INTRODUCTION

In cases of cleft lip and palate (CLP), palatoplasty aims at the morphological and

functional restoration of the palate, establishing a functional velopharyngeal mechanism

for speech, swallowing and hearing, preserving the growth potential of the middle

third of the face1,2,2. Post-palatoplasty complications may include hemorrhage, difficulty breathing, patch

necrosis, repair dehiscence. The occurrence of oronasal fistula (ONF) and velopharyngeal

dysfunction (VDP) is the most challenging interdisciplinary team complication. ONF

may result from tension in the surgical repair of the palate, and its healing is accompanied

by fibrosis compromising tissue vascularization. The healing process, therefore, produces

retractions with morphological and functional consequences. The occurrence of ONF

is associated with speech impairments, nasal reflux, halitosis and chronic infections,

being an indicator of surgical success or failure3-8.

The magnitude of the occurrence of ONF is not fully known, and there are divergences

regarding the indexes reported in the literature ranging from 0%9-11 to 78%12. The variation in ONF occurrence results from the lack of standardization of evaluation

protocols and a definition of what should be considered fistula13,14. Papers on ONF of scientific relevance were published, including meta-analyses14, systematic reviews7,15 and systematic scope reviews16. However, most studies do not control variables that affect the occurrence of ONF,

do not describe in detail the surgical techniques of primary palatoplasty, nor do

they measure the amplitude of the cleft before surgery4,7,8,14,16,17. The lack of reports on criteria for the inclusion and exclusion of ONF in published

studies is also an impact factor on the percentage of occurrence of these complications

since some studies exclude fistulas before the incisor foramen or intentionally not

repaired fistulas2,13,18-23.

Understanding the importance and complexity of the identification of ONF, some classification

systems addressed both the standardization of the nomenclature13,18,24 and the surgical management of these occurrences24,25. These publications reflect the concern about the resolution of ONF seeking to favor

the prevention and treatment of these complications. A study involving data analysis

recorded in medical records of 466 patients with a unilateral transforaminal cleft,

Jacob et al. (2020)26 reported both variabilities in terminology and a lack of consensus between the areas

of plastic surgery and speech therapy regarding the occurrence of ONF. They were observed

by Jacob et al. (2020)26: absent or incomplete records in medical records, inadequate photographic images

for the identification of ONF and divergences regarding the inclusion of fistulas

in the preforaminal incisive region as surgical complications. The authors indicated

the need for a comprehensive fistula classification system, which can be used effectively

by multidisciplinary teams, optimizing the systematic documentation of the results

of the treatment of FLP26.

OBJECTIVE

The present study aimed to develop a protocol for the classification of palate fistula

based on morphological, embryological and symptomatology criteria of the fistula.

METHODS

This study was conducted at the Craniofacial Anomalies Rehabilitation Hospital of

the University of São Paulo (HRAC-USP), from 2013 to 2017, after approval by the Institution’s

Ethics Committee (protocol no. 3.305124).

The development of the protocol occurred after the survey of 466 medical records of

a randomized clinical trial involving patients with unilateral complete cleft lip

and palate and 13,876 photographic images of patients of the institution, analyzing

the presence and location of the ONF, reported by the areas of plastic surgery and

speech therapy. The survey indicated the use of distinct terminology between the areas,

failure to document the occurrences (incomplete or absent data), and inadequate photographic

images for ONF classification. Considering the difficulties encountered, the planning

for the construction of this protocol included the following steps: 1) to standardize

the definition of ONF; 2) define the anatomical references; 3) establish embryological

and morphological criteria; 4) include the symptomatology; and 5) establish criteria

for photographic imaging.

Brosco-Dutka classification system

Definition of ONF

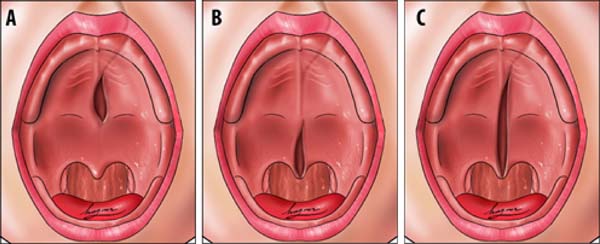

In this protocol, we defined a fistula as a failure to heal or rupture in the primary

surgical repair of the palate, according to Cohen et al. (1991) 18 and Muzaffar et

al. (2001) 27. Palate dehiscence was defined as the rupture of the surgical closure

of an entire morphological region of the palate and classified using the same protocol

(Figure 1). It is also postulated that all fistulas should be reported, including punctate

fistulas (micro-fistulas), asymptomatic fistulas, and fistulas left intentionally.

Figure 1 - A. Dehiscence of hard palate; B. Soft palate dehiscence; C. Hard and soft palate dehiscence.

Figure 1 - A. Dehiscence of hard palate; B. Soft palate dehiscence; C. Hard and soft palate dehiscence.

Anatomical references

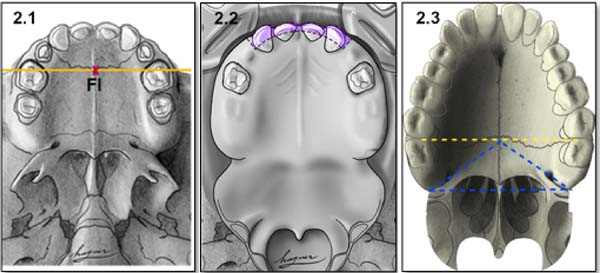

Anatomical references include incisive foramen, upper alveolar arch, and the transition

area between the hard palate and soft palate (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Anatomical references of the protocol: 2.1. Incisive foramen (FI); 2.2. Alveolar arch;

2.3. Transition area between hard palate and soft palate.

Figure 2 - Anatomical references of the protocol: 2.1. Incisive foramen (FI); 2.2. Alveolar arch;

2.3. Transition area between hard palate and soft palate.

Incisor foramen (FI)

The FI is a demarcatory anatomical point that fragments the primary palate from the

secondary palate; however, in patients with FLP, it is nonexistent due to the absence

of bone at the cleft site24. Defining the transition point between the primary and secondary palate in patients

with a history of FLP is a complex task, hampered by morphological changes inherent

to the fissure and resulting from the fibrosis process associated with post-surgical

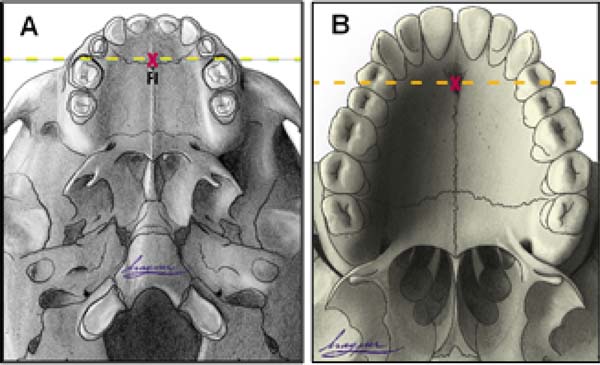

healing. To favor this process, the Brosco-Dutka protocol establishes the incisive

line as an imaginary line drawn between the points of contact between the canine teeth

and the 1st deciduous molar in the child (Figure 3A). In adults, this line is drawn between the point of contact between the canines

and the 1st premolar (Figure 3B). When considering the analysis of photographic images for the definition of FI,

it is fundamental to standardize to obtain intraoral images. Photographic documentation

must be obtained with the use of mirrors for photography by a trained professional.

Figure 3 - Illustration of the imaginary line tracings for identification of the incisive foramen:

A. In the child; B. In adulthood.

Figure 3 - Illustration of the imaginary line tracings for identification of the incisive foramen:

A. In the child; B. In adulthood.

Upper alveolar arch

The upper alveolar arch is the portion of the maxilla that lines the dental alveoli,

being an important anatomical reference for identifying pre-alveolar fistulas and

fistulas of the alveolar arch, which are those located in the region of the labial

vestibule and the alveolar arch itself. The terminology “vestibular fistulas” or “oronasal

fistulas” should not be used in this classification.

Transition area between the hard palate and soft palate

The transition area between the hard and soft palate is a region where many ONF occur

because it is one of the areas of greatest tension during palatoplasty. The identification

of ONF in this region is complex due to morphological changes resulting from the fistula

healing process, resulting in retraction and anteriorization of the soft palate muscles,

giving the impression that the transition fistula extends to the hard palate or soft

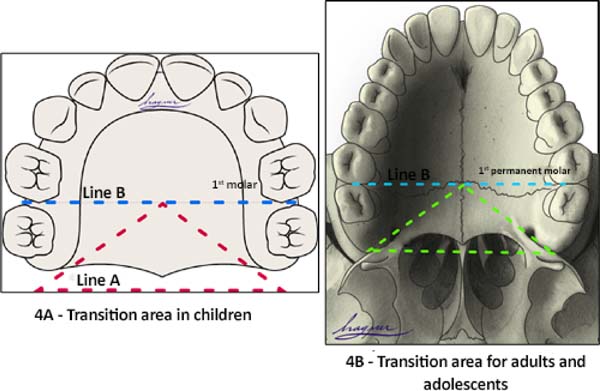

palate. To favor the process of identification of the transition area between the

hard palate and the soft, the Brosco-Dutka protocol establishes two imaginary lines

as illustrated in Figure 4:

Figure 4 - Illustration of lines A and B: A. In the child; B. In adulthood.

Figure 4 - Illustration of lines A and B: A. In the child; B. In adulthood.

• Line A: bordering the posterior alveolar edge (Tuber);

• Line B: tangential to the distal surface of the first molars in the deciduous and mixed

dentition in children (Figure 4A). In adults, line B touches the distal surface of the second molars (Figure 4B).

During the evaluation of the ONF, the transition area is that circumscribed to an

imaginary triangle whose base is formed by line A and the apex is at the central point

of line B. During the analysis of photographic images, if the photographic documentation

is inadequate, the definition of the transition area becomes complex or even impossible.

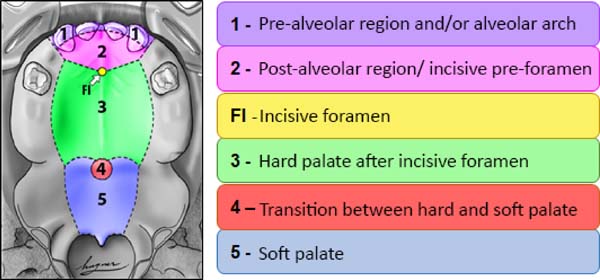

Embryological and morphological criteria

From the point of view of embryology, the fistula can be called fístula PREFI, POSFI

or PREPO (Figure 5). Regarding morphology, the fistula may occur in Regions 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 (Figure 6).

Figure 5 - After identifying the FI (yellow dot indicated by the white arrow on the images),

it is possible to establish whether the fistula occurs in the preforamen incisive

region (PREFI), in the post-foramen incisive region (POSFI), or FI it occurs in both

regions (PREPO).

Figure 5 - After identifying the FI (yellow dot indicated by the white arrow on the images),

it is possible to establish whether the fistula occurs in the preforamen incisive

region (PREFI), in the post-foramen incisive region (POSFI), or FI it occurs in both

regions (PREPO).

Figure 6 - Illustration of the 5 morphological regions of fistula and FI location.

Figure 6 - Illustration of the 5 morphological regions of fistula and FI location.

The embryological criterion analyzes the presence of the fistula in the primary and/or

secondary palate, according to its location in relation to the FI (Figure 5). The initial stage of application of the protocol, therefore, requires the identification

of the FI and the classification of the fistula in:

• PREFI: fistula located in a region before the FI (primary palate);

• POSFI: fistula located in the posterior region of the FI (secondary palate);

• PREPO: fistula that affects both the anterior and posterior fi region (primary and secondary

palate).

Then the morphological criterion is applied by verifying in which of the five regions

the ONF occurred, being possible the involvement of more than one morphological region

(Figure 6):

• Region 1: involves the pre-alveolar and/or alveolar arch;

• Region 2: involves the post-alveolar region (area of the hard palate anterior to FI)

• Region 3: involves the region of the hard palate after FI;

• Region 4: involves the transition region between the hard palate and the soft palate;

• Region 5: wraps the soft palate.

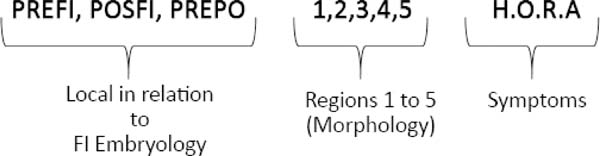

Symptomatology

The symptomatology can be observed by the professional during the clinical evaluation

in person, reported by the patient or his/her guardian or obtained from records in

the patient’s medical records. In the protocol, the word HORA was used to characterize the reported symptoms, as illustrated (Figure 7), where H refers to hypernasality and/or nasal air escape or other speech alteration; O refers to otitis and other otological symptoms; R refers to nasal reflux of food, and A refers to asymptomatic fistulas.

Figure 7 - Formula representing embryological, morphological and symptomatology findings.

Figure 7 - Formula representing embryological, morphological and symptomatology findings.

The coexistence of ONF and VFD makes the identification of speech-related symptoms

and swallowing more complex. Whenever possible, face-to-face evaluation of symptoms

should be performed under two conditions: with and without fistula filling. A fistula

may be temporarily combed with a dental material, host, or adhesive to retain dental

prosthesis. Even at the best of attempts, a fistula may not be fully sealed, which

always leaves doubts about VFD’s coexistence. The elimination of symptoms with fistula

sealing provides essential information for the definition of the conduct for fistula

correction. In cases of VFD, fistula-only repair does not correct symptoms arising

from velopharyngeal insufficiency. Instrumental evaluation of velopharyngeal functioning

for the speech employing nasopharyngoscopy and/or videofluoroscopy is necessary to

decide between operating only the fistula or associating this procedure with secondary

intravelar veloplasty for muscle repositioning of the soft palate.

At the end of the fistula evaluation on face-to-face examination or when performing

photographic image analysis in the Brosco-Dutka classification, the findings can be

represented by a formula combining the embryological, morphological and symptomatology

criteria (Figure 7).

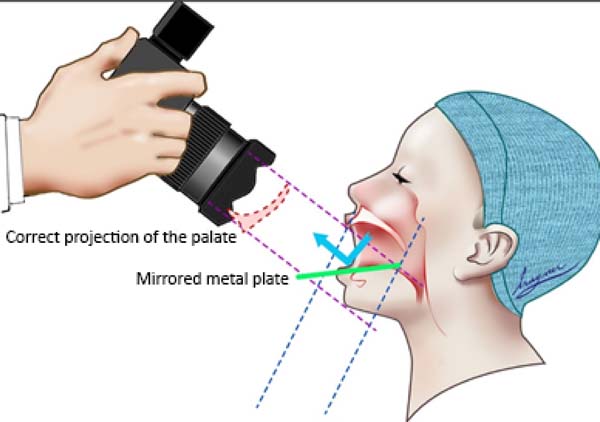

Photographic documentation

To obtain good photographic images for applying the Brosco-Dutka protocol, it is important

to use a mirror for the photograph of the intraoral region, positioned in adequate

angulation in relation to the occlusal plane (between 45º and 60º). The photographic

image should allow the visualization of the palatine face of the upper incisor teeth

instead of the vision of the anterolabial face of the same. The image in Figure 8 illustrates the proper positioning of the mirror and camera during the photoshoot.

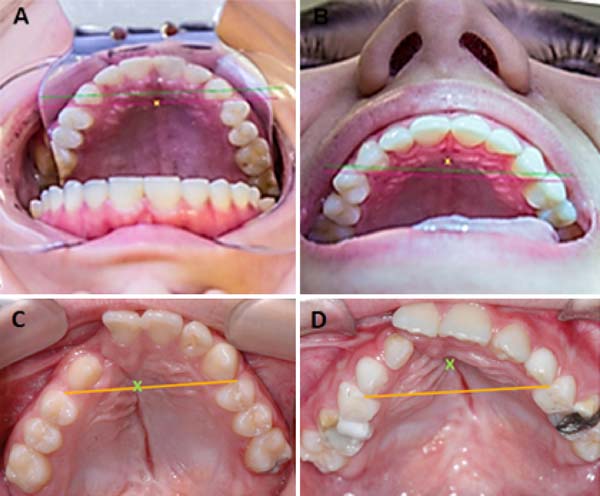

The images of Figures 9A and 9B illustrate the appropriate photographic image (Figure 9A) and inadequate photographic taking (Figure 9B) in an individual without FLP. Figures 9C and 9D illustrate the appropriate (Figure 9C) and inadequate (Figure 9D) photo in an individual with FLP. For the complete photographic visualization of

the palate, two photographic shots are required: using the mirror for the anterior

region and direct take of the soft palate with or without the use of the mirror for

the posterior region. With a single photograph, proper photographic viewing of the

entire palate (hard and soft) is limited due to the configuration of the palate.

Figure 8 - Adequate position for photographing using the dental mirror.

Figure 8 - Adequate position for photographing using the dental mirror.

Figure 9 - Positioning for photographic image and fistula documentation. A and C. They show the

palatine face of the incisor teeth in an individual without and with FLP. The tracing

of the incisive line allows the correct identification of the FI, B, and D. They illustrate

the inadequate positioning of the photographic image showing the labial face of the

incisor teeth in an individual without and with FLP. In this case, the incisive line

tracing does not allow the proper location of the FI.

Figure 9 - Positioning for photographic image and fistula documentation. A and C. They show the

palatine face of the incisor teeth in an individual without and with FLP. The tracing

of the incisive line allows the correct identification of the FI, B, and D. They illustrate

the inadequate positioning of the photographic image showing the labial face of the

incisor teeth in an individual without and with FLP. In this case, the incisive line

tracing does not allow the proper location of the FI.

RESULTS

The Brosco-Dutka palate fistula classification protocol is presented in Annex 1.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of ONF is considered one of the indicators of failure of primary surgical

treatment of FLP6-8. Although the literature presents publications on the individual and institutional

results of complications after palatoplasty, it is also observed the absence of a

standardized and universally accepted definition of the concept of fistula13,14,19. Several definitions of fistulas have been used in the literature, including failure

in healing or rupture of surgical repair of the palate18,27 or permeability between the oral and nasal cavity13,23,28,29. The absence of the standardized definition of fistula results in great variability

of the occurrence rates of ONF 14, introducing biases and compromising the establishment of this index8.

The description of inclusion and exclusion criteria of ONF in publications is also

limited, with great heterogeneity among researchers. Some exclude fistulas before

FI and intentionally unrepaired, considering only fistulas on the secondary palate2,13,18-23. Documenting only fistulas on the secondary palate modifies the occurrence rate of

ONF, and FI is the criterion applied; it should be clearly indicated in the publication.

A fistula classification system that can be applied with good reliability among team

members is considered essential for adequate control of the variation of the ONF indices

8,13,18. The classification systems of Cohen18 and Pittsburgh13 were based on anatomical criteria and did not mention the symptoms. Sitzman et al.

(2016) 8 evaluated the reliability of the Pittsburgh fistula classification system, involving

eight surgeons as evaluators. The results indicated that the Pittsburgh classification

showed good intra-rater reliability, but the inter-rater agreement rates were not

as good as expected. Inadequate photographic documentation was one of the limiting

factors cited by the authors.

The Richardson and Agni classification system (2014)25 proposes an algorithm for fistula management based on parameters that involve:

1)the size of the fistula (longitudinal or transverse); 2) the affected site (soft

palate and uvula, posterior and middle hard palate, hard anterior palate); 3) classification

of the cleft (unilateral, bilateral); and 4) number of previous surgical procedures

on the palate. According to the authors, the proposed classification allows the surgeon

to assess the degree of difficulty in correcting the fistula and predicting the prognosis

of the procedure. More recently, a classification system for palate fistula was proposed

by Fayyaz (2019)24. The authors published a very expressive series of 2,537 fistulas that were analyzed.

The classification is based on four characteristics: 1) location of the fistula, 2)

fistula size, 3) velopharyngeal competence, and 4) presence of dehiscence. When present,

multiple fistulas were reported. The algorithm proposed by the authors makes it possible

to establish guidelines for surgical management. Fayyaz (2019)24 mentions that the correction of velopharyngeal insufficiency is performed together

with the correction of the fistula. Still, he does not report the use of nasoendoscopy

and videofluoroscopy of velopharyngeal functioning during the process of defining

the conduct for managing VFD.

The classification proposed in the present study, although similar to those proposed

by Cohen et al. (1991) 18 and Smith et al. (2007) 13, includes five possible regions

of occurrence instead of 7 and proposes criteria that favor the identification of

anatomical references essential for the application of the new protocol. The introduction

of the incisor line (to assist in locating the FI) and lines A and B (to assist in

locating the transition area between hard and soft palate) aim to favor greater reliability

among the evaluators during the application of the classification system. In cases

with severe surgical sequelae involving bone deformities and significant loss of dental

elements, this classification may not be completely applicable due to the absence

of reference elements.

It is also proposed that this protocol be used to document fistulas intentionally

left by the surgeon at the time of primary palatoplasty. In addition, asymptomatic

fistulas and punctate fistulas (micro-fistulas) should be documented with a clear

indication of their clinical condition of no relevance for speech. , food and hearing.

Only with this care of registering all possible occurrences of fistula will future

comparative studies be able to generate adequate scientific evidence of the actual

occurrence of ONF, thus contributing to the prevention and treatment of these complications7.

The complete record of data on post-surgical complications should be inserted in the

patient’s medical records in a protocol for evaluating these occurrences, being fundamental

for adequate documentation of the institutional results of the management of the FLP.

Obtaining quality photographic images that allow visualization of the complete palate

is essential to verify reliability during protocol application. Different services

may establish different strategies for intraoral photography, and it is possible to

use the dental chair with a mirror or the surgical table with the patient anesthetized

for the correction of the fistula. Image quality should be audited periodically, ensuring

appropriate, photographic collections for future national and international intercenter

studies. The team’s training (surgeon, dentist and speech therapist) for the protocol

application is essential in the routine of specialized services, being recommended

a periodic calibration and establishing strategies to improve or maintain intra and

inter-rater reliability.

CONCLUSION

The Brosco-Dutka protocol of classification of the palate fistula has as its main

purpose its use by a multidisciplinary team, aiming to enable both intra and craniofacial

intercenters. Although it is possible to apply it in live outpatient consultations,

it is recommended to obtain good photographic images of the palate so that the classification

of post-surgical complications can be made by multiple evaluators internal and external

to the craniofacial center evaluated. The classification of fistula by multiple evaluators,

in turn, requires adequate photographic documentation, including documentation of

fistula-related symptomatology.

The protocol defines what fistula is and standardizes the terminology to be used by

the multidisciplinary team. The proposed classification is based on embryological

and morphological criteria, including strategies for identifying anatomical references

of complex visualization. Based on the care highlighted by the authors, the application

of the protocol allows systematic and standardized monitoring of the occurrence of

ONF, favoring the identification of the relevance of these complications for speech,

hearing and feeding. The clinical validation of this protocol is necessary, and future

studies involving its application should clarify the inclusion and exclusion criteria

of ONF. It is essential to state in the methodology whether fistulas intentionally

left by the surgeon (which are not considered surgical complications) and asymptomatic

fistulas (which do not require surgical or prosthetic management), for example, will

be computed in the general percentage of the occurrence.

REFERENCES

1. Silva Filho OG, Freitas JAS. Caracterização morfológica e origem embriológica. In:

Trindade IEK, Silva Filho OG, coordenadores. Fissuras labiopalatinas: uma abordagem

interdisciplinar. São Paulo: Santos; 2007. p. 17-49.

2. Williams WN, Seagle MB, Pegoraro-Krook MI, Souza TV, Garla L, Silva ML, et al. Prospective

clinical trial comparing outcome measures between Furlow and von Langenbeck palatoplasties

for UCLP. Ann Plast Surg. 2011 Fev;66(2):154-63.

3. Deshpande GS, Campbell A, Jagtap R, Restrepo C, Dobie H, Keen HT, et al. Early complications

after cleft palate repair: a multivariate statistical analysis 709 of patients. J

Craniofac Surg. 2014;25(5):1614-8.

4. Passos VAB, Carrara CFC, Dalben GS, Costa B, Gomide MR. Prevalence, cause and location

of palatal fistula in operated complete unilateral cleft lip and palate: retrospective

study. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2014 Mar;51(2):158-64.

5. Aslam M, Ishaq I, Malik S, Fayyaz GQ. Frequency of oronasal fistulae in complete cleft

palate repair. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2015 Jan;25(1):46-9.

6. Eberlinc A, Koželj V. Incidence of residual oronasal fistulas: a 20-year experience.

Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2012 Nov;49(6):643-8.

7. Hardwicke JT, Landini G, Richard BM. Fistula incidence after primary cleft palate

repair: a systematic review of the literature. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014 Out;134(4):618e-27e.

8. Sitzman TJ, Allori AC, Matic DB, Beals SP, Fisher DM, Samson TD, et al. Reliability

of oronasal fistula classification. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2018 Jul;55(6):871-5.

9. Xu JH, Chen H, Tan WQ, Lin J, Wu WH. The square flap method for cleft palate repair.

Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2007 Nov;44(6):579-84.

10. Stewart TL, Fisher DM, Olson JL. Modified Von Langenbeck cleft palate repair using

an anterior triangular flap: decreased incidence of anterior oronasal fistulas. Cleft

Palate Craniofac J. 2009 Mai;46(3):299-304.

11. Dong Y, Dong F, Zhang X, Hao F, Shi P, Ren G, et al. An effect comparison between

Furlow double opposing Z-plasty and two-flap palatoplasty on velopharyngeal closure.

Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012 Mai;41(5):604-11.

12. Mak SY, Wong WH, Or CK, Poon AMS. Incidence and cluster occurrence of palatal fistula

after furlow palatoplasty by a single surgeon. Ann Plast Surg. 2006 Jul;57(1):55-9.

13. Smith DM, Vecchione L, Jiang S, Ford M, Deleyiannis FWB, Haralam MA, et al. The Pittsburgh

fistula classification system: a standardized scheme for the description of palatal

fistulas. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2007 Nov;44(6):590-4.

14. Bykowski MR, Naran S, Winger DG, Losee JE. The rate of oronasal fistula following

primary cleft palate surgery: a meta-analysis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2015 Jul;52(4):e81-7.

15. Timbang MR, Gharb BB, Rampazzo A, Papay F, Zins J, Doumit G. A systematic review comparing

Furlow opposing Z-plasty and straight-line intravelar veloplasty methods of cleft

palate repair. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014 Nov;134(5):1014-22.

16. Salimi N, Aleksejuniene J, Yen EHK, Loo AY. Fistula in cleft lip and palate-a systematic

scoping review. Ann Plast Surg. 2017 Jan;78(1):92-102.

17. Hardwicke J, Nassimizadeh M, Richard B. Reporting of randomized controlled trials

in cleft lip and palate: a 10-year review. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2017 Mar;54(2):142-52.

18. Cohen SR, Kalinowski J, LaRossa D, Randall P. Cleft palate fistulas: a multivariate

statistical analysis of prevalence, a etiology and surgical management. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 1991 Jun;87(6):1041-7.

19. Emory RE, Clay RP, Bite U, Jackson IT. Fistula formation after palatal closure: an

institutional perspective. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997 Mai;99(6):1535-8.

20. Diah E, Lo LJ, Yun C, Wang R, Wahyuni LK, Chen YR. Cleft oronasal fistula: a review

of treatment results and a surgical management algorithm proposal. Chang Gung Med

J. 2007 Nov/Dez;30(6):529-37.

21. Phua YS, Chalain T. Incidence of oronasal fistulae and velopharyngeal insufficiency

after cleft palate repair: an audit of 211 children born between 1990 and 2004. Cleft

Palate Craniofac J. 2008 Mar;45(2):172-8.

22. Losken HW, Van Aalst JA, Teotia SS, Dean SB, Hultman S, Uhrich KS. Achieving low cleft

palate fistula rates: surgical results and techniques. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2011;48(3):312-20.

23. Rossell-Perry P, Segura E, Salas-Bustinza L, Cotrina-Rabanal O. Comparison of two

models of surgical care for patients with cleft lip and palate in resource-challenged

settings. World J Surg. 2015 Jan;39(1):47-53.

24. Fayyaz GQ, Gill NA, Ishaq I, Aslam M, Chaudry A, Ganatra MA, et al. Pakistan comprehensive

fistula classification: a novel scheme and algorithm for management of palatal fistula/dehiscence.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019 Jan;143(1):140e-51e.

25. Richardson S, Agni NA. Palatal fistulae: a comprehensive classification and difficulty

index. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014 Set;13(3):305-9.

26. Jacob MF, Prearo GA, Brosco, TVS, Silva, HLA, Dutka, JCR. Fístula após palatoplastia

primária: Consenso entre profissionais da cirurgia plástica e da fonoaudiologia. Rev

Bras Cir Plást. 2020;35(2):142-8.

27. Muzaffar AR, Byrd HS, Rohrich RJ, Johns DF, LeBlanc D, Beran SJ, et al. Incidence

of cleft palate fistula: an institutional experience with two-stage palatal repair.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001 Nov;108(6):1515-8.

28. Rennie A, Treharne LJ, Richard B. Throat swabs taken on the operating table prior

to cleft palate repair and their relevance to outcome: a prospective study. Cleft

Palate Craniofac J. 2009 May;46(3):275-9.

29. Lu Y, Shi B, Zheng Q, Hu Q, Wang Z. Incidence of palatal fistula after palatoplasty

with levator veli palatini retropositioning according to Sommerlad. Br J Oral Maxillofac

Surg. 2010 Dez;48(8):637-40.

30. Brosco TVS. Fístula de palato após reparo da fissura labiopalatina em um estudo clínico

randomizado [tese]. Bauru (SP): Universidade de São Paulo - Hospital de Reabilitação

de Anomalias Craniofaciais; 2017.

31. Silva HLA. Atlas de cirurgia plástica na fenda labiopalatal [dissertação]. São Paulo

(SP): Universidade de São Paulo - Hospital de Reabilitação de Anomalias Craniofaciais;

2019.

1. Craniofacial Anomalies Rehabilitation Hospital of the University of São Paulo -

HRAC-USP, Bauru, SP, Brazil.

2. University of São Paulo, Bauru Dental School, Bauru, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Telma Vidotto de Sousa Brosco, Rua Sílvio Marchione, 3-20, Vila Nova Cidade Universitária, Bauru, SP, Brazil. Zip

Code: 17012-900 E-mail: telmabrosco@gmail.com

Article received: July 21, 2020.

Article accepted: April 23, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none

COLLABORATIONS

TVSB Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation,

Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project Administration, Writing

- Original Draft Preparation

GAP Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology,

Writing - Original Draft Preparation

HLAS Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing

JCRD Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation,

Final manuscript approval, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project Administration, Supervision,

Writing - Original Draft Preparation