INTRODUCTION

Necrotizing fasciitis has high mortality rates when diagnosis and treatment do not

occur early, particularly in patients with diabetes mellitus and immunosuppression,

which are the main risk factors1-3. Necrotizing fasciitis resulting from Fournier’s gangrene is characterized by ischemia

and thrombosis of the subcutaneous vessels of the scrotal region, resulting in necrosis4-6, which requires debridement7-9 as soon as the diagnosis is established. Point of care ultrasound has been used successfully

in intensive care.

OBJECTIVE

The study’s objectives are to present the application of point-of-care ultrasound

in early diagnosis and the relevance of anatomy in necrotizing fasciitis from Fournier’s

gangrene.

METHODS

The application of point-of-care ultrasound in early diagnosis and the relevance of

anatomy in necrotizing fasciitis were studied, through a careful evaluation of the

literature, including scientific articles based on PubMed, VHL, SciELO and Lilacs

databases, as well as books established in the literature. The descriptors used were:

Fasciitis Necrotizing, Anatomy, Ultrasound, Surgery and Plastic Surgery.

RESULTS

Application of point of care ultrasound in the early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis

The application of ultrasound in necrotizing fasciitis consisted of using acoustic

window concepts to visualize the presence of thickening of the affected fascia associated

with gases, which may be present in the first 48 hours of necrotizing fasciitis evolution.

The use of ultrasound enabled the early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis, followed

by initiation of antibiotic therapy and surgical treatment, with a consequent reduction

in mortality. (Figure 1).

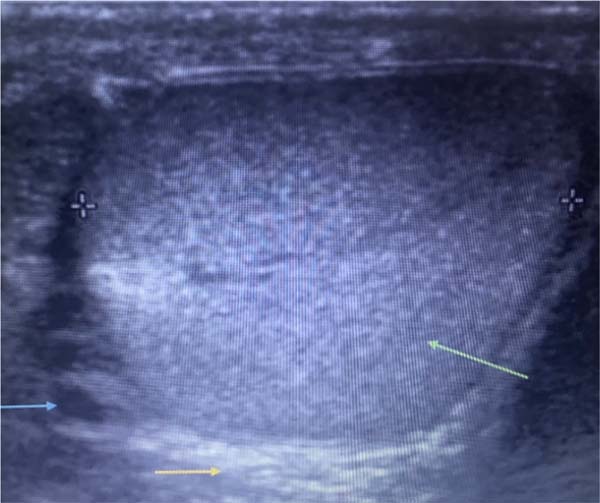

Figure 1 - Testicular ultrasound image showing normal testis (green arrow), thickening of the

dartos layer (yellow arrow) and gas (blue arrow).

Figure 1 - Testicular ultrasound image showing normal testis (green arrow), thickening of the

dartos layer (yellow arrow) and gas (blue arrow).

Relevance of anatomy in Fournier’s gangrene

The Colles, Buck, dartos, and Scarpa fascial lining layers represented respectively

anatomical communications between the fascial lining layers of the perineal, scrotal,

penile, and abdominal regions that contribute to the rapid spread of infection in

Fournier’s gangrene necrotizing fasciitis. Communication between Buck’s scrotal lining

layer and Scarpa’s lamellar layer in the abdomen occurred through continuity with

the fascial lining layer of the inguinal region.

DISCUSSION

The infectious process of necrotizing fasciitis resulting from Fournier’s gangrene

spreads through the continuity of the fasciae, hence the importance of anatomy. The

scrotum, a cutaneous pouch that contains the testes and lower parts of the spermatic

cord, is made up of two layers, one of skin, superficially, and the other of a thin

layer, the dartos, which, anatomically, consists of a layer of smooth muscle, located

under the skin of the scrotum. In women, this musculature is less developed and is

called dartos mulierbris, being under the skin of the labia majora3,4.

Dartos communicates with the superficial muscular fascia of the perineum called Colles’

fascia, which lines the muscles of the superficial portion of the perineum. The fascia

that lines the cavernous bodies of the penis is called Buck’s fascia. Colles’ fascia

of the perineum has anatomical continuity with Scarpa’s fascia, the deep layer of

the abdominal wall lining4,5. The important communication between Colles’ fascia, dartos, Buck’s fascia and Scarpa’s

fascia is responsible for the rapid spread of the infectious process initiated in

the perineal-scrotal region to the penis and the abdominal wall in the most severe

cases.

The delay in defining the diagnosis, late initiation of treatment6,8, diabetes mellitus and immunosuppression6-8 were conditions related to increased mortality in Fournier’s gangrene. Imaging methods,

such as ultrasound and computed tomography, are important diagnostic aids9,10. The pathophysiology of Fournier’s necrotizing fasciitis is characterized by vessel

ischemia and thrombosis, resulting in fascial necrosis11,12. After ischemia and thrombosis, bacteria spread, and the anaerobic gas-producing

bacteria are responsible for the crepitus found in the first 48 hours of infection13, which can develop under the apparently normal skin14,15.

The most prevalent microorganisms are Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacteroides

fragilis and Streptococcus fecalis13-17. Reducing the mortality rate depends on early diagnosis and rapid initiation of treatments

with broad-spectrum antibiotics18-21, debridement of necrotic tissues1,22-24 and the association of hyperbaric therapy25-29. The application of ultrasound has shown great growth today, especially in anesthesia

and intensive care. In anesthesia, ultrasound has helped to locate nerves during peripheral

blocks. In intensive care medicine and trauma, ultrasound is highlighted in diagnosing

pleural effusion, pneumothorax and cardiac alterations during cardiogenic shock30-32. In the present study, the application of ultrasound was important in the early diagnosis

of necrotizing fasciitis, enabling the rapid initiation of treatment.

CONCLUSION

Anatomical communications between the lining layers of the perineum, scrotum, penis,

inguinal, and abdomen regions contribute to the progression of infection in Fournier’s

gangrene necrotizing fasciitis. The application of ultrasound allowed the early diagnosis

of infection in necrotizing fasciitis, allowing the rapid initiation of treatment

with antibiotic therapy and surgical treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Fernandez-Alcaraz DA, Guillén-Lozoya AH, Uribe-Montoya J, Romero-Mata R, Gutierrez-González

A. Etiology of Fournier gangrene as a prognostic factor in mortality: Analysis of

121 cases. Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed). 2019;43(10):557-61.

2. Montrief T, Long B, Koyfman A, Auerbach J. Fournier Gangrene: A Review for Emergency

Clinicians. J Emerg Med. 2019;57(4):488-500.

3. Fattini CA, Dângelo JG. Anatomia humana sistêmica e segmentar. 3ª ed. São Paulo: Atheneu;

2011. 780 p.

4. Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AMR. Anatomia orientada para a clínica. 8ª ed. Rio de Janeiro:

Guanabara-Koogan; 2019. 1128 p.

5. Netter FH. Atlas de anatomia humana 3D. 6ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier; 2015. 640

p.

6. Singh A, Ahmed K, Aydin A, Khan MS, Dasgupta P. Fournier’s gangrene. A clinical review.

Arch Ital Urol Androl. 2016;88(3):157-64

7. Short B. Fournier gangrene: an historical reappraisal. Intern Med J. 2018;48(9):1157-

60.

8. Norton KS, Johnson LW, Perry T, Perry KH, Sehon JK, Zibari GB. Management of Fournier’s

gangrene: an eleven year retrospective analysis of early recognition, diagnosis, and

treatment. Am Surg. 2002;68(8):709-13.

9. Kuchinka J, Matykiewicz J, Wawrzycka I, Kot M, Karcz W, Głuszek S. Fournier’s gangrene

- challenge for surgeon. Pol Przegl Chir. 2019;92(5):1-5.

10. Eke N. Fournier’s gangrene: a review of 1726 cases. Br J Surg. 2000;87(6):718-28.

11. Arora A, Rege S, Surpam S, Gothwal K, Narwade A. Predicting Mortality in Fournier

Gangrene and Validating the Fournier Gangrene Severity Index: Our Experience with

50 Patients in a Tertiary Care Center in India. Urol Int. 2019;102(3):311-8.

12. Abass-Shereef J, Kovacs M, Simon EL. Fournier’s Gangrene Masking as Perineal and Scrotal

Cellulitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(9):1719.e1-1719.e2.

13. Ballard DH, Mazaheri P, Raptis CA, Lubner MG, Menias CO, Pickhardt PJ, et al. Fournier

Gangrene in Men and Women: Appearance on CT, Ultrasound, and MRI and What the Surgeon

Wants to Know. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2020;71(1):30-9.

14. Levenson RB, Singh AK, Novelline RA. Fournier gangrene: role of imaging. Radiographics.

2008;28(2):519-28.

15. Yilmazlar T, Gulcu B, Isik O, Ozturk E. Microbiological aspects of Fournier’s gangrene.

Int J Surg. 2017;40(1):135-8.

16. Kuo CF, Wang WS, Lee CM, Liu CP, Tseng HK. Fournier’s gangrene: ten-year experience

in a medical center in northern Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40(6):500-6.

17. Cardoso JB, Féres O. Gangrena de Fournier. Medicina (Ribeirão Preto). 2007;40(4):493-9.

18. Kuzaka B, Wróblewska MM, Borkowski T, Kawecki D, Kuzaka P, Młynarczyk G, et al. Fournier’s

Gangrene: Clinical Presentation of 13 Cases. Med Sci Monit. 2018;24:548-55.

19. Demir CY, Yuzkat N, Ozsular Y, Kocak OF, Soyalp C, Demirkiran H. Fournier Gangrene:

Association of Mortality with the Complete Blood Count Parameters. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 2018 Jul;142(1):68e-75e.

20. Lin TY, Cheng IH, Ou CH, Tsai YS, Tong YC, Cheng HL, et al. Incorporating Simplified

Fournier’s Gangrene Severity Index with early surgical intervention can maximize survival

in high-risk Fournier’s gangrene patients. Int J Urol. 2019 Jul;26(7):737-43.

21. Radcliffe RS, Khan MA. Mortality associated with Fournier’s gangrene remains unchanged

over 25 years. BJU Int. 2020;125(4):610-6.

22. Carrillo-Córdova LD, Aguilar-Aizcorbe S, Hernández-Farías MA, Acevedo-García C, Soria-Fernández

G, Garduño-Arteaga ML. Escherichia coli productora de betalactamasas de espectro extendido

como agente causal de gangrena de Fournier de origen urogenital asociada a mayor mortalidade.

Cir Cir. 2018;86(4):327-31.

23. Syllaios A, Davakis S, Karydakis L, Vailas M, Garmpis N, Mpaili E, et al. Treatment

of Fournier’s Gangrene With Vacuum-assisted Closure Therapy as Enhanced Recovery Treatment

Modality. In Vivo. 2020;34(3):1499-502.

24. Egin S, Kamali S, Hot S, Gökçek B, Yesiltas M. Comparison of Mortality in Fournier’s

Gangrene with the Two Scoring Systems. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2020;30(1):67-72.

25. Mindrup SR, Kealey GP, Fallon B. Hyperbaric oxygen for the treatment of fournier’s

gangrene. J Urol. 2005;173(6):1975-7.

26. Li C, Zhou X, Liu LF, Qi F, Chen JB, Zu XB. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy as an Adjuvant

Therapy for Comprehensive Treatment of Fournier’s Gangrene. Urol Int. 2015;94(4):453-8.

27. Chavez Zenteno R, Cutipa Aquino NA, Lafuente Zapata FM, Manya Tacusi LK, Lara Torrico

A. Impacto de la enfermedad de Fournier en pacientes del Hospital Clínico Viedma durante

enero del 2008 a marzo del 2013. Rev Cientif Cienc Med. 2013;6(1):17-9.

28. Ramírez Cabezas F, Ramírez Orjuela JG. Incidencia, factores de riesgo, mortalidad

y protocolo de tratamiento quirúrgico de la gangrena de Fournier, hospital Luis Vernaza,

período 2003 - 2008. Medicina (Guayaquil). 2011;16(3):183-8.

29. Martins ACL, Ribeiro BER, Silva DC, Santos LV, Fófano GA. A utilização do ultrassom

point of care no atendimento aos pacientes na urgência e emergência: Revisão da literatura.

Braz J Surg Clin Res. 2021;36(1):78-86.

30. Kameda T, Kimura A. Basic point-of-care ultrasound framework based on the airway,

breathing, and circulation approach for the initial management of shock and dyspnea.

Acute Med Surg. 2020 Jan 20;7(1):e481.

31. Fischer BG, Baduashvili A. Cardiac Point-of-Care Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Infective

Endocarditis in a Patient with Non-Specific Rheumatologic Symptoms and Glomerulonephritis.

Am J Case Rep. 2019 Apr 18;20:542-7.

32. Van Schaik GWW, Van Schaik KD, Murphy MC. Point-of-Care Ultrasonography (POCUS) in

a Community Emergency Department: An Analysis of Decision Making and Cost Savings

Associated With POCUS. J Ultrasound Med. 2019 Aug;38(8):2133-40.

1. Faculty of Medicine, Federal University of Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Rui Lopes Filho, Rua Cônego Rocha Franco, nº 133, Bairro Gutierrez, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil, Zip

Code 30441-045, E-mail: ruilopesfilho@terra.com.brw

Article received: June 15, 2020.

Article accepted: December 13, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none.