Original Article - Year 2018 - Volume 33 -

Evaluation of Max Pereira alar reconstruction technique modification in the total nasal reconstruction protocol of the Hospital of Clinics of Porto Alegre

Avaliação da modificação da técnica de reconstrução das cartilagens alares de Max Pereira no protocolo de reconstrução nasal total do Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Nasal reconstruction is the oldest plastic surgery technique. The nasal

anatomy is complex and requires an association of techniques for the

restoration of function and adequate nasal esthetics. Pereira et al.

described a technique that allows total nasal reconstruction of the alar

cartilage through the use of an auricular cartilage graft, with minimal

deformity secondary to the donor site. The objective of the present study is

to present a modification, by Collares et al., of the technique described

above, which allows the reconstruction of another anatomical region of the

nose without increasing morbidity, and its insertion into the total nasal

reconstruction protocol of Hospital de Clínicas of Porto Alegre.

Methods: A retrospective study was conducted. We evaluated technique modification in

10 patients who underwent total nasal reconstructions.

Results: After examining the 10 patients who were treated with the modified total

nasal reconstruction protocol at the Hospital de Clínicas of Porto Alegre,

we observed an improvement in the nose shape and internal nasal valve with

preservation of function, without sequelae secondary to auricular graft

removal.

Conclusion: In this case series, the modification of the Max Pereira technique resulted

in adequate aesthetic-functional treatment when implemented in the total

nasal reconstruction protocol of the Hospital de Clínicas of Porto Alegre,

without increasing the morbidity in the donor area.

Keywords: Reconstructive surgical procedures; Nasal cartilages; Nasal surgical procedures; Nose deformities, acquired; Nose neoplasms

RESUMO

Introdução: A reconstrução nasal é a mais antiga das cirurgias plásticas. A anatomia

nasal é complexa e necessita de uma associação de técnicas para a

restauração da função e estética nasal adequada. Pereira et al. descreveram

uma técnica que possibilita a reconstrução nasal total da cartilagem alar,

com o uso de um enxerto da cartilagem auricular, com mínima deformidade

auricular secundária à retirada do enxerto. O objetivo deste trabalho é

apresentar uma modificação da técnica acima descrita, que possibilita

reconstruir mais uma região anatômica do nariz, sem aumentar a morbidade,

realizada por Collares et al., e a sua inserção no protocolo de reconstrução

nasal total do Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre.

Métodos: Foi realizado um estudo retrospectivo. Avaliou-se a inserção da modificação

da técnica em 10 pacientes que realizaram reconstrução nasal total.

Resultados: Após a análise dos 10 casos, utilizando a modificação da técnica inserida no

protocolo de reconstrução nasal total do Hospital de Clínicas de Porto

Alegre, encontramos uma melhoria da forma do nariz, a válvula nasal interna

com preservação da função e sem sequelas secundárias à retirada do enxerto

auricular.

Conclusão: Nesta série de casos, a modificação da técnica de Max Pereira resultou em

tratamento estético-funcional adequado quando implementada no protocolo de

reconstrução nasal total do Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, sem

aumentar a morbidade na área doadora.

Palavras-chave: Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Cartilagens nasais; Procedimentos cirúrgicos nasais; Deformidades adquiridas nasais; Neoplasias nasais

INTRODUCTION

Nasal reconstruction is the oldest plastic surgery described. There have been reports of nasal reconstructions practiced by priests around 30 centuries before the Christian Era, and Hindi reports have described nasal reconstruction with front flap as early as 600 B.C.; more recently, Gillies, Converse, and Millard pioneered this type of surgery in the West1.

Sequelae often occur secondary to surgical treatment for nasal cutaneous tumors, especially basal cell carcinomas and epidermoids, and are the main clinical indications for nasal reconstruction. These lesions result in complex functional aesthetic defects, with stigmatizing deformities1,2. The surgical repair involves numerous technical options for cutaneous, bone, and cartilaginous reconstructions and requires a complete surgical anatomical reconstruction plan.

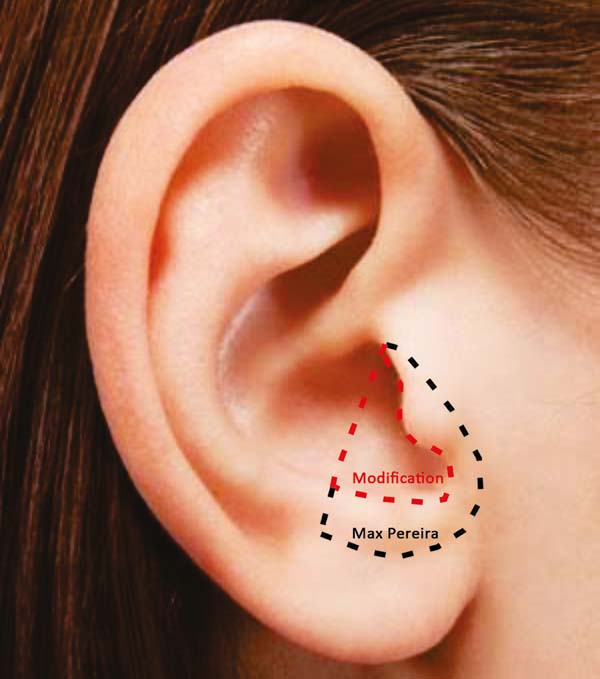

Pereira et al.3 described a technique that allows for the complete reconstruction of the alar cartilage, with almost perfect reproduction of shape and size, through the use of an auricular cartilage block graft, which includes the removal of the conch cavus, collection of the isthmus, and tragus blade. This technique relieves the use of sutures to mold the graft, making the procedure quicker, simpler, and more reliable, as it is used as a block. The donor area maintains enough cartilaginous structure to minimize secondary deformities.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this work is to present a modification of the technique of Pereira et al. This procedure was performed by Collares, and was applied in the total nasal reconstruction protocol of the Hospital de Clínicas of Porto Alegre.

METHODS

A retrospective study was carried out in which the modification of the Max Pereira technique and its insertion into the total nasal reconstruction protocol were evaluated. The treatment sequence was reviewed across 10 patients. Cartilaginous reconstruction was performed using the Max Pereira technique, modified by Collares (Figures 1 to 3).

The extension is perpendicular to the anti-helix, towards the helix branch and into the caudal direction, circumventing the auditory canal and preserving 1 mm of cartilage. The modification ends in the tragus-antitragus transition (where it will become the transition of the “neocartilage” of the lateral branch and the medial branch of the greater alar cartilage). With this extension, a block graft is obtained, which simulates a fusion of the lateral branch of the major alar cartilage with the triangular cartilage.

A lateral-to-medial incision at the transition from the lateral branch of the cartilage to the annular cartilage was performed. Due to a natural fall of the auricular shell, the segment that will replace the triangular cartilage was discretely below, and with a more closed angle with respect to the medial branch of the cartilage alar compared to the segment that will replace the lateral branch of the greater alar cartilage.

This alteration in angulation between the graft segments simulates the difference in anatomical positioning of the triangular cartilage and lateral branch of the major alar cartilage that is present in the internal nasal valve, observed during a rhinoscopy. This modification will result in a graft with more volume to structure the nose. Therefore, this graft replaces the triangular and larger alar cartilage (medial and lateral branches), providing, the anatomical reconstruction of the internal nasal valve. Furthermore, the adequate projection of the nasal tip is already obtained with the original technique.

In the 10 patients, the total nasal reconstruction protocol of the Clinical Hospital of Porto Alegre was performed. For nasal skin reconstruction, a frontal flap was made, and for reconstruction of the nasal lining and cartilage grafts, bilateral nasogenic flaps were made. Finally, to cover the bony graft, a flap of pericranium was made in somersault. Bone reconstruction was performed with a bone graft, with the partial thickness of the calvarial fixed with plate and screw in the glabella (Figure 4).

RESULTS

After analyzing the 10 sequential cases, we found an adequate nasal tip shape (Figures 5 to 8). The patients reported preserved nasal function and satisfactory internal nasal valve reconstruction without evidence of pinching at physical examination. There was no evidence or complaints of auricular deformities that occurred secondary to graft removal (Figure 9).

DISCUSSION

Anatomical nasal reconstruction is based on a favorable contrast between the nose and surrounding tissues, discrete scarring, coloration, and texture that mimics adjacent tissues and bilateral symmetry. Thus, the association of flaps and grafts, that restores the structural and functional aspects of the nose, becomes essential in total nasal reconstruction4.

Considerations regarding the size, anatomical location, and depth of the defect that result from tumor resection will influence the treatment plan. The restoration of the nasal cartilaginous bone support is fundamental for aesthetic and functional results.

Nasal projection, fibroelastic consistency, mobility, and airflow permeability are dependent on alar cartilage, and the defects in this structure have aesthetic and functional impacts. Septal, auricular, and costal cartilage grafts are the most used for this purpose, either with free or composite graft5.

Costal cartilage was successfully used in the complex nasal reconstruction described by Hafezi et al6. The authors report a case where the graft was modeled for complete reconstruction of the nasal structure, and remained without change of shape or resorption after the one-year follow-up. Even with the need for additional surgical interventions to correct shape details, the procedure was successful and recommended for patients with defects that resulted from trauma, neoplasms, and congenital anomalies.

However, there is a need for various sutures for molding, and costal cartilage grafts are likely to generate some kind of asymmetry in cartilage memory in the late postoperative period. To avoid long-term cartilage changes, it is possible to sculpt the costal cartilage using only its inner portion. However, this method eliminates the perichondrium, making it difficult to integrate the graft and increasing the chance of reabsorption.

Holmström et al.7 described the use of iliac crest bone grafts for nasal tip reconstruction. However, the inflexibility, risk of fracture, and reabsorption were the main limitations of this technique.

Peck8 described the complete replacement of bilateral cartilages, using an auricular cartilage graft and nasal septum. However, they are not block grafts, require various sutures, and weaken at some sites to shape and mimic the alar cartilages. Thus, they are more likely to move and lose shape in the immediate postoperative period during scar retraction.

Pereira et al.3 carried out an anatomical study on corpses, with the objective of evaluating and comparing the dimensions and forms of the alar cartilages with the lower structures of the auricular cartilages, which were used to perform a block resection of the tragus, isthmus, and concave cavus, to the medial crura, junction of the medial and lateral crura, and lateral crura. Despite the anatomical variations, there was similarity between all cartilages that were removed in block, which presented a similar format to the homolateral alar cartilage.

This procedure can be used for repairs of independent sections of the nasal structure, bilateral complete reconstruction of the wings, and cases of congenital deformities, in which there are deficiencies in the projection of the nasal tip. This problem is often encountered by plastic surgeons and is often observed in Binder’s syndrome9.

This technique has the advantages of a block graft without the need for stitches or weakening of the cartilage that is used for molding. This reduces the possibility of secondary deformities upon retraction in the late postoperative period, has low reabsorption rate, and the flexibility is similar to that of nasal cartilage. In addition, the shape, size, and thickness are ideal for replacing alar cartilage.

With the bilateral removal of the grafts and junction through unabsorbable points in the medial portion, we obtained a shape that was very similar to the middle and lateral crosses. Due to the stiffness and resilience of this graft, the medial structure is similar to a vertical “strut,” thus allowing the nasal projection to be maintained with a low probability of alterations in the format. In addition, this technique maintains the perichondrium, which facilitates the integration of the graft9.

Portinho et al.10 also described the use of the technique in newborn patients, proving its versatility and long-term efficiency.

In this paper, we describe a modification of the Pereira et al. technique, which seeks to restore the anatomical properties of the nose through the prolongation of resection of the shell. Our objective is to attach to the graft in block a new segment of cartilage that will replace the triangular cartilage. Through this modification, a graft with more cartilage volume is achieved, allowing a better structuring of the nasal cartilaginous reconstruction.

The incision in the lateral superior region of the graft described above aims to produce the difference between the angularities of the alar and triangular cartilages. This allows the graft to have the volume and size necessary to reconstruct another anatomical region and accompany the nasal anatomical nuances. With this extension, it is possible to anatomically reconstruct the internal nasal valve. In the literature, no technical descriptions for such a reconstruction following the treatment of deformities secondary to total rhinectomies have been reported.

The resection prolongation did not add any morbidity in the donor area nor the immediate postoperative period, nor did it result in sequels in the late postoperative period. This demonstrates that the cartilaginous remnant was sufficient to maintain the atrial cartilageous structure that was necessary to avoid deformities in this series of patients.

The insertion of the Max Pereira technique modification in the total nasal reconstruction protocol of the Hospital de Clínicas of Porto Alegre did not significantly increase the resection time of the grafts, did not alter the routines regarding the care of the donor zone, and allowed adequate reconstruction of the valves in the evaluated patients.

CONCLUSION

We describe the implementation of a modification of Max Pereira’s greatest alar cartilage reconstruction technique, which was proposed by Collares total nasal reconstruction protocol of our hospital.

COLLABORATIONS

|

MVMC |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; statistical analyses; final approval of the manuscript; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

JM |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; conception and design of the study; completion of surgeries and/or experiments; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

CPP |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data; writing the manuscript or critical review of its contents. |

|

ACPO |

Completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

MMF |

Completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

DEM |

Completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

LKR |

Completion of surgeries and/or experiments. |

|

DD |

Analysis and/or interpretation of data. |

REFERENCES

1. Souza Filho MV, Kobig RN, Barros PB, Dibe MJA, Leal PRA. Reconstrução nasal: análise de 253 casos realizados no Instituto Nacional de Câncer. Rev Bras Cancerol. 2002;48(2):239-45.

2. Senandes LS, Vizzotto MD, Fischer A, Zanol F, Lima VS. Reconstrução Nasal Complexa: Série de 10 casos. Arq Catar Med. 2014;43(1):150-4.

3. Pereira MD, Marques AF, Ishida LC, Smialowski EB, Andrews JM. Total reconstruction of the alar cartilage en bloc using the ear cartilage: a study in cadavers. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96(5):1045-52. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199510000-00006

4. Konofaos P, Alvarez S, McKinnie JE, Wallace RD. Nasal Reconstruction: A Simplified Approach Based on 419 Operated Cases. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2015;39(1):91-9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00266-014-0417-0

5. Quintas RCS, Araújo GP, Medeiros Jr JHGM, Quintas LFFM, Kitamura MAP, Cavalcanti ELF, et al. Reconstrução Nasal Complexa: Opções Cirúrgicas Numa Série de Casos. Rev Bras Cir Plast. 2013;28(2):218-22. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1983-51752013000200008

6. Hafezi F, Naghibzadeh B, Ashtiani AK, Nouhi AH, Naghibzadeh G. Total nasal skeletal reconstruction disfigured by granulomatosis with polyangitis (wegener granulomatosis). Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3(2):e308. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000000278

7. Holmström H. Surgical correction of the nose and midface in maxillonasal dysplasia (Binder's syndrome). Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78(5):568-80.

8. Peck G. Techniques in Aesthetic Rhinoplasty, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1990.

9. Pereira MD, Andrews JM, Martins DM, Marques AF, Ishida LC. Total en bloc reconstruction of the alar cartilage using autogenous ear cartilage. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(1):168-72. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00006534-199501000-00030

10. Portinho C, Collares MVM, de Castro ACB, Faller G. Early nasal reconstruction in fetal warfarin syndrome. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2008;36(Suppl 1):S193. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1010-5182(08)71890-0

1. Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto

Alegre, RS, Brazil.

2. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul,

Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil.

Corresponding author: Marcus Vinicius Martins

Collares

Rua Ramiro Barcelos, 2350, 6 andar

Porto Alegre, RS,

Brazil Zip Code 90035-903

E-mail: collares.cmf@gmail.com

Article received: September 17, 2017.

Article accepted: May 17, 2018.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter