Original Article - Year 2019 - Volume 34 -

Complications of lipoabdominoplasty without Scarpa fascia preservation versus classic abdominoplasty: a prospective blind study

Comparação entre as complicações da lipoabdominoplastia sem preservação da fáscia de Scarpa com abdominoplastia clássica: um estudo prospectivo cego

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Abdominoplasty is among the most commonly performed surgical procedures. Seroma is the most common local complication associated with abdominoplasty, with an average incidence of 10%. The highest incidence of postoperative (PO) seroma occurs on the eleventh postoperative day (POD). Abdominal ultrasound is the method of choice for diagnosing seroma after abdominoplasty. New techniques have emerged aiming to improve aesthetic results with fewer complications, such as lipoabdominoplasty described by Saldanha. However, recent anatomical studies have questioned the need for Scarpa fascia preservation recommended in the lipoabdominoplasty technique, describing that around 90% of the abdominal lymphatic system is in the subdermal plane, while the other 10% is in a deep lymphatic system near the abdominal aponeurosis. The objective is to compare the incidence of seroma in lipoabdominoplasty without Scarpa fascia preservation to that in classic abdominoplasty.

Methods: Prospective blinded cohort in which 40 consecutive patients who underwent abdominoplasty without associated liposuction (n = 20) or lipoabdominoplasty (n = 20) at the Hospital de Clínicas of Porto Alegre between April 2016 and May 2017 were analyzed. All patients underwent abdominal wall ultrasonography on the tenth POD.

Results: The incidence of seroma was 5% (n = 1) in the classic abdominoplasty group and 10% (n = 2) in the lipoabdominoplasty group, with no statistical difference.

Conclusion: These results showed no statistically significant intergroup difference in seroma development.

Keywords: Abdominoplasty; Seroma; Lipectomy; Lipodystrophy; Body contouring.

RESUMO

Introdução: Abdominoplastia é um dos procedimentos cirúrgicos estéticos mais realizados. Seroma é a complicação local mais comum associada com abdominoplastia, com uma incidência média de 10%. A maior incidência de seroma pós-operatório (PO) ocorre no décimo primeiro dia PO. Ecografia abdominal é o método de escolha para o diagnóstico de seroma após abdominoplastia. Novas técnicas surgiram ao longo dos anos na tentativa de trazer melhores resultados estéticos com menos complicações, como lipoabdominoplastia descrita por Saldanha. Porém, estudos anatômicos recentes questionam a necessidade da manutenção da fáscia de Scarpa descrita na técnica de lipoabdominoplastia, descrevendo que em torno de 90% do sistema linfático abdominal está no plano subdérmico e 10% em um sistema linfático profundo justa-aponeurose abdominal. O objetivo é comparar a incidência de seroma na lipoabdominoplastia sem preservação da fáscia de Scarpa com a abdominoplastia clássica.

Métodos: Coorte prospectiva, cega na qual serão analisados 40 pacientes consecutivos que realizaram abdominoplastia sem lipoaspiração associada (n = 20) ou lipoabdominoplastia (n = 20) no Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre entre abril de 2016 e maio de 2017. Todos foram submetidos à ecografia de parede abdominal no 10o dia PO.

Resultados: A incidência de seroma foi de 5% (n = 1) no grupo de abdominoplastia clássica e de 10% (n = 2) no grupo de lipoabdominoplastia, sem diferença estatística.

Conclusão: Estes resultados, neste grupo de pacientes, mostram que não houve diferença estatística entre os dois grupos.

Palavras-chave: Abdominoplastia; Seroma; Lipectomia; Lipodistrofia; Contorno corporal

INTRODUCTION

Abdominoplasty was the fourth most commonly performed aesthetic surgical procedure in 2014 in Brazil and worldwide according to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery1. Patients with pronounced excess skin or sagging of the abdominal aponeurotic muscle system with or without hernia or excess abdominal fat are considered suitable candidates for abdominoplasty2,3.

Seroma is the most common local complication associated with abdominoplasty, with incidence rates of 1–57% and a mean incidence of 10%4,5. The highest incidence of postoperative seroma occurs on the eleventh postoperative day, most commonly at the iliac fossa6.

Abdominal ultrasonography is the method of choice for diagnosing seroma development after abdominoplasty5. To reduce the high seroma rate in the postoperative period, some preventive measures were described: minimal skin flap manipulation, progressive tension sutures, reduced surgical time, use of drains, and use of compression garments for 30 days in the postoperative period7-8.

The most widely publicized were the dead space obliteration sutures described by Baroudi & Ferreira9 and the use of drains. However, the simultaneous use of the 2 methods does not offer any advantage; when compared, they have the same incidence of seroma10.

New techniques of aesthetic correction of the abdomen have emerged over the years in an attempt to improve aesthetic results with fewer complications, such as liposuction and lipoabdominoplasty described by Saldanha11,12. However, recent anatomical studies questioned the need for Scarpa fascia preservation recommended in the lipoabdominoplasty technique, describing that around 90% of the abdominal lymphatic system is in the subdermal plane and 10% is in a deep lymphatic system near the abdominal aponeurosis13-15.

OBJECTIVE

This study aimed to compare the incidence of seroma in lipoabdominoplasty without Scarpa fascia preservation to that in classic abdominoplasty as well as the final aesthetic result, surgery time, time required for Baroudi sutures, and postoperative complications in our service.

METHODS

This prospective study included 40 consecutive patients who underwent abdominoplasty or lipoabdominoplasty and whose data were analyzed at the Hospital de Clínicas of Porto Alegre, RS, between April 2016 and May 2017. All patients provided written informed consent. The research followed the principles of Helsinki. The inclusion criterion in the lipoabdominoplasty group was supraumbilical lipodystrophy indicated for improving body contour.

Exclusion criteria were post-bariatric status or a body mass index (BMI) above 35 kg/m2. During surgery, the time at incision, end of the surgery (time of liposuction was not computed), time of beginning of the Baroudi and the final sutures (encompassing the time of the omphaloplasty) as well as their quantity were recorded. All patients were hospitalized for 24 hours after surgery and allowed to take a bath 48 hours post-surgery. No patient received postoperative antibiotic therapy; a compressive mesh was placed in the operating room and maintained for 30 days postoperatively.

After discharge, the patients were reassessed at 13 days, 20 days, 30 days, 2 months, 3 months, and 6 months, during which times photos were taken. All patients underwent abdominal wall ultrasonography on the tenth POD, and cases in which fluid of 20 mL or more was collected were identified as having seroma. All examinations were performed by the same professional, an ultrasound expert radiologist, who was blinded to the surgical technique. The final aesthetic result will be evaluated during the follow-up visit at 6 months using photos taken on the same day by a plastic surgeon blinded to the technique performed.

During the follow-up, the medical records of these patients were analyzed for the following: age, BMI, incidence of seroma, infection, comorbidities, operative complications, smoking, time to perform the Baroudi technique, and total surgery time (excluding liposuction time in the lipoabdominoplasty group). All data were entered in an Excel table.

Descriptive evaluations were performed of the variables using SPSS version 18.0.3 at the Hospital de Clínicas of Porto Alegre. Age is shown as mean and standard deviation.. Quartile distribution was used for quantitative variables. Absolute and relative frequency were used to describe qualitative variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check the distribution of the variables and to classify them as parametric or non-parametric. Age, the only parametric variable, was analyzed by the t test. For the other variables, the Mann-Whitney test was used. Fisher’s chi-square test was used to evaluate the qualitative variables.

Surgical Technique – Classic Abdominoplasty

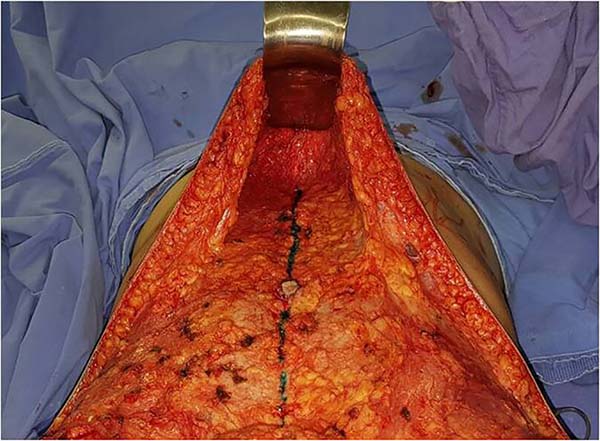

Markings were made according to the classic technique; cefazolin 2 g was administered preoperatively. An incision was made according to the upper marking to produce limited detachment up to the xiphoid process only for plication; a thin layer of loose areolar tissue near the abdominal muscle aponeurosis, the deep lymphatic tissue, was preserved13-15 (Figure 1).

In the Fowler’s position, the surplus skin was resected and the neo-navel was created using the diamond technique. Diastasis plication of the rectus abdominis muscle was performed with Prolene 0 sutures from the xiphoid process to the umbilical scar and below the umbilical scar to the pubis.

The anterior rectus abdominis aponeurosis was fixed to the umbilical scar with Mononylon 3.0 sutures. Baroudi stitches were made using Vicryl 3.0 (4 on the midline above the umbilical scar, 2 bilaterally on the upper portion of the flap). Below the umbilical scar, 4 more stitches were placed in the midline and 4 more lateral bilaterally to pull the flap to the medial position to improve the body contour. A mean 20 stitches were placed. The surgical site was closed with 3-plane Monocryl 3.0 sutures and the intradermal layer was closed with Monocryl 4.0 sutures. No drains were used. Antithrombotic prophylaxis was used in each case according to the routine service protocol.

Surgical Technique – Lipoabdominoplasty

The surgery began with liposuction and solution for infiltration (Ringer Lactate 1 L) with an ampoule of adrenaline. A mean 500 mL of fluid was infiltrated into the abdominal flap plus 250 mL for each flank when needed. Deep liposuction was performed with the machine at a pressure of 600 mmHg; final liposuction control was performed using the pinch test. Subsequently, superficial liposuction was performed in the muscle transitions to create a better body contour that favors the appearance of muscle definition. The rest of the process was performed according to the classic abdominoplasty technique. Drains were not used in any case.

RESULTS

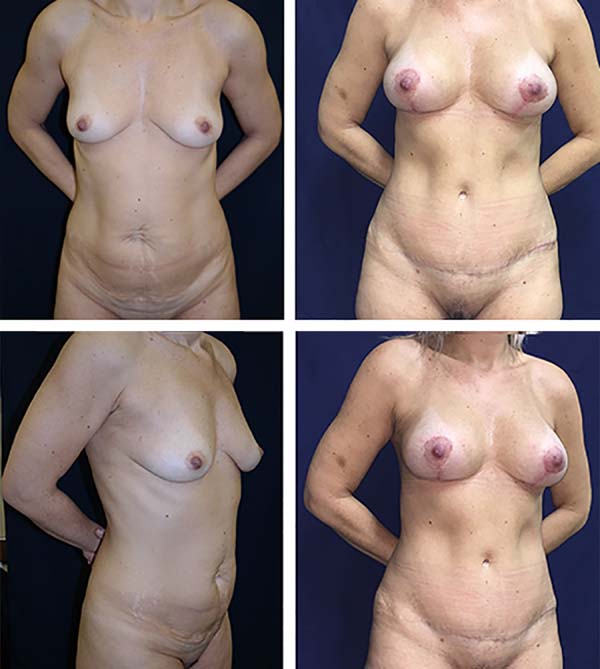

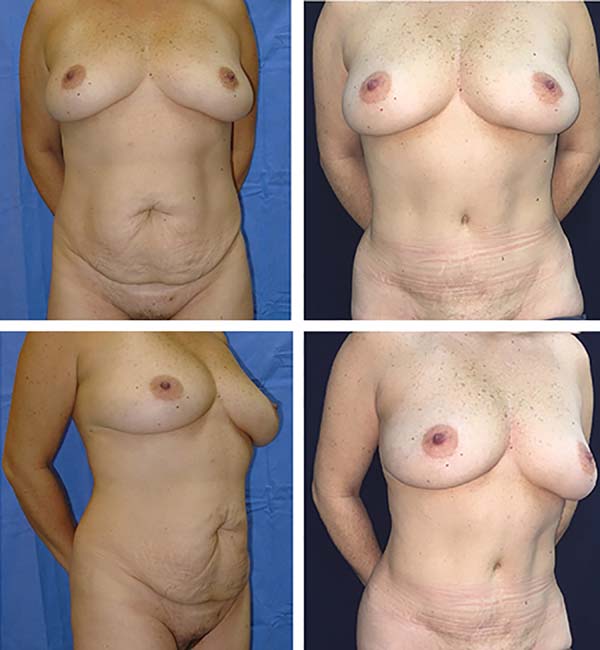

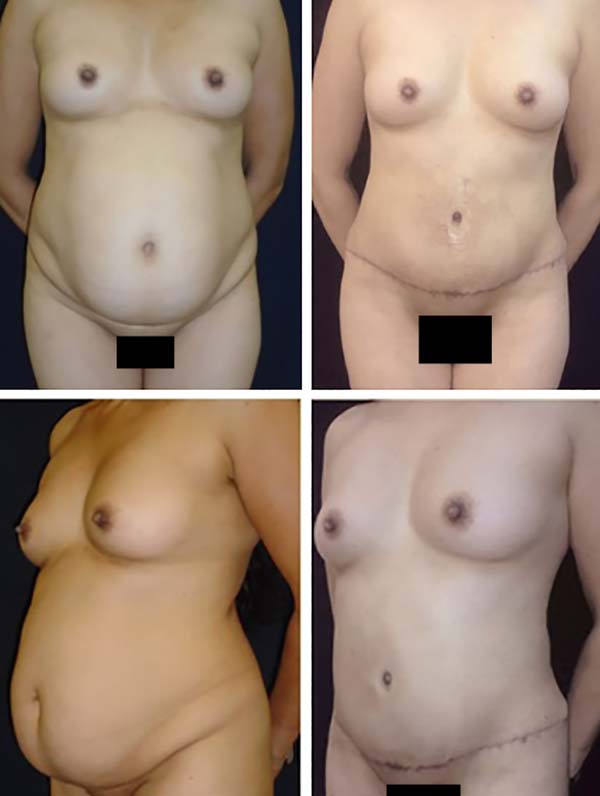

The postoperative complication rates (occurrence of seroma) were compared between groups on imaging. Of our 40 patients, 20 underwent classic abdominoplasty (Figures 2 and 3) and 20 underwent lipoabdominoplasty (Figures 4–6). All patients were female. No patient with a history of bariatric surgery or a BMI above 35 kg/m2 was included in the study. The patients’ mean age was 39.8 years, while the mean BMI was 24.3 kg/m2. Of the total number of patients, only 10% were smokers, while 17% had other comorbidities.

The classic abdominoplasty and lipoabdominoplasty groups had a homogeneous distribution in terms of the variables above; there were no significant intergroup differences. The mean ages and BMI values were 36.5 and 43.5 years and 24.16 and 24.5 kg/m2, respectively (Table 1).

| Classic abdominoplasty (n = 20) |

Lipoabdominoplasty (n = 20) |

Total (N = 40) (p > 0.05) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 36.5 | 43.5 | 39.8 |

| Mean body mass index | 24.16 | 24.5 | 24.3 |

| Smokers, % | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Other comorbidities (subarachnoid hemorrhage, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia), % | 20 | 15 | 17 |

Abdominal ultrasonography revealed that the incidence of seroma (fluid collection > 20 mL) was 5% in the classic abdominoplasty group and 10% in the lipoabdominoplasty group, with the iliac fossa being the most common site described by the radiologist. Cases of seroma were treated with needle drainage in the doctor’s office; no other procedures were needed.

The surgical wound infection incidence was 15% in the classic abdominoplasty group (versus 0% in the lipoabdominoplasty group), occurring on average on the tenth POD, with improvement after the initiation of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy and no need for another procedure.

No other postoperative complications requiring pharmacological or surgical intervention occurred during the 6-month postoperative period. The intergroup differences in the incidence of seroma or surgical wound infection were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). There were no cases of flap necrosis, hematoma, venous thromboembolism, pulmonary dysfunction, or other complications in the postoperative evaluation (Table 2).

| Classic abdominoplasty | Lipoabdominoplasty | Total (p > 0.05) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Seroma | 5% | 10% | 7% |

| Surgical wound infection | 15% | 0% | 7% |

| Hematoma | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Flap necrosis | 0% | 0% | 0% |

The plastic surgeon who evaluated the 6-month postoperative photos was blinded to which technique was used and identified better body contour in the lipoabdominoplasty group than in the classic abdominoplasty group. There was no significant intergroup difference in the number of Baroudi sutures used (mean, 20 per patient).

There was also no significant intergroup difference in time required to place the Baroudi sutures, with the average being 42 minutes per patient (including the time for omphaloplasty, which occurs between the upper and lower Baroudi sutures). There was also no difference in total surgical time, with a mean of 2 hours and 30 minutes in both groups; liposuction time in the lipoabdominoplasty group was not computed. All patients were discharged by 24 hours postoperatively.

DISCUSSION

The lipoabdominoplasty, classic abdominoplasty, and isolated liposuction techniques have been the subject of comparative studies of their efficacy, risk factors for complications, and patient satisfaction. In a prospective study comparing the 3 techniques in 2012, Swanson15 described a high satisfaction rate with all options, with the discomfort associated with classic abdominoplasty being similar to that with lipoabdominoplasty and the highest degree of satisfaction after lipoabdominoplasty.

Factors such as age, BMI, and male sex were demonstrated as isolated risk factors for major postoperative complications16,17. Associated surgeries also showed higher complication rates than isolated procedures, with a higher incidence of surgical wound infections, higher rate of deep vein thrombosis, and higher rate of postoperative pain16. These factors are responsible for a higher rate of hospital readmissions, especially in patients with previous cardiac or pulmonary comorbidities18.

To reduce the rate of seroma, the complication with the highest incidence in abdominoplasty, Baroudi & Ferreira9 described using sutures to obliterate dead space; later, Polock & Polock8 classified them as progressive tension sutures because, in addition to reducing the dead space, they reduced the tension in the surgical wound, improving the final quality of the infraumbilical scar.

In a randomized double-blind clinical trial, Andrades et al.10 compared the efficacy of progressive tension sutures with the use of drains or the combination of the 2 techniques and concluded that progressive tension sutures increase surgical time, reduce the amount of drainage, and have the same frequency of seroma incidence compared to the use of drains alone, either clinically or when evaluated by abdominal ultrasonography. The combined use of the 2 methods adds no advantage.

As an important point of lipoabdominoplasty, Saldanha advocated a more superficial flap dissection than in the classic approach that preserved the Scarpa fascia. According to Saldanha, this option allows the surgeon to keep the network of abdominal lymphatics that are predominantly below the Scarpa intact, reducing seroma rates and preventing greater bleeding since it preserves the inferior perforating vessels. In addition, Saldanha justified preservation as a way of giving more homogeneous support to the upper flap, which is naturally thinner in its caudal portion11,12.

Costa-Ferreira et al.19 published in 2013 a randomized clinical trial about the safety and efficacy of Scarpa fascia preservation. This study evidenced that Scarpa fascia preservation reduces the amount of secretion drainage by 65.5% and that drains can be removed 3 days sooner than in the group without preservation. Long periods with drain use (>6 days) were eliminated and the seroma rate was reduced by 86.7%. In addition to the results obtained, preservation of the Scarpa fascia was considered not to compromise the final aesthetic results19.

However, preservation of the Scarpa fascia has been the subject of discussion in the scientific community. Tourani et al.13 and Razzano et al.14 published anatomical studies in 2015 and 2016, respectively, questioning the need to preserve the Scarpa fascia with the objective of preserving the abdominal lymphatic system.

Tourani et al.13, based on a radiographic map of the lymphatic vessels of the abdominal wall in cadavers, described that the main lymphatic drainage medium occurs by superficial cutaneous collectors that originate in a subdermal plane in the abdomen and run superficially to the Scarpa fascia and are responsible for about 90% of the abdominal lymphatic system, while juxta-aponeurosis of the abdominal muscles in a loose areolar tissue are the deep lymphatic vessels, which are responsible for about 10% of the abdominal lymphatic system.

Razzano et al.14, through the histopathological analysis of abdominoplasty pieces, reported` findings similar to those of Tourani et al.13. Both described that there would be no need to keep all adipose tissue below the Scarpa fascia to preserve the abdominal lymphatic system.

Tourani et al.13, Razzano et al.14, and Swanson15 agreed that the most important factor in the prevention of postoperative seroma is maintaining this thin layer of loose areolar tissue, attempting to reduce dead space, and performing reduced lateral detachment of the abdominal flap. The maintenance of this juxta-aponeurotic tissue in abdominoplasties was first described by Avelar & Illouz in 198620. Therefore, preservation of the Scarpa fascia alone would not justify the reduction in the seroma rate found by Costa-Ferreira et al.19.

The results obtained here were equivalent to those in the literature. The seroma rate in the literature is 1–57%, with an average of 10% accepted by most authors6. In our analysis, both procedures provided acceptable aesthetic surgical correction of the abdomen. Classic abdominoplasty had a higher but not statistically significant rate of surgical wound infection; all cases were treated with oral antibiotics and none required reoperation. The most prevalent site of fluid collection was in the iliac fossa as reported by previous studies6.

Mean patient age was higher in the lipoabdominoplasty group, which is described in the literature as a risk factor for seroma; all other evaluated characteristics were homogeneous. In this study, age was not a decisive factor for an increase in seroma rate in the lipoabdominoplasty group, which highlights the need to evaluate a set of risk factors rather than one in isolation.

The importance of prospective studies for the analysis of complications and patient satisfaction in aesthetic procedures is well recognized15. The experience reported by the patient and the analysis of the results are more reliable and preferable in these studies15. This type of study allowed us to better evaluate the patients in the postoperative period. The importance of the same sonographer performing the analysis contributed to the greater reliability of the sample evaluated and the maintenance of a standard sonographic analysis.

The internal suture placed using the Baroudi technique allows reduction of the dead space and could be responsible for the low seroma rate21. The sum of abdominal flap dissection keeping this thin layer of loose tissue juxta-aponeurosis of the abdominal muscles with the Baroudi sutures and the use of compressive mesh for 30 days postoperatively agree with the findings of the recent systematic review conducted by Janis et al.22 on strategies for preventing postoperative seroma.

This low incidence of complications suggests that lipoabdominoplasty is as safe as abdominoplasty, not adding risk to the procedure even without Scarpa fascia preservation. However, it provides a greater aesthetic refinement in cases of supraumbilical lipodystrophy and can be performed safely using a surgical routine similar to that of classic abdominoplasty. A limitation of the study is that the total liposuction time in the lipoabdominoplasty group was not evaluated, which may have created bias in the evaluation of the general complications and seroma rates.

CONCLUSION

Our results in this group of patients show that it is possible to perform lipoabdominoplasty without Scarpa fascia preservation and maintain an incidence of seroma similar to those described in the national and international literature. Other complications did not differ significantly between the groups. There were no significant differences in recovery times. The associated liposuction allows refinement in cases of localized lipodystrophy.

COLLABORATIONS

|

JM |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, realization of operations and/ or trials, writing - original draft preparation, writing - review & editing. |

|

ACO |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conceptualization, final manuscript approval, project administration, supervision. |

|

CPP |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, project administration, writing - review & editing. |

|

MF |

Realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

MR |

Data curation, investigation. |

|

TS |

Data curation. |

|

DD |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, data curation, realization of operations and/or trials. |

|

MVMC |

Analysis and/or data interpretation, conception and design study, conceptualization, final manuscript approval, project administration, supervision, visualization |

REFERENCES

1. International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery - ISAPS. 2015 Global Statistics [acesso 2017 Nov 18]. Disponível em: https://www.isaps.org/medical-professionals/isaps-global-statistics/

2. Prado A, Andrades PR, Benitez S. Abdominoplasty: the use of polypropylene mesh to correct myoaponeurotic-layer deformity. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28(3):144-7. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00266-004-3124-4

3. Ramirez OM. Abdominoplasty and abdominal wall rehabilitation: a comprehensive approach. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(1):425-35. PMID: 10627012 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200001000-00071

4. van Uchelen JH, Werker PM, Kon M. Complications of abdominoplasty in 86 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(7):1869-73. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-200106000-00037

5. Stocchero IN. Ultrasound and seromas. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;91(1):198. PMID: 8416535 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199301000-00050

6. Di Martino M, Nahas FX, Kimura AK, Sallum N, Ferreira LM. Natural evolution of seroma in abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(4):691e-8e.

7. Baxter RA. Controlled results with abdominoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2001;25(5):357-64. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00266-001-0010-1

8. Pollock T, Pollock H. Progressive tension sutures in abdominoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31(4):583-9.

9. Baroudi R, Ferreira CA. Seroma: how to avoid it and how to treat it. Aesthet Surg J. 1998;18(6):439-41. PMID: 19328174 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1090-820X(98)70073-1

10. Andrades P, Prado A, Danilla S, Guerra C, Benitez S, Sepulveda S, et al. Progressive tension sutures in the prevention of postabdominoplasty seroma: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(4):935-46. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000253445.76991.de

11. Saldanha OR, Pinto EBS, Matos Jr. WN, Lucon RL, Magalhães F, Bello EML, et al. Lipoabdominoplastia - Técnica Saldanha. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2003;18(1):37-46.

12. Saldanha OR, Federico R, Daher PF, Malheiros AA, Carneiro PR, Azevedo SF, et al. Lipoabdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(3):934-42. PMID: 19730314 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b037e3

13. Tourani SS, Taylor GI, Ashton MW. Scarpa Fascia Preservation in Abdominoplasty: Does It Preserve the Lymphatics? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(2):258-62. PMID: 26218375 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000001407

14. Razzano S, Gathura EW, Sassoon EM, Ali R, Haywood RM, Figus A. Scarpa Fascia Preservation in Abdominoplasty: Does It Preserve the Lymphatics? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(5):898e-9e. PMID: 27119952

15. Swanson E. Prospective outcome study of 360 patients treated with liposuction, lipoabdominoplasty, and abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(4):965-78. PMID: 22183499 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e318244237f

16. Winocour J, Gupta V, Ramirez JR, Shack RB, Grotting JC, Higdon KK. Abdominoplasty: Risk Factors, Complication Rates, and Safety of Combined Procedures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5):597e-606e. PMID: 26505716

17. Hurvitz KA, Olaya WA, Nguyen A, Wells JH. Evidence-based medicine: Abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133(5):1214-21. PMID: 24776552

18. Massenburg BB, Sanati-Mehrizy P, Jablonka EM, Taub PJ. Risk Factors for Readmission and Adverse Outcomes in Abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(5):968-77. PMID: 26505701 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000001680

19. Costa-Ferreira A, Rebelo M, Silva A, Vásconez LO, Amarante J. Scarpa fascia preservation during abdominoplasty: randomized clinical study of efficacy and safety. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(3):644-51. PMID: 23446574 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31827c704b

20. Avelar J, Illouz YG. Lipoaspiração. Rio de Janeiro: Hipocrates; 1986.

21. Saldanha OR, Azevedo DM, Azevedo SFD, Ribeiro DaV, Nagassaki E, Gonçalves Junior P, et al. Lipoabdominoplastia: redução das complicações em cirurgias abdominais. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2011;26(2):275-9. PMID: 17524650 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752011000200014

22. Janis JE, Khansa L, Khansa I. Strategies for Postoperative Seroma Prevention: A Systematic Review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138(1):240-52. PMID: 27348657 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002245

1. Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto

Alegre, RS, Brazil

2. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul,

Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Corresponding author: João Maximiliano Ramiro Barcelos, nº 2350, 6ºandar - Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil Zip Code 90035-007 E-mail: jmaximilianopm@gmail.com

Article received: April 24, 2018.

Article accepted: November 11, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter