

Gross

model

|

Adjusted

model 1

|

Adjusted

model 2

|

Saturated

model

|

Final adjusted model |

| Cost (R$) |

pB |

Cost (R$) |

pAj1 |

VIF |

Cost (R$) |

pAj2 |

Cost (R$) |

pS |

Cost (R$) |

pAjf |

| Intercept (β0) |

931.26 |

<

0.0001

|

-1139.05 |

< 0.0001 |

- |

-1269.37 |

< 0.0001 |

-894.75 |

0.1960 |

-1270.55 |

< 0.0001 |

| SVDM

(β1)

|

-31.19 |

0.8470 |

1112.96 |

0.0001 |

2.10 |

1275.15 |

<

0.0001

|

890.53 |

0.1978 |

1282.82 |

<

0.0001

|

| Installation time per dressing (min)

(β2)

|

- |

- |

0.74 |

0.7080 |

2.52 |

0.31 |

0.9138 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| Number of

dressings (β3)

|

- |

- |

246.00 |

0.0017 |

55.89 |

297.17 |

<

0.0001

|

245.92 |

0.0137 |

297.48 |

<

0.0001

|

| Treatment time (days) (β4)

|

- |

- |

17.03 |

0.4032 |

47.72 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

SVDM

(β1) x

Number of dressings

(β3)

|

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

58.20 |

0.5462 |

- |

- |

Table 3 - Estimating median cost adjusted by dressing application time, number

of dressings, and treatment time using robust regression with τ = 0.5

(median).

Adjusted model 1 showed a strong correlation (multicollinearity) between the

number of dressings and the treatment

time, with variance inflation factor (VIF) values greater than

ten31. Therefore,

these covariates cannot remain together in the model to avoid bias. As the

number of dressings was the covariate that showed the most

remarkable difference in cost, the covariate, the treatment

time was excluded from the model.

In adjusted model 2, the application time covariate did not

contribute to the predicted cost (US$ 0.31; p = 0.9138), being

removed from the model.

In adjusted model 2, covariates that contributed to median cost estimates were

the type of dressing and the number of dressings. However, their probable

absence was evidenced after evaluating the interaction between these covariates

in a saturated model with an interaction term (p=0.5462).

The final adjusted model shows that the estimated cost difference between SVDM

and SHF was US$ 242.04 (p<0.0001). In other words, costs

would be much higher for SVDM if the group required the same number of dressings

as SHF. Since more SHF dressings were changed (SHF: 7 x SVDM: 3), both the cost

difference found directly in the study (continuous lines) and the difference

if

the groups had the same number of dressings (dashed line) were represented in

Figure 6.

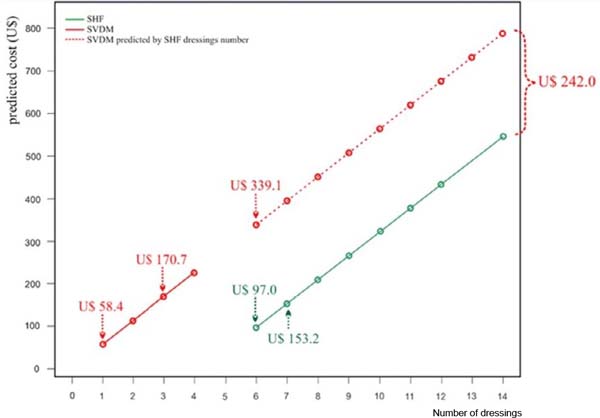

Figure 6 - Predicted cost based on a robust regression model with τ = 0.5

(median) as a function of the number of dressings according to the

type of dressing.

Figure 6 - Predicted cost based on a robust regression model with τ = 0.5

(median) as a function of the number of dressings according to the

type of dressing.

The figure shows, for example, that the estimated costs for six dressings

(minimum number of dressings performed in the SHF group) were: SVDM: US$ 339.09

x SHF: US$ 97.04; estimated costs for the median number of dressings served in

each group were SVDM (3 dressings): US$ 170.70 x SHF (7 dressings): US$ 153.17

(i.e., US$ 17.53 more per patient); finally, the estimated cost for 1 SVDM was

US$ 58.44, which corresponds to an estimated price for 5.31 SHF. Therefore, the

SVDM estimated cost was higher than the SHF estimated cost in all items

evaluated.

DISCUSSION

SVD reduces technological resources to facilitate handling and minimize costs.

However, simplification must not compromise product reliability8,11,16. To ensure

safety, it is recommended that any NPTW equipment has suction control mechanisms

to avoid extreme variations in subatmospheric pressure and, in cases of intense

pressure, to prevent exsanguination through treated wounds3.

SVDM, in addition to containing these safety elements, including a pneumatic

pressure gauge, was equipped with a small specialized filter (high molecular

weight polyethylene - Figure 3) that

becomes impervious when coming into contact with exudates, ensuring blockage

of

effluxes beyond the liquid collection canister. Finally, light-colored foams

were used to facilitate observation of their degree of saturation and retention

of debris. Conventional NPWT uses black foams, which makes this observation

impossible. The transparency of a dressing allows continuous monitoring of wound

beds and perilesional skin without violating the dressing, reducing changes and

costs32.

Few data are available on handling vacuum dressings, making satisfactory

discussions difficult. In a systematic review, the application method was

briefly described without illustrations26. In line with the current monograph, a comparative

study of chronic wound treatment using a wall suction SVD also reported six

steps for applying the vacuum dressing13. Except for these papers and what is recorded in the

conventional NPWT manufacturing manual, descriptions of placement steps have

not

been made in reviews on the subject3,4,33.

The longer application time SVDM (22.7 min x 3.98 min) was attributed to the

greater complexity of using the device and, therefore, the need for training

to

master the procedure. The complexity was due to the multiple steps required for

placement of the SVDM (6 steps x 2 steps), the increased care needed for sealing

dressings (Figure 2, step 2), and the extra

time required to remove foams adhered to wounds.

Only one randomized trial using an SVD model (also powered by the hospital

vacuum) provided results in the references consulted, with an average

application time of 19 min34.

Compared with the present study, the difference of just under four minutes for

dressing changes (22.71 min x 19 min) was considered clinically unimportant.

The

data suggests that the application complexity of the SVDM may be similar to that

of other simplified dressing models.

Application complexity is also a problem related to conventional NPWT1,3,6, especially in

wounds located in contoured areas (e.g., neck, hands, and feet), in places with

recesses (e.g., between fingers, intergluteal crease), in regions that have

natural orifices (e.g., perineum) or when perilesional skin is continuously

moist (dermatoses, dermabrasions, burns, avulsions, among other

conditions)1,3,6,13,35. The complexity is so

significant that conventional NPWT is performed by highly trained nursing teams

who do not work in the hospital that hires them, making it difficult for this

team to access, especially at night, on weekends, in intensive care units, and

operating rooms. Furthermore, obtaining and maintaining wound seals can be a

frustrating exercise, further diminishing the popularity of vacuum

dressings36. In

contrast, occlusive dressings such as SHF are simple, direct, and quick to

apply24. Finally, NPWT

requires the additional work of daily face-to-face monitoring to prevent

leaks13,14.

The SVDM maintained wound seals, controlled subatmospheric pressure, and drained

exudates without early exchanges. As a result, maintenance of the SVDM (3 days)

was similar to that described for most of both standard NPWT or other SVD (2

to

3 days)6,14,37.

Vacuum dressings can be fully functional until ten days if the adhesive film

is

kept intact13,38. There was a reduction in the number of

dressings in the SVDM group (3 x 7), attributed to the continuous drainage of

fluids, which kept dressings unsaturated and operating longer8. Foams used in NPWT, thanks to

their absorbent properties, allow fewer exchanges. To avoid making them smelly

or adhesive, the dressings should be changed every two to three days39,40.

Accumulation of liquid during intermittency can break the film and result in

leaks; consequently, intermittent NPWT has been replaced by a “variable NPWT,”

characterized by a smooth cycle of variation between less intense pressures (-80

mmHg and -10mmHg) to maintain a continuous subatmospheric environment41,42. SVD powered by wall suction, such as the SVDM, may be

desirable, as pressure variations in the hospital network (which are transmitted

to the equipment) mimic the effects of variable NPWT.

Costs analysis is challenging, as available data are poor26 and, contrary to what was

performed in the present trial, described without adjustments for covariates.

SVDM costs depended on the average selling price (SVDM unit: US$ 56.6 x SHF unit

15 cm x 15 cm: US$ 20.5), the number of changes, and the type of dressing.

Results indicate that SVDM implies increased costs per patient (US$ 17.5 more)

and per dressing change, with a single SVDM change (US$ 58.5) equivalent to the

approximate cost of 5 SHF changes. However, four dressings are saved when opting

for SVDM. Suppose the number of SVDM exchanges is similar to that of SHF

exchanges; the cost difference increases (US$ 242.0 - Table 3, Figure 6).

Therefore, care to ensure operational quality is essential so that the median

number of SVDM dressing changes is not exceeded (three shifts); otherwise, the

result would be a considerable increase in the final cost.

Direct costs obtained for SVDM appear much lower than for standard NPWT. The cost

of conventional NPWT was estimated to range from US$ 1,750.0 to US$ 3,450.0

weekly and US$ 1,286.0 to US$ 5,452.0 per patient10,12,26,43. In children, the monthly cost of vacuum therapy was

recently estimated at US$ 1,677/patient44. Treatment can become up to 20 times cheaper with

simplified dressings systems than conventional NPWT10,45. SVD

costs can be as low as US$ 6.4/dressing39, US$ 15.0/day14, or 2% of the average cost of using the VAC

System12.

One reason for lower costs is that hospital vacuum systems, dispensing

specialized devices10, supply

SVD. Another reason is using simple, lower-cost, locally manufactured materials

(foams, polyurethane films, canisters, tubes made of PVC plastic,

etc.)11. Finally, the

current study showed that the cost of SVDM can become even lower if the number

of dressings per patient is minimized. The reduction in exchanges is possible,

as fully functioning NPWT dressings for up to ten days have been

described13,38.

CONCLUSION

SVDM proved greater operational complexity and cost, but it can be feasible as

long professionals for the application master the procedure and there are no

more than three dressing changes per patient.

1. Universidade Federal da Bahia, Salvador, BA,

Brazil

2. Secretaria de Saúde do Estado da Bahia,

Salvador, BA, Brazil

Corresponding author: Sandro Cilindro de Souza Av.

Reitor Miguel Calmon, sala 110, 1º andar, Vale do Canela, Salvador, BA, Brazil.,

Zip Code: 40110-902, E-mail: sandrocilin@gmail.com