Review Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Aesthetic Surgical Procedures in Patients Diagnosed with Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Procedimentos cirúrgicos estéticos em pacientes diagnosticados com transtorno dismórfico corporal

ABSTRACT

Introduction Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), a common psychiatric condition in patients who are candidates for plastic surgery, is characterized by dysmorphia/defects imagined by the patient about their body, but which are unrealistic or poorly perceived by other people, in addition to repetitive behaviors or mental acts in response to these concerns.

Objective To describe the incidence of patients undergoing plastic surgery who present BDD, and to analyze the postoperative acceptance and the factors that alter the satisfaction with the outcome, which plastic procedures are most sought after by these patients, and the respective conduct of surgeons in these cases.

Materials and Methods We conducted a literature review on the PubMed and SciELO databases using the descriptors body dysmorphic disorder and plastic surgery.

Results Body dysmorphic disorder is the most important condition for aesthetic procedures today. It reduces quality of life, and the most severe cases present a risk of suicidal ideation and attempts. Discussion Since Brazil is the leading country in aesthetic procedures, professionals must know how to recognize and treat these patients early, using specific therapies and a multidisciplinary approach, assessing the severity of each case and the need for surgical cancellations.

Conclusion Caution becomes an essential medical quality, as this is not an aesthetic problem, but a mental disorder.

Keywords: body image; aesthetics; mental disorders; patient satisfaction; plastic surgery

RESUMO

Introdução O transtorno dismórfico corporal (TDC), patologia psiquiátrica frequente em pacientes candidatos à cirurgia plástica, é caracterizado por dismorfias/defeitos que o paciente imagina sobre o seu corpo, mas que são irreais ou pouco percebidos pelas outras pessoas, e também por comportamentos repetitivos ou atos mentais em resposta a essas preocupações.

Objetivo Descrever a incidência de pacientes submetidos a cirurgia plástica e portadores do TDC, e analisar a aceitação pós-operatória e os fatores que alteram a satisfação dos resultados, quais os procedimentos plásticos mais procurados por estes pacientes, e a respectiva conduta dos cirurgiões frente a esses casos.

Materiais e Métodos Foi realizada uma revisão da literatura nas bases de dados PubMed e SciELO com os seguintes descritores em inglês: body dysmorphic disorder e plastic surgery.

Resultados Os resultados apontam que oTDC é a patologia de maior importância para os procedimentos estéticos da atualidade, além de contribuir para uma pior qualidade de vida; nos casos mais graves, também há o risco da ideação e da tentativa de suicídio.

Discussão Sendo o Brasil o país campeão na realização de procedimentos estéticos, seus profissionais devem estar preparados para reconhecer e tratar de forma precoce esses pacientes, utilizar terapêutica específica e abordagem multidisciplinar, e avaliar a gravidade de cada caso e a necessidade de cancelamentos cirúrgicos.

Conclusão A cautela torna-se em uma qualidade médica essencial, uma vez que não se trata de um problema estético, mas de um transtorno mental.

Palavras-chave: cirurgia plástica; estética; imagem corporal; satisfação do paciente; transtornos mentais

Introduction

Body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) is a mental illness characterized by the perception of body dysmorphia; it is part of the obsessive-compulsive disorders, and it consists in obsessive thoughts about an imaginary defect in appearance that does not match reality.1,2,3,4,5 Patients suffering from BDD often spend hours a day thinking about their appearance, potentially with compulsive actions, such as repeatedly looking at themselves in the mirror, or constantly comparing their appearance to that of other people.6,7,8,9,10 The disorder also results in significant distress, impaired functioning, social withdrawal, and repeated attempts to hide or correct the imagined defect.11,12,13

Patients with BDD have ideas or delusions of reference, high levels of social anxiety, social avoidance, depressed mood, perfectionism, and neuroticism, in addition to low self-esteem and low extroversion.11,14,15 Although most BDD patients seek aesthetic procedures to correct their perceived defects, they seem to respond poorly to such treatments, and, sometimes, their disorder gets worse. The variables influencing the disorder include gender, socioeconomic level, and age.16,17,18,19,20,21

Objective

The present study aimed to describe the incidence of patients undergoing plastic surgery who have BDD and to analyze postoperative acceptance and the factors altering outcome satisfaction, thus elucidating which plastic procedures are most sought after by these patients and the respective conduct of surgeons in these cases.

Materials and Methods

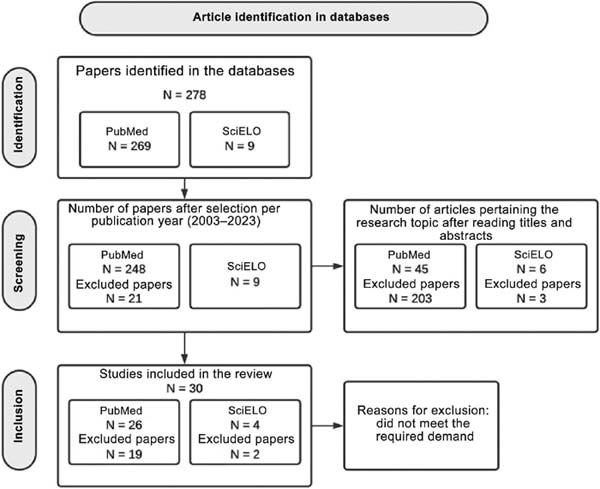

The present is an original article. We surveyed the PubMed and SciELO databases for articles using the descriptors body dysmorphic disorder and plastic surgery. Furthermore, the search was restricted to articles published from March 2003 to June 2023. Articles deemed irrelevant and not about the subject in question were excluded, as well as those repeated in the database. The following flowchart (►Fig. 1) presents the methodology for article selection.

Results

At first, we identified 278 articles; after the application of the criterion of the year of publication, we excluded 21 articles. After reading the titles and abstracts, we selected 51 articles. After further screening, only 30 articles remained in the selection.

Discussion

Psychiatric disorders and plastic surgery

In 2009, Conrado conducted a study analyzing the prevalence of BBD in the general population, and found a rate of up to 2.4%.6 For patients who seek and undergo plastic surgery, this rate can range from 6 to 54%.3,7 Sun and Rieder,4 in a meta-analysis, stated that 15.04% of all plastic surgery patients meet the diagnostic criteria for BDD. The disease is more prevalent among patients seeking aesthetic procedures when compared with other populations or subjects with no interest in plastic surgery.22 Body dysmorphic disorder has been deemed the neuropsychiatric condition of greatest relevance to aesthetic procedures.5

In a systematic clinical review of the psychology of plastic surgery, the authors8 observed that narcissistic personality disorders, histrionic personality disorders, and BDD are the three most common psychiatric conditions in patients seeking aesthetic plastic surgery. One study9 found that 29.5% of the subjects diagnosed with BDD presented symptoms of narcissism. Other common personality traits of these patients include impulsivity, binge eating, and body discomfort.10

BDD signs and symptoms: on body and culture

Patients with BDD report concerns about up to five to seven body parts throughout the disorder, with some gender-related differences.11 Men are more likely to be disturbed by their genitals, body build, and hair loss resulting in baldness. In contrast, women are more affected by the disorder and tend to obsess about their skin, weight, breasts, buttocks, thighs, legs, hips, and excess body hair; in addition, they are excessively concerned with more body areas than men.23

The core symptom of BDD is body dissatisfaction, a category included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.2 There are several theories about the disorder’s origin, with genetics being a significant factor, since patients with a positive family history are four to eight times more likely to develop it. The search for aesthetic and surgical procedures to solve personal dissatisfaction, followed by restrictive diets and excessive physical exercise, are some peculiarities of these patients.12

Depression is the comorbidity most commonly associated with BDD, with a higher probability of persisting throughout the life of the patients, at a rate of 75%. Between 30 and 50% have reported alcohol or drug abuse, and most of these subjects stated that alcoholism and smoking had arisen as a result of BDD symptoms and associated clinical distress. The third most common comorbidity is social phobia, in 37 to 39% of the patients, followed by obsessive-compulsive disorder, in 32 to 33%. Phillips et al.,23 in a study with a sample of subjects with BDD, reported that only 9% of the patients had BDD alone, 22% had another associated mental disorder, 29% had 2 or more disorders, and 43% had 3 or more disorders in addition to BDD. The more comorbidities, the worse the quality of life of the patient.13

Throughout history, society has cultivated the body, aesthetics, and beauty differently depending on the era. As in the past, nowadays the culture through which human beings see the world completely influences their behavior. There is a defined standard, and those who do not meet it are seen as inferior to others. The search for ideal beauty is fluid and changeable over time and according to human needs, making this achievement always unfeasible. This concept of adequate physical appearance is often confused with feelings of happiness and satisfaction; therefore, many people see it as an indicator of success, either personal, professional, political, or cultural.12

Exposure to digital conferencing platforms has increased significantly, leading users to constantly check their appearance and find flaws in their perceived virtual appearance. Studies have shown that frequent use of social media can lead to an unrealistic and distorted body image, generating significant concern with appearance and high anxiety levels. In addition to social media exposure worsening body image dissatisfaction, it can also affect BDD comorbidities, such as depression and eating disorders.14

Diagnostic criteria and screening methods

The level of knowledge about one’s disorder is called insight, which is a significant diagnostic criterion.11 There are three insight levels: good, poor, or absent. If the patient is aware that the thoughts about their body are not true, it is a good insight. A poor insight occurs when the beliefs are probably deemed true. A patient with absent insight does not think they suffer from a disorder and has no awareness or control over their thoughts, being convinced that their beliefs are true. They report spontaneous intrusive thoughts, difficult to get out of the mind, and which intensify when they feel observed.2

These defects, associated with ideas of overvaluing body image and insufficient insight, become a clinical concern potentially resulting in significant morbidity, leading the patient to critical occupational and social losses.13 A study by Ribeiro15 found that 15.04% of plastic surgery patients have BDD (range: 2.21–56.67%); their average age was of 34.54 ± 12.41 years, and most were women (74.38%). Rabaioli et al.7 reported that surveys from the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS) revealed that Brazil is the country that ranks first in the world in terms of aesthetic surgical procedures. According to these studies,7 Brazil exceeds the number of plastic surgeries performed in the United States, which has been the world leader in recent years.

Preoperative psychological evaluation must be a central part of the initial plastic surgery visit.10 Although formal screening for BDD is not a common practice, the presence of the disorder is a relative contraindication for plastic surgery.16 Screening uses the Body Dysmorphic Disorder Questionnaire (BDDQ), which assesses the probability that the patient has BDD.17

Most sought-after procedures and risk of suicidal ideation and attempt

The most performed procedures to solve personal dissatisfaction are breast implants (15.3%), abdominal liposuction (13.9%), blepharoplasty (11.9%), liposculpture (9.1%), and rhinoplasty (8.2%).11,24,25,26 A study on the prevalence rates of BDD16 reported that candidates for abdominoplasty present the highest rate, 57%, followed by 52% of rhinoplasty patients, and 42% of rhytidoplasty patients. The severity of the BDD was significantly associated with the degree of body dissatisfaction, avoidance behaviors, sexual abuse, and suicidal ideation.16

In 2006, Phillips et al.23 reported that patients diagnosed with BDD presented high rates of suicidal ideation throughout their lives, of up to 78%. The worst prognoses were for patients attempting suicide, in 27.5% of cases.23 Reports of suicidal ideation were associated with greater comorbid depression throughout life.13

Treatment and postoperative dissatisfaction rate

Treating these patients is a challenge. They refuse to believe that they suffer from a mental disorder; therefore, cosmetic surgeries are prohibited, since no procedure will satisfy the subject, who suffers from a mental disorder. The most effective therapy for these patients is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). The first-line treatment is CBT, and patients report gaining greater insight into their appearance and improved quality of life. Adjuvant pharmacotherapy has proven effective in reducing symptoms related to concerns with appearance and compulsive behaviors, as well as the associated symptoms from depression and anxiety; it has also shown positive effects on social functioning, suicidal thoughts, and overall quality of life. However, further research is required to standardize the approach to these patients.6

A study on the evolution of subjects with minimal appearance defects 5 years after requesting cosmetic surgery28 confirmed that cosmetic surgery is not effective for patients with BDD, even when patients declared satisfaction, which may explain why some plastic surgeons do not fully adhere to surgical contraindications. Most studies show that performing cosmetic surgery rarely improves BDD symptoms, indicating that patients report a low degree of satisfaction and present deterioration of the symptoms of the disease, leading surgeons to promptly refer those screened for BDD to a psychiatrist familiar with the disorder.13

Despite the inability of any procedure to address their perceived flaws, patients often seek additional opinions and treatment options. In collaboration with legal counsel, warning signs are provided to recognize the disorder and critically evaluate informed consent and the legal ramifications of operating on these patients due to the high postoperative dissatisfaction.18 From a legal point of view, physicians must protect themselves from potential problems involving procedural outcomes and postoperative dissatisfaction. To do so, they must use several resources, since there are no laws or well-defined conducts to guide a legal dispute between a physician and a patient with BDD.6

Surgeons’ conduct

Identifying the psychologically-challenging patient before surgical intervention enables the subject to get adequate psychological assistance and may improve their health.5 It is up to the plastic surgeon to explain the possibilities and risks associated with surgery, to establish a good relationship with the patient, and to base their conduct on ethical principles and moral conscience.27

Among 265 plastic surgeons answering a questionnaire, 84% believed they had operated on a patient with BDD and, in only 1% of the cases, they thought that the procedure had brought benefits to the subject. In total, 40% of these doctors suffered some kind of threat, whether legal or physical, and more than 80% only discovered that the patient had BDD after the procedure. Among those who operated on a patient with BDD, 43% believed that the patient’s concern arose after the procedure, and 39% believed that concerns regarding other body parts appeared after surgery. There was a discrepancy between the perceived improvement by patients and the actual improvement in symptoms after cosmetic surgery, with 35% of the patients feeling better after the procedures, but only 1.3% reporting a decrease in symptoms after surgery. Most studies suggest that cosmetic surgery rarely improves BDD symptoms and may even be harmful to the patient.13

A study from 2019 revealed that mild to moderate BDD is not an exclusion criterion for cosmetic surgery, but it requires specific treatment planning and a multidisciplinary approach. Targeted screening, active and prudent discussion, knowledge of treatment options and special features of the disease pattern, fluctuating disorder understanding, and the desire for plastic surgery measures are strictly necessary. Caution becomes an essential medical quality, as it is not a cosmetic problem but a mental disorder, increasing overall patient satisfaction and decreasing the risk of litigation for surgeons.29,30,31

Conclusion

The prevalence of BDD, the most prominent disorder in patients currently undergoing plastic surgery, ranges from 2 to 50%. However, several studies hypothesize that these procedures rarely improve BDD symptoms and may even worsen the clinical picture, with high levels of surgical dissatisfaction.

The procedures most commonly sought by these patients are breast augmentation, abdominal liposuction, blepharoplasty, liposculpture, rhinoplasty, abdominoplasty, and rhytidoplasty. The severity of the case relies on the patient’s insight into their disorder and comorbidities, negatively affecting their quality of life. Although there is no way to prevent BDD, early diagnosis and treatment by a multidisciplinary team after the onset of symptoms is essential.

We conclude that, due the risk of worsening signs and symptoms and the high rate of surgical dissatisfaction, Brazil, the world champion in aesthetic plastic surgeries, must have its professionals trained to treat all healthy patients in plastic surgery, as well as assess the need for surgical cancellations in severe cases.

REFERENCES

1. Grant JE, Phillips KA. Recognizing and treating body dysmorphic disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2005;17(04):205–210

2. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5. Artmed Editora; 2014.

3. Phillips KA, Coles ME, Menard W, Yen S, Fay C, Weisberg RB. Suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in body dysmorphic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66(06):717–725

4. Sun MD, Rieder EA. Psychosocial issues and body dysmorphic disorder in aesthetics: Review and debate. Clin Dermatol 2022;40 (01):4–10

5. De Brito MJA, Nahas FX, Sabino Neto M. Invited Response on: Body Dysmorphic Disorder: There is an “Ideal” Strategy? Aesthetic Plast Surg 2019;43(04):1115–1116

6. Dornelas MT, Corrêa MDPD, Corrêa LD, et al. Body dysmorphic disorder from the perspective of the plastic surgeon. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (RBCP) – Brazilian Journal of Plastic Sugery 2019;34(01):118–122

7. Rabaioli L, Oppermann Pde O, Pilati NP, et al. Evaluation of postoperative satisfaction with rhinoseptoplasty in patients with symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2022;88(04):539–545

8. Shridharani SM, Magarakis M, Manson PN, Rodriguez ED. Psychology of plastic and reconstructive surgery: a systematic clinical review. Plast Reconstr Surg 2010; 126(06):2243–2251. https://journals.lww.com/plasreconsurg/Abstract/2010/12000/Psychology_of_Plastic_and_Reconstructive_Surgery_.59.aspx#:~:text=Narcissistic%20and%20histrionic%20personality%20disorders

9. Sahraian A, Janipour M, Tarjan A, Zareizadeh Z, Habibi P, Babaei A. Body Dysmorphic and Narcissistic Personality Disorder in Cosmetic Rhinoplasty Candidates. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2022;46(01): 332–337

10. Pavan C, Marini M, De Antoni E, et al. Psychological and Psychiatric Traits in Post-bariatric Patients Asking for Body-Contouring Surgery. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2017;41(01):90–97. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28032161/

11. Watzke B, Rufer M, Drüge M. Die körperdysmorphe Störung: Diagnostik, Behandlung und Herausforderungen in der hausärztlichen Praxis. Praxis (Bern) 2020;109(07):492–498

12. Coelho FD, de Carvalho PHB, Paes ST, Ferreira MEC. Esthetic plastic surgery and (in) satisfaction index: a current view. Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (RBCP) – Brazilian Journal of Plastic Sugery 2017;32(01):135–140. Available from http://rbcp.org.br/export-pdf/1824/v32nlal9.pdf cited 2022 May 29

13. Harðardóttir H, Hauksdóttir A, Björnsson AS. Líkamsskynjunarröskun: Helstu einkenni, algengi, greining og meðferð. Laeknabladid 2019;(03):125–131. Available from https://www.laeknabladid.is/media/tolublod/1844/PDF/f02.pdf

14. Laughter MR, Anderson JB, Maymone MBC, Kroumpouzos G. Psychology of aesthetics: Beauty, social media, and body dysmorphic disorder. Clin Dermatol 2023;41(01):28–32

15. Ribeiro RVE. Prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Plastic Surgery and Dermatology Patients: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2017;41(04):964–970

16. Houschyar KS, Philipps HM, Duscher D, et al. [The Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Plastic Surgery - A Systematic Review of Screening Methods]. Laryngorhinootologie 2019;98(05):325–332. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31618775/

17. Joseph AW, Ishii L, Joseph SS, et al. Prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Surgeon Diagnostic Accuracy in Facial Plastic and Oculoplastic Surgery Clinics. JAMA Facial Plast Surg 2017;19(04): 269–274. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamafacialplastic-surgery/fullarticle/2588842

18. de Brito MJA, Nahas FX, Cordás TA, Tavares H, Ferreira LM. Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Patients Seeking Abdominoplasty, Rhinoplasty, and Rhytidectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016; 137(02): 462–471

19. Morselli PG, Micai A, Boriani F. Eumorphic Plastic Surgery: Expectation Versus Satisfaction in Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2016;40(04):592–601

20. Raeissosadati NS, Javan Bakht M, Sharifi Z, Behgam N, Sanjar Moussavi N. Comparison of Frequency of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Applicants of Abdominoplasty with Applicants of Other Cosmetic Surgeries. World J Plast Surg 2022; 11(02): 101–195. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36117888/cited2023Jun10

21. Ramos TD, de Brito MJA, Suzuki VY, Sabino Neto M, Ferreira LM. High Prevalence of Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Moderate to Severe Appearance-Related Obsessive-Compulsive Symptoms Among Rhinoplasty Candidates. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2019;43 (04):1000–1005

22. Kuhn H, Cunha PR, Matthews NH, Kroumpouzos G. Body dysmorphic disorder in the cosmetic practice. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2018;153(04):506–515

23. Phillips KA, Menard W, Fay C. Gender similarities and differences in 200 individuals with body dysmorphic disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2006;47(02):77–87

24. Siegfried E, Ayrolles A, Rahioui H. L’obsession de dysmorphic corporelle: perspectives d’évolution de la prise en charge. Encephale 2018;44(03):288–290. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0013700617301811

25. Sucupira E, De Brito M, Leite A, Aihara E, Neto MS, Ferreira L. Body Dysmorphic Disorder and Personality in Breast Augmentation: The Big-Five Personality Traits and BDD Symptoms. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2022;75(09):3101–3107

26. Huayllani MT, Eells AC, Forte AJ. Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Plastic Surgery: What to Know When Facing a Patient Requesting a Labiaplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg 2020;145(02):468e–469e

27. Hostiuc S, Isailă OM, Rusu MC, Negoi I. Ethical Challenges Regarding Cosmetic Surgery in Patients with Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Healthcare (Basel) 2022;10(07):1345

28. Tignol J, Biraben-Gotzamanis L, Martin-Guehl C, Grabot D, Aouiz-erate B. Body dysmorphic disorder and cosmetic surgery: evolution of 24 subjects with a minimal defect in appearance 5 years after their request for cosmetic surgery. Eur Psychiatry 2007;22 (08):520–524. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0924933807013326

29. Sweis IE, Spitz J, Barry DR Jr, Cohen M. A Review of Body Dysmorphic Disorder in Aesthetic Surgery Patients and the Legal Implications. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2017;41(04):949–954

30. Kataoka A, Lage RR, Mendes CCS, Soares NG. O Transtorno Dismórfico Corporal e a influência da mídia na procura por cirurgia plástica: a importância da avaliação adequada. Rev Bras Cir Plást 2023;38:e0645. Available from https://www.scielo.br/j/rbcp/a/RnRbXNdhYQKvyzzCghRkRJr/?lang=pt

31. Behar R, Arancibia M, Heitzer C, Meza N. Trastorno dismórfico corporal: aspectos clínicos, dimensiones nosológicas y controversias con la anorexia nerviosa. Rev Med Chil 2016;144(05):626–633

1. Medicine Program, Universidade do Contestado,

Mafra, SC, Brazil

Address for correspondence Simone Kempf Stachechem, , Curso de Medicina, Universidade do Contestado, Mafra, SC, Brazil (e-mail: simonestachechem@gmail.com; simone.stachechem@aluno.unc.br).

Article received: January 24, 2024.

Article accepted: September 29, 2024.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter