Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Prevalence of cleft lip and palate in Brazil and its notification in the information system

Prevalência de fissuras labiopalatais no Brasil e sua notificação no sistema de informação

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Cleft lip and palate is the most common congenital deformity, with an incidence of 1.53/1000 live births, and treatment is predominantly carried out in the Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde SUS). In 1999, the Live Birth Information System (Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos SINASC) implemented the gap to be filled in regarding congenital deformities. Studies have demonstrated the significant underreporting of the fissure in SINASC.

Method: The number of children born per year in Brazil between 2012 and 2018 was surveyed in the respective regions, projecting the number of cleft children born per year using the proportion 1.53/1000 live births. From these data, the number of cleft patients notified in the SUS system was observed and compared with the projection made by observing an estimate of notification by region. The evolution of government spending by region on cleft lip and palate surgery in the period from 2012 to 2018 was also verified.

Results: There was a notification of 54.1% to 36.7% of children born with cleft, with the Southeast Region having the best rate and the Northeast with the lowest notification rate. Federal spending on cleft lip and palate surgery decreased between 2012 and 2018, compared to the number of births with clefts, which remained stable during this period.

Conclusion: Although SINASC is an important tool, the significant underreporting of this condition impacts public policies, as it uses data inconsistent with reality. Another concern is the decrease in federal spending on cleft surgery, which shows that more children are failing to receive adequate treatment.

Keywords: Prevalence; Cleft lip; Cleft palate; Health information systems; Unified Health System.

RESUMO

Introdução: A fissura labiopalatina é a deformidade congênita mais comum, com uma incidência de 1,53/1000 nascidos vivos e o tratamento predominantemente realizado no Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). Em 1999, o Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos (SINASC) implantou a lacuna para preenchimento referente a deformidade congênita. Trabalhos vêm demostrando a subnotificação importante da fissura no SINASC.

Método: Foi levantado o número de crianças nascidas por ano no Brasil entre 2012 e 2018 nas respectivas regiões, projetando o número de fissurados nascidos por ano usando a proporção 1,53/1000 nascidos vivos. A partir destes dados, observado o número de fissurados notificados no sistema SUS e comparado com a projeção feita observando uma estimativa de notificação por região. Verificada também a evolução dos gastos governamentais por região com cirurgia de fissura labiopalatina no período de 2012 a 2018.

Resultados: Houve uma notificação de 54,1% a 36,7% das crianças nascidas com fissura, sendo a Região Sudeste com melhor índice e o Nordeste com o índice mais baixo de notificação. Os gastos federais em cirurgia de fissura labiopalatina diminuíram entre 2012 e 2018, frente ao número de nascimentos com fissuras, que se manteve estável neste período.

Conclusão: Apesar do SINASC ser uma ferramenta importante, as subnotificações expressivas desta afecção impactam nas políticas públicas, pois utilizam dados inconsistentes com a realidade. Outra preocupação é a diminuição dos gastos federais com cirurgias de fissurados, o que demostra que mais crianças estão deixando de receber tratamento adequado.

Palavras-chave: Prevalência; Fenda labial; Fissura palatina; Sistemas de informação em saúde; Sistema Único de Saúde.

INTRODUCTION

Cleft lip and palate are the most common congenital malformations and may be associated with more than 250 syndromes1. Most cases are isolated and are called non-syndromic. Its presentation is varied, ranging from isolated cleft lip or palate, such as unilateral or complete bilateral cleft lip and palate, to rare clefts associated with other syndromes. In Brazil, the Spina2 classification is adopted, among the various classifications existing in the literature.

This condition causes several changes, affecting facial growth, speech, and facial aesthetics, which leads to psychosocial repercussions. Its monitoring begins at birth and continues until complete facial development in adulthood. The treatment is based on a minimum basic structure consisting of a plastic surgeon, orthodontist, and speech therapist. To obtain the best results for each case, all members must have treatment experience and patient engagement in treatment protocols.

The predominant care for these patients occurs in the Unified Health System (SUS) of the Ministry of Health, a free public system3.

Brazilian notification began in 1990 when the Ministry of Health implemented the Live Birth Information System (SINASC). This system uses as a data source the Declaration of Live Birth (Declaração de Nascido Vivo DNV) - an official document issued by maternity hospitals - without which parents cannot carry out civil registration4. This was an important milestone for obtaining data. However, it did not include congenital malformations.

Only in 1999 did the Ministry of Health update the Declaration of Live Birth (DNV), with the inclusion of a new mandatory registration field - field 34 - intended for recording the presence or absence of congenital malformations. Field 34 of the DNV has the following question as its title: “Have any congenital malformations or chromosomal abnormalities been detected?” Next, three items are presented. The first item is a closed question, with the following options: 1-Yes; 2-No; 99-Ignored. The second item, “Which?”, is an open question to describe the type of anomaly found, and the last, “Code”, is to introduce the ICD-10 International Code of Diseases code corresponding to the malformation described5, but only could be identified by unique code. After 2011, DNV allowed the use of several ICD-10 codes.

These innovations at SINASC allowed health information teams, based in municipal health departments, to start recording congenital anomalies systematically, creating the basic conditions for the implementation of a municipal system for monitoring congenital defects.

In Brazil, the ratio is estimated at one case for every 650 births (1.53/1000 live births), this being the most accepted ratio. There are other studies to estimate this relationship and these have low reliability because they use small samples and are generally restricted to hospital statistics in a locality6.

Observing the incidence in other countries, we have a wide variation, ranging from 1.0/1,000 NV to 1.81/1,000 NV. The highest incidence was found in the Czech Republic (1.81/1,000), followed by France (1.75/1,000), Finland (1.74/1,000), Denmark (1.69/1,000), Belgium, and the Netherlands (1.47/1,000), Italy (1.33/1,000) and California, in the United States (1.12/1,000)7-9. According to data from the Ministry of Health/SINASC, the prevalence of this malformation in Brazil was on the order of 0.5/1000 LB in the period from 2000 to 201110.

Few studies evaluate this level of mandatory notification in maternity hospitals and those available regarding cleft lip and palate report notification of 47% of cases of cleft lip and palate, the lowest being in isolated cleft palates, reaching only 30%11-13. In another study, with the level of notification of patients identified as having a cleft, only 37% had been notified14.

The work related to CADEFI/IMIP of Pernambuco15 is of relevant importance, as it is the only fissure service in the state. The number of children born in 2009 who presented themselves to the service was collected and compared to SINASC data. There was a high underreporting of cleft lip and/or palate among live births. The incidence of patients who attended the service was 1.55/1000 NV, close to the consensus of 1.53/1000 NV and far from that presented in SINASC with 0.55/1000 NV.

The lack of concrete data provided by SINASC due to underreporting leads to incorrect data in scientific studies that use this data source16,17 and makes it difficult for government agencies to plan and apply public policies for the care of children with this condition.

OBJECTIVE

The objective of this work is: 1) to survey the number of children born per year between 2012 and 2018 in the respective Brazilian regions, to project the number of cleft children born per year using the proportion 1.53/1000 live births. From these data, collect the number of cleft patients reported in the SINASC system and compare it with the projection made by observing an estimate of underreporting by region. 2) Verify the evolution of government spending by year and regions in Brazil with cleft lip and palate surgery in the period from 2012 to 2018.

METHOD

This is an observational, descriptive, and retrospective epidemiological study with a documentary approach, carried out using secondary data in the public domain. Held in Brazil and divided by region: North, Northeast, Southeast, South, and Central-West. The study period ranged from January 2012 to December 2018, at the Faculdade Bahiana de Medicina, Cleft Lip and Palate Service.

The prevalence and underreporting study was carried out using information on live births with cleft lip and palate in the Live Birth Information System (SINASC) and accessible through the SUS IT Department platform (DATASUS), during the study period.

The evaluation of expenditure per year on cleft lip and palate surgery from 2012 to 2018 by region used the codes provided by the SUS. In Brazil, spending on treating these patients is predominantly public. All surgical procedure codes relating to patients with cleft lip and/or palate, registered in the Hospital Information System (SIH/SUS), also through DATASUS, were considered. The related procedures are 0404030017 - columella lengthening in a patient with cranial and maxillofacial anomalies, 0404030033 - maxillary osteotomies in patients with cranial and maxillofacial anomalies, 0404030050 - mandibular osteotomy in a patient with cranial and maxillofacial anomalies, 0404030076 - unilateral labiaplasty in two stages , 0404030084 - alveoloplasty with bone graft in a patient with craniofacial anomaly, 0404030092 - partial / total palatoplasty, 0404030106 - primary palatoplasty in a patient with cranial and maxillofacial anomaly, 0404030122 - secondary labiaplasty in a patient with cranial and maxillofacial anomaly, 0404030130 - rhinoseptoplasty in a patient with skull and maxillofacial anomaly, 0404030165 - rhinoplasty in a patient with skull and maxillofacial anomaly, 0404030173 - septoplasty in a patient with skull and maxillofacial anomaly, 0404030203 - surgical treatment of cleft lip (includes cleft lip and palate), 0404030211 - non-aesthetic repair surgical treatment of the nose in patient with craniofacial deformity, 0404030220 - extraoral maxillofacial osteointegrated implant, 0404030254 - surgical treatment of oronasal fistulas in a patient with cranial and maxillofacial anomaly, 0404030262 - secondary palatoplasty in a patient with craniofacial anomaly, 0404030270 - surgical treatment of velus insufficiency pharyngeal in patient with skull and maxillofacial anomaly.

The data used were stored in Microsoft Office Excel 2010, and descriptive analyses were carried out, using tables with absolute number (n) and relative frequency (%) for categorical data. As a measure of central tendency, the mean was used to compare values. As a way of summarizing the results, they were presented in tables and figures. The incidence coefficient was calculated using the total number of cases in the year as the numerator and the number of live births in the same year as the denominator and the result was multiplied by 1000. The SINASC values were compared with the ratio of 1.53/1000 NV, and the percentage of notification was calculated and presented in a figure by region.

There was no submission to the Permanent Ethics Committee for Research Involving Human Beings under letter no. 08/2018, based on Resolutions 466/12 - CNS/MS and 510/2016 - CNS/MS, as this is a study with database data in the public and unrestricted domain without identifying individuals.

RESULTS

Between 2012 and 2018, the North, Northeast, Southeast, South, and Central-West regions presented the following data on the number of children born alive by region per year in Brazil (Table 1).

| YEAR/ REGION | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NORTH | 308,375 | 313,272 | 321.682 | 320,924 | 307,526 | 312,682 | 319,228 |

| NORTH EAST | 832,631 | 821,458 | 833,090 | 846,374 | 796,119 | 817,311 | 836,850 |

| SOUTHEAST | 1,152,846 | 1,147,627 | 1,182,949 | 1,196,232 | 1,127,499 | 1,151,832 | 1,147,006 |

| SOUTH | 381,658 | 386,983 | 396,462 | 406,529 | 391,790 | 397,604 | 395,857 |

| MIDWEST | 230,279 | 234,687 | 245,076 | 247,609 | 234,866 | 244,106 | 245,991 |

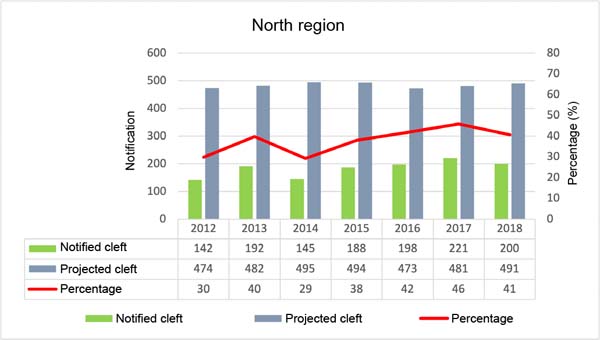

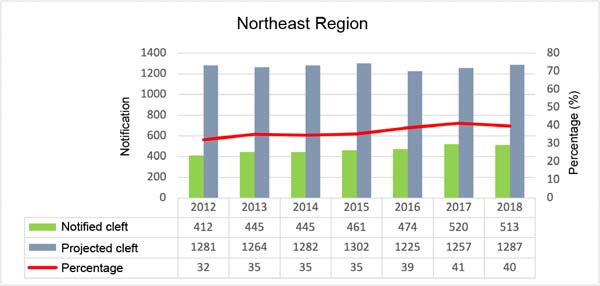

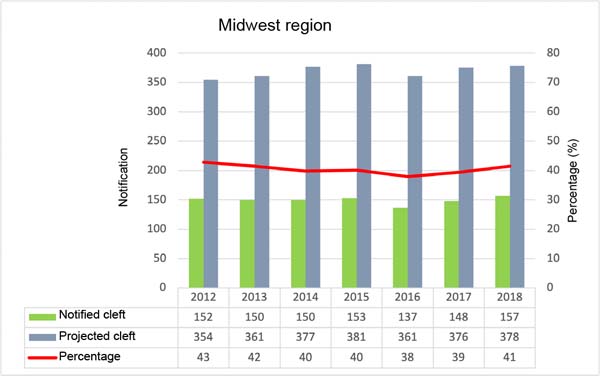

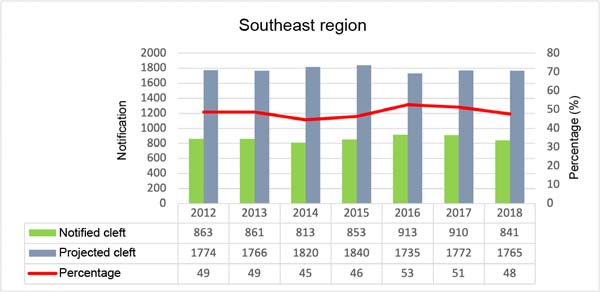

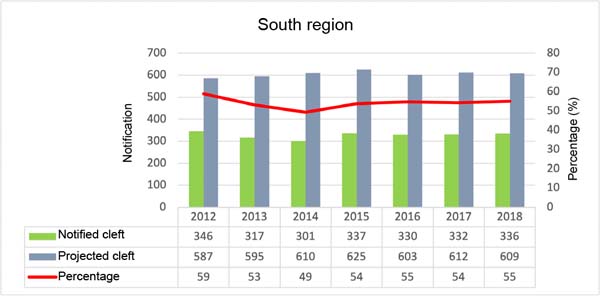

Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 are, respectively, referring to each region of Brazil. The first column represents the number of children born with cleft lip and palate reported in the SINASC system; in the second column the projection of children who should be notified following the proportion 1.53/1000 live births per year. In this figure, there is a line that indicates the percentage of patients notified. When looking at the saverage notification percentage by region, the one with the best rate is the South Region, with an average of 54.1%; next comes the Southeast, with 48.7; Central-West, with 40.4%; North, 38%; and with 36.7% the Northeast Region.

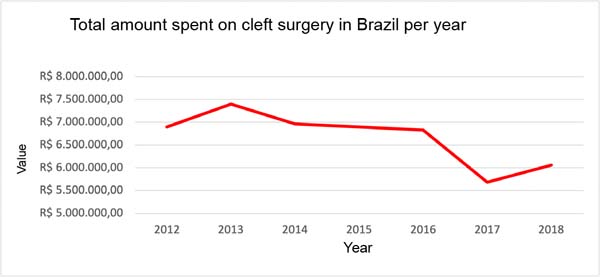

Figure 6 refers to the amounts spent on surgical procedures performed to treat cleft lip and palate in Brazil from 2012 to 2018 with the codes collected in DATASUS. There was a gradual drop in spending from 2013 onwards, being more pronounced in 2016-2017, rising again in 2018, but lower compared to 2012 and 2013.

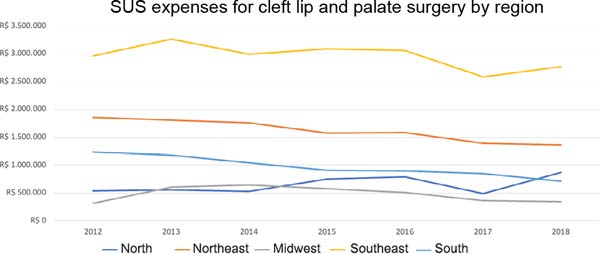

In Figure 7 we have spending on surgical procedures for cleft patients by region from 2012 to 2018. We observe the North Region to be different from the other regions, with an increase in spending on cleft surgeries. All other regions showed a decrease in spending on cleft surgery.

DISCUSSION

The implementation of SINASC in Brazil was an important milestone and, later, its improvement in 1999, creating field 34, represented another important advance in mapping children with congenital deformities in Brazil. Although the data is freely accessible to the public, the data regarding cleft lip and palate are not reliable.

The incidence of one cleft for every 650 births or 1.53/1000 is the most accepted and published incidence among Brazilian authors. If we compare with the global incidence, we can observe that the smaller the population of a country and the better the educational level combined with an integrated computerized health system, increases the incidence and leads to more consistent data. Several factors may interfere with this incidence and are not very clear, so variation is expected.

The highest incidence was found in the Czech Republic (1.81/1,000), followed by France (1.75/1,000), Finland (1.74/1,000), Denmark (1.69/1,000), Belgium and the Netherlands (1.47/1,000), Italy (1.33/1,000). If we calculate by SINASC, the proportion of live births in Brazil will vary from 0.46-0.57/1000 births per region, a number well below that of European countries. Studies demonstrate significant underreporting in the government system.

The work carried out in Pernambuco, with only one service that serves the entire state, presents a proportion of 1.55/1000 births, very close to 1.53/1000, a value accepted by the scientific community. Therefore, underreporting can be considered high in Brazil. The SINASC system presents in its databases the lowest percentage of notifications at 28% and the highest percentage at 59% of children born with clefts in Brazil. Noting that the lowest value was in the North Region, a region with the largest area and difficulty in accessing the public health network. The South Region had the best notification - the opposite of the conditions in the North Region plus the best human development index (HDI)18.

Inaccurate data leads to distortions both in scientific publications, which use them as the only source of data, and in public policies adopted at the municipal, state, and federal levels. The MS-SINASC data do not show the extent of the problem of children with cleft lip and palate in Brazil.

The policies of high-complexity centers must be reviewed. Centers of medium complexity with more than 10 years of operation with an interdisciplinary team (plastic surgeon, orthodontist, and speech therapist) can be registered by the Ministry of Health in high complexity.

Effective training and recycling policies must be programmed by the Ministry of Health to improve professionals directly linked to filling out the form, thus allowing a more faithful sampling for public policies.

Government spending on surgeries to treat cleft lip and palate had its highest value by region in 2013. In the following years, we observed a decrease in spending on these procedures. The significant drop in spending from 2016 to 2017 reflects the inflationary scenario and political instability in which the president is impeached and takes over a new government. The increase in spending in the North Region coincides with the organization of new cleft surgery centers and joint efforts carried out during this period.

Births continue and the amounts spent decrease, consequently, more children no longer receive adequate treatment. The values for these procedures paid by the SUS need to be adjusted, as many units such as philanthropic organizations and municipalities are no longer carrying out the procedure, claiming that the amounts paid do not cover the costs. This point directly impacts the increase in children who do not have access to adequate treatment.

CONCLUSION

When evaluating data from the Ministry of Health and published work on the prevalence of clefts in the Brazilian population, we can state that there is a significant underreporting of newborns with this congenital deformity, resulting in a discrepancy in public policies and studies that use this source of data. Efforts and measures to bring these data closer to reality must be implemented. SUS spending on cleft surgeries should increase, as well as updating policies for new centers and reclassifying centers for high complexity. These measures will enable better care for children with this condition throughout the country.

REFERENCES

1. Jones MC. Facial clefting. Etiology and developmental pathogenesis. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20(4):599-606.

2. Spina V, Psillakis JM, Lapa FS, Ferreira MC. Classificação das fissuras lábio-palatinas: sugestão de modificação. Rev Hosp Fac Med Sao Paulo. 1972;27(1):5-6.

3. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Fissura Labiopalatal. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2019. http://www.saude.gov.br/atencaoespecializada-e-hospitalar/especialidades/cirurgia-plastica-reparadora/fissuralabiopalatal

4. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Fundação Nacional de Saúde. Manual de procedimentos do sistema de informações sobre nascidos vivos. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2001.

5. Aerts D, Cunha J, Livi K, Leite JC, Flores R. Defeitos congênitos em Porto Alegre: uma estratégia para o resgate do sub-registro no SINASC. In: Anais da 3 Expoepi: Mostra Nacional de experiências Bem-Sucedidas em Epidemiologia, Prevenção e Controle de Doenças 2003. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde; 2004. p. 102-5.

6. Capelozza-Filho L, Silva-Filho OG. Abordagem Interdisciplinar no tratamento das Fissuras labiopalatinas. In: Mélega JM, Baroudi R, eds. Cirurgia Plástica fundamentos e arte. Cirurgia reparadora Cabeça e pescoço. Rio de Janeiro: Medsi; 2003 p. 60-2.

7. Czeizel A. Studies of cleft lip and cleft palate in east European populations. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1980;46:249-96.

8. Tolarová M. Orofacial clefts in Czechoslovakia. Incidence, genetics and prevention of cleft lip and palate over a 19-year period. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1987;21(1):19-25.

9. Derijcke A, Eerens A, Carels C. The incidence of oral clefts: a review. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;34(6):488-94.

10. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Departamento de Informática do SUS. Informações de Saúde. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde [acesso 2013 Dez 17]. Disponível em: http://www.datasus.gov.br

11. Lima CRA, Schramm JMA, Coeli CM, Silva MEM. Revisão das dimensões de qualidade dos dados e métodos aplicados na avaliação dos sistemas de informação em saúde. Cad Saúde Pública. 2009;25(10):2095-109.

12. Nunes LMN. Prevalência de fissuras labiopalatais e sua notificação no sistema de informação [Dissertação de Mestrado]. Piracicaba: Universidade Estadual de Campinas; 2005.

13. Mello Jorge MHP, Gotlieb SLD, Soboll MLMS, Almeida MF, Latorre MRDO. Avaliação do sistema de informação sobre nascidos vivos e o uso de seus dados em epidemiologia e estatísticas de saúde. Rev Saúde Pública. 1993;27(supl):1-46.

14. Souza J, Raskin S. Estudo clínico e epidemiológico de fissuras orofaciais. J Pediatr (Rio J.). 2013;89(2):137-44.

15. Nunes LMN, Pereira AC, Queluz DP. Fissuras orais e sua notificação no sistema de informação: análise da Declaração de Nascido Vivo (DNV) em Campos dos Goytacazes - RJ, 1999-2004. Ciênc Saúde Coletiva. 2010;15(2):345-52.

16. Santana TM, Silva MDP, Brandão SR, Gomes AOC, Pereira RMR, Rodrigues M. Nascidos vivos com fissura de lábio e/ou palato: as contribuições da fonoaudiologia para o Sinasc. Rev CEFAC. 2015;17(2):485-91.

17. Shibukawa BMC, Rissi GP, Higarashi LH, Oliveira RR. Factors associated with the presence of cleft lip/or palate in Brazilian newborns. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant. 2019;19(4):947-56.

18. Sousa GFT, Roncalli AG. Fatores associados ao atraso no tratamento cirúrgico primário de fissuras labiopalatinas no Brasil: uma análise multinível. Ciênc Saúde Colet. 2021;26(Suppl. 2):3505-15.

1. Escola Bahiana de Medicina, Salvador, BA, Brazil

Corresponding author: Géza Lászlo Urményi Rua Sol Nascente, 43, Ed. Vitarux, Sala 701, Rio Vermelho, Salvador, BA, Brazil, Zip Code: 41940-457, E-mail: geza701@gmail.com

Article received: June 5, 2023.

Article accepted: December 5, 2023.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter