INTRODUCTION

Breast augmentation with a silicone implant is one of the most common plastic surgery

procedures in Brazil and worldwide1-3. Considering that some of these patients may need some type of secondary intervention4-7, ranging from minor scar-repairing procedures to complex surgeries for complete breast

reconstruction, it is important for plastic surgeons to be prepared to meet patient

expectations and deal with possible difficulties.

Over the last decades, the rate of reoperations for breast augmentation has remained

unchanged at about 20% after 3 years regardless of the type of implant8.

Therefore, it is important to know different secondary surgical methods in order to

provide solutions for complex cases, inadequate results, and patients dissatisfied

with primary surgery results.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this study was to evaluate patients with previous silicone implantations

undergoing secondary mammaplasty, presenting an alternative approach with en block

resection of breast tissue, fibrous capsule, and silicone implant, followed by implant

repositioning in the partial retropectoral pocket.

Methods

This was a cross-sectional retrospective study to analyze medical records and photographic

documentation of patients who had undergone a primary breast implant surgery at least

6 months before the secondary breast surgery in the period from January 2013 to March

2017. All patients were operated by the author in his private clinic.

The analysis followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2000) and resolution

466/2012 of the National Health Council regarding ethical and legal aspects of research

involving human beings in Brazil.

This study included 24 cases of breast surgery with en block resection and implant

replacement and repositioning in the partial retropectoral pocket during the abovementioned

period.

The patients were operated by the same professional, regardless of where the primary

intervention was conducted. After an initial consultation with general evaluation

and surgical planning, the patients underwent clinical and cardiological evaluation

and were considered fit for the procedure.

The patients underwent laboratory screening, chest radiographic examinations, and

breast imaging exams. According to age and need for diagnostic clarification, some

patients underwent breast ultrasound, mammography, and/or nuclear magnetic resonance

imaging. Patients had a consultation preferably one day before surgery for photographic

documentation and clarification of any questions.

The surgery indication was based on the presence of at least one of the following

criteria: patient’s motivation to improve breast esthetics; and changes on physical

examination and/or imaging exams that justified mammaplasty with implant replacement.

Therefore, the objectives of the surgery were defined considering, above all, the

patient’s expectations regarding breast size.

Progress and results were evaluated by comparative physical examination and using

photographic records 60 days and 6 months after the procedure at regular postoperative

consultations and considering the patients’ validation of results. Ultrasound examination

was requested for all cases 6 months after the procedure to verify proper placement

of the breast implants.

Preoperative marking

After marking the midline throughout the chest, breast markings began at point A,

bilaterally. Point A corresponded to the new position of the nipple-areola complex

(NAC), and so it was positioned on the mammary midline above the anterior projection

of the mammary fold9-12. Points A were marked strictly equidistant to the thoracic midline (TML) and to the

sternal notch to identify and correct NAC asymmetries.

Vertical lines were delimited by skin traction (medially and laterally) in relation

to a point on the mammary fold (called point X), positioned at a distance 1 to 2 cm

shorter than the distance from point A to the TML. After the vertical markings were

defined, the points corresponding to the height of the lower border of the new areola

position (called points B and C) and the future point of the junction of the vertical

incisions in the mammary fold (called points D and E) were marked.

The distances of points B and C and D and E from point A were between 3.5 and 4 cm

and 10 and 11 cm, respectively. This marking was based on overall breast characteristics

(skin, breast tissue density, base diameter, and need for projection) and size of

the implant to be used.

Next, horizontal resection lines were delimited by lines marked between points D and

E and the medial and lateral extremities of the mammary fold line. During these markings,

skin traction was very carefully applied so that points D and E were more distant

than point X from the medial and lateral borders of the inframammary fold scar, in

order to prevent over-resection and excessive tension in vertical sutures, especially

with the use of larger implants.

Subsequently, all markings were photographed (Figure 1) and the positions of the future scars were shown to the patient.

Figure 1 - Preoperative marking.

Figure 1 - Preoperative marking.

The patients underwent general anesthesia or epidural block associated with intravenous

sedation in a hospital environment, respecting the anesthetic criteria and the joint

decision of the anesthetist and the patient. Analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antibiotic

medications were used during and after surgery.

Operative technique

The patient was placed in the supine position with approximately 30° of elevation;

skin incisions on the previous marking lines and de-epidermization of the periareolar

skin were then performed (Figure 2A) for subsequent superior rotation of the NAC with the superior or superomedial pedicle13, according to the previously defined point A position or the need to adapt to breast

tissue resections and size of the new implant. En bloc resection included excess skin

and breast tissue at the lower breast pole, capsule, and implant (Figures 2B, 2C, and 2D). Microdissection needles (Colorado Type, Black & Black Surgical, Inc.) were used

for electrocautery detachment to facilitate hemostasis and the perfect separation

of the capsule and surrounding tissues.

Figure 2 - En bloc resection of the skin, breast tissue, fibrous capsule, and implant.

Figure 2 - En bloc resection of the skin, breast tissue, fibrous capsule, and implant.

After complete resection of the mammary tissue, capsule, and implant, no scar tissue

or residual capsule was left. The detached area was then exhaustively washed with

0.9% saline solution and protected with a wet compresses for subsequent hemostatic

testing when necessary.

The same procedure was performed on the contralateral breast, followed by bilateral

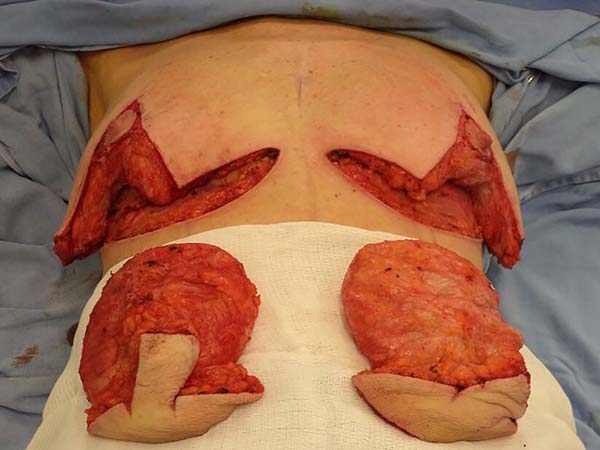

total en bloc resection of the structures (Figure 3). The capsule was opened outside the surgical field for analysis of integrity, deformities,

type, and size of the patient’s implant (Figure 4). After delimitation and symmetrization of the detached areas in both breasts, bilateral

retromuscular pockets were made starting with the incision of the pectoral muscle

in the nearest portion of the mammary fold3,7 (Figure 5).

Figure 3 - Bilateral resection.

Figure 3 - Bilateral resection.

Figure 4 - Separation of implants and breast tissue.

Figure 4 - Separation of implants and breast tissue.

Figure 5 - Incision in the pectoralis major muscle to prepare a retromuscular pocket.

Figure 5 - Incision in the pectoralis major muscle to prepare a retromuscular pocket.

After detachment of the pectoralis major muscle up to the medial insertion limit -

as necessary to accommodate the new implant and to avoid superior displacement due

to pressure resulting from muscular action - hemostasis was rigorously tested in the

anterior and posterior regions of the muscle, bilaterally.

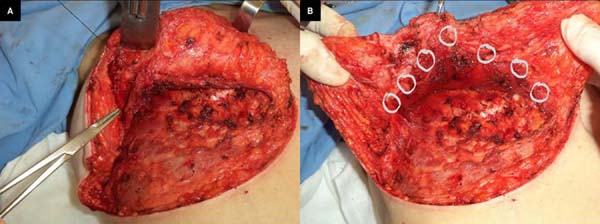

The pectoral muscle was sutured to the breast tissue to facilitate implant accommodation

in the retromuscular pocket, avoiding migration of the implant to the anterior part

of the muscle and providing muscle flap stability to the breast tissue. Suturing was

started with a stitch on the mammary midline corresponding to the point of support

at the level of the 4th or 5th intercostal space and NAC projection (Figure 6A). After that, two to four stitches were made on each side along the lower border

of the pectoralis major muscle using Mononylon® 3.0 and inverted knot sutures so that the thread was not in direct contact with the

silicone implant (Figure 6B).

Figure 6 - Suture of the pectoral muscle and breast tissue.

Figure 6 - Suture of the pectoral muscle and breast tissue.

After the implant (textured, round, high or super high profile, Eurosilicone, Mentor

Corporation, or Natrelle brands) was accommodated in a partial retromuscular pocket,

mammary suture was started at the junction of the pillars at the X-point projection,

respecting anatomical planes and perfect accommodation of mammary, subdermal, and

dermal tissue (Figure 7).

Figure 7 - Plane suture restructuring of the breast on the implant.

Figure 7 - Plane suture restructuring of the breast on the implant.

Closed suction drains were used for 1 to 5 days, depending on the volume and appearance

of the drained fluid. The drains were placed in the submuscular pocket with some holes

in the inferior lateral portion of the breast (Figure 8B). Right after surgery, it was possible to see adequate mammary tissue coaptation

with the implant and greater breast support compared to those preoperatively (Figures 8A and 8B).

Figure 8 - Immediate result.

Figure 8 - Immediate result.

All patients received verbal and written instructions on specific postoperative care

in order to avoid implant displacement, especially in the first 60 postoperative days.

RESULTS

The mean age of the operated patients was 50 years (minimum 24 and maximum 73 years)

and the mean time since the first implant surgery was 10.1 years (minimum 1 year and

maximum 25 years).

This study included 24 secondary mammaplasty procedures involving mammary implant

replacement and repositioning in the partial retropectoral pocket during the study

period. All cases presented breast changes on physical examination, including breast

ptosis (moderate to severe), capsular contracture, improper implant positioning, and

breast asymmetries.

Dissatisfaction with the results of the primary surgery was reported in 10 (41.6%)

cases, and most of these patients had undergone breast augmentation mammaplasty less

than 10 years before. The other 14 (58.4%) patients reported being satisfied with

primary surgery results; however, the changes that appeared over time motivated them

to undergo a new surgery.

Implant-related changes in image examinations (mammography, ultrasound, and/or nuclear

magnetic resonance) were described in 7 (29.1%) cases. Capsular contracture (Baker

Classification II14 or above) was identified during physical examination and in imaging exams in 7 (29.1%)

cases, and 2 (8.3%) cases showed evidence of intracapsular implant rupture. Six (25%)

primary breast augmentation procedures were performed by the author and 18 (75%) by

other professionals.

Of the cases in which the patient’s clinical history was not available, the implant

volume was accurately reported or some type of implant documentation was maintained

in only 4 (22.2%). Thus, implants with volumes different than those reported by patients

were found in 14 cases, corresponding to 77.7% of surgeries. Implant volume could

not be identified in one case because the patient had no relevant information on volume

and it was a ruptured smooth implant. It was the oldest implant (25 years) analyzed.

During surgery, textured implants were identified in 16 (66.6%) patients, polyurethane-coated

implants in 7 (29.1%), and smooth implants in 1 (4.1%).

The mean volume of the implants replaced during surgery was 233 cc (minimum 135 cc

and maximum 300 cc) on the right side and 235 cc (minimum 135 cc and maximum 375 cc)

on the left side. The mean volume of the implants repositioned during surgery was

341 cc (minimum 200 cc and maximum 450 cc) on the right side and 341 cc (minimum 220

cc and maximum 450 cc) on the left side. The mean volume of the implants used was

the same for both sides, although different sized implants were used to compensate

for asymmetries that could not be corrected only by resecting excess skin and breast

tissue. Implant volume tends to be larger in secondary surgeries to compensate for

glandular atrophy and provide greater breast tissue support, especially when placed

in the retromuscular plane.

Table 1 shows information on patients’ complaints, medical evaluation, types of implant coating,

and volume of implants replaced and repositioned in this study.

Table 1 - Clinical information and breast implant details of the cases analyzed in the study.

| Patient |

Age |

Time |

Contracture |

Rupture |

Asymmetry |

Ptosis |

Image |

Dissatisfaction |

Others |

Type

of implant

|

Right Pre |

Right Post |

Left Pre |

Left Post |

| CF |

45 |

5 |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

Textured |

260 |

350 |

260 |

350 |

| SPP |

54 |

8 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Textured |

280 |

325 |

280 |

325 |

| TPB |

62 |

25 |

X |

X |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

Smooth |

|

280 |

|

280 |

| GP |

73 |

1 |

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

Textured |

220 |

200 |

220 |

220 |

| MDV |

52 |

9 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Textured |

240 |

325 |

240 |

325 |

| GDS |

61 |

17 |

X |

X |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

Polyurethane |

135 |

400 |

135 |

400 |

| IK |

41 |

9 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Textured |

300 |

300 |

300 |

300 |

| AS |

54 |

10 |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

X |

Polyurethane |

260 |

325 |

260 |

325 |

| FR |

38 |

10 |

X |

|

|

|

|

|

X |

Textured |

235 |

375 |

235 |

375 |

| MG |

54 |

20 |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

Textured |

260 |

375 |

260 |

375 |

| VP |

47 |

8 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Textured |

220 |

325 |

220 |

325 |

| RS |

47 |

12 |

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

X |

Textured |

175 |

375 |

175 |

375 |

| IR |

60 |

2 |

X |

|

|

|

X |

|

X |

Polyurethane |

240 |

400 |

240 |

400 |

| MFR |

24 |

4 |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

Textured |

285 |

350 |

285 |

375 |

| LRL |

57 |

12 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Textured |

230 |

350 |

230 |

350 |

| EO |

39 |

4 |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

Textured |

250 |

350 |

250 |

350 |

| AA |

46 |

15 |

X |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

Polyurethane |

140 |

450 |

140 |

450 |

| JM |

33 |

3 |

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

X |

Textured |

260 |

350 |

260 |

350 |

| BV |

58 |

13 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

|

Textured |

280 |

350 |

280 |

350 |

| CF |

70 |

17 |

X |

|

X |

|

X |

|

X |

Polyurethane |

190 |

300 |

190 |

300 |

| EA |

41 |

13 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

Polyurethane |

175 |

375 |

175 |

375 |

| IG |

51 |

10 |

X |

|

|

|

X |

X |

X |

Polyurethane |

155 |

240 |

155 |

240 |

| RO |

49 |

6 |

|

|

|

X |

|

|

X |

Textured |

300 |

310 |

375 |

265 |

| EC |

44 |

10 |

|

|

X |

X |

|

X |

X |

Textured |

285 |

420 |

255 |

420 |

Table 1 - Clinical information and breast implant details of the cases analyzed in the study.

There was no implant displacement, retroglandular migration, or breast asymmetry requiring

corrective surgery at the evaluation 60 days after the surgery, using physical examination,

photographic records, surgeon’s technical validation, and patients’ approval as parameters.

The patients had no complaints of residual excess skin at the time of this evaluation.

Mild to moderate mammary ptosis was reported in 3 (12.5%) cases, mainly related to

weight loss during the period, previous presence of stretch marks, and sagging body

skin. Additional skin resection was scheduled, without any need for direct intervention

on breast implants.

The patients underwent breast ultrasound examinations 6 months after the surgery,

which showed no implant rupture, contour irregularities, residual seroma, or other

changes related to the surgery analyzed in this study.

Surgical complications included 4 cases of unilateral suture dehiscence in the inframammary

fold, representing 8.3% of the 48 operated breasts. Partial unilateral areola necrosis

occurred in one patient, corresponding to 2.8% of the operated breasts. This specific

patient had undergone the primary procedure and two breast repair surgeries. All complications

were resolved under local anesthesia. Complete suture dehiscence, hematoma, infection,

or other major complications were not reported in the patients undergoing the procedure

described in this study.

DISCUSSion

Given the significant number of women undergoing breast augmentation or breast repositioning

surgeries with silicone implants in recent years, surgeons should find practical and

objective secondary mammaplasty solutions, providing satisfactory results to patients

and avoiding excessively long procedures or high blood loss.

In 2001, Melega et al.15 described the surgical approach for en bloc resection in cases of capsular contracture

correction through an incision on the previous scar, dissecting the fibrous capsule

with blunt scissors. This procedure was called “capsulectomy without capsulotomy”.

En bloc resection of the skin, mammary gland, fibrous capsule, and implant has multiple

benefits during a highly complex surgery such as mammaplasty associated with implant

replacement.

Some of the benefits are as follows:

a) Practical skin incisions: skin incision becomes practical with the support provided

by the implant and its fibrous capsule, often hardened by capsular contracture, allowing

precise incisions even on thin skin or with stretch marks;

b) Detachment plane control: implant stability prevents the capsule from bending during

traction, facilitating detachment of the medial, lateral, and posterior portions and

virtually eliminating the risk of capsule residues;

c) Hemostasis control: it is easier to visualize and cauterize blood vessels during

resection when the contour of the fibrous capsule is detached, keeping the operative

field clean and resulting in minimal blood loss;

d) Avoiding silicone and/or intracapsular secretion extravasation into the mammary

tissue: the risk of contamination in implant replacement surgeries is significantly

reduced without opening the capsule for implant removal. Even if the capsule is opened,

it is possible to easily aspirate the intracapsular liquid content, avoiding contact

of this content with adjacent tissues;

e) Objective mammary tissue resection and implant removal: reduced surgical time in

the initial phase of the procedure provides safer mammary restructuring, reducing

complications related to long-term surgery.

Different techniques to approach the fibrous capsule have been proposed in previous

studies15-20, many of them preserving the whole capsule or part of it, with favorable results.

However, the maintenance of fibrous tissue in contact with the implant, probably incorporating

silicone gel extravasation residues, can have disastrous consequences, especially

the occurrence of potential bacterial contamination and local infection, which would

result in implant removal15,21-24.

A broad review of the literature on capsular contracture management shows that both

capsulotomy and capsulectomy can be effective, suggesting total capsulectomy in cases

of retroglandular implant contracture25.

In 2006, Spear20 described a technique for capsular contracture correction with total or partial capsulectomy

and implant repositioning to the retropectoral plane using marionette half-mattress

sutures to obliterate the subglandular space, obtaining satisfactory results with

low risk of capsular contracture.

The complexity of the surgery and the instability of the structures mobilized in the

presented procedure evidently require preventive measures to avoid implant detachment

and migration to the retroglandular space, which would be disastrous, especially if

unilateral. Thus, we used resistant and non-absorbable thread for direct suture with

multiple stitches to achieve perfect adherence of the lower border of the pectoral

muscle to the mammary tissue.

Although implants are not completely covered by the pectoral muscle, covering the

superomedial portion of the implant provides a natural result. In addition, a careful

detachment of the lower part of the pectoral muscle and the maintenance of medial

and lateral insertions allow implant accommodation, providing greater stability and

reduced risks of postoperative displacement3,19,26 (Figures 9A-9D).

Figure 9 - Results report.

Figure 9 - Results report.

In the studied cases, the use of polyurethane-coated implants and their complete adherence

to the fibrous capsule resulted in a more practical resection even with varying degrees

of capsular contracture. Fibrous capsules of textured implants were thinner, and implant

instability due to the presence of residual seroma or pockets bigger than necessary

resulted in more difficult resection.

The complication rate corroborated the results of previous studies, even considering

the complexity of the procedure and the fact that these are secondary breast surgeries2,4,5,15,19. No interventions were required for surgical repair of residual breast ptosis, implant

displacement, or breast asymmetries during the postoperative follow-up of the studied

cases. Moreover, none of the cases presented capsular contracture until this manuscript

was prepared. The results of this study show implant stability and low long-term capsular

contracture index, even considering the relatively short follow-up period.

Proper planning and implant positioning are essential in breast augmentation surgeries.

Therefore, it is important to know different secondary or reparative surgery methods

in order to provide solutions for complex cases, inadequate results, and patients

dissatisfied with primary surgery results.

CONCLUSION

En bloc resection and implant repositioning in the partial retropectoral pocket with

sutures attaching the pectoralis major muscle to breast tissue is an alternative to

improve secondary breast surgery, providing favorable results in cases of excessive

mobility or capsular contracture in implants initially placed in the retroglandular

position.

COLLABORATIONS

|

VJC

|

Analysis and/or data interpretation, Conception and design study, Data Curation, Final

manuscript approval, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing

|

REFERENCES

1. Spear SL, Bulan EJ, Venturi ML. Breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004 Oct;114(5):73E-81E.

PMID: 15457008

2. Pitanguy I, Amorim NFG, Ferreira AV, Berger R, Análise das trocas de implantes mamários

nos últimos cinco anos na Clínica Ivo Pitanguy. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2010 Dec;25(4):668-674.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752010000400019

3. Zeitoune GC, Subpeitoral ou subglandular: qual é a melhor localização do implante

para pacientes com hipomastia?. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012;27(3):428-34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752012000300017

4. Handel N, Cordray T, Gutierrez J, Jensen JA. A long-term study of outcomes, complications,

and patient satisfaction with breast implants. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Mar;117(3):757-67.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000201457.00772.1d

5. Sperly A, Bersou Júnior A, Freitas JOG, Michalay N. Complicações com próteses mamárias.

Rev Soc Bras Cir Plást. 2000;15(3):33-46.

6. Slavin SA, Greene AK. Augmentation mammoplasty and its complications. In: Thorne CH,

editor. Grabb & Smith’s plastic surgery. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;

2007. p.575-584.

7. Tebbetts JB. Dual plane breast augmentation: Optimizing implant-soft-tissue relationships

in a wide range of breast types. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006 Dec;118(7 Suppl):81S-98S.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200612001-00012

8. Teitelbaum S. Abordagem do aumento das mamas em plano duplo. In: Aston SJ, editor.

Cirurgia Plástica Estética. Elsevier. 2011;(54):675-687.

9. Hidalgo DA, Spector JA. Mastopexy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013 Oct;132(4):642e-656e.

PMID: 24076713 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31829fe4b4

10. De Benito J, Sánchez K. Key points in mastopexy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010 Dec;34(6):711-5.

PMID: 20499062 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-010-9527-5

11. Graf R, Biggs TM. In search of better shape in mastopexy and reduction mammoplasty.

Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002 Jul;110(1):309-17;discussion:318-22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200207000-00053

12. Swanson E. A retrospective photometric study of 82 published reports of mastopexy

and breast reduction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011 Dec;128(6):1282-301. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e318230c884

13. Wada A, Millan LS, Gallafrio ST, Gemperli R, Ferreira MC. Tratamento da ptose mamária

e hipomastia utilizando técnica de mamoplastia com pedículo súpero-medial e implante

mamário. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012;27(4):576-583. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752012000400018

14. Spear SL, Baker Júnior JL. Classification of capsular contracture after prosthetic

breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995 Oct;96(5):1119-23;discussion:1124.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199510000-00018

15. Meiega JM, Amaral AB, Cunha KN. Arantes HL, Kawasak MC. A Capsulectomia sem Capsulotomia

no Tratamento das Contraturas Capsulares. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2001;16(2):37-48.

16. Handel N. Secondary mastopexy in the augmented patient: a recipe for disaster. Plast

Reconstr Surg. 2006 Dec;118(7 Suppl):152S-163S;discussion:164S-167S. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.a0000246106.85435.74

17. Young VL. Guidelines and indications for breast implant capsulectomy. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 1998 Sep;102(3):884-91;discussion:892-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199809010-00043

18. Saraiva JAC. Tratamento das contraturas nas mamoplastias de aumento retroglandulares:

implante retropeitoral com retalho capsular. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2013 Jul/Sep;28(4):607-610.

19. Tebbetts JB. “Out points” criteria for breast implant removal without replacement

and criteria to minimize reoperations following breast augmentation. Plast Reconstr

Surg. 2004 Oct;114(5):1258-62. PMID: 15457046 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000136802.91357.CF

20. Spear SL, Carter ME, Ganz JC. The correction of capsular contracture by conversion

to “dual-plane” positioning: technique and outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112(2):456-66.

PMID: 12900603 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000070987.15303.1A

21. Virden CP, Dobke MK, Stein P, Parsons CL, Frank DH. Subclinical infection of the silicone

breast implant surface as a possible cause of capsular contracture. Aesthetic Plast

Surg. 1992;16(2):173-9. PMID: 1570781 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00450610

22. Tamboto H, Vickery K, Deva AK. Subclinical (biofilm) infection causes capsular contracture

in a porcine model following augmentation mammaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010 Sep;126(3):835-42.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e3b456

23. Spear SL. Capsulotomy, capsulectomy, and implantectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92(2):323-4.

PMID: 8337283 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199308000-00018

24. Peters W, Smith D, Fornasier V, Lugowski S, Ibanez D. An outcome analysis of 100 women

after explantation of silicone gel breast implants. Ann Plast Surg. 1997 Jul;39(1):9-19.

PMID: 9229086 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000637-199707000-00002

25. Dinah W, Rohrich RJ. Revisiting the management of capsular contracture in breast augmentation:

a systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016 Mar;137(3):826-41. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000480095.23356.ae

26. Mahler D, Hauben DJ. Retromammary versus retropectoral breast augmentation: a comparative

study. Ann Plast Surg. 1982 May;8(5):370-4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000637-198205000-00003

1. Centro de Cirurgia Plástica e Bem Estar, Pato Branco, PR, Brazil.

2. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Vinicius Julio Camargo Rua Tapir 757, Centro, Pato Branco, PR, Brazil. Zip Code: 85501-032. E-mail: viniciusjcamargo@yahoo.com.br

Article received: January 12, 2019.

Article accepted: July 08, 2019.

Conflicts of interest: none.