Case Report - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Reconstruction of an extensive anterior chest wall defect after mediastinitis with an omentum flap: a case report

Reconstrução de extenso defeito da parede torácica anterior pós-mediastinite com retalho de omento: relato de caso

ABSTRACT

We report the case of a 70-year-old patient who developed an extensive skin defect in the anterior chest wall after undergoing myocardial revascularization and postoperative mediastinitis. Owing to the impossibility of using cutaneous and muscular flaps on the region, we performed the reconstruction with an omentum flap based on the left gastroepiploic artery and meshed skin graft.

Keywords: Omentum; Chest wall; Surgical flap; Mediastinitis

RESUMO

Apresentamos o caso de um paciente de 70 anos de idade que evoluiu com extenso defeito cutâneo em parede torácica anterior após ter sido submetido a revascularização do miocárdio e mediastinite pós-operatória. Pela impossibilidade de utilização de retalhos cutâneos e musculares da região, fizemos a reconstrução com a rotação de retalho de omento baseado na artéria gastroepiploica esquerda e enxerto de pele em malha.

Palavras-chave: Omento; Parede torácica; Retalhos cirúrgicos; Mediastinite

INTRODUCTION

The reconstruction of extensive defects of the anterior thoracic region is a great challenge for plastic surgeons. The successful use of skin, muscle, and myocutaneous proximal flaps, as well as free and pedicled omentum flaps, for this type of repair has been described1,2.

In cases of mediastinitis after cardiac surgeries in which bleeding areas are extensive and require covering with well-vascularized tissue, the use of omentum flaps has proved to be very useful, to have wide coverage, to be safe from a circulatory viewpoint, and to be associated with less morbidity for the patient3-6.

We report an extremely severe case of mediastinitis after cardiac surgery in which the patient presented an extensive bleeding area that affected the entire anterior chest region, with poor granulation tissue and exposure of the ribs, sternum, and pericardium. We used a skin coverage with pedicled omentum flap rotation in the left gastroepiploic vessels, followed by partial meshed skin grafting in a second surgery.

CASE REPORT

A 70-year-old male patient was admitted to the hospital in September 2016. He underwent myocardial revascularization in March 2016 in another medical service center in the State of Pará. He developed operative wound infection and mediastinitis, for which he received several iterations of surgical debridement and negative pressure dressing.

He also developed an acute vascular abdomen in August 2016, that is, a few days before arriving at our hospital. According to data from the hospital where the procedure was performed, the jejunum and ileum had extensive necrosis, justifying the need to resect approximately 3 m of the small intestine, starting at 30 cm from the Treitz angle, and to consequently perform a jejunostomy procedure.

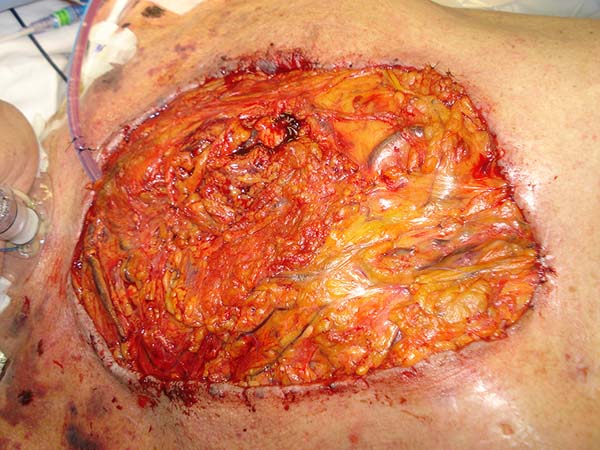

Upon arrival at our service, his general condition was poor, and vasoactive drugs were used to maintain blood pressure. He presented an extensive bleeding area in the anterior thoracic region, no visible sternum, and exposure of the pericardium, ribs, and intercostal musculature.

The cutaneous ulcer measured approximately 19 cm in width and 23 cm in length longitudinally and presented a poor granulation tissue (Figures 1 and 2). He also presented a recent middle incision in the upper abdominal wall, at a distance of 9 cm from the ulcer, and partial dehiscence. The lower right pectoral region had a recent scar in the lateroposterior direction, of approximately 14 cm long.

Along with intensive clinical care to control infection foci (lung and urine) and advanced life support, local wound care was initiated. Surgical debridement, hyperbaric oxygen therapy in a monoplace chamber, and negative pressure dressing were performed using silver foam (KCI).

Twenty days after the implementation of this therapeutic scheme and with evident improvement of the local wound conditions, the patient underwent a sternal approximation performed by the thoracic surgery team and omentum flap rotation performed using video-laparoscopy by the digestive tract surgery team. The flap generated was based on the vascular pedicle of the left gastroepiploic artery and transferred to the thoracic region by a layer of skin between the upper abdominal incision and the ulcer (Figures 3 and 4).

Moist dressings were placed daily to ensure flap hydration, and >25 days were necessary to obtain an appropriate granulation tissue, which allowed cutaneous coverage. Then, a split mesh skin graft of the right thigh was performed with an electric dermatome, with the integration of approximately 90% of the grafted area (Figure 5).

Figure 5 shows the appearance of the reconstruction site 3 weeks after the skin grafting. At the time, we were planning a new skin graft in the small residual bleeding area, the patient presented a recurrent intestinal bleeding that progressed to hemodynamic instability and irreversible cardiopulmonary arrest.

DISCUSSION

Postoperative cardiac surgery mediastinitis is a serious complication and requires a fast and multidisciplinary treatment, coordinated between the different teams involved, to reduce the high rates of morbidity and mortality. Its incidence rate is 0.5% to 4%, and the mortality rate is approximately 50% 7. For such cases, the objectives are to control infection, stabilize the chest wall, and provide a cutaneous wound coverage as soon as possible.

The plastic surgeon initially performs hygienic procedures to remove purulent collections and debridement of devitalized tissues, sparing the largest possible amount of viable tissue and visualizing the possibility of local reconstruction in the near future. The plastic surgeon is also responsible for the orientation and realization of various types of bandages, which are available in the market, among which is the negative pressure dressing, which is of great value in the treatment of complex wounds.

Where the chest wound is clean and the patient is stable, from a clinical point of view, many possibilities for reconstruction can be considered, depending primarily on the size of the defect and the conditions surrounding the ulcer8. Minor injuries can be rebuilt with local skin or fasciocutaneous flaps from nearby regions. They present less morbidity but are less reliable from a circulatory viewpoint, as they are usually pedicle flaps selected at random.

Larger, high-secretion wounds require a reconstruction with more vascularized tissues, which is more reliable from a circulatory viewpoint. In these situations, muscular and myocutaneous flaps of the major pectoralis or dorsal large muscle are the most frequently indicated.

The transfer of great omentum flaps for the reconstruction of thoracic defects has also been described and well accepted in the world literature owing to its low morbidity and high success rate.

As patients are always treated when already presenting severe conditions, all these reconstruction techniques are high-risk surgeries, and no consensus has been reached in the literature about which flap is the best option for each type of patient. We believe that each case should be well analyzed on an individual basis to choose the most suitable method.

We report a case of reconstruction of an extensive anterior thoracic defect with exposure of the pericardium and all ribs. As the wound edges were far apart, local structures could not be used. An extensive skin incision was present on the right side, and the pectoral muscles were practically absent and bilaterally retracted due to possible prior resection.

Despite a recent history of abdominal surgery to partially resect the small intestine, we opted to use the great omentum flap. Hence, we requested the assistance of colleagues from the general surgery service, who managed to assess the conditions of the great omentum by using videolaparoscopy and to make a pedicled flap on the left gastroepiploic artery, which, after passing through the subcutaneous tunnel, was enough to cover the entire bleeding area. The integration of a meshed skin graft 3 weeks after flap rotation complemented this operative strategy.

In our view, the great omentum flap proved to be a good option owing to its vascular, lymphatic, and immune properties, as well as its adhesion to the receptor site.

Its wide vascularization with extensive vessel network increases the number of possible positions. In addition, the production of angiogenic factors is great, which allows rapid neovascularization and adhesion of the repositioned tissue to the recipient area. Owing to its rich network of lymphatic tissue, which promotes good immune competence, it plays an important role in preventing local infections4.

The literature shows that using the great omentum flap can present complications at the donor site, such as abdominal hernia, small intestine obstruction, and bleeding5.

In our environment, Tavares et al.9 published their experience of using this flap in reconstructing the chest wall in 2 cases after extensive breast tumor resections. This allowed us to conclude that the procedure is effective, safe, and quite functional.

CONCLUSION

No consensus has been reached on the best type of reconstruction for extensive anterior chest wall defects; however, the great omentum flap, which was used herein, proved to be a good option in situations of great difficulty (prior recent abdominal surgery). This is due to its good blood and lymphatic vascularization and wide coverage, given its size and mobility.

Although this technique is not new, this case appeared to be a great challenge due to the extensive lesion. This study shows that the omentum flap can be used even in patients with recent abdominal surgeries for intestinal resections.

COLLABORATIONS

|

OMA |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; final approval of the manuscript; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

RGA |

Completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

DO |

Completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

CED |

Completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

PV |

Completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

FAH |

Completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

MLMA |

Conception and design of the study; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

FS |

Conception and design of the study; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

REFERENCES

1. Matros E, Disa JJ. Uncommon flaps for chest wall reconstruction. Semin Plast Surg. 2011;25(1):55-9. DOI: 10.1055/s-0031-1275171 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1275171

2. Domene CE, Volpe P, Onari P, Szachnowicz S, Birbojm I, Barreira LF, et al. Omental flap obtained by laparoscopic surgery for reconstruction of the chest wall. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8(3):215-8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00019509-199806000-00011

3. van Wingerden JJ, Lapid O, Boonstra PW, de Mol BA. Muscle flaps or omental flap in the management of deep sternal wound infection. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;13(2):179-87. DOI: 10.1510/icvts.2011.270652 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1510/icvts.2011.270652

4. Zbuchea A, Racasan O, Oprescu N. Trans-Retroperitoneal Omental Flap for Reconstruction of a LargeThoraco-Dorsal Defect, Following Oncological Resection - Case Report and Literature Review. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2016;111(2):161-4.

5. Hamid UI, Parissis H. Treatment of severe mediastinitis following cardiac surgery with omental flaps. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011. pii: bcr0320113971. DOI: 10.1136/bcr.03.2011.3971 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bcr.03.2011.3971

6. Spindler N, Etz CD, Misfeld M, Josten C, Mohr FW, Langer S. Omental flap as a salvage procedure in deep sternal wound infection. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:1077-83. DOI: 10.2147/TCRM.S134869 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/TCRM.S134869

7. Toumpoulis IK, Anagnostopoulos CE, Derose JJ Jr, Swistel DG. The impact of deep sternal wound infection on long-term survival after coronary artery bypass grafting. Chest. 2005;127(2):464-71. PMID: 15705983 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.127.2.464

8. Kaul P. Sternal reconstruction after post-sternotomy mediastinites. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;12(1):94. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13019-017-0656-7

9. Tavares FMO, Menezes CMGG, Moscozo MVA, Xavier GRS, Oliveira GM, Amorim Jr MAP, et al. Omental flap: an alternative in reconstructive surgery of chest wall. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2011;26(2):360-5.

1. Hospital 9 de Julho, São Paulo, SP,

Brazil.

2. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica, São

Paulo, SP, Brazil.

3. Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de São

Paulo, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

4. Faculdade de Medicina do ABC, Santo André, SP,

Brazil.

Corresponding author: Otavio Machado de

Almeida

Rua Barata Ribeiro, 490 Cj 51 - Bela Vista

São Paulo, SP,

Brazil Zip Code 01308-000

E-mail: omadr@terra.com.br

Article received: August 15, 2017.

Article accepted: May 17, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter