ISSN Online: 2177-1235 | ISSN Print: 1983-5175

The impact of breast reconstruction on the quality of life of patients after mastectomy at the Plastic Surgery Service of Walter Cantídio University Hospital

Impacto da reconstrução mamária na qualidade de vida de pacientes mastectomizadas atendidas no Serviço de Cirurgia Plástica do Hospital Universitário Walter Cantídio

Original Article -

Year2013 -

Volume28 -

Issue

1

Carolina Garzon Paredes1; salustiano Gomes de Pinho Pessoa2; Diego Tomaz Teles Peixoto3; Dayanne Nogueira de Amorim3; Jéssica Silveira Araújo3; Paulo Roberto Araujo Barreto3

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION: The aim of breast reconstruction is to restore body contour and improve the patient's self-image by replacing the volume loss and ensuring proper symmetry with the contralateral breast. This study evaluated the quality of life and physical, psychological, and social aspects of patients who underwent mastectomy and immediate or delayed breast reconstruction.

METHODS: Twenty-seven patients underwent breast reconstruction at Walter Cantídio University Hospital between August 2007 and August 2012. The World Health Organization Quality of Life survey was used to conduct a cross-sectional study to evaluate patient quality of life.

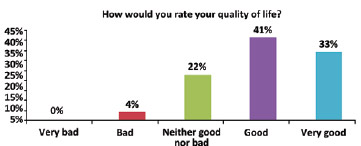

RESULTS: The patients positively evaluated their quality of life. A score of 4 (good) and 5 (very good) was assigned by 41% and 33% of women, respectively, to the question "How would you rate your quality of life?" Among the patients, 81% underwent immediate reconstruction and most (45%) assigned a score of 4 (good) to the question "How would you evaluate your quality of life?" A total of 60% of patients who underwent delayed reconstruction attributed a score of 5 (very good) to this question.

CONCLUSIONS: These results demonstrate that breast reconstruction after mastectomy results in good or very good quality of life and is associated with physical, psychological, and social benefits.

Keywords:

Quality of life. Mammaplasty. Self concept. Mastectomy.

RESUMO

INTRODUÇÃO: A reconstrução mamária tem por objetivo restabelecer a estética corporal e melhorar a autoimagem da paciente, restaurando o volume perdido e assegurando simetria com a mama contralateral. O objetivo deste trabalho é verificar a qualidade de vida de pacientes mastectomizadas e submetidas a reconstrução mamária imediata ou tardia, abordando os domínios físico, psicológico e social.

MÉTODO: Foram estudadas 27 pacientes submetidas a reconstrução mamária no Hospital Universitário Walter Cantídio, entre agosto de 2007 e agosto de 2012. Foi realizado um estudo transversal, com avaliação da qualidade de vida por meio da aplicação do questionário World Health Organization Quality of life (WHOQOL) abreviado.

RESULTADOS: As pacientes entrevistadas avaliaram positivamente sua qualidade de vida, com atribuição da nota 4 (boa) por 41% e 5 (muita boa) por 33% das entrevistadas à pergunta "Como você avaliaria sua qualidade de vida?". Dentre as pacientes entrevistadas, 81% foram submetidas a reconstrução imediata e a maioria delas (45%) atribuiu nota 4 (boa) à pergunta "Como você avaliaria sua qualidade de vida?". Por outro lado, 60% das pacientes submetidas a reconstrução tardia atribuíram nota 5 (muito boa) a essa pergunta.

CONCLUSÕES: Os resultados demonstram que a reconstrução mamária possibilita à mulher mastectomizada incorporar ao tratamento do câncer de mama conceitos de qualidade de vida, trazendo benefícios físicos, psicológicos e sociais.

Palavras-chave:

Qualidade de vida. Mamoplastia. Autoimagem. Mastectomia.

INTRODUCTION

Breast cancer is a leading cause of death among women with malignant neoplasms. It is the second most frequent cancer and is one of the main concerns among women and public health services in Brazil.

Mastectomy, one of the most effective treatments for this disease, involves partial or total removal of the breast and axillary lymph nodes in an attempt to remove the entire tumor. Although efficient, this surgical procedure induces serious body lesions because it removes organs that women consider symbols of their femininity and sexuality; this removal negatively influences their quality of life.

The aim of breast reconstruction is to restore body contour and improve the patient's self-image by replacing the volume loss and ensuring proper symmetry with the contralateral breast. The reconstruction procedures used may vary according to the surgery performed. In Brazil, breast reconstruction is performed using a rectus abdominis muscle flap (TRAM), dorsal muscle flap, or a tissue expander that is later replaced by a silicone prosthesis.

Because of the lack of studies in the literature assessing the impact of breast reconstruction on the quality of life of women after mastectomy, we decided to address this issue by comparing the quality of life between women who underwent immediate and delayed breast reconstruction. The World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) survey was used as a generic questionnaire to assess good psychometric properties in patients with breast cancer. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the quality of life as well as the physical, psychological, and social aspects of patients who underwent mastectomy followed by immediate or delayed breast reconstruction.

METHODS

Twenty-seven patients were invited to participate in this study. Breast reconstruction was performed at the Plastic Surgery Service of Walter Cantídio University Hospital (Fortaleza, CE, Brazil) between August 2007 and August 2012. These patients underwent mastectomy (radical, radical modified, or conservative) followed by immediate or delayed breast reconstruction using a latissimus dorsi muscle flap, TRAM, or a tissue expander.

This cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the patients' quality of life using the WHOQOL. This questionnaire was proposed by the WHO and validated for Brazilians and includes good criteria to evaluate patients with breast cancer. It is a self-evaluation and self-explicatory tool that consists of 26 questions referring to 5 different aspects: physical, psychological, social, environmental, and level of independence. Each question is scored as a whole number of 1-5 and each value corresponds to a response. The numbers are arranged in increasing order of positivity: 1 (very bad), 2 (bad), 3 (neither bad nor good), 4 (good), and 5 (very good).

The response to the first question ("How would you rate your quality of life?") was compared between patients who underwent immediate or delayed reconstruction.

RESULTS

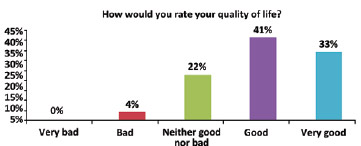

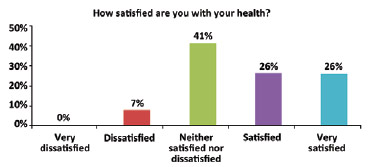

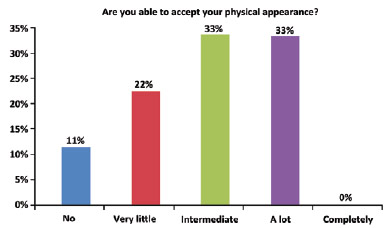

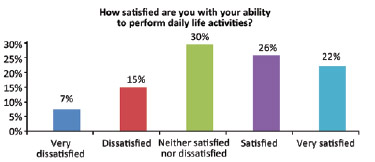

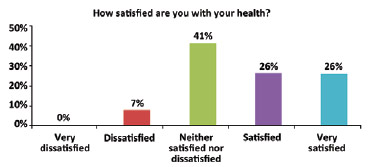

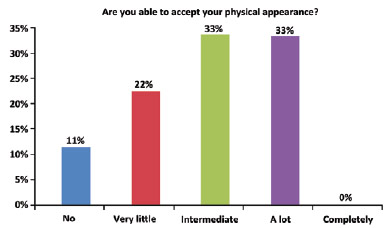

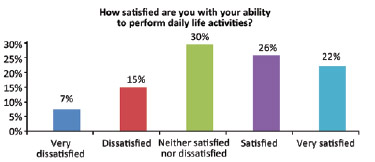

The average patient age was 44 years (range, 31-59 years). The patients positively evaluated their quality of life. The question "How would you rate your quality of life?" was scored as 4 (good) and 5 (very good) by 41% and 33% of the women, respectively (Figure 1). The average score for this question was 4.03 ± 0.85. The item "How satisfied are you with your health?" was scored as 3 (neither satisfied nor dissatisfied) by the majority (41%) of the respondents. The average score was 3.70 ± 0.95 (Figure 2). When asked whether they were able to accept their physical appearance, a score of 3 (intermediate) and 4 (very much) was assigned by 33% and 33% of the respondents, respectively. The average score was 3.88 ± 1.01 (Figure 3). A total of 30% of the interviews scored the item "How satisfied are you with your ability to perform daily life activities?" as 3 (neither satisfied nor dissatisfied) (Figure 4). The average score for this question was 3.40 ± 1.21.

Figure 1 - Subjective assessment of quality of life.

Figure 2 - Subjective assessment of health.

Figure 3 - Satisfaction with physical appearance.

Figure 4 - Subjective assessment of the ability to perform daily activities.

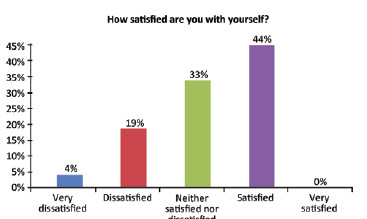

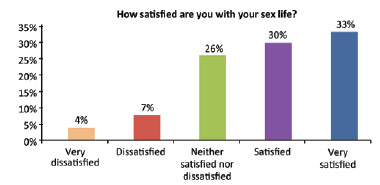

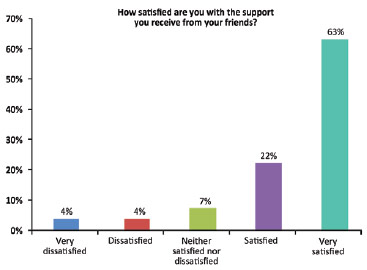

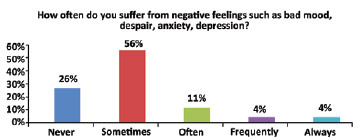

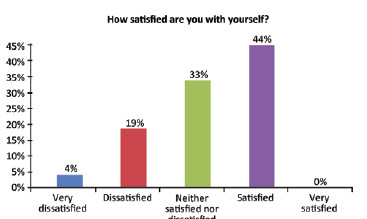

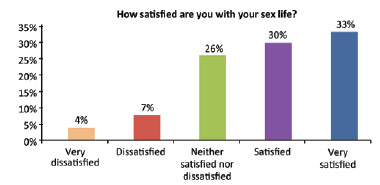

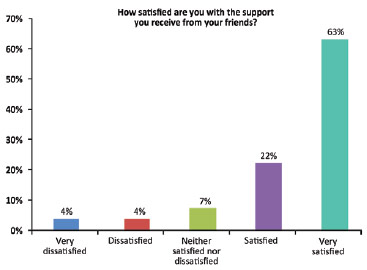

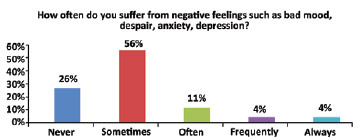

A total of 44% of the patients scored the question "How satisfied are you with yourself?" as 4 (satisfied) (average score, 4.18 ± 0.87) (Figure 5). The question "How satisfied are you with your sex life?" was scored as 5 (very satisfied) by 33% of the patients (average, 3.81 ± 1.11) (Figure 6). "How satisfied are you with the support you receive from your friends?" was scored as 5 (very satisfied) by the majority of the patients (63%; average, 4.37 ± 1.04) (Figure 7). Another important question in this survey ("How often do you suffer from negative feelings such as bad mood, despair, anxiety, depression?") was scored as 2 (sometimes) by 56% of the respondents (average, 2.18 ± 1.07) (Figure 8). A total of 81% of these patients underwent immediate reconstruction and most of them (45%) scored the item "How would you rate your quality of life?" as 4 (good). However, 60% of the patients who underwent delayed reconstruction scored this question as 5 (very good).

Figure 5 - Self-assessment of patient satisfaction.

Figure 6 - Self-assessment of sexual satisfaction.

Figure 7 - Subjective self-assessment of the support received from friends.

Figure 8 - Frequency of negative feelings.

DISCUSSION

In this study, women who underwent breast reconstruction were highly satisfied with their quality of life as well as psychological and social aspects. Moreover, most patients showed a high or very high level of satisfaction with their degree of independence, suggesting that the functional postoperative adaptation was not negatively influenced by additional anatomical changes due to the breast reconstruction. These results are in line with the findings obtained in earlier studies that addressed the psychosocial aspects of breast reconstruction after the use of other methodological approaches1-8.

When questioned about the level of satisfaction with their health, most patients scored this item as average or very high, in contrast to the low scores obtained in other studies9-11.

One of our more important findings with practical implications was the little impact that breast reconstruction had on the physical aspects and level of independence of these women. This was an expected effect because the reconstruction involved important anatomic manipulations that could result in physical discomfort and transient or permanent changes in mobility. After comparing different types of surgical procedures, several authors observed no significant changes in the physical aspects of women undergoing breast reconstruction1,12.

Most patients rated sexual satisfaction as intermediate or very high. These patients require time to restart their sexual activity because of the change in their self-image. Moreover, these patients need to adapt to their new appearance before resuming relationships with their partners.

In the literature, improved social interactions and professional satisfaction, higher levels of satisfaction, and a lower incidence of depression have been reported at 1 year after immediate reconstruction12. However, such levels of gratification are quite unusual after immediate reconstruction compared to a more conservative intervention such as quadrantectomy or lumpectomy. However, partial breast preservation may be beneficial for psychological acceptance of this treatment13-17. In this study, women who underwent delayed reconstruction were more satisfied than those who underwent immediate reconstruction, a finding that supported those of earlier studies3-5,18. This result may be attributed to the fact that patients who underwent immediate breast reconstruction compared the new breast with the previous breast and were more concerned with aesthetic perfection. In delayed breast reconstruction, patients feel relief when know that is time to reconstruct their lost breast. However, this does not justify a delay in performing breast reconstruction because the patient should not decide when the surgery is performed. The search for new methods to help a patient cope with her appearance should not replace the aims of breast reconstruction and the benefits of this operation. Reconstructive surgery is a personal decision, and only women who have or are on the verge of losing a breast may evaluate the importance of this intervention.

This study analyzed a small cohort; therefore, we cannot clarify to what extent our results can be generalized to all women undergoing breast reconstruction.

CONCLUSIONS

Breast reconstruction helps women who undergo mastectomy to improve quality of life, integrity, and self-image. Consequently, such patients experience less traumatic rehabilitation during breast cancer treatment. This association confers physical, psychological, and social benefits.

As this study demonstrated, women who underwent delayed breast reconstruction were more satisfied with the surgical outcome. These patients had more time to adapt to their experience; this facilitated the acceptance of the new breast. They also valued their new breast more highly because it represented repair of their loss and helped them regain their body image. This feeling was not shared by women who underwent immediate reconstruction, during which, the patient enters and exits the operating room with different breasts.

REFERENCES

1. Parker PA, Youssef A, Walker S, Basen-Engquist K, Cohen L, Gritz ER, et al. Short-term and long-term psychosocial adjustment and quality of life in women undergoing different surgical procedures for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(11):3078-89.

2. Den Oudsten BL, Van Heck GL, Van der Steeg AF, Roukema JA, De Vries J. The WHOQOL-100 has good psychometric properties in breast cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(2):195-205.

3. Stevens LA, McGrath MH, Druss RG, Kister SJ, Gump FE, Forde KA. The psychological impact of immediate breast reconstruction for women with early breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73(4):619-28.

4. Harcourt DM, Rumsey NJ, Ambler NR, Cawthorn SJ, Reid CD, Maddox PR, et al. The psychological effect of mastectomy with or without breast reconstruction: a prospective, multicenter study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(3):1060-8.

5. Roth RS, Lowery JC, Davis J, Wilkins EG. Quality of life and affective distress in women seeking immediate versus delayed breast reconstruction after mastectomy for breast cancer. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116(4):993-1002.

6. Wildes KA, Miller AR, Majors SS, Ramirez AG. The religiosity/spirituality of Latina breast cancer survivors and influence on health-related quality of life. Psychooncology. 2009;18(8):831-40.

7. Howsepian BA, Merluzzi TV. Religious beliefs, social support, self-efficacy and adjustment to cancer. Psychooncology. 2009;18(10):1069-79.

8. Potter S, Thomson HJ, Greenwood RJ, Hopwood P, Winters ZE. Health-related quality of life assessment after breast reconstruction. Br J Surg. 2008;96(6):613-20.

9. Anderson SG, Rodin J, Ariyan S. Treatment considerations in post-mastectomy reconstruction: their relative importance and relationship to patient satisfaction. Ann Plast Surg. 1994;33(3):263-70.

10. Nissen MJ, Swenson KK, Ritz LJ, Farrell JB, Sladek ML, Lally RM. Quality of life after breast carcinoma surgery: a comparison of three surgical procedures. Cancer. 2001;91(7):1238-46.

11. Nissen MJ, Swenson KK, Kind EA. Quality of life after postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(3):547-53.

12. Rowland JH, Desmond KA, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR, Wyatt GE. Ganz PA. Role of breast reconstructive surgery in physical and emotional outcomes among breast cancer survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(17):1422-9.

13. Tkachenko GA, Arslanov KhS, Iakovlev VA, Blokhin SN, Shestopalova IM, Portnoi SM, et al. Long-term impact of breast reconstruction on quality of life among breast cancer patients. Vopr Onkol. 2008;54(6):724-8.

14. Al-Ghazal SK, Fallowfield L, Blamey RW. Comparison of psychological aspects and patient satisfaction following breast conserving surgery, simple mastectomy and breast reconstruction. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36(15):1938-43.

15. Dian D, Schwenn K, Mylonas L, Janni W, Friese K, Jaenicke F. Quality of life among breast cancer patients undergoing autologous breast reconstruction versus breast conserving therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133(4):247-52.

16. Mock V. Body image in women treated for breast cancer. Nursing Res. 1993;42(3):153-7.

17. Dean C, Chetty U, Forrest AP. Effects of immediate breast reconstruction on phychosocial morbidity after mastectomy. Lancet. 1983;1(8322):459-62.

18. Roth RS, Lowery JC, Davis J, Wilkins EG. Persistent pain following postmastectomy breast reconstruction: long-term effects of type and timing of surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58(4):371-6.

1. Foreign Medical Student of the Plastic Surgery and Reconstructive Microsurgery Residency Program of Walter Cantídio University Hospital, Federal University of Ceará (UFC), Fortaleza, CE, Brazil

2. Plastic Surgeon, full member of the Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica/Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery (SBCP), head of the Plastic Surgery and Reconstructive Microsurgery Service of Walter Cantídio University Hospital of UFC, supervisor of Plastic Surgery and Reconstructive Microsurgery Residency Program, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil

3. Medical student of UFC, member of the Plastic Surgery League of UFC, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil

Correspondence to:

Carolina Garzon Paredes

Avenida da Abolição, 2.111 - ap. 1.802 - Meireles

Fortaleza, CE, Brazil - CEP 60165-080

E-mail: caritog76@hotmail.com

Submitted to SGP (Sistema de Gestão de Publicações/Manager Publications System) of RBCP (Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica/Brazilian Journal of Plastic Surgery).

Article received: October 29, 2012

Article accepted: January 13, 2013

This study was performed at the Plastic Surgery and Reconstructive Microsurgery Service of Walter Cantídio University Hospital, Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, CE, Brazil.

All scientific articles published at www.rbcp.org.br are licensed under a Creative Commons license

All scientific articles published at www.rbcp.org.br are licensed under a Creative Commons license