Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Happiness of plastic surgeons in São Paulo, Brazil: A cross-sectional study of the Brazilian Plastic Surgery Society - SBCP-SP

Felicidade dos cirurgiões plásticos em São Paulo, Brasil: Um estudo transversal entre os membros da Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica - SBCP-SP

ABSTRACT

Introduction: The career of the surgeon is challenging, and scientific research has identified a prevalence of burnout in approximately 1/3 of plastic surgeons. The data on well-being and factors associated with greater happiness available specifically to plastic surgery are inconsistent and limited. The objective is to evaluate the happiness of plastic surgeons in São Paulo and which factors are associated with greater happiness.

Method: This was a primary, observational, descriptive, and cross-sectional study. An online survey was conducted using a validated instrument, the Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS), which was sent to members of the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery-São Paulo (SBCP-SP) from December 2020 to July 2021. Sociodemographic and occupational characteristics were related to the degree of happiness measured.

Results: The response rate was 12.18%, n = 268, with 70.1% males and 29.9% females. The score obtained using the SHS was 5.51 ± 0.13, and the mean score for males was 5.49 and for females was 5.57. A total of 143 (53.36%) of the participants were associate members, and 125 (46.64%) were full members of the SBCP. A total of 177 (66.04%) stated that if they could go back in time, they would choose plastic surgery again as a specialty, 62 (23.13%) perhaps, and 27 (10.82%) said that they would not.

Conclusion: Plastic surgery in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, allows professionals in the specialty to have a career with high levels of happiness, including for females.

Keywords: Surgery, Plastic; Happiness; Personal Satisfaction; Internship and Residency; Quality of Life

RESUMO

Introdução: A carreira do cirurgião é desafiadora, pesquisas científicas identificaram uma prevalência de burnout em cerca de 1/3 dos cirurgiões plásticos. Estudos científicos anteriores sobre esse tópico têm se concentrado nos aspectos negativos do trabalho na área médica. Os dados de bem-estar e dos fatores associados à maior felicidade disponíveis, específicos para cirurgia plástica, são inconsistentes e limitados. O objetivo é avaliar a felicidade do cirurgião plástico do estado de São Paulo e quais fatores estão associados à maior felicidade.

Método: Estudo primário, observacional, descritivo e transversal. Foi realizada uma pesquisa on-line utilizando um instrumento validado, a Escala de Felicidade Subjetiva (EFS), que foi enviado aos membros da Regional São Paulo da Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP-SP) entre dezembro de 2020 e julho de 2021. Características sociodemográficas e ocupacionais foram relacionadas ao grau de felicidade mensurado.

Resultados: A taxa de resposta foi de 12,18%, n=268, sendo 70,1% do sexo masculino e 29,9% do feminino. O escore obtido através da EFS foi de 5,51±0,13 e a média do escore para o sexo masculino foi de 5,49 e para o sexo feminino de 5,57. 143 (53,36%) dos participantes são membros associados e 125 (46,64%) membros titulares da SBCP. 177 (66,04%) afirmaram que, caso pudessem voltar atrás, escolheriam novamente a cirurgia plástica como especialidade, 62 (23,13%) que talvez, e 27 (10,82%) que não.

Conclusão: A cirurgia plástica no estado de São Paulo, Brasil, possibilita aos profissionais da especialidade uma carreira com altos índices de felicidade, inclusive para o sexo feminino.

Palavras-chave: Felicidade; Qualidade de vida; Cirurgia Plástica; Internato e residência; Satisfação pessoal

INTRODUCTION

The well-being of the physician has gained significant international attention in recent years, actively fueling the change in policies regarding their working conditions.1 The routine of the physician, especially the surgeon, remains challenging, with prolonged and unpredictable working hours, stress from emotionally difficult situations, and demands to master surgical techniques. Burnout, described as emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and low personal accomplishment, has been associated with a decrease in quality of life and an increase in professional errors.2

A recent study conducted with American plastic surgeons concluded that, despite the high prevalence of burnout and mental health disorders associated with a career in medicine, American plastic surgeons have high levels of happiness.1 Although this study focused on the positive aspects of the medical profession, studies investigating happiness in medicine and, especially, plastic surgery are limited.2 The scarcity of data is even more evident in developing countries, such as Brazil, the country with the second largest number of plastic surgeons in the world, and a country that presents a different reality from that of developed countries.

The objective of this study was to specifically evaluate the happiness of plastic surgeons belonging to the Brazilian Society of Plastic Surgery – São Paulo – SBCP-SP, and to evaluate which factors are associated with greater happiness.

METHODS

This was a primary, observational, cross-sectional, descriptive study conducted in a single center.

The project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CEP) of the Universidade Federal de São Paulo/Escola Paulista de Medicina (Unifesp/EPM), under number 35395220.9.0000.5505. The project was also approved by the Board of the Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica -São Paulo, which provided the members’ e-mail addresses, and conducted between October 2020 and October 2022. The data were kept confidential and anonymized to comply with the General Data Protection Law of Brazil (LGPD).

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist3, the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES)4 and the Survey Disclosure Checklist (American Association for Public Opinion Research, AAPOR) were used to describe the study.5

The sample size of 238 participants was calculated considering a significance level of 5% (95% confidence interval), 6% accuracy and the population size of 2,200 plastic surgeon members of the Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica São Paulo Regional.

The inclusion criteria adopted were associate members and full members of the Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP) São Paulo Regional who had their e-mail updated in the SBCP database.

The non-inclusion criteria were associate members or full members of the SBCP who did not agree to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria adopted were associate members or full members of the SBCP who, after reviewing the questionnaire, decided to withdraw their authorization to participate in the study.

To characterize the casuistry, sociodemographic and professional data were obtained and elaborated with the collaboration of a multidisciplinary team composed of psychologists, psychiatrists, and plastic surgeons. The questionnaire was prepared following the recommendations of CHOI & PAK (2005)6 and CHUNG et al.7 and sent to members via e-mail containing the consent form and a link to the Google Forms® survey.

Data collection occurred from December 27, 2020, to July 28, 2021. The invitation was sent six times, and the response rate was calculated based on the total number of responses and the number of invited participants. The descriptive analysis of those who did not respond was not performed, and participants who may have given up answering after reading the questions or after partially answering the questions were not identified. For the participants who agreed to participate, all questions were mandatory so that the form could be authorized for submission, and all responses received were included in the results.

The instrument used to assess happiness was the SHS questionnaire developed by Lyubomirsky and Lepper.8 This instrument was translated and validated for Brazilian Portuguese.9 The scores range from 1.0 to 7.0, with higher scores reflecting greater happiness.

RESULTS

The data were subjected to descriptive and inferential statistical analysis. Regarding the descriptive statistics, for the description of the quantitative variables, the mean was used as a measure of dispersion, and the variability was determined by the standard deviation; for the qualitative (or categorical) variables, the absolute (n) and relative (%) frequency of the studied events were used. Regarding inferential statistics, nonparametric tests were used. The degree of association between the two variables was assessed using Spearman’s correlation. The Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare two-by-two variables from independent samples, and in the comparisons between more than two subgroups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was used. The information was recorded in a database using Microsoft Office Excel (2016) and statistically analyzed using IBM SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, version 20.0) and MINITAB16. The significance level adopted for all analyses was 5%.

The response rate was 12.18%. A total of 268 participants completed the form, and there was no request for exclusion from participation. Among the participants, 188 were male (70.1%), and 80 were female (29.9%). The score obtained using the SHS scale was 5.51 ± 0.13.

The correlation between the happiness score and the three questions that evaluated quantitative factors is shown in Table 1, and there was a statistically significant correlation between two of them.

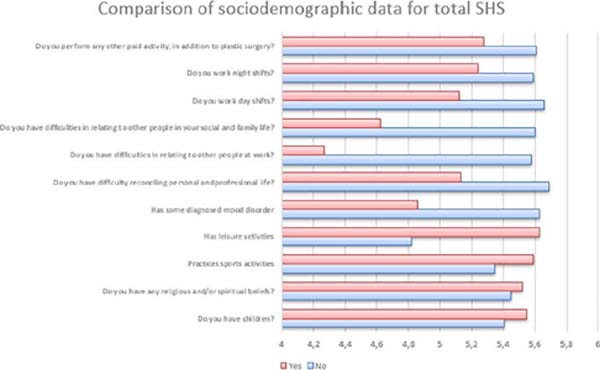

The relationships between happiness scores and sociodemographic data are shown in Table 2 and illustrated in Figures 1 and 2.

| N | Mean | Standard Deviation | CI | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 80 (29.85%) | 5.57 | 1.13 | 0.25 | 0.549 |

| Male | 188 (70.15%) | 5.49 | 1.11 | 0.16 | ||

| Marital status | With partner | 237 (88.43%) | 5.47 | 1.12 | 0.14 | 0.090 |

| Without partner | 31 (11.57%) | 5.84 | 1.03 | 0.36 | ||

| Do you have children? | No | 77 (28.73%) | 5.41 | 1.05 | 0.23 | 0.213 |

| Yes | 191 (71.27%) | 5.55 | 1.14 | 0.16 | ||

| Do you have any religious and/or spiritual beliefs? | No | 31 (11.57%) | 5.45 | 1.21 | 0.43 | 0.881 |

| Yes | 237 (88.43%) | 5.52 | 1.10 | 0.14 | ||

| Practices sports activities | No | 83 (30.97%) | 5.35 | 1.22 | 0.26 | 0.234 |

| Yes | 185 (69.03%) | 5.59 | 1.06 | 0.15 | ||

| Has leisure activities | No | 38 (14.18%) | 4.82 | 1.33 | 0.42 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 230 (85.82%) | 5.63 | 1.03 | 0.13 | ||

| Has some diagnosed mood disorder | No | 228 (85.07%) | 5.63 | 1.05 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 40 (14.93%) | 4.86 | 1.27 | 0.39 | ||

| Do you have difficulty reconciling personal and professional life? | No | 185 (69.03%) | 5.69 | 1.02 | 0.15 | 0.001 |

| Yes | 83 (30.97%) | 5.13 | 1.21 | 0.26 | ||

| Do you have difficulties relating to other people at work? | No | 254 (94.78%) | 5.58 | 1.07 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 14 (5.22%) | 4.27 | 1.11 | 0.58 | ||

| Do you have difficulties relating to other people in your social and family life? | No | 243 (90.67%) | 5.60 | 1.05 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 25 (9.33%) | 4.62 | 1.33 | 0.52 | ||

| Do you work day shifts? | No | 196 (73.13%) | 5.66 | 1.07 | 0.15 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 72 (26.87%) | 5.12 | 1.15 | 0.27 | ||

| Do you work night shifts? | No | 207 (77.24%) | 5.59 | 1.08 | 0.15 | 0.042 |

| Yes | 61 (22.76%) | 5.24 | 1.20 | 0.30 | ||

| Do you perform any other paid activity, in addition to plastic surgery? | No | 189 (70.52%) | 5.61 | 1.06 | 0.15 | 0.040 |

| Yes | 79 (29.48%) | 5.28 | 1.21 | 0.27 | ||

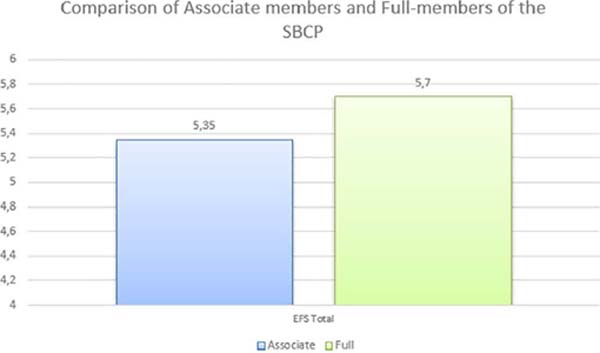

| You are a member of the SBCP | Associate Full-member (Titular) | 143 (53.36%) | 5.35 | 1.20 | 0.20 | 0.031 |

| 125 (46.64%) | 5.70 | 0.98 | 0.17 | |||

| Number of hours worked per week? | Less than 60 hours Entre 60 e 80 horas More than 80 hours | 104 (38.81%) | 5.52 | 1.15 | 0.22 | 0.077 |

| 129 (48.13%) | 5.40 | 1.12 | 0.19 | |||

| 35 (13.06%) | 5.91 | 0.86 | 0.29 | |||

| Type of surgery performed | Both | 212 (79.1%) | 5.54 | 1.08 | 0.15 | 0.795 |

| Aesthetics | 47 (17.54%) | 5.41 | 1.30 | 0.37 | ||

| Reconstructive | 9 (3.36%) | 5.39 | 0.89 | 0.58 | ||

| Do you consider that your professional career as a plastic surgeon has reached a satisfactory level of stability? | No | 86 (32.09%) | 4.96 | 1.16 | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 143 (53.36%) | 5.85 | 1.00 | 0.16 | ||

| Perhaps | 39 (14.55%) | 5.51 | 0.91 | 0.29 | ||

| If you could go back, would you choose plastic surgery as a career again? | No | 29 (10.82%) | 4.37 | 1.21 | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Yes | 177 (66.04%) | 5.87 | 0.90 | 0.13 | ||

| Perhaps | 62 (23.13%) | 5.02 | 1.07 | 0.27 | ||

| Location of activity | Capital | 150 (55.97%) | 5.64 | 1.15 | 0.18 | 0.017 |

| Interior | 118 (44.03%) | 5.36 | 1.05 | 0.19 |

Groups were divided and compared according to age group and time of completion of residence (Table 3), with no statistically significant differences.

| Standard | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | Deviation | IC | Valor-p | ||

| Age range | Up to 40 years ≥ 41 years | 88 (32.84%) | 5.49 | 1.13 | 0.24 | 0.767 |

| 180 (67.16%) | 5.53 | 1.11 | 0.16 | |||

| Residence time | Up to 10 years | 98 (36.57%) | 5.44 | 1.17 | 0.23 | |

| 88 (32.84%) | 11 to 20 years | 80 (29.85%) | 5.41 | 1.13 | 0.25 | 0.255 |

| 180 (67.16%) | ||||||

| ≥ 21 years | 90 (33.58%) | 5.69 | 1.02 | 0.21 | ||

DISCUSSION

There are few studies in the literature that aim to evaluate the happiness of plastic surgeons. In 1997, Capek et al.10 applied a questionnaire to American plastic surgeons and reported a high level of happiness and satisfaction with their careers, similar to the results found in this study.

More recently, Streu et al.11 in 2014 and Qureshi et al.12 in 2015 demonstrated that American plastic surgeons have a lower quality of life than the American population in general. The concepts of quality of life and happiness are distinct. Considering that the objective of this study was to specifically evaluate happiness, it is not possible to compare the results of these American studies with the present study.

More recently, Sterling et al.1 evaluated the happiness of American plastic surgeons using the same scale used in this study. The researchers observed that there was an increase in happiness as they progressed in training and that meeting the expectations of the practice after training also correlated with higher happiness rates.

In Brazil, similar studies evaluating happiness were not found, but two published studies aimed to understand the sociodemographic characteristics of plastic surgeons and were each restricted to states with a relatively low number of plastic surgeons: Paraná and Goiás. In the first, Araújo et al.13 only described sociodemographic characteristics, and in the second, Arruda et al.14 correlated the sociodemographic data with quality of life. In the latter, the authors concluded that factors such as being married, having children, having a monthly income greater than R $ 30,000.00, working time greater than 10 years, being at least a specialist, not working shifts, having a weekly workload of up to 40 hours, and performing more than 4 surgeries per week positively influence a better quality of life.

São Paulo, the focus of the present study, includes at least one-third of the plastic surgery specialists in Brazil,15 and had an SHS score of 5.51 ± 0.13. Although the economic realities of Brazil and the United States are quite different, such data suggest that plastic surgeons in the state of São Paulo report a level of happiness similar to that of Americans, which was 5.5.1

Arruda et al.14 found that better quality of life was associated with married plastic surgeons who had children, while in the present study, there was no difference between the happiness of those who had or did not have partners and those who did or did not have children. In this regard, Sterling et al.1 also found no statistically significant differences in the happiness levels of American surgeons.

In a specialty with male predominance, it would be plausible to assume that women would face greater challenges and that they would report lower levels of happiness. However, the results of the present study did not observe a difference in the levels of happiness between the sexes, demonstrating a scenario similar to that of the United States1.

Among medical students, there is a tendency to think that cosmetic plastic surgery may be a more interesting career than reconstructive plastic surgery. However, the results of the present study found no difference between the levels of happiness between surgeons who practice cosmetic and reconstructive surgery. Such data may be useful for the Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP) to encourage the specialty of reconstructive surgery not only in the state of São Paulo but also throughout the country.

In this study, the majority (66%) of plastic surgeons stated that if they could go back, they would choose the specialty of plastic surgery again, and only 10.8% stated the opposite. This is an encouraging finding, especially for future aspirants in this career, who may have doubts about their choice of specialty.

This study has limitations. As a descriptive, cross-sectional study, the results refer only to a certain time, and some responses may have been influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is necessary to take into account that some of the questions in the questionnaire are sensitive and may have caused some of the participants to feel uncomfortable answering them. There is the possibility of selection bias, where the population that agreed to participate in the study and answered the questionnaire is substantially different from the population that did not choose to participate.

On the other hand, the present study has, as positive points, following the checklist Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE),3 the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES)4 and the Survey Disclosure Checklist (American Association for Public Opinion Research/AAPOR)5. In addition, although the response rate may be considered low, it is compatible with the rates reported by surveys conducted using electronic means16 and reached the targeted sample size. A prospective study, following a cohort of Brazilian plastic surgeons throughout their careers, would allow a better understanding of the happiness of plastic surgeons, how it can change over time, and which factors are most influential.

CONCLUSION

The plastic surgeon in São Paulo has a level of happiness similar to that reported by American surgeons, with no differences in happiness between the sexes or between those who work in aesthetics, reconstructive, or both.

REFERENCES

1. Sterling DA, Grow JN, Vargo JD, Nazir N, Butterworth JA. Happiness in Plastic Surgery: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of 595 Practicing Plastic Surgeons, Fellows, Residents, and Medical Students. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;84(1):90-4.

2. Pulcrano M, Evans SR, Sosin M. Quality of Life and Burnout Rates Across Surgical Specialties: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(10):970-8.

3. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. T The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1453-7.

4. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: The Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34.

5. https://www.aapor.org/Standards-Ethics/AAPOR-Code-of- Ethics/Survey-Disclosure-Checklist.aspx

6. Choi BC, Pak AW. A catalog of biases in questionnaires. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(1):A13.

7. Chung WHJ, Gudal RA, Nasser JS, Chung KC. Critical Assessment of Surveys in Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery: A Systematic Review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(5):912e-22e.

8. Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indic Res. 1999;46:137-55.

9. Damasio B F, Zanon C, Koller SH. Validation and psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the subjective happiness scale. Univ Psychol. 2014;13(1):17-24.

10. Capek L, Edwards DE, Mackinnon SE. Plastic surgeons: a gender comparison. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(2):289-99.

11. Streu R, Hansen J, Abrahamse P, Alderman AK. Professional burnout among US plastic surgeons: results of a national survey. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72(3):346-50.

12. Qureshi HA, Rawlani R, Mioton LM, Dumanian GA, Kim JYS, Rawlani V. Burnout phenomenon in U.S. plastic surgeons: risk factors and impact on quality of life. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135(2):619-26.

13. Araujo LRR, Auersvald A, Gamborgi MA, Freitas RS. Perfil do cirurgião plástico paranaense. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2012;27(3 Suppl.1):12.

14. Arruda FC, Paula PR, Porto CC. Quality of Life of the Plastic Surgeon in the Midwest of Brazil. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2018;6(8):e1802.

15. Sociedade Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica (SBCP). 2020. Demografia Cirurgia Plástica. Número de cirurgiões plásticos e perfil geoeconômico por município. [Acesso 2021 Ago 7]. Disponível em: http://www2.cirurgiaplastica.org.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/demografia_cirurgiaplastica_2020_alta.pdf

16. Thoma A, Cornacchi SD, Farrokhyar F, Bhandari M, Goldsmith CH; Evidence-Based Surgery Working Group. How to assess a survey in surgery. Can J Surg. 2011;54(6):394-402.

1. Universidade Nove de Julho - Vergueiro Campus,

Brazil - SP., - - São Paulo - São Paulo - Brazil.

2. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Plastic

Surgery Division - São Paulo - São Paulo - Brazil.

3. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Discipline

of Operative Technique and Experimental Surgery - São Paulo - São Paulo -

Brazil.

Corresponding author: Marcio Yuri Ferreira Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola Paulista de Medicina Rua Botucatu, 740, Vila Clementino, São Paulo, S P, Brazil. CEP: 04023-062 E-mail: secretaria.sp@unifesp.br

Article received: March 21, 2024.

Article accepted: April 30, 2024.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter