Original Article - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Ceratoacantoma: aspectos morfológicos, clínicos e cirúrgicos

Keratoacanthoma: morphological, clinical, and surgical aspects

RESUMO

Introdução: O ceratoacantoma é uma neoplasia epitelial de rápido crescimento, mais

frequente em áreas de exposição solar. Habitualmente, apresenta-se como

lesão única, arredondada, com depressão central preenchida de queratina. As

semelhanças clínicas e histopatológicas com o carcinoma de células

escamosas, frequentemente, dificultam o diagnóstico diferencial. A biópsia

excisional é a abordagem de escolha, permitindo diagnóstico e

tratamento.

Método: O presente estudo é observacional e retrospectivo, com dados de 162 pacientes

tratados de 2005 a 2013, no Hospital Felício Rocho, em Belo Horizonte, MG.

Todos os pacientes submeteram-se à excisão cirúrgica dos tumores. Foram

estudados: sexo, idade, número de lesões, localização, tamanho do tumor e

diagnóstico pré-operatório.

Resultados: Dos 162 pacientes, totalizando 173 lesões, 154 (95,06%) apresentavam

ceratoacantoma único. Noventa e dois eram do gênero masculino (56,80%) e 70

do feminino (43,20%). A idade dos pacientes variou de 11 a 96 anos, com

média de 71,23 anos. As lesões localizavam-se predominantemente nos membros

superiores (43,64%), na face (28,48%) e nos membros inferiores (17,58%). Nas

hipóteses diagnósticas formuladas pelos cirurgiões, no pedido do exame

anatomopatológico, houve diagnóstico correto em 63,13%.

Conclusão: O ceratoacantoma é uma neoplasia epitelial de características morfológicas

semelhantes ao carcinoma de células escamosas, o que, por muitas vezes,

dificulta o diagnóstico. Torna-se necessária, portanto, a excisão cirúrgica

completa das lesões suspeitas para diagnóstico e tratamento corretos.

Palavras-chave: Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Ceratoacantoma; Dermatopatias; Neoplasias cutâneas; Procedimentos cirúrgicos operatórios; Patologia cirúrgica

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Keratoacanthoma is an epithelial neoplasm of

rapid growth, more frequent in areas of sun exposure, and usually

appears as a single, rounded lesion with a central depression

filled with keratin. Clinical and histopathological similarities

with squamous cell carcinoma often make differential diagnosis

difficult. Excisional biopsy is the approach of choice, allowing

diagnosis and treatment.

Method: This is an observational and

retrospective study, in which data of 162 patients treated at the

Hospital Felício Rocho from 2005 to 2013, in Belo Horizonte,

MG, were analyzed. All patients underwent surgical excision

of tumors. Data on sex, age, number of lesions, location, tumor

size, and preoperative diagnosis were studied.

Results: Of the

162 patients, with a total of 173 lesions, only 154 (95.06%) had

keratoacanthoma. There were 92 male (56.80%) and 70 female

(43.20%) patients. The age of patients ranged from 11 to 96

years, with an average of 71.23 years. The lesions were located

predominantly in the upper limbs (43.64%), face (28.48%), and

lower limbs (17.58%). In the diagnostic hypotheses formulated

by surgeons at the request of the pathology, the diagnosis

was correct in 63.13%.

Conclusion: Keratoacanthoma is an

epithelial tumor with morphological characteristics similar to

those of squamous cell carcinoma, which often complicates the

diagnosis. Therefore, the complete excision of the suspicious

lesions is necessary for correct diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Surgical reconstructive procedures; Keratoacanthoma; Skin diseases; Skin neoplasms; Surgical procedures, operative; Pathology, surgical

INTRODUCTION

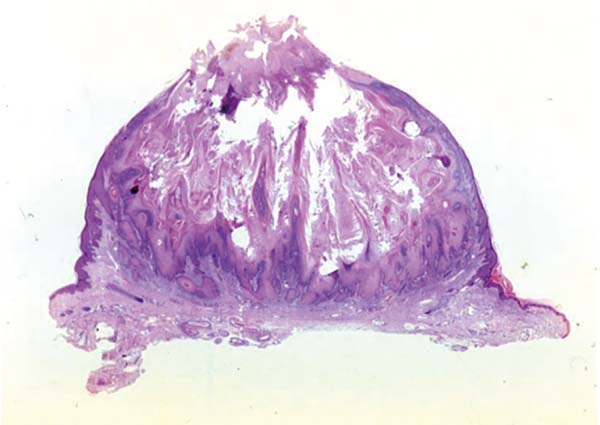

Keratoacanthoma is an epithelial neoplasm of rapid growth with clinical and histological features very similar to those of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). It was initially described by Hutchinson in 18891. Clinically, keratoacanthoma presents as a single round lesion with central depression filled with keratin1-4, which looks like a volcano (Figure 1).

Furtado (1962) described the keratoacanthoma as a lesion that starts as a painless papule, with rapid growth in a few months, followed by maturation, spontaneous involution, and cicatricial phase. The resulting scar can often be atrophic, irregular, and unsightly. Neoplasia is prone to recurrence1.

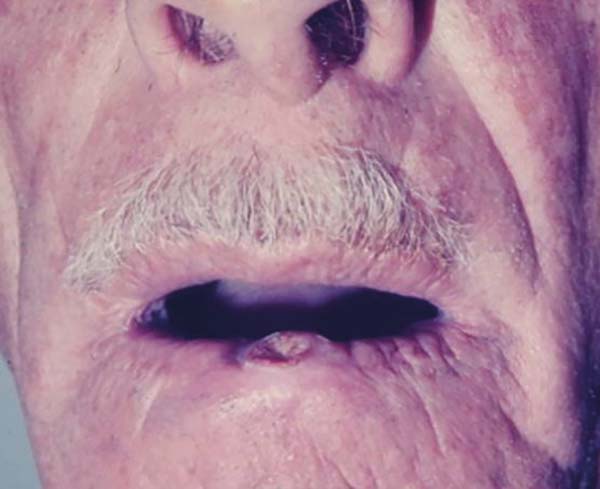

The lesions are generally found in areas of light exposure (Figure 2), especially in lighter skin that presents with other damages of solar action1-4.

Multiple lesions can arise and are associated with previous operations and trauma. They also develop in syndromes such as Fergunson-Smith and Witten-Zak2,5, where the multiple neoplasias develop by genetic inheritance2,5. There are reports of keratoacanthomas in tattoo sites, with approximately 80% associated with the red pigment6.

Keratoacanthoma has a rapid evolution, reaching its maximum size in approximately 12 weeks2. It tends to spontaneously involute, without intervention, after a period of four to six months3,4.

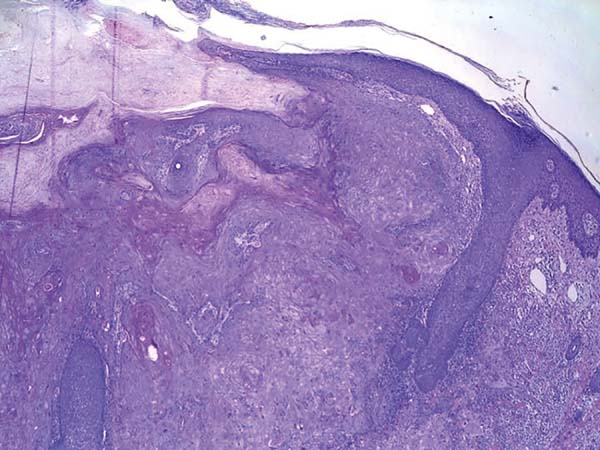

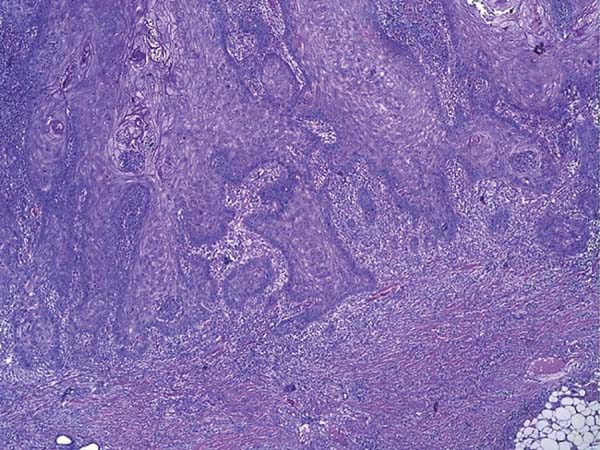

Histologically, keratoacanthoma is characterized by a crateriform structure, filled with keratin and surrounded by symmetrical epidermal horns or spurs (Figure 3). Intralesional cell proliferation presents with a majority of well-differentiated epithelial cells. Mitoses may exist mainly in the basal layer of the epidermis (Figure 4). Rarely, there is deepening of the lesion beyond the sweat glands. Often, there is associated vascular stroma, with lymphocytic, histiocytic, neutrophilic, and eosinophilic infiltration7. There is generally a well-delineated interface between the tumor and underlying subcutaneous tissue (Figure 5). There are also squamous cells presenting abundant central cytoplasm and absence of significant cellular atypia8.

In initial lesions of SCC, the histological characteristics may be similar to those of keratoacanthoma. There may be perineural invasion, deep infiltrative growth, and cellular atypia. These histological features make the clinical aspects associated with histopathology greatly important for diagnostic definition. The absence of one of these parameters may make differential diagnosis impossible7.

Immunohistochemical analyses have been studied for the differential diagnosis. A specific marker for keratoacanthoma has not yet been identified4,9.

The clinical and histopathological similarities between keratoacanthoma and SCC make differential diagnosis difficult8. Distinction between the two neoplasms is extremely important in order to establish the appropriate treatment, since SCC requires more radical operations10. If misdiagnoses are made, correct treatment may be postponed, increasing the chances of recurrence and metastases of SCC. On clinical examination, the skin surrounding the tumor is normal, and palpation does not reveal cutaneous infiltration.

Excisional biopsy is the treatment of choice for keratoacanthoma, allowing the diagnostic definition. Huge variants, such as giant keratoacanthoma (Figure 6), if not managed early, can cause significant tissue damage, making local reconstruction difficult. Although up to 50% of the cases of keratoacanthoma present spontaneous involution, this process generates atrophic and hypopigmented scars that are often unaesthetic, reinforcing the indication of early excision of the lesions2,4.

Surface incisional biopsies, curettage, and shaving are not adequate in the treatment of keratoacanthoma because it does not allow total evaluation of histological characteristics. The well-delimited interface between the tumor and underlying subcutaneous tissue is not examined, and the diagnosis may be difficult7 and sometimes impossible11.

Because of several characteristics in common with SCC, early surgical excision is also necessary to avoid a misdiagnosis, which leads to evolution of a malignant neoplasm with its complications2. Some characteristics that aid in distinguishing the lesions are well-delimited interface between tumor and underlying subcutaneous tissue, squamous cells with abundant central cytoplasm, and absence of significant cellular atypia8.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the clinical, morphological, and epidemiological characteristics of keratoacanthoma.

METHODS

The present observational and retrospective study collected data from 162 patients, corresponding to 173 keratoacanthomas, treated at Hospital Felício Rocho, Belo Horizonte, MG, from 2005 to 2013.

All patients underwent surgical excision of the tumors. Patients were divided into two groups. Group 1 consisted of 74 patients, corresponding to 81 lesions, operated at the Plastic Surgery Clinic of Hospital Felício Rocho. Group 2, composed of 88 patients, corresponding to 92 keratoacanthomas, underwent treatment at other clinics of the same hospital. Only the patients in group 1 were followed postoperatively, for at least two years.

Patients diagnosed with keratoacanthoma, based on the anatomopathological examination of the Department of Pathology of Hospital Felício Rocho, were included in this study. Patients who had the surgical specimen analyzed by the same department but underwent surgery in another institution were excluded from the study. The included reports were used as data source, aiming to determine sex, age, number of lesions, location, tumor size, and preoperative diagnosis.

In group 1, tumor recurrence as well as the appearance of new lesions compatible with the diagnosis, even in a different place far from the initial lesion, was verified.

Data were entered into Microsoft Office Excel spreadsheet, and graphics were created using SigmaPlot software version 10.0.

There were no conflicts of interest in this study, and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki revised in 2000 and resolution 196/96 of the National Health Council were followed.

RESULTS

A total of 162 patients were evaluated, with a total of 173 lesions. There were 154 patients presenting with a single keratoacanthoma (95.06%), six (3.70%) patients had two lesions, one (0.62%) had three lesions, and one (0.62%) had four lesions.

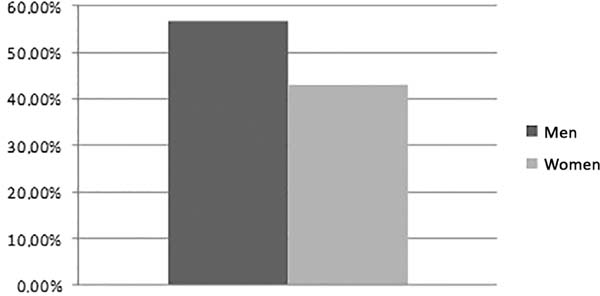

Of the 162 patients, 92 (56.80%) were male and 70 (43.20%) were female, resulting in a male/female sex ratio of 1.31 (Figure 7). The ages of the patients ranged from 11 to 96 years, with an average of 71.23 years.

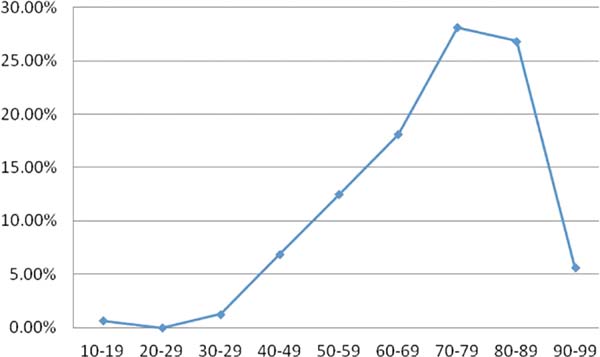

The keratoacanthomas were detected and treated predominantly in the eighth and ninth decades of life, corresponding to 55.00% of the cases (Figure 8). In two patients, the age was not mentioned.

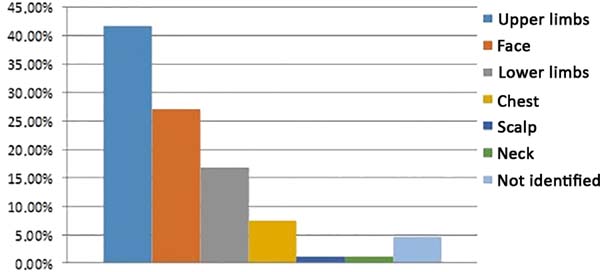

In eight patients (4.62%), the location of the lesion was not reported. Seventy-two lesions (41.62%) were located in the upper limbs, 47 (27.17%) in the face, 29 (16.76%) in the lower limbs, 13 (7.51%) in the trunk, two (1.16%) in the neck, and two (1.16%) in the scalp (Figure 9).

The lesion size ranged from 0.2 cm to 3.5 cm, with an average size of 1.07 cm.

In 13 (7.51%) requests for pathological exams, the diagnostic hypothesis was not revealed by the physician. In 101 (63.13%) of the 160 diagnostic hypotheses formulated, the surgeon made a correct diagnosis. In 59 (36.88%) cases, preoperative diagnoses were erroneous.

Of the 74 patients treated by the plastic surgery team of the Hospital Felício Rocho, no recurrence of keratoacanthoma was identified during the two-year follow-up period. Three (6.80%) patients presented with new lesions, but in a different location from that of the first lesion. One patient (1.35%) presented with a new lesion at the site of the previous keratoacanthoma 6 months after the excision, but the new lesion was diagnosed histopathologically as SCC. The first approach of this patient was performed through the “shaving” technique (superficial tangential biopsy), which was not recommended as the deep interface of the tumor was not analyzed.

DISCUSSION

Keratoacanthoma is a rapidly growing skin tumor, presenting histopathological features that are similar to those of SCC2,4. There are cases in which the differential diagnosis is controversial4,11. It is currently described as a benign tumor in the larger part of the literature2-6,8 but has already been considered a pseudomalignant lesion and even a variant of SCC4,12.

Clinically, keratoacanthoma is most often manifested as a single, nodular, round, firm lesion with a central depression filled with keratin2,3,4. At the clinical examination, in the palpation of its contour, it is perceived that the tumor does not infiltrate the adjacent skin. The skin is loose from the deep planes, and the lesion has no infiltrated or swollen margins. In this study, 95.06% of the patients studied presented single keratoacanthomas, since it is in accordance with the researched literature.

The tumor presents with rapid growth, reaching its definitive size in a few weeks3. Brenn and McKee4 described an average diameter of 1 cm to 2 cm in those lesions. Kirkham3 enlarged this average to 1 cm to 2.5 cm. These data are corroborated in the present study, which found lesions varying from 0.2 cm to 3.5 cm, with an average diameter of 1.07 cm.

The lesions are located in areas of greater exposure to ultraviolet B (UVB) radiation, in places where other signs of photoaging are already found2,13,14. According to Brenn and McKee4, up to 95% of solitary lesions develop in areas of sun exposure, with predominant appearance on the face and upper limbs. These data are reinforced by the present study, which showed 43.64% of keratoacanthomas were in the upper limbs (Figure 10), 28.48% in the face (Figure 11), 17.58% in the lower limbs, 7.88% in the trunk, 1.21% in the neck, and 1.21% on the scalp.

Keratoacanthomas are more commonly found in the men, with a male/female ratio of up to 3:14. Confirming this characteristic, data from this study showed that 92 (56.80%) patients were male and 70 (43.20%) female, resulting in a male/female sex ratio of 1.31.

The incidence of the tumor increases with age3. According to Brenn and McKee4, the majority of patients have ages in the sixth or seventh decades of life. In this work, the data found in the literature were ratified. The ages ranged from 11 to 96 years, with an average of 71.23 years. Cases in the eighth and ninth decades of life prevailed, corresponding to 55.00%.

The latter data were different from the cited literature, probably due to the change in life expectancy of the population. There are several similarities between keratoacanthoma and SCC, and it is often difficult to distinguish them only with clinical or histopathological characteristics. Kirkham3 reported that differential diagnosis was not so difficult in advanced lesions, when clinical and histopathological peculiarities are already identified. However, in early lesions, differentiation may be difficult.

In cases of diagnostic doubts, the aggressive behavior of SCC3,7 indicates that the lesions may be treated as a carcinoma, with extensive surgical excision4,7. In the present study, in 63.13% of cases, the keratoacanthoma was found in the diagnostic hypotheses formulated by the surgeons in the request of an anatomopathological analysis, and in 36.88% of cases, the hypotheses were erroneous. The data revealed that, despite the often difficult differential diagnosis, the surgeons in the study, probably due to a good knowledge of skin tumors, included the correct diagnosis in the suspected lesions.

Regarding the recurrence of keratoacanthoma, the literature data showed rates of 8%3. In the present study, 74 patients were followed during the two-year period, and 6.80% presented new lesions, but in a different location from that of the first lesion. Only one patient presented, in six months, with a new lesion at the same place as that in the previous surgical approach. It is important to note that the primary treatment, in this particular patient, had been performed by shaving, a technique not recommended for the treatment of keratoacanthoma.

The new lesion was diagnosed histopathologically as SCC, demonstrating that the differential diagnosis may be difficult and, therefore, it is necessary to follow-up the treated patients. In shaving, the entire lesion is often not resected, and differentiation with SCC becomes even more difficult as it does not allow the tumor to interface with the underlying subcutaneous tissue. In keratoacanthoma, the subcutaneous tissue is preserved. In SCC, there is an invasion in the interface of the underlying subcutaneous tissue.

CONCLUSION

Keratoacanthoma is an epithelial neoplasm with characteristics similar to those of SCC, which often makes clinical diagnosis difficult. Therefore, complete surgical excision of suspected lesions is necessary for correct diagnosis and treatment. The surgical technique of choice is excisional biopsy.

In view of the possibility of erroneous diagnosis in the usual techniques of pathology and the possibility of keratoacanthoma development in other sites, minimum follow-up of about two years is necessary.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Gil Patrus Mundim Pena for the preparation of the photomicrographs of the present study.

COLLABORATIONS

|

LN |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

JCRRA |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

EHP |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

RPLF |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript. |

|

JSAF |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

NAP |

Final approval of the manuscript; completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

RLFS |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

ACMA |

Final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

REFERENCES

1. Furtado TA. Ceratoacantoma e processos afins; estudo clínico, histopatológico e experimental [Tese]. Belo Horizonte: Faculdade de Ciências Médicas de Minas Gerais; 1962.

2. Vergilis-Kalner IJ, Kriseman Y, Goldberg LH. Keratoacanthomas: overview and comparison between Houston and minneapolis experiences. J Drugs Dermatol. 2010;9(2):117-21.

3. Kirkham N. Tumors and cysts of the epidermis. In: Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, Murphy GF, eds. Lever's histopathology of the skin. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. p. 805-51.

4. Brenn T, McKee PH. Tumors of the surface epithelium. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, ed. McKee's Pathology of the skin. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2005. p. 1153-239.

5. Brongo S, Moccia LS, Nunziata V, D'Andrea F. Keratoacantoma arising after site injection infection of cosmetic collagen filler. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4(4):429-31. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.01.012

6. Vitiello M, Echeverria B, Romanello P, Abuchar A, Kerdel F. Multiple eruptive keratoachantomas arising in a tattoo. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2010;3(7):54-5.

7. McKee P, Calonje E, Grantner SR. Pathology of the skin with clinical correlations. 3th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Mosby; 2005.

8. Tan KB, Tan SH, Aw DCW, Jaffar H, Lim TC, Lee SJ, et al. Simulators os squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: diagnostic challenges on small biopsies and clinicopathological correlation. J Skin Cancer. 2013;2013:752864.

9. Soddu S, Di Felice E, Cabras S, Castellanos ME, Atzori L, Faa G, et al. IMP-3 expression in keratoacanthoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin: an immunohistochemical study. Eur J Histochem. 2013;57(6):e6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4081/ejh.2013.e6

10. Tas E, Ugur BM, Gul A, Cinar F, Uzun L, Gun BD. A misdiagnosed keratoacantoma turned out to be a metastatic parotid carcinoma. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2010;30(2):115-7.

11. Elder DE, Elenitsas R, Johnson BL Jr, Murphy GF, eds. Lever's Histopathology of the Skin. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005.

12. Weedon DD, Malo J, Brooks D, Williamson R. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in keratoacanthoma: a neglected phenomenon in the elderly. Am J Dermatopathol. 2010;32(5):423-6. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181c4340a

13. Sazafi MS, Salina H, Asma A, Masir N, Primuharsa Putra SH. Keratoacanthoma: an unusual nasal mass. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2013;33(6):428-30.

14. Muthupalaniappen L, Das S, Md Nor N, Ali SA. Nodular Melanoma Mimicking Keratoacanthoma: Lessons to learn. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2012;12(3):360-3. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12816/0003153

1. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil.

2. Hospital Felício Rocho, Belo Horizonte, MG,

Brazil.

3. Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo

Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

4. Instituto de Cirurgia Plástica Avançada, Belo

Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

5. Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Itaúna,

MG, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Erick Horta Portugal, Rua Santa Maria de Itabira, 217, Bairro Sion, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil. Zip Code 30310-600. E-mail: erickhphp@yahoo.com.br

Article received: April 10, 2017.

Article accepted: June 22, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter