INTRODUCTION

The use of autologous fat grafting to correct defects was first described over 100

years ago when it was used to correct facial defects. Concurrently a back lipoma was

also used to recreate a patient’s breast after mastectomy1.

The contemporary evolution of autologous fat grafting was popularized by Coleman et

al., in 20102, who described the use of liposuction and adipocyte purification for injecting into

the face as a soft tissue filling. Then, Bircoll and Novack (1987 apud Costantini

et al.), extended this use to breasts3,4.

The interest in fat injection was revived in the early 1990s by Coleman, who confirmed

that adipose tissue could be satisfactorily transferred by stipulating that a strict

protocol for fat preparation and injection should be respected2,5.

Coleman’s fat grafting technique is by far the most commonly used. The adipose tissue

is infiltrated with a tumescent solution (for example, Klein’s solution) and then

manually harvested through skin incisions using a 3 mm cannula with two holes and

blunt tip connected to a 10 mL syringe. The liposuction material is subsequently centrifuged

for three min at 3,000 rpm to isolate the adipose tissue from the oily and aqueous

fraction and then injected. The entire procedure can be performed under local anesthesia2,6.

The analysis of different anesthetic drugs showed greater viability of adipose stem

cells in adipose tissue treated with bupivacaine, mepivacaine, ropivacaine, and lidocaine

compared to the combined treatment with articaine and epinephrine. Although no variability

between amides is expected, epinephrine can affect α1 receptors in adjacent tissues

that support the implanted cells. In general, the tumescent solution improved cell

viability compared to the dry technique. No significant differences were observed

between the commonly used anesthetics, except for articaine and epinephrine7.

Transferring fat from an excess area such as the abdomen or thighs to improve the

shape and volume of the breast is not a new idea. A study by Illouz, in 19838, promoted the widespread use of liposuction worldwide, making the use of fat from

adipose deposits to increase breast volume.

The injected amounts varied from 100 to 250 mL in each breast6. In 20009, Fournier carefully affirmed that the fat was only injected in the retro glandular

space and not in the mammary parenchyma.

Fat grafting has also been used to treat burn scars. The evolution of the scarring

one year after treatment was evaluated using a questionnaire as well as physical and

histopathological exams. In the first year of follow-up, all patients reported improved

clinical condition. Histological findings showed new collagen deposition, neoangiogenesis,

and dermal hyperplasia in the context of new tissue, demonstrating tissue regeneration10.

Postoperative mammographic images to control fat necrosis vary. These can present

as lipid cysts, suspected malignant findings such as grouped microcalcifications,

spiculated areas of increased opacity, and focal masses10.

Fat necrosis is a nonspecific histological finding that involves several processes

in its etiopathogenesis. In addition to surgery, the most common causes of fat necrosis

are ischemia, radiation therapy, and trauma. There are reports of some other rare

occurrences of breast fat necrosis caused by anticoagulant therapy with sodium warfarin

(Coumadin) and sodium enoxaparin. Calciphylaxis, which is hypersensitivity to local

calcinosis associated with secondary hyperparathyroidism in renal failure, has also

been reported10.

An increased incidence of cancer after fat grafting was reported in reviews of studies

with animals, proving this hypothesis, but there was no evidence of this in in vitro studies11.

OBJECTIVE

To conduct a literature review on the use of fat grafting in breast reconstructions

with expanders and implants, and report three cases of patients undergoing the procedure

in a private clinic in Fortaleza.

METHODS

A bibliographic review was conducted using the scientific research databases, BIREME,

NCBI, PubMed, and SciELO, as well as on studies published in the journals of the Brazilian

and American Society of Plastic Surgery.

Three cases of patients who underwent breast reconstruction using prostheses and expanders

associated with fat grafting will be described. The incisions were made in the fat

donor areas using a No. 15 scalpel blade. Abdominal fat was aspirated through two

lateral incisions in the flanks using a 3 mm cannula with three holes connected to

a 60 mL syringe.

The fat was injected in small amounts in the shape of thin cylinders by retro-infusion.

It was necessary to create micro-channels in many directions. The transfer was made

from a deep to a superficial plane. Good spatial visualization was necessary to form

a kind of three-dimensional honeycomb to avoid fat pockets forming that would lead

to fat necrosis.

The fat graft was prepared using the sedimentation method. Fat processing is necessary

because the liposuction material contains not only adipocytes but also collagen fibers,

blood, and debris.

The preoperative evaluation was based on anthropometric methods, and the patients

were followed up monthly with a breast ultrasound to control fat grafting and mammography

according to age.

Case 1: Female, 65 years old, married, underwent a total right mastectomy in 2002 and total

left mastectomy in 2008, with immediate reconstruction with 200 mL and 250 mL prostheses,

respectively. The patient returned in 2016 to correct breast asymmetry. Personal morbid

history: nipple-areola complex radiotherapy and hormone therapy for five years. On

examination: asymmetric breasts with grade one ptosis with a bilateral contracture

(Baker 3), which was more intense on the right side and absence of fat tissue bilaterally.

The prostheses were removed and new ones with 332 mL and 350 mL were placed on the

right and left breasts, respectively, in addition to fat grafting of 80 mL on the

right and 60 mL on the left. Second fat grafting was completed two months later using

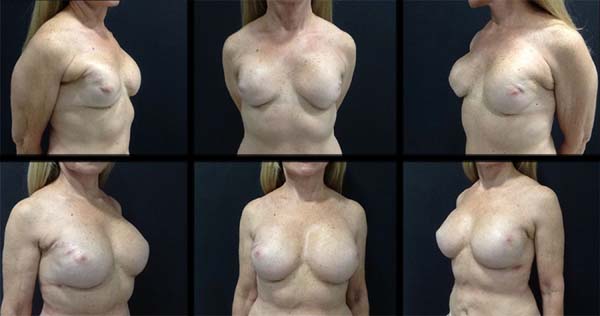

70 mL on the right and 80 mL on the left (Figure 1).

Figure 1 - Clinical case no. 1.

Figure 1 - Clinical case no. 1.

Case 2: Female, 75 years old, married, underwent total right mastectomy due to in situ ductal carcinoma, with a late reconstruction with transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous

(TRAM) flap in 2007. The patient sought the service due to dissatisfaction with the

obtained result. Personal morbid history: mother with lung and breast melanoma. A

350 mL expander prosthesis was placed on the right breast in December 2015. In June

2016, the right expander was replaced by a 350 mL silicone prosthesis and the left

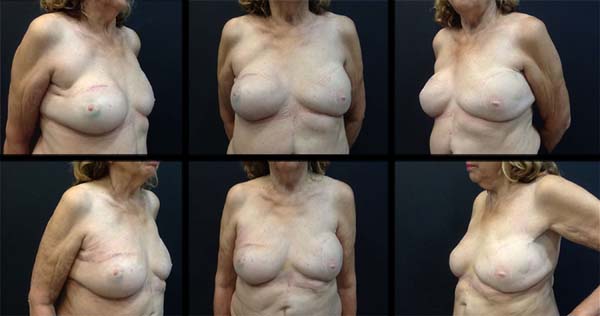

by a 332 mL prosthesis, in addition to 120 mL fat grafting in the breasts (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Clinical case no. 2.

Figure 2 - Clinical case no. 2.

Case 3: Female, 38 years old, married, underwent total mastectomy with right axillary emptying

due to tumor > 5cm and immediate reconstruction with a 450 mL expander prosthesis

in 2013, sought the service for breast symmetrization. Personal morbid history: radiotherapy

and neoadjuvant chemotherapy in May 2013. In 2015, the expanders were replaced by

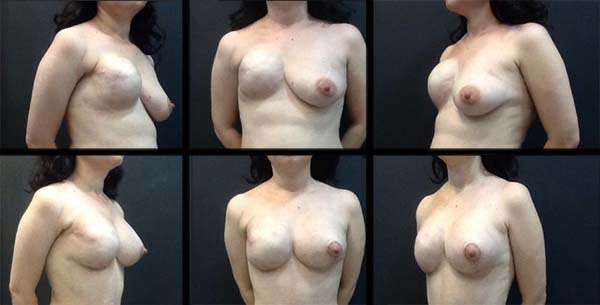

silicone prosthesis of 495 mL on the right and 250 mL on the left breast (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Clinical case no. 3.

Figure 3 - Clinical case no. 3.

DISCUSSION

The ideal augmentation material requires certain qualities, including biocompatibility,

lack of toxicity, produces consistent and reproducible results, and is cost-effective.

Autologous fat grafts have many of these qualities and also provide a natural feeling,

can be personalized for each patient and easily removed in case of complications or

dissatisfaction. The biggest challenge in autologous fat transfer is to maintain the

longevity and durability of fat grafts. This is related to the fat collection and

preparation techniques. Although there are some clinical studies on this subject,

some important questions have not been answered: (1) Can any current fat grafting

method be considered standard?; (2) Is there a more viable and functional fat preparation

method?; and, (3) Can a common fat collection and preparation protocol be found in

the light of current information in the literature?

In 20072, Coleman et al. questioned a restriction on the use of fat grafting issued by a committee

of American experts in 1987, stating that calcifications and liponecrosis observed

after fat grafting procedures are also observed in other breast procedures, such as

breast reduction and mastopexy.

Many preparation techniques have been suggested in the literature to maintain the

viability of fat grafts after being harvested and processed.

A survey by the American Society for Aesthetic Plastic Surgery reports that Coleman’s

microcannula technique is the most common method of autologous fat collection (54%),

followed by standard liposuction cannula (25%), syringe and large needle caliber (16%),

and direct excision techniques (5%). The same survey found that, after collecting

fat, 47% of respondents perform fat centrifugation, 29% perform fat washing, 12% cite

“other” unspecified treatment techniques, and 12% use no preparation method12.

Other fat collection and processing methods have been reported in the literature and

used clinically for structural fat grafting. Har-Shai et al., in 199913, used an integrated approach in which the fat grafts were harvested with a syringe

and centrifuged at 1,000 rpm. After centrifuging, the aspirate was suspended in an

enriched cell culture medium to increase the survival of autologous fat grafts. They

used this integrated technique in 15 patients and reported that the amount of graft

absorbed varied between 50% and 90% over a follow-up period of between six and 24

months12,14.

Pu et al., in 200815, reported a modified technique that included low-pressure fat aspiration using a

20 mL syringe and separation of adipose tissues using gravity without centrifugation.

Additionally, they refined fat packs with gauze and cotton sticks to remove the greasy

and non-greasy components. Although they reported that a good volume of fat was maintained

in a long-term follow-up, it is important to avoid exposing fat grafts to air to maximize

graft viability and minimize contamination.

They also compared their collection technique with conventional liposuction and showed

that low-pressure fat collection using a syringe produces more adipocytes with optimal

cellular function than the negative pressures greater than 20 cm H2O generated by conventional liposuction. However, there are no comparative studies12,13.

As for use, fat grafting in the chest wall and breast deformities is expanding rapidly.

They seem to represent a significant advance in the treatment of Poland’s syndrome

and will probably revolutionize the treatment of severe cases, producing unparalleled

quality reconstruction with short and straightforward postoperative care and less

scarring5.

This same reasoning is used for grafts in tissue that underwent radiotherapy, in which

vascularization is scarce and, even so, presents good results. Most of the studies

report a high number of complications, with fatty necrosis and images related to it

being the most frequent complication in the radiological follow-up of the grafted

area11.

The percentage of patients requiring another fat grafting session showed no significant

differences between groups. So far, clinical outcomes, fat necrosis in breast ultrasound,

and the need for new fat grafts have demonstrated that fat enriched in platelet-rich

plasma is not superior to fat grafting alone11.

Some positive effects of platelet-rich plasma in angiogenesis and stem cell proliferation

derived from fat tissue have been experimentally demonstrated. As for angiogenesis,

platelet-rich plasma growth factors stimulate endothelial cells around the injection

site, favoring the proliferation and formation of new capillaries. Besides, an in vitro study reported that plasma is a potential contributor in initiating the angiogenesis

process, recruiting endothelial cells that line blood vessels and initiating bone

regeneration13,15,16,17.

As for cell proliferation, activated platelet-rich plasma contains large amounts of

PDGF-AB and TGF-β1 and promoted the proliferation of human stem cells derived from

fat tissue and human dermal fibroblasts in vitro. Cell proliferation was maximum when 5% activated platelet-rich plasma was added

to the culture medium. Paradoxically, the addition of 20% activated platelet-rich

plasma did not show the same results15,16,17.

Lipofilling procedures can modify radiological imaging. However, their interference

has been studied in the literature, and radiological studies suggest that imaging

technologies (ultrasound, mammography, and magnetic resonance imaging) can identify

microcalcifications caused by fat injections. Also, recent follow-up studies have

demonstrated the safety of the procedure, with no increased rates of a new disease

or tumor recurrence being reported18,19.

Oncological follow-ups showed no increased risk of local recurrence after mastectomy

or conservative treatment. The clinical impression seems to suggest the opposite,

but to confirm this, more complex oncological studies comparing populations treated

with reference populations with the same oncological status are necessary5,18,19.

The volume of grafted fat was stable after three to four months and remained constant.

If a patient loses weight, the volume of transferred fat decreases, and the resulting

smaller breast size can lead to asymmetry. Therefore, it is important for patients

to understand the need to maintain a stable weight. Contrastingly, if a patient gains

weight, breast volume increases due to the increased fat deposits.

Reabsorption seemed to be less intense (between 20 to 30%) when a second session was

needed to obtain sufficient volume. This reduced-fat reabsorption rate has been clinically

evaluated. In some cases in which the patients required a second fat transfer session,

an interferometric evaluation objectively confirmed this clinical impression.

Latissimus dorsi flaps have gradually replaced TRAM flaps in the last ten years due

to more straightforward postoperative care and better use of local thoracic tissue,

avoiding a patch effect on the breast. However, in some cases, if the patient is very

thin or if there is severe flap atrophy, the reconstructed breast can be very small.

Autologous latissimus dorsal flap is the most suitable tissue to receive a fat transfer,

as it is very well vascularized, and large amounts of fat can be injected. In the

early stages of this experiment, moderate amounts (100 to 120 mL) were injected but

due to the reabsorption rate, this quantity was not enough. Lipomodelling made it

possible to correct localized abnormalities or defects in the neckline6.

Some techniques to evaluate breast volume are described in the literature for historical

purposes, and others are modern, practical, and reliable.

1. Anthropometric method

Based on end-to-end measurements, the female breast is geometrically visualized as

a half ellipse, and its volume can be calculated using mathematical formulas. Measurements

can be performed using photographs or mammograms. It is a practical technique, but

it depends on the proficiency of the examiner20.

2. The Grossman-Roudner measuring device

It is a circular plastic device with a cut along the radius line. It proved to be

practical and very profitable, as the cost of time and material total only 1.00 USD.

Although it has been used for anthropomorphic measurements of the breast in 50 women,

there is no precise validation for this method20.

3. Archimedes’ principle

A simple method of historical value based on the Archimedes’ principle of water displacement20.

4. 3D surface image

The use of 3D imaging devices provides a virtual 3D model of a standing patient that

facilitates the elimination of breast tissue compression. It simulates the post-augmentation

status and can help patients to define their desired augmentation volume. It is a

noninvasive method, and data collection does not depend on the examiner when it is

based on standardized protocols. Since magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is considered

the gold standard for non-contact volume measurements, the validity of the 3D image

was compared to MR measurements20.

5. Volume measurement with nuclear MR

Based on a high sensitivity to detect complications in autologous fat transplantation,

such as oil cysts, calcifications, or necrosis, MRI has great importance after autologous

fat transplantation to the breast. MRI is already considered the gold standard in

detecting other breast pathologies such as implant ruptures, and its use in breast

imaging is increasing. However, in addition to qualitative assessment, MRI scans of

the breast can also be used for quantitative assessment20.

RESULTS

Case 1. After six years of primary breast reconstruction, the patient presented with a bilateral

capsular contracture due to post-adjuvant radiotherapy classified as Baker 3. New

332 mL and 350 mL prostheses were placed on the right and left breasts, respectively,

with fat grafting of 80 mL on the right and 60 mL on the left breasts, showing a good

breast envelope. After two months, new fat grafting improved the breast contour and

corrected the minor deformities. The patient progressed with good surgical acceptance,

and an ultrasound follow-up showed no changes resulting from the procedure (Figure 1).

Case 2. Elderly woman who had late breast reconstruction on the right with an ipsilateral

rectus abdominis muscle flap. She was dissatisfied with the result obtained due to

asymmetry between the breasts. The prosthesis was replaced by a 350 mL expander. After

six months, this expander was replaced by an anatomical silicone prosthesis of the

same volume and a 332 mL prosthesis with the same profile was placed in the left breast.

Fat grafting of 120 mL was used to correct small asymmetries and residual deformities.

Edema, pain and mild initial hyperemia disappeared after 15 to 30 days. The patient

was satisfied with the result obtained and presented no complications during outpatient

follow-up (Figure 2).

Case 3. Young patient who underwent immediate breast reconstruction with a 450 mL expander

prosthesis. After the end of adjuvant treatment with radiotherapy, the expander was

replaced by a 495 mL silicone prosthesis in the right breast, and a 250 mL was placed

in the left breast, with preoperative breast fat grafting for edge refinement and

creation of a new nipple-areolar complex (Figure 3).

CONCLUSION

Fat grafting is a noninvasive, safe, simple, and effective procedure. It has an excellent

indication in breast reconstruction for post-reconstruction refinements and secondary

contour defects. It is also used to improve tissue quality in irradiated breasts and

to replace the total volume of the breast, as seen in recent studies6,18,19.

Breast volume measurement after fat grafting is essential for long-term follow-up.

Most of the methods discussed in this review were presented in older publications,

including the anthropometric method, the thermoplastic models, and the Archimedes’

water displacement principle. These are outdated methods compared to the most modern

and reliable volume measurement techniques, such as MR and 3D body surface scanning20.

Although studies on fat grafting procedures in the last 15 years were successful,

no Level I or II data has yet justified the recommendation of a consensual protocol

for clinical practice2,5,8,9,11,12,14,18.

In the reported cases, fat grafting associated with breast expanders and prostheses

obtained satisfactory results for the patient and surgical team. It was used to increase

breast volume, improve the skin and support tissue structure, as well as refine and

correct minor imperfections after surgery.

COLLABORATIONS

|

CCO

|

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conceptualization, Data Curation, Final manuscript

approval, Formal Analysis, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Project Administration,

Realization of operations and/or trials, Resources, Validation, Writing - Original

Draft Preparation, Writing - Review & Editing

|

|

CCS

|

Conception and design study, Supervision

|

REFERENCES

1. Pereira Filho O, Ely JB. Lipoenxertia mamária seletiva. Arq Catarin Med. 2012;41(Supl

1).

2. Coleman SR, Saboeiro AP. Fat grafting to the breast revisited: safety and efficacy.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(3):75-85.

3. Weichman KE, Broer PN, Tanna N, Wilson SC, Allan A, Levine JP, et al. The role of

autologous fat grafting in secondary microsurgical breast reconstruction. Ann Plast

Surg. 2013;71(1):24-30.

4. Costantini M, Cipriani A, Belli P, Bufi E, Fubelli R, Visconti G, et al. Radiological

findings in mammary autologous fat injections: a multi-technique evaluation. Clin

Radiol. 2013;68(1):27-33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2012.05.009

5. Delay E, Garson S, Tousson G, Sinna R. Fat injection to the breast: technique, results,

and indications based on 880 procedures over 10 years. Aesthet Surg J. 2009;29(5):360-76.

6. Gardani M, Bertozzi N, Grieco MP, Pesce M, Simonacci F, Santi PL, et al. Breast reconstruction

with anatomical implants: a review of indications and techniques based on current

literature. Ann Med Surg. 2017;21:96-104.

7. Strong AL, et al. The current state of fat grafting: a review of harvesting, processing,

and injection techniques. Plast Reconst Surg. 2015;136(4):897-912.

8. Illouz YG. Body contouring by lipolysis: a 5-year experience with over 3000 cases.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;72:591-7.

9. Fournier PF. Fat grafting: my technique. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26(12):1117-28.

10. Illouz YG. Surgical remodeling of the silhouette by aspiration lipolysis or selective

lipectomy. Aesthet Plast Surg. 1985;9(1):7-21.

11. Carvajal J, Patiña JH. Mammographic findings after breast augmentation with autologous

fat injection. Aesthet Surg J. 2008;28(2):153-62.

12. Blumenschein AR, Freitas-Junior R, Tuffanin AT, Blumenschein DI. Lipoenxertia nas

mamas: procedimento consagrado ou experimental?. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012;27(4):616-22.

13. Har-Shai Y, Lindenbaum ES, Gamliel-Lazarovich A, Beach D, Hirshowitz B. An integrated

approach for increasing the survival of autologous fat grafts in the treatment of

contour defects. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(4):945-54.

14. Özkaya Ö, Egemen O, Barutça SA, Akan M. Long-term clinical outcomes of fat grafting

by low- pressure aspiration and slow centrifugation (Lopasce technique) for different

indications. J Plast Surg Hand Surg. 2013;47(5):394-8.

15. Pu LLQ, Coleman SR, Cui X, Ferguson Junior RE, Vasconez HC, et al. Autologous fat

grafts harvested and refined by the Coleman technique: a comparative study. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(3):932-7.

16. Salgarello M, Visconti G, Rusciani A. Breast fat grafting with platelet-rich plasma:

a comparative clinical study and current state of the art. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(6):2176-85.

17. Herold C, Ueberreiter K, Busche MN, Vogt PM. Autologous fat transplantation: volumetric

tools for estimation of volume survival. A systematic review. Aesthet Plast Surg.

2013;37(2):380-7.

18. Kakudo N, Kushida S, Minakata T, Suzuki K, Kusomoto K. Platelet-rich plasma promotes

epithelialization and angiogenesis in a splitthickness skin graft donor site. Med

Mol Morphol. 2011;44(4):233-6.

19. Eppley BL, Woodell JE, Higgins J. Platelet quantification and growth factor analysis

from platelet-rich plasma: implications for wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(6):1502-8.

20. Gentile P, Scioli MG, Orlandi A, Cervelli V. Breast reconstruction with enhanced stromal

vascular fraction fat grafting: what is the best method?. Plast Reconstr Surg Global

Open. 2015;3(6):e406.

1. Hospital Geral de Fortaleza, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil.

2. Instituto do Câncer do Ceará, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Carlos Cunha Oliveira Ávila Goulart, 900, Papicu, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil. Zip Code: 60175-295. E-mail: carloscunhaoliveira@hotmail.com

Article received: December 2, 2018.

Article accepted: October 20, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.