Original Article - Year 2021 - Volume 36 -

Systematization of reconstruction of the abdominal wall after reconstruction with TRAM

Sistematização de reconstrução da parede abdominal pós-reconstrução com TRAM

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Tram (transverse abdominal rectum flap) has remained the most used autologous breast reconstruction method over the last 30 years. First described by Holmström, the flap allows breast reconstruction with analogous tissue, providing natural appearance and consistency and lasting results. Reconstruction of the abdominal wall of the defect installed after flap transposition is a major challenge, and there is no consensus on the form for elevation or closure of the abdominal wall flap. The article aims to present a practical method for abdominal wall reconstructions to reduce morbidity in patients undergoing breast reconstruction with TRAM.

Methods: This is a descriptive work of a systematic abdominal wall reconstruction technique using propylene mesh.

Result: Once the technique is applied, we have an abdominal wall covered with polypropylene fabric, fully fixed and well adapted. The systematization of abdominal wall reconstruction after reconstruction with TRAM was performed, which is characterized by being easy to reproduce and applicable.

Conclusion: The technique is a good alternative in abdominal wall reconstructions for the surgeon, systematizing polypropylene mesh adaptation.

Keywords: Abdomen; Abdominal wall; Reinforcement of structures; Hernia; Mama.

RESUMO

Introdução: O TRAM (retalho do músculo reto abdominal transverso) manteve-se o método mais utilizado de reconstrução autóloga de mama ao longo dos últimos 30 anos. Descrito pela primeira vez por Holmström, o retalho permite a reconstrução mamária com tecido análogo, proporcionando aparência e consistência natural e resultados duradouros. A reconstrução da parede abdominal do defeito instalado após a transposição do retalho é um grande desafio e não há consenso sobre qual é a forma para elevação ou fechamento do retalho da parede abdominal. O artigo tem como objetivo apresentar um método prático para reconstruções de parede abdominal, visando diminuir a morbidade em pacientes submetidos à reconstrução de mama com TRAM.

Métodos: Esse é um trabalho descritivo de uma técnica sistemática de reconstrução de parede abdominal com utilização de tela de propileno.

Resultado: Aplicada a técnica teremos uma parede abdominal coberta com uma tela de polipropileno, totalmente fixa e bem adaptada, foi realizada a sistematização na reconstrução de parede abdominal após reconstrução com TRAM que se caracteriza por ser de fácil reprodução e aplicabilidade.

Conclusão: A técnica se mostra uma boa alternativa em reconstruções de parede abdominal para o cirurgião, sistematizando a adaptação da tela de polipropileno.

Palavras-chave: Abdome; Parede abdominal; Reforço de estruturas; Hérnia; Mama

INTRODUCTION

Despite the increasing number of surgical options for breast reconstruction, the TRAM (Transverse rectus abdominis muscle flap) flap has remained the most used autologous breast reconstruction method over the last 30 years. The use of autologous abdominal tissue allows a natural appearance of breast reconstruction, providing the sensation of normal breast tissue, in addition to improving body contouring1,2.

The TRAM was first described by Holmström in 20063 and popularized by Hartrampf et al. in 19874 and Gandolfo in 19965. The TRAM flap allows breast reconstruction with analogous tissue, providing natural appearance and consistency, and lasting results3.

There are many different techniques for creating flaps, such as unipediculated, bipediculated, and microsurgical TRAM flaps. However, these techniques create defects of various severity levels in the abdominal wall, with the hernia and abdominal bulging being the most common late complications5.

Reconstruction of the abdominal wall can be performed at several levels of complexity, correcting mild tissue substance losses until critical defects of the total thickness, with visceral involvement1. Among the various causes of an abdominal injury, incisional hernia, neoplasia, infection, irradiation, and trauma stand out6.

Reconstruction of the abdominal wall at the flap’s donor site is a great challenge, and there is no consensus on which is the best technique for lifting or closing the flap of the abdominal wall7,8.

There are many relevant techniques for closing the anterior abdominal wall, such as preserving the rectus abdominis muscle and the anterior rectus sheath and replacing structures removed by synthetic meshes or autologous grafts and flaps, trying to reduce morbidity at the donor site3,5.

OBJECTIVES

Present a practical method of systematization of abdominal wall reconstruction, aiming to reduce morbidity in patients undergoing breast reconstruction with TRAM.

METHODS

This is a descriptive study on the surgical technique of abdominal wall reconstruction after mammary reconstruction with TRAM using polypropylene mesh. This systematization is performed in abdominal wall reconstructions in plastic surgery patients at the Regional Hospital of Sobradinho, Federal District. The study does not expose patient data, only illustrative images for technique description, following Helsinki criteria.Technique

RESULTS

Technique

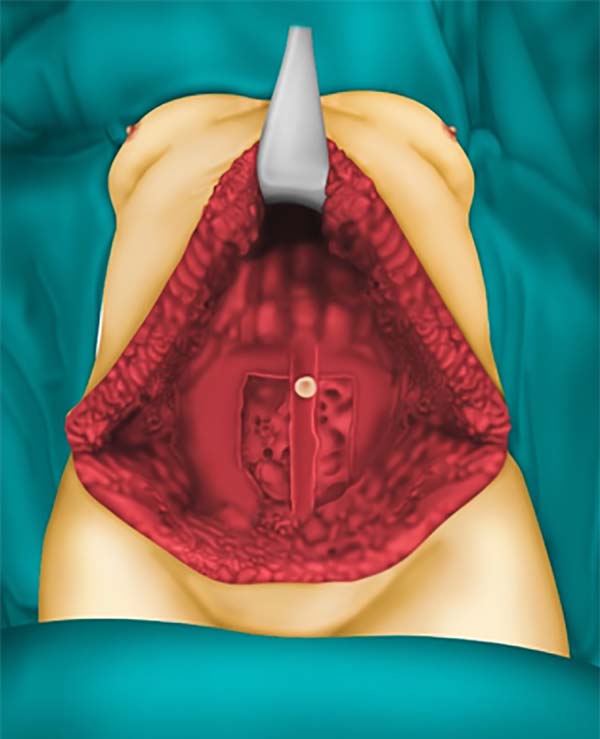

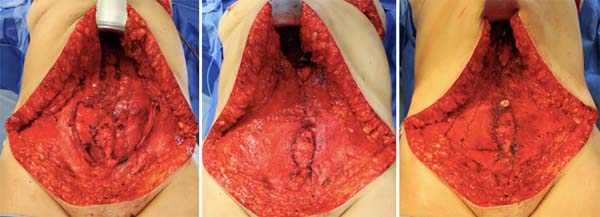

After performing the transverse rectus abdominis muscle flap and its transposition for mammary reconstruction, a vital defect arises concerning the abdominal wall. When lifting the flap, a thin wall is left in place with fragility and great potential to evolve with bulging or even abdominal hernias (Figure 1).

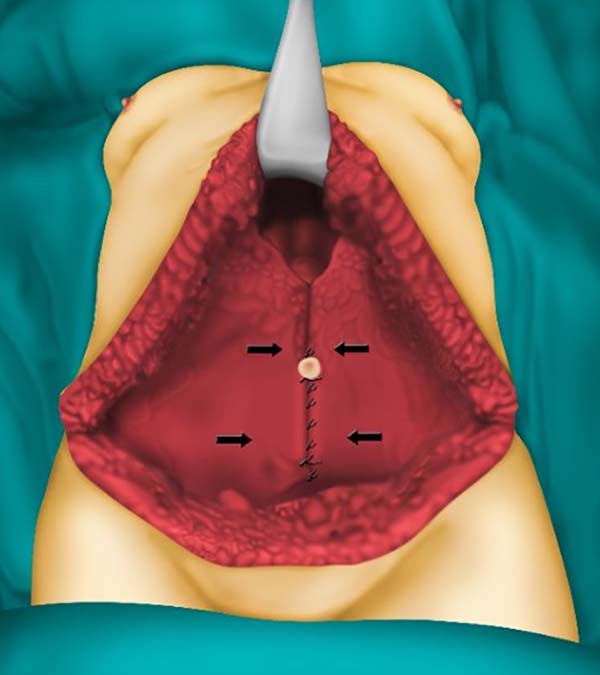

To prevent complications, such as bulging and hernias, we performed reconstruction of the abdominal wall using polypropylene mesh. The approximation of rectus aponeurosis with nylon 2.0 points in X is performed in those patients in which there is a possibility, further increasing the reinforcement of the abdomen (Figure 2).

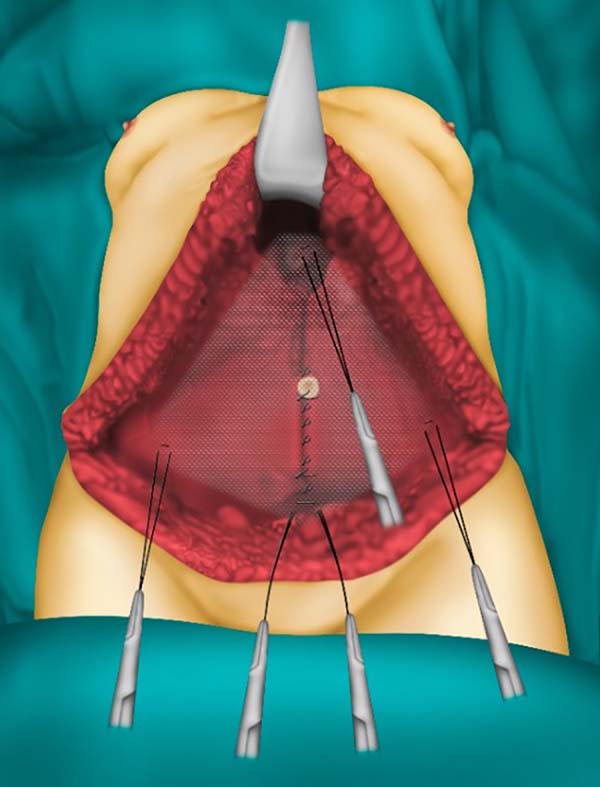

To facilitate schematization, we use the following symbologies:

Initially, we positioned the intact mesh on the abdominal defect and fixed the a-spot with two parallel points with nylon 2.0, leaving the wires uncut. Then, the screen is fixed at point C with two parallel points with nylon 2.0, leaving the wires uncut. It is then performed the fixation with nylon 2.0 at points B1 and B2, with the detail in passing the needle on the screen 2cm medial to points B1 and B2, where they will be fixed, to cause traction on the screen, leaving it tense and fully stretched. Then, the screen’s excess is cut, leaving only the part within the fixed areas, forming a rummage image (Figure 3).

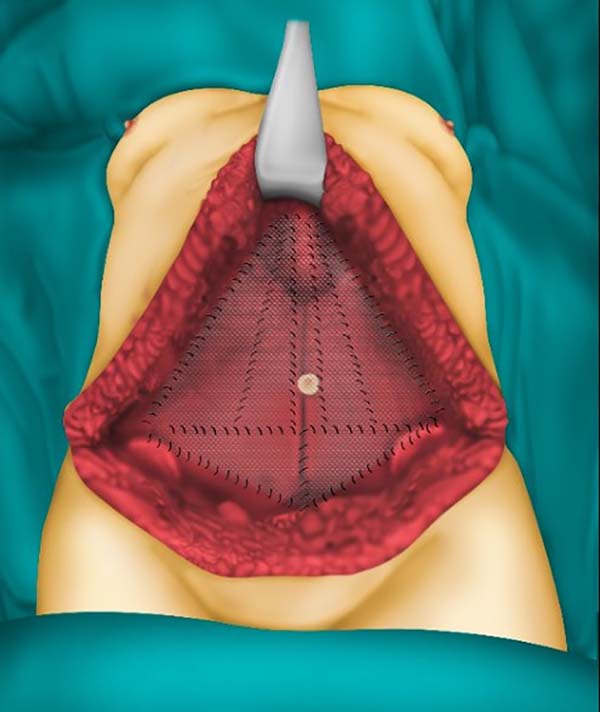

After performing the screen’s cardinal points, we then used the same wires, already tied, to perform the fixation of the edges and middle of the screen. Using the fixation wire of point A, continuous points are made at the lower margin of the screen, at the height of 2cm above the inguinal ligaments, up to points B1 and B2, and continues to point D, where they will then be tied. The threads of points B1 and B2 are used to perform the continuous sutures on the upper edges of the canvas to point C, and then the continuous sutures are performed in the bisectors of the triangles formed by points B1, B2 and C, and then tied. With the threads of point C, sutures are made to point D in parallel and then tied (Figure 4).

In cases that the rectus abdominis muscle fascia cannot be sutured or in which the abdominal defect is a large area, either due to lack of fascia during the lifting of the muscle flap or by voluminous ventral hernias, another layer of fabric should be placed in order to ensure the closure of the abdominal performance. In these cases, double-plane screen placement is recommended to prevent recurrences of hernias or their appearance.

After fixing the screen with the technique described above, we will have an abdominal wall covered with polypropylene fabric, entirely fixed and well adapted (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

The rectus abdominis originates anteriorly from the previous faces of the fifth to the seventh costal cartilages and xiphoid process, inserting on the pubis. It is characterized by being a long and segmented muscle. Its irrigation is classified as type III of Mathes and Nahai (upper and lower epigastric artery), having between six and ten skin perforators; being widely used in breast reconstructions, such as the transverse myocutaneous flap (TRAM)7-9.

Hernias, the main etiology of abdominal wall defects in the world literature, have a wide variety of treatments available. The main modality for minor hernial defects would be primary synthesis; in moderate to large defects, alloplastic screen placement can be associated10. According to the literature, the incidence of hernias and bulging after mammary reconstruction with TRAM reaches about 10% using nonabsorbable fabric11.

An essential concern among plastic surgeons who use TRAM in routine mammary reconstructions is the abdominal wall’s competence in the postoperative period. Low rates of hernias or bulging, abdominal stability, and slight sagging are the most critical current expectations for successful abdominal closure9. During reconstruction with TRAM, a segmental defect in the rectus abdominis muscle is left and exposes the region located below the arched line of Douglas, characterized by being fragile because it does not have an aponeurotic coating. Non-closure or incorrect reconstruction can lead to a high risk of abdominal hernia or bulging at the site of the defect.

Hartrampf et al., in 19874, reported in a review of cases complications related to abdominal wall closure without the use of screens in surgeries with TRAM and noted that this number was associated with the progressive improvement of the surgical technique8. Other authors such as Suominen, in 199612 and Lallement, in 199413, showed in his studies that the percentage of hernias and bulging of the abdominal region after the TRAM, with primary closure of the donor site, was 12.5 to 20% and 20 to 44%10,12 respectively, not being able to reproduce the same results published by Hartpf in 19874.

Kroll and Marchi, in 199214, demonstrated a decrease of 35% to 6% in complications related to hernias and bulging with primary closure of the abdominal site, after the introduction of the routine use of Marlex mesh with two suture plans10,4,14. This was reaffirmed shortly afterward by Watterson in 19957, showing a decrease from 16% to 4% of complications after using polypropylene mesh10,12. Some authors have published studies revealing a rate of 1.5% of such complications with polypropylene mesh and 0% using Gore-Tex mesh5,8,10. These results are also barely reproducible, according to the world literature.

The main surgical goals should include the restoration of the musculofascial wall’s function and integrity, obtaining stable skin coverage of soft tissues, and aesthetic optimization15.

In this work technique, we performed a systematization in abdominal wall reconstruction after reconstruction with TRAM, which is characterized by being easy to reproduce and applicability.

CONCLUSION

The proposed technique presents a great possibility of reproduction, making it easy to perform a systematization. It has advantages over the techniques discussed, becoming an essential alternative to plastic surgeons who perform breast reconstruction with TRAM and sizeable abdominal wall defects. The systematization ensures good fixation of the screen and decreases surgical time, promoting less exposure and handling the screen to the external environment.

REFERENCES

1. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Coordenação de Prevenção e Vigilância. Estimativa 2018: incidência de câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: Ministério da Saúde/INCA; 2017.

2. Machado WA, Pessoa SGP, Muniz VV. Complicações em reconstrução mamária com retalho transverso de músculo reto abdominal (TRAM) em hospital público de Fortaleza, nos últimos 5 anos. Rev AMRIGS. 2016 Dez;60(4):333-6.

3. Glasberg SB, D'Amico RA. Use of regenerative human acellular tissue (AlloDerm) to reconstruct the abdominal wall following pedicle TRAM flap breast reconstruction surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Jul;118(1):8-15.

4. Hartrampf CR. Breast reconstruction with a transverse abdominal island flap: a retrospective evaluation of 355 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987 Fev;(1):123-7.

5. Pennington DG, Lam T. Gore-Tex patch repair of the anterior rectus sheath in free rectus abdominis muscle and myocutaneous flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996 Jun;97(7):1436-42.

6. Roxo CP, Carvalho TM, Borba MA, Silva LRB, Roxo ACW. Reconstrução de parede abdominal com tela aloplástica após infecção por micobactéria. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012 Jun;27(2):340-3.

7. Watterson PA, Bostwick J, Hester Junior TR, Bried JT, Tayolor GI. TRAM flap anatomy: correlated with a 10-year clinical experience with 556 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995 Jun;95(7):1185-94.

8. Keppke EM. TRAM bipediculado com preservação dos músculos retos do abdomen abaixo da linha arqueada de Douglas sem o uso de tela de reforço. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012;27(1):49-57.

9. Cammarota MC, Almeida CM, Faria CADC, Daher JC, Camara Filho JPP, Esteves BP, et al. Breast reconstruction with the transverse rectus abdominis flap: an alternative technique for the closure of abdominal defects. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;29(4):531-7.

10. Neligan PC. Cirurgia plástica: mama. 3ª ed. Rio de Janeiro: Elsevier; 2015. v. 5.

11. Schmaltz EGSC, Jorge JLG, Andrade CZN, Silva MF, Farina Junior JA. Abdominal wall repair with double-mesh polypropylene/ polyglecaprone after TRAM flap surgery for breast reconstruction. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2014;29(4):544-9.

12. Suominen S, Asko-Seljavaara S, Von Smitten K, Ahovuo J, Sainio P, Alaranta H. Sequela in the abdominal wall after pedicle or free TRAM flap surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 1996 Jun;36(6):629-36.

13. Lallement, S., et al. Closure of the abdominal wall after removal of a myocutaneous flap from the transverse rectus abdominis for breast reconstruction. Apropos of 48 Cases. Review of the literature. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 39:733, 1994.

14. Kroll SS, Marchi M. Comparison of strategies for preventing abdominal wall weakness after TRAM flap breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992 Jun;89(6):1045-51;discussion:1052-3.

15. Kawamura K, Luna ICG, Anlicoara R, Lopes PS, Lima MFMB. Reconstruction of the abdominal wall: a case series. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2018;33(1):56-63.

1. Hospital Daher Lago Sul, Plastic Surgery,

Brasilia, DF, Brazil.

2. AC Clinica, Plastic Surgery Clinic, Brasilia,

DF, Brazil.

ASC Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Project Administration, Realization of operations and/or trials, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization

RSCC Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript approval, Methodology, Realization of operations and/or trials, Visualization, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

JCD Conceptualization, Validation, Visualization

SVS Analysis and/or data interpretation, Data Curation, Visualization

COPC Analysis and/or data interpretation, Writing - Original Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing, Data Curation

AAD Analysis and/or data interpretation, Realization of operations and/or trials, Visualization

Corresponding author: Rafael Sabino Caetano Costa, Quadra SHIS QI 7, Conjunto F, Área Especial F, Setor de Habitações Individuais Sul, Brasília, DF, Brazil. Zip Code: 71615-660. E-mail: rafaelsabinomed@gmail.com

Article received: November 24, 2019.

Article accepted: January 10, 2021.

Conflicts of interest: none

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter