Review Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Education for transgender women: Are the sources of information for the lay public sufficient?

Educação para mulheres transexuais: As fontes de informação para o público leigo são suficientes?

ABSTRACT

A transsexual woman is one assigned male at birth, but whose gender identity is female. This incompatibility can have negative impacts on socialization and trigger feelings of restlessness, anguish, and frustration. Given this, it is essential, not only for socialization purposes but also for self-acceptance, to adapt physical characteristics to the gender one wishes to express. The population of trans women must have access to pertinent information regarding methods and techniques that can not only minimize complaints and bring desires closer but can also guarantee safety and physical well-being. However, there is a gap in the literature regarding informative materials aimed at the lay trans population about facial feminization surgery. To externalize the exposed panorama, a systematic review of the literature was carried out in the MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, IBECS, LILACS, and SciELO databases. Although facial feminization surgery is a recurring topic, there was a lack of articles that addressed patient education on the topic. Facial feminization surgery is a broad term that covers several surgeries and procedures and the creation of informative material for the lay public is necessary. The development of educational technologies can help provide information regarding the benefits and risks of available modalities, as well as clarify doubts and help patients make decisions about the best treatment. In this sense, the contribution of written educational technologies in the context of promoting behavioral changes, prevention, and health becomes relevant.

Keywords: Education; Gender dysphoria; Transgender persons; Plastic surgery procedures; Review.

RESUMO

Mulher transexual é aquela designada como homem ao nascer, mas cuja identidade de gênero é feminina. Essa incompatibilidade pode provocar impactos negativos na socialização e desencadear sentimentos de inquietude, angústia e de frustação. Diante disso, é fundamental, não só para fins de socialização, como também de autoaceitação, adequar as características físicas com o gênero que se deseja expressar. É imprescindível que a população de mulheres trans tenha acesso a informações pertinentes quanto aos métodos e técnicas que não só possam minimizar queixas e aproximar desejos, como também possam garantir a segurança e o bem-estar físico. Todavia, percebe-se uma lacuna na literatura no que diz respeito a materiais informativos destinados à população trans leiga sobre a cirurgia de feminização facial. Com o propósito de externalizar o panorama exposto, foi realizada uma revisão sistematizada da literatura nas bases de dados MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, IBECS, LILACS e SciELO. Embora a cirurgia de feminização facial seja um tema recorrente, constatou-se a ausência de artigos que abordassem a educação do tema à paciente. Cirurgia de feminização facial é um termo amplo que abrange várias cirurgias e procedimentos e a construção de um material informativo para o público leigo se faz necessária. O desenvolvimento de tecnologias educativas pode ajudar a proporcionar informações quanto aos benefícios e riscos das modalidades disponíveis, bem como elucidar dúvidas e ajudar o paciente na tomada de decisão pelo melhor tratamento. Nesse sentido, torna-se relevante a contribuição de tecnologias educativas escritas no contexto de promover mudanças comportamentais, prevenção e saúde.

Palavras-chave: Educação; Disforia de gênero; Pessoas transgênero; Procedimentos de cirurgia plástica; Revisão.

INTRODUCTION

Transgender people are individuals whose gender identity or gender expression, how a person perceives itself and behaves, differs from the sex it was assigned at birth1. Gender dysphoria is the permanent feeling of anguish or discomfort resulting from the incompatibility between one’s identity and the sex assigned at birth2. Dysphoria can cause various psychopathologies, such as anxiety and depression, among others3. As it is an important tool for social interaction, the incompatibility between the masculine features of the face and the feminine gender expressed by the individual accentuates suffering, harming the social acceptance of transsexual women4.

To minimize the psychological discomfort resulting from gender dysphoria, in addition to psychotherapy and hormone therapy, facial gender confirmation surgery is a key part of the treatment3. Developed by Douglas Ousterhout, surgery plays an important role in the male-female transition, since, by modifying male characteristics, patients have demonstrated significant improvements in quality of life and emotional health5, 6.

Printed educational materials contribute to the communication process, in addition to increasing adherence to treatment and promoting decision-making power7. In the medical literature, there is a consensus on the benefit of written reinforcement of verbal instructions, as written guidance, written in an accessible manner, increases patient understanding and confidence in the health service, in addition to promoting better recovery after a surgical procedure8, 9. The population of transgender women must have access to quality information.

OBJECTIVE

Search the current panorama of information on facial feminization surgeries aimed at transgender women.

METHOD

A literature review was carried out using the MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, IBECS, LILACS, and SciELO databases. The included articles were published between 10/15/2018 and 10/15/2023 and the search strategies are described in Charts 1 and 2.

| (“Transgender persons” OR “Transgender person” OR “Transexual woman” OR Transfeminine) AND (Rhinoplasty OR “Rhytidectomy” OR “Botulinum toxin” OR “Dermal Fillers” OR “Male-to-female” OR Chondrolaryngoplasty OR “Tracheal Shave” OR “Facial feminization” OR Laryngochondroplasty OR (“Facial feminization” surgery) OR (“Facial Gender” surgery) OR “Cheek augmentation” OR FFS OR “Fat grafting” OR “Facial implant” OR Genioplasty OR “Mandibular angle reduction” OR “Chin feminization” OR (“Facial gender” “confirmation surgery”) OR “Adam’s Apple” OR “Thyroid notch” OR “Lip lift” OR “Nonsurgical cosmetic procedures” OR “Minimally invasive cosmetic procedures” OR “Noninvasive cosmetic procedures” OR “Orbital rim remodeling” OR (“Facial features” “remodeling surgery”) OR “Craniofacial surgery” OR “Periorbital surgery” OR “Forehead reconstruction” OR “Hairline” OR “Hairline lowering surgery” OR “Setback” OR “Perceived stigma” OR “Orbital shave” OR “Jaw shave” OR “Facial contouring”) AND (information* OR educat* OR complication*)) NOT (Masculinization OR Chest OR Genital) |

| (“Transgender persons” OR “Transgender person” OR “Transexual woman” OR Transfeminine) AND (Rhinoplasty OR “Rhytidectomy” OR “Botulinum toxin” OR “Dermal Fillers” OR “Male-to-female” OR Chondrolaryngoplasty OR “Tracheal Shave” OR “Facial feminization” OR Laryngochondroplasty OR (“Facial feminization” surgery) OR (“Facial Gender” surgery) OR “Cheek augmentation” OR FFS OR “Fat grafting” OR “Facial implant” OR Genioplasty OR “Mandibular angle reduction” OR “Chin feminization” OR (“Facial gender” “confirmation surgery”) OR “Adam’s Apple” OR “Thyroid notch” OR “Lip lift” OR “Nonsurgical cosmetic procedures” OR “Minimally invasive cosmetic procedures” OR “Noninvasive cosmetic procedures” OR “Orbital rim remodeling” OR (“Facial features” “remodeling surgery”) OR “Craniofacial surgery” OR “Periorbital surgery” OR “Forehead reconstruction” OR “Hairline” OR “Hairline lowering surgery” OR “Setback” OR “Perceived stigma” OR “Orbital shave” OR “Jaw shave” OR “Facial contouring”) AND (information* OR educat* OR complication*)) AND NOT (Masculinization OR Chest OR Genital) |

As an inclusion criterion, publications in Portuguese, English, and Spanish were included, cataloged in full in the databases, and that addressed the topic of information for transsexual patients about facial feminization surgeries. The exclusion criteria eliminated articles whose main theme was voice or body surgeries, the health of the trans population in general, mental and emotional health, and medical education, in addition to duplicate articles.

At the same time, a search was carried out for informative materials, printed or digital, aimed at the public on the search sites: Google®, Yahoo® and Bing®, in July 2022 and repeated in October 2023. Specifically on the Google® website, searches were made for the keywords: “feminização facial”, “manual”, “livro”, “e-book” and “guia”, using the Google Chrome browser, in the first ten pages of results.

RESULTS

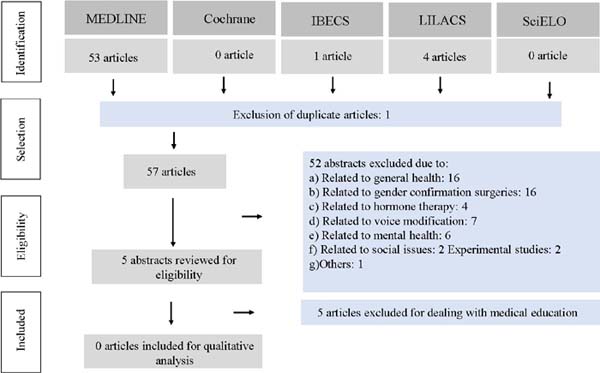

The search resulted in 57 articles, after eliminating duplications. Screening by title and abstract resulted in the exclusion of 52 articles based on relevance. Most of these articles addressed surgical techniques and the general health of the transsexual population. The article selection flowchart is shown in Figure 1.

The abstract of 5 articles was reviewed for eligibility. All of these were excluded, as they relate to medical education only and did not address patient education (Chart 3).

| AUTHOR | YEAR | TITLE | OBJECTIVE | CONCLUSION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buhalog, et al. | 2019 | Trainee Exposure and Education for Minimally Invasive Gender-Affirming Procedures | This article assesses the current amount of trainee exposure in clinic and didactic sessions in core procedural specialties nationwide via survey study of program directors. | Low exposure of residents and fellows to MIGAPs was observed overall and a lack of procedure-specific education. In an effort to provide excellent patient care, promote cultural humility, and improve patients’ quality of life, further education regarding these procedures is necessary. |

| Chipkin & Kim | 2017 | Ten Most Important Things to Know About Caring for Transgender Patients | Ten key principles are provided to help primary care practitioners create more welcoming environments and provide quality care to transgender patients. | Primary care providers also should be aware of resources in their community and online, which can help patients optimize their transition. |

| Vinekar et al. | 2019 | Educating Obstetrics and Gynecology Residents on Transgender Patients: A Survey Program Directors | To describe education on transgender health provided by obstetrics and gynecology residency programs and to identify the facilitators and barriers to providing this training. | Our survey of obstetrics and gynecology residency programs highlights the interest in transgender health education for a systemically underserved population of patients. |

| Chisolm-Straker et al | 2018 | Transgender and Gender-nonconforming Patients in the Emergency Department: What a Physicians Know, Think and Do | We explore self-reported knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors of emergency physicians in regard to the care of transgender and gender-nonconforming patients to identify opportunities to improve care of this population. | Although transgender and gender-nonconforming people represent a minority of ED patients nationwide, the majority of respondents reported personally providing care to members of this population. Most respondents lacked basic clinical knowledge about transgender and gender-nonconforming care. |

| Pfaff et al | 2020 | A Structured Facial Feminizations Fresh Tissue Surgical Somulation Laboratory Improves Trainee Confidence and Knowledge | A key element of gender-affirming surgery includes facial feminization, which necessitates a detailed understanding of the anatomical features that differ between female and male bony and soft tissues.3 In this communication, we describe our experience with a structured facial feminization cadaver laboratory and evaluate its educational value in plastic surgery training. | Simulation models are also valuable for less common procedures or where exposure of surgical trainees to such specialized cases may be limited but desired, as in gender-affirming surgery.5 Efforts to build on this curriculum and improve resident understanding within this relatively new and rapidly evolving field within the specialty are ongoing |

The search for educational materials found only five products on facial feminization procedures in transgender women for the public, however, presenting several limitations (Chart 4).

| AUTHOR | YEAR | TITLE | TYPE | LIMITATION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coleman et al. | 2012 | Standarts of Care fot the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7 | manual | Focus on definitions, hormonal treatment and body surgeries. Only cites facial surgeries |

| Simpson & Goldenberg | 2016 | Surgery: A guide dor MTFs | manual | It offers only an overview of facial surgeries. The content is very short and lacks scientific rigor in its preparation |

| Eric Plemons | 2017 | The look of a woman | printed book | Addresses the subject from an anthropological perspective. It does not mention feminization surgeries |

| José Carlos Martins Jr | 2020 | Transgêneros: Orientações médicas para uma transição segura | printed book | Available only in Portuguese. It presents the personal opinion of an individual, and there is a personal marketing bias |

| Deschamps & Ousterhout | 2021 | Facial Feminization: Facial Feminization Surgery: The Journey to Gender Affirmation - Second Edition | printed book | High-cost book. It presents the view of two experts on the subject but lacks scientific rigor |

DISCUSSION

In the past, numerous anthropological studies have addressed the anatomical differences in the bone structure and soft tissues between the male and female face. In recent years, facial feminization surgery has been a popular topic in medical literature, but with an emphasis on medical education and not addressing patient education.

Of the five materials found on search platforms, two do not provide information about facial feminization surgery, being a printed book that addresses anthropological aspects and a free manual available in several languages, although until the last version it only mentions facial surgeries. The remaining three have content on facial feminization surgery written for the public, however, in addition to being a very restricted number of products, they all still have limitations: a high-cost printed book available only in English, a high-cost printed book available only in Portuguese and a free and very brief digital manual available only in English. It should be noted that none of the material was prepared with scientific rigor, that is, it was written based on articles selected through a systematic review of the topic.

There is a growing interest in research that addresses the need for patient information, but there is a lack of work on the importance of this topic regarding the transsexual population. Such studies are pertinent, as the trans population suffers from social exclusion and marginalization, and from prejudices that make it difficult to consult health topics with quality and credibility, which result in more unfavorable health outcomes when compared to the general population10, 11.

Facial feminization surgery is a broad term that encompasses various surgeries and procedures on the face, such as the forehead, nose, cheeks, and neck, intending to make the face more feminine. Trans women who suffer from gender dysphoria must know what types of treatment are available, as well as general information about each one, including risks so that they can seek treatment according to their needs and be sure that this information is accessible, serious, and assertive. A study of search parameters on Google Trend showed that the search for facial feminization procedures on the Internet tripled between 2008 and 2018, showing a growing interest in the topic among the public12.

A systematic review looking at the state of the art on consumer health education concluded that it is important to make efforts to improve the quality of digital health information, given the impact of these media today13.

One of the ways to educate patients is through digital material. Tablets containing informative health material were distributed in waiting rooms and caused a feeling of greater education on the part of patients on health topics of interest7. The topic of facial feminization is complex and verbal information alone may be insufficient. Creating support materials for consultations, such as tablets in the waiting room, and post-consultation emails with extra reading, among others, can help consolidate the information provided.

The development of educational technologies can promote behavioral changes, making the client confident in carrying out certain health-promoting behaviors. Among these educational technologies, the educational manual stands out, which helps in memorizing content and contributes to the direction of health education activities14, 15.

It is desirable that multiple communication strategies are developed to inform the public at all stages of treatment and the private sector can significantly contribute to the development of this type of material. This resource is of great relevance, considering that a considerable number of patients find it difficult to acquire basic health information.

In this sense, the contribution of written educational technologies in the context of health education and the role of this resource in promoting health, preventing complications, developing skills, and promoting patient autonomy and confidence becomes relevant.

Educational materials contribute favorably to the decision-making process, increase treatment adherence, and promote better recovery in surgical procedures, as they offer consistent information and reinforce verbal instruction. Due to the great interest in the topic and condition of social exclusion, investment should be made in the development of educational materials on facial feminization for the transsexual population and research into its impact.

CONCLUSION

Despite the relevance of the topic, there are no articles in the medical literature that address the importance of education about facial feminization surgeries aimed at the lay public.

REFERENCES

1. Bockting WO. Psychotherapy and real-life experience: from gender dichotomy to gender diversity. Sexologies. 2008;17(4):211-24.

2. American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5 R). 5th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. p. 451-60.

3. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, Decuypere G, Feldman J, Et Al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7. Int J Transgend. 2012;13(4)165-232.

4. Reisner SL, Poteat T, Keatley J, Cabral M, Mothopeng T, Dunham E, et al. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: a review. Lancet. 2016;388(10042):412-36. DOI: 10.1016/S0140- 6736(16)00684-X

5. Chou DW, Bruss D, Tejani N, Brandstetter K, Kleinberger A, Shih C. Quality of Life Outcomes After Facial Feminization Surgery. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2022;24(S2):S44-6. DOI: 10.1089/fpsam.2021.0373

6. Nuyen B, Kandathil C, McDonald D, Chou DW, Shih C, Most SP The Health Burden of Transfeminine Facial Gender Dysphoria: An Analysis of Public Perception. Facial Plast Surg Aesthet Med. 2021;23(5):350-6. DOI: 10.1089/fpsam.2020.0192

7. Stribling JC, Richardson JE. Placing wireless tablets in clinical settings for patient education. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104(2):159-64. DOI: 10.3163/1536- 5050.104.2.013

8. Lee SY, Wang TJ, Hwang GJ, Chang SC. Effects of the use of interactive E- books by intensive care unit patients’ family members: anxiety, learning performances and perceptions. Br J Educ Technol. 2019;50(2):888-901.

9. Martínez-Miranda IP Casuso-Holgado MJ, Jesús Jiménez-Rejano J. Effect of patient education on quality-of-life, pain and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil. 2021;35(12):1722-42. DOI: 10.1177/02692155211031081

10. White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:222-31. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010

11. Macapagal K, Bhatia R, Greene GJ. Differences in Healthcare Access, Use, and Experiences Within a Community Sample of Racially Diverse Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Emerging Adults. LGBT Health. 2016;3(6):434-42. DOI: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0124

12. Teixeira JC, Morrison SD, Brandstetter KA, Nuara MJ. Is There an Increasing Interest in Facial Feminization Surgery? A Search Trends Analysis. J Craniofac Surg. 2020;31(3):606-7. DOI: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000006220

13. Fernandez-Luque L, Staccini P. All that Glitters Is not Gold: Consumer Health Informatics and Education in the Era of Social Media and Health Apps. Findings from the Yearbook 2016 Section on Consumer Health Informatics. Yearb Med Inform. 2016;10(1):188-93. DOI: 10.15265/IY-2016-045

14. Teles LM, Oliveira AS, Campos FC, Lima TM, Costa CC, Gomes LF, et al. Construção e validação de manual educativo para acompanhantes durante o trabalho de parto e parto. Rev Esc Enferm USP 2014;48(6):977-84. DOI: 10.1590/S0080-623420140000700003

15. Schnitman G, Wang T, Kundu S, Turkdogan S, Gotlieb R, How J, et al. The role of digital patient education in maternal health: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(3):586-93. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.06.019

1. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, São Paulo, SIP Brazil

Corresponding author: Patricia de Azevedo Marques Av. Moema, 300, conjunto 71, São Paulo, SP Brazil. Zip Code: 04077-020. E-mail: consultorio@drapatriciamarques.com.br

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter