Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 - Issue 3

Temporal trend, regional distribution and profile of morbidity and mortality due to childhood burns in Santa Catarina: An ecological study

Tendência temporal, distribuição regional e perfil da morbimortalidade por queimadura na infância em Santa Catarina: Um estudo ecológico

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Burns is a public health challenge due to high morbidity and mortality and impairment of the victim's quality of life. They disproportionately affect populations of lower socioeconomic status, resulting in high health costs.

Method: Ecological, retrospective, observational study, with a quantitative approach and temporal trend analysis of morbidity and mortality due to burns in Santa Catarina, with data obtained from the Hospital and Mortality Information Systems made available by the Information Technology Department of the Unified Health System. Temporal analysis by Spearman Correlation Test.

Results: There was a growing trend in the general hospitalization rate (Spearman=0.806; p<0.005) for burns in the state in the period analyzed. Higher prevalence in males (RP 1.68), in the population aged 0 to 4 years (RP 3.08), and in the Greater Florianópolis region (mean rate 23.22%). The group classified as medium burn predominated (mean rate 25.67%) and hospitalizations of 0 to 3 days (mean rate 50.25%). Burns to the head, neck, and trunk (mean rate 32.25%) were the most prevalent.

Conclusion: A growth trend was identified in the hospitalization rate for burns in children in the state. Higher prevalence of hospitalization in males, in children aged 0 to 4 years, and in the Greater Florianópolis region. Predominance of moderate burns and burns to the head, neck, and trunk, with a higher rate of short-term hospitalizations.

Keywords: Burns; Hospitalization; Child; Body surface area; Indicators of morbidity and mortality

RESUMO

Introdução: As queimaduras são um desafio da saúde pública devido à alta morbimortalidade e prejuízo na qualidade de vida da vítima. Elas afetam desproporcionalmente as populações de menor nível socioeconômico, resultando em elevados custos para saúde.

Método: Estudo ecológico, retrospectivo, observacional, com abordagem quantitativa e análise de tendência temporal da morbimortalidade por queimadura em Santa Catarina, com dados obtidos dos Sistemas de Informações Hospitalar e de mortalidade disponibilizados pelo Departamento de Informática do Sistema Único de Saúde. Análise temporal pelo Teste de Correlação de Spearman.

Resultados: Verificada tendência de crescimento na taxa geral de internação (Spearman=0,806; p<0,005) por queimaduras no estado no período analisado. Maior prevalência no sexo masculino (RP 1,68), na população de 0 a 4 anos (RP 3,08) e na região da Grande Florianópolis (taxa média 23,22%). Predominou o grupo classificado como médio queimado (taxa média 25,67%) e as internações de 0 a 3 dias (taxa média 50,25%). Queimaduras em cabeça, pescoço e tronco (taxa média 32,25%) foram as mais prevalentes.

Conclusão: Identificada tendência de crescimento na taxa de internação por queimaduras em crianças no estado. Maior prevalência de internação no sexo masculino, em crianças de 0 a 4 anos e na região da Grande Florianópolis. Predomínio de médio queimados e de queimaduras em cabeça, pescoço e tronco, com maior taxa de internações de curta duração.

Palavras-chave: Queimaduras; Hospitalização; Criança; Superfície corporal; Indicadores de morbimortalidade

INTRODUCTION

Burns are an important global public health problem, due to their high morbidity and mortality and frequent impairment of victims’ mental health and quality of life1,2,3,4. In Brazil, approximately one million people suffer some type of burn every year, making this injury one of the most frequent external causes of mortality2. Around 50% of cases occur in domestic environments, and the most affected age group is children under 5 years old2.

Traumas that cause tissue injuries due to heat can be of radioactive, electrical, chemical, or thermal origin, the latter, which includes exposure to flames and superheated liquids, being the form most involved in accidents involving younger children5,6. These lesions can occur at different depths in the epithelial layer, divided into first-degree (superficial), second-degree (partial thickness), and third-degree (full thickness)5. Among the main causes of hospitalization due to burns, the most common is scalding, followed by fire and explosion accidents, with fire being the main cause of mortality among these patients7,8,9.

It is important to highlight the factors related to a higher mortality rate in patients with burns, such as greater burned body surface area, advanced age, and female sex10. A study carried out by Barcellos et al.7 showed that 80% of patients with more than 50% of body surface burned died. Another aspect associated with a greater risk of death is the presence of inhalation injury, which, when present, must be promptly diagnosed and treated.

Another common complication is sepsis, which is also associated with higher mortality10. Pediatric patients who have more than 15% of their body surface burned can develop Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. In these cases, to prevent shock and death, adequate intravenous fluid resuscitation is essential. It is worth noting that children have a lower volume of circulating blood concerning the body surface, therefore, immediate volume replacement is very important11.

The high prevalence of burn cases is reflected in high costs for the health sector both in Brazil and in other countries12. Therefore, knowing the regional peculiarities associated with cases of burns in childhood is important to understand the distribution, evolution, and outcomes of this important cause of morbidity and mortality in our country.

OBJECTIVE

The study aims to analyze the temporal trend and epidemiological profile of hospital morbidity and mortality due to burns in children aged 0 to 9 years in Santa Catarina from 2012 to 2021, considering sociodemographic variables (gender, age, macro-region of residence) and aspects of clinical assessment of burns in children (area of the body affected, degree of burn, mortality).

METHOD

Ecological observational study, with a quantitative approach and temporal trend analysis. The population studied was children aged 0 to 9 years, living in Santa Catarina, who were hospitalized or died as a result of burns, registered in the databases of the information systems of the Department of Informatics of the Unified Health System (DATASUS).

Based on data from the SUS Hospital Information System (SIH-SUS), the population associated with the 3,900 hospitalizations and 10 deaths that occurred in the state of Santa Catarina during the period studied was obtained, comprising hospitalizations between January 2012 and December 2021 whose basic cause of hospitalization was chapter XIX (Injuries, poisonings and some other consequences of external causes) of the International Classification of Diseases - ICD-10th Revision, codes T20 to T32, which correspond to the grouping of injuries due to burns and corrosion. The state of Santa Catarina was divided into seven health macro-regions, namely: South, Planalto Norte and Nordeste, Meio Oeste and Serra Catarinense, Grande Oeste, Grande Florianópolis, Foz do Rio Itajaí and Alto Vale do Itajaí.

The data were extracted and tabulated with the help of the Tabwin tool, made available by DATASUS, and transformed into coefficients or incidence rates calculated using as the numerator the total number of hospitalizations for burns according to the dependent variables (gender, age group, and macro-region of residence, extension of burn, body region affected and death), and as the denominator the population of children aged 0 to 9 years living in Santa Catarina in each year studied.

The result of this division was multiplied by the constant 100,000. The mortality rate was calculated using the total number of hospital deaths as the numerator, and the denominator being the population of children aged 0 to 9 years living in Santa Catarina in each year studied. The result of this division was multiplied by the constant 100,000. The lethality rate considered the total number of hospital deaths as the numerator and the total number of hospitalizations due to burns in children aged 0 to 9 years living in Santa Catarina in the studied period as the denominator. The result of this division was multiplied by 100.

The absolute frequency of the variables length of stay and need for ICU admission were transformed into proportions (%), considering in the numerator the total number of hospitalizations according to the dependent variables (length of stay in days and need for admission to the Intensive Care Unit), and as the denominator, the total number of hospitalizations of children aged 0 to 9 years in Santa Catarina in the period studied.

The series of risk rates and proportions obtained were submitted to a time-event correlation analysis model using SPSS version 20.0 software based on the calculation of the Spearman correlation coefficient, the mean annual variation (Beta) calculated by simple linear regression, and statistical significance based on the calculation of the p-value using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) method. Values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Immediate (hospital) mortality rates considered the death outcomes of hospitalizations due to burns, and fatality rates considered the total number of hospitalizations due to burns studied as the denominator.

The study complied with the ethical precepts of the National Health Council, in its Resolutions No. 466/2012 and No. 510/2016, and, as it was secondary data, in the public domain, it was not necessary to evaluate the ethics committee in search.

RESULTS

Between 2012 and 2021, 3,900 hospitalizations due to burns were recorded by the Unified Health System in Santa Catarina. Table 1 presents trends in hospitalization rates according to gender (male and female) and age (0 to 4 years and 5 to 9 years). Concerning sex, hospitalizations for burns in Santa Catarina indicated a temporal trend of growth, both in males and females (Spearman=0.758; p-value=0.010, and Spearman=0.685; p-value=0.029, respectively). The mean prevalence ratio (PR) for males was 1.68 admissions for every female admission in the period studied.

| Year | M | Fem | 0-4 years | 5-9 years | SC | Tx. Mort. | Tx. Lethal. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 33.40 | 22.38 | 37.81 | 18.84 | 28.01 | 0.78 | 7.81 |

| 2013 | 37.66 | 23.40 | 49.94 | 12.59 | 30.69 | 1.08 | 10.75 |

| 2014 | 52.51 | 28.24 | 60.04 | 22.34 | 40.65 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2015 | 45.11 | 34.02 | 65.36 | 15.34 | 39.69 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2016 | 61.99 | 30.71 | 64.30 | 29.95 | 46.70 | 0.48 | 4.76 |

| 2017 | 52.98 | 39.45 | 75.79 | 18.29 | 46.36 | 0.24 | 2.40 |

| 2018 | 70.34 | 45.02 | 88.01 | 29.26 | 57.97 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2019 | 65.87 | 31.14 | 72.12 | 26.70 | 48.90 | 0.23 | 2.29 |

| 2020 | 56.99 | 29.59 | 72.02 | 16.44 | 43.60 | 0.26 | 2.57 |

| 2021 | 58.85 | 43.66 | 88.49 | 16.03 | 51.43 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Mean Tx | 47.69 | 28.39 | 58.54 | 18.97 | 38.26 | 0.31 | 2.56 |

| Spearman | 0.758 | 0.685 | 0.879 | 0.091 | 0.806 | -0.188 | -0.420 |

| Beta | 0.767 | 0.684 | 0.875 | 0.160 | 0.800 | -0.587 | -0.582 |

| p-value | 0.010 | 0.029 | 0.001 | 0.660 | 0.005 | 0.074 | 0.077 |

Technical notes: Fem = Feminine; SC = Santa Catarina; Tx Mort. = Mortality Rate; Tx. Lethal. = Fatality Rate; Spearman = Correlation test; Beta = Mean annual variation by regression (cases/100,000 inhabitants/year); p-value = ANOVA. Tx Mort = number of deaths from burns/population 0-9 years*100,000; Tx let = (total number of hospital deaths/number of hospitalizations due to burns x100).

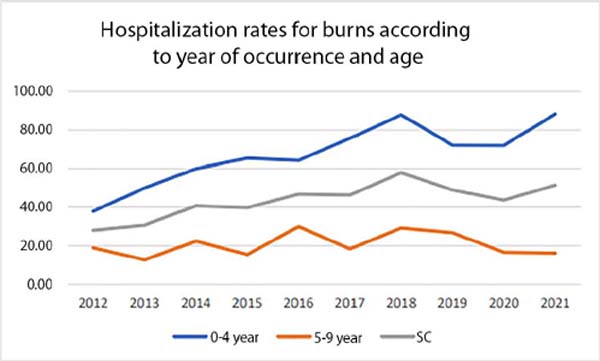

As seen in Table 1 and Figure 1, hospitalization rates for burns in the age group from 0 to 4 years also showed an important growth trend (Spearman=0.879; p-value=0.001), while rates from 5 to 9 years showed a tendency towards stability (Spearman=0.091; p-value=0.660). The prevalence was higher in the population aged 0 to 4 years (RP=3.08).

Hospitalization rates for burns across the state indicated growth in the period (Spearman=0.806; p-value=0.005). The hospital mortality rate from burns was 0.3/100,000, with a tendency towards stability. The annual fatality rate (x1,000) of hospitalizations due to burns in SC ranged from 0 to 10.75 deaths/1,000 hospitalizations. It is worth noting that in four of the ten years studied, no deaths were recorded. The mean fatality rate in the period was 2.56 deaths/1,000 hospitalizations.

Table 2 presents hospitalization rates for burns according to the macro-regions of the state of Santa Catarina. The results obtained indicated a general upward trend in hospitalization rates for burns in children in the state (Spearman=0.806; p-value=0.005), despite the temporal trend of stability observed in all macro-regions (p-value>0.05). The highest mean hospitalization rate for burns between the years studied was found in Greater Florianópolis (mean 23.22 hospitalizations/100,000 inhabitants), while the lowest was obtained in the Grande Oeste macro-region (mean 8.12 hospitalizations/100,000 inhabitants).

| Year | South | Plan. Norte and Nordeste | Meio Oeste and Serra Cat. | Grande Oeste | Grande Florianópolis | Foz do Rio Itajaí | Vale do Itajaí | SC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 13.28 | 23.05 | 14.45 | 8.59 | 16.80 | 8.20 | 15.63 | 28.01 |

| 2013 | 12.90 | 25.09 | 13.62 | 6.09 | 21.51 | 10.04 | 10.75 | 30.69 |

| 2014 | 5.43 | 17.39 | 8.15 | 14.67 | 33.42 | 10.05 | 10.87 | 40.65 |

| 2015 | 9.78 | 19.55 | 8.10 | 13.97 | 26.82 | 8.38 | 13.41 | 39.69 |

| 2016 | 10.00 | 25.48 | 6.43 | 9.05 | 23.10 | 10.95 | 15.00 | 46.70 |

| 2017 | 9.38 | 11.54 | 8.17 | 6.73 | 35.58 | 12.26 | 16.35 | 46.36 |

| 2018 | 11.37 | 23.12 | 10.40 | 5.78 | 24.86 | 11.18 | 13.29 | 57.97 |

| 2019 | 18.76 | 23.80 | 7.32 | 7.09 | 27.00 | 5.95 | 10.07 | 48.90 |

| 2020 | 6.94 | 22.88 | 10.28 | 9.25 | 23.14 | 17.48 | 10.03 | 43.60 |

| 2021 | 13.76 | 18.34 | 8.73 | 7.64 | 25.55 | 12.45 | 13.54 | 51.43 |

| Mean Rate | 9.78 | 19.19 | 8.69 | 8.12 | 23.22 | 9.45 | 11.54 | 38.26 |

| Spearman | 0.139 | -0.152 | -0.248 | -0.152 | 0.333 | 0.600 | -0.261 | 0.806 |

| Beta | 0.161 | -0.123 | -0.487 | -0.303 | 0.216 | 0.470 | -0.210 | 0.800 |

| p-value | 0.656 | 0.735 | 0.153 | 0.394 | 0.549 | 0.171 | 0.560 | 0.005 |

Table 3 presents hospitalization rates according to the body length burned, the mean length of stay, the proportion of hospitalizations that required intensive care support (ICU), and the hospital mortality rate in the period studied. Concerning the extent of the burn, there was a significant tendency towards a reduction in hospitalization rates for major burns (Spearman= -0.879; p-value=0.002), and minor burns (Spearman = -0.855; p-value=0.021). The temporal trend in hospitalization rates for burn victims indicated a trend of stability (Spearman= -0.636; p-value=0.060).

| Year | Burn Extent (Rate) | Length of stay (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small burn | Medium burn | Large burn | 0-3 days | 4-7 days | 8-14 days | 15 or more | % ICU | |

| 2012 | 7.81 | 40.23 | 17.58 | 32,422 | 32,031 | 25,391 | 10,156 | 8.59 |

| 2013 | 3.23 | 34.77 | 13.98 | 50,538 | 21,864 | 21,147 | 6,452 | 6.81 |

| 2014 | 3.80 | 29.35 | 16.85 | 57,337 | 22,011 | 14,402 | 6,250 | 3.26 |

| 2015 | 6.15 | 18.99 | 23.18 | 54,469 | 22,626 | 17,039 | 5,866 | 0.56 |

| 2016 | 3.10 | 26.67 | 12.38 | 62,143 | 19,524 | 13,810 | 4,524 | 4.76 |

| 2017 | 2.64 | 31.97 | 6.25 | 61,538 | 18,750 | 14,423 | 5,288 | 0.72 |

| 2018 | 1.73 | 24.47 | 4.43 | 65,896 | 16,763 | 13,680 | 3,661 | 5.59 |

| 2019 | 2.75 | 26.09 | 4.12 | 56,979 | 26,545 | 10,984 | 5,492 | 6.41 |

| 2020 | 2.57 | 24.16 | 4.63 | 61,183 | 22,108 | 13,625 | 3,085 | 5.91 |

| 2021 | 2.18 | 25.33 | 2.62 | 62,009 | 20,087 | 13,974 | 3,930 | 3.71 |

| Average | 3.38 | 25.67 | 10.34 | 50,250 | 20,222 | 14,450 | 5,077 | 4.26 |

| Spearman | -0.855 | -0.636 | -0.879 | 0.636 | -0.285 | -0.794 | -0.867 | -0.248 |

| Beta | -0.713 | -0.612 | -0.838 | 0.717 | -0.430 | -0.778 | -0.819 | -0.166 |

| p-value | 0.021 | 0.060 | 0.002 | 0.020 | 0.215 | 0.008 | 0.004 | 0.648 |

Regarding length of stay, there was a significant trend towards growth in short-stay hospitalizations (0-3 days) (Spearman= -0.794; p-value=0.008), towards stability in medium-stay hospitalizations (Spearman= -0.285; p-value 0.215), and a reduction in long-term stays (8 days or more) (Spearman between -0.794 and -0.867; p-value<0.008). The mean proportion of hospitalizations that required ICU was just 4.26%, with a trend of stability over the period.

Table 4 presents hospitalization rates for burns according to the affected body region. The affected regions were grouped according to Chapter XIX – ICD 10, being T20-T21 (head, neck, and trunk), T22-T23 (shoulder, upper limbs, wrist, and hand), T24-T25 (hip, lower limbs, ankle, and foot), T26-T28 (eye, respiratory tract, and internal organs) and T29 (multiple regions). There was a temporal trend towards stability in hospitalization rates in all locations surveyed (p-value > 0.05).

| Year | Head, Neck, and Trunk | Shoulder, Upper limbs, Fist and Hand | Hip, Lower Limbs, Ankle. and foot | Eye, Resp Tract, and internal bodies | Multiple regions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 32.81 | 13.67 | 9.77 | 3.91 | 16.41 |

| 2013 | 35.84 | 17.56 | 7.89 | 3.23 | 20.07 |

| 2014 | 46.47 | 17.12 | 7.07 | 3.53 | 13.86 |

| 2015 | 49.72 | 15.36 | 7.26 | 1.96 | 9.22 |

| 2016 | 32.62 | 12.14 | 11.90 | 4.29 | 29.29 |

| 2017 | 37.74 | 20.91 | 7.69 | 2.64 | 17.07 |

| 2018 | 24.28 | 13.49 | 4.62 | 2.50 | 37.76 |

| 2019 | 32.72 | 12.81 | 4.81 | 2.52 | 24.71 |

| 2020 | 30.33 | 17.74 | 10.28 | 4.88 | 11.57 |

| 2021 | 29.48 | 15.72 | 10.04 | 4.15 | 20.52 |

| Tx Média | 32.25 | 14.08 | 7.13 | 2.95 | 18.00 |

| Spearman | -0.648 | 0.018 | 0.067 | 0.164 | 0.285 |

| Beta | -0.494 | 0.009 | -0.032 | 0.169 | 0.224 |

| p-value | 0.146 | 0.981 | 0.930 | 0.641 | 0.535 |

DISCUSSION

The study analyzed the temporal trend, regional distribution, and profile of morbidity and mortality from burns in children aged 0 to 9 years, in Santa Catarina, from 2012 to 2021, based on data available in the Hospital Information System.

The results obtained demonstrated a growing trend in hospitalization rates for burns in children in the State in the period analyzed. This finding is in line with the results of the study by Pereima et al.13, which indicated an increase in the number of hospitalizations for burns in children aged 0 to 14 years, in both sexes, in Santa Catarina, from 2008 to 2015. However, Brazil showed a decrease in the number of hospitalizations in the same period.

It is worth highlighting that the divergence between the increase in the number of hospitalizations in Santa Catarina and the decrease in hospitalizations in the country may be related to the colder climate, characteristic of the Southern Region of Brazil. In winter, the preparation of hot food is more frequent, and there is greater use of kitchens by families due to the temperature in this environment, generating a greater risk of scalds14.

Regarding the epidemiological profile of children affected by burns, a study by Rigon et al.15, which analyzed the profile of children victims of burns in a children’s hospital located in the Planalto Serrano region in Santa Catarina, found similar results to the present study, with greater prevalence in males (60.3%) and in children under 5 years of age (72%).

These data are similar to studies carried out in other states in Brazil, such as that by Barros et al.16, which analyzed data from children victims of burns treated at a tertiary hospital in Campo Grande/MS, in 2015, and demonstrated a higher prevalence in male (59%) and aged 1 to 4 years (42%).

The predominance of cases involving males may be related to cultural and behavioral factors. Boys tend to have more freedom and practice activities that leave them more exposed to risk, while girls are under greater surveillance and are usually more cautious17,18.

Regarding age group, the higher prevalence of burn cases in children in the first years of life is related to the characteristics of the developmental stage in which they find themselves. As a consequence of their immaturity, curiosity, and lack of motor coordination, they are often exposed to dangerous situations. Other factors that increase the risk of accidents are easy access to the kitchen and inadequate supervision by those responsible7,17.

The period evaluated in the present study allowed a comparison of hospitalization rates due to burns before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, demonstrating a growing trend in the hospitalization rate in the state. Studies carried out in several countries, such as France, Indonesia, the United States, Poland, and Israel, found an increase in the number of pediatric visits for burns during the lockdown, compared to the period before the pandemic19,20,21,22,23.

The increase in the number of hospitalizations for childhood burns in 2020 may be related to changes in lifestyle during the pandemic, as, with the implementation of social isolation measures, face-to-face classes were suspended and children underwent more hours at home. At the same time, many parents began to work remotely. Because they need to divide their attention between their children and work, many adults may not have been able to adequately supervise their children, which increases the risk of accidents20,21,22.

Regarding hospitalization rates in the state’s macro-regions, we noticed that the region with the highest mean rate was Greater Florianópolis. This region alternated, with the macro-region of Planalto Norte and Nordeste, as having the highest hospitalization rates in the state.

What may have contributed to these regions having large number of hospitalizations is that the two largest reference centers for burns in the state are located in both: in Greater Florianópolis, in the capital, there is the Hospital Infantil Joana de Gusmão, and in the macro-region of Planalto Norte and Nordeste, in Joinville, the São José Municipal Hospital and the Dr. Jeser Amarante Faria Children’s Hospital are located. Therefore, many cases from neighboring regions are referred to the nearest reference centers without registering their place of residence. The Article of Faith24 carried out in Santa Catarina, found similar results, even studying different age groups and periods.

According to the degree and extent of the burned body surface, the Ministry of Health classifies injuries as small, medium, and large burned25. Cases classified as medium burns were the most prevalent group in the period studied in Santa Catarina, which is in line with the findings of Barros et al.16, who found, in a hospital in Campo Grande/MS, a higher proportion of minor burns.

Regarding the days of hospitalization of the studied patients, there was a prevalence (50.2%) of short-term hospitalizations (0 to 3 days), while Fernandes et al.26 recorded a mean of 5.87 days. Other studies, such as that by Rigon et al.15, found an even longer hospital stay (11 days). This difference may be related to the severity profile of the injuries of the patients studied in each study, which strongly determines the length of stay, as it depends on the complexity and rate of Burned Body Surface.

Regarding the need for ICU admission, the average rate found in Santa Catarina was 4.2%, similar to the 5% observed by Rigon et al.15. In the same context, the average death rate in the present research was 0.3/100,000 inhabitants, while that in the study just mentioned was 1.2%. These small death rates corroborate the perception that there was a trend towards a general reduction in the mortality of burn victims in more recent studies when compared to previous periods, explained both by the reduction in the prevalence of more severe burns and by the reduction in burns associated with other complications, like smoke inhalation.

The highest mortality is strongly associated with burns with a larger body surface area (>60%)27. When evaluating the areas most affected by burns in children, recent studies describe greater involvement of the trunk, head, and upper limbs, which corroborates the findings of this research28. Despite the temporal trend of decreasing involvement of the previously mentioned areas of the body, these remain the main affected regions, probably explained by the difference in level between the agent causing the burn and the child’s position, almost always in a lower plane15,29.

Children, especially those of preschool age, tend to pull objects with heated contents close to them, such as pans on top of the stove, in addition to being more curious about the external environment, which can unintentionally cause episodes of burns, which predominate in the upper regions of the body29,30.

It is worth highlighting that the present study has some limitations. As it is based on data available in SIH-SUS from DATASUS, the rates found are dependent on the correct completion of patient information, therefore, they are subject to information bias. Furthermore, the design of this study does not allow determining a causal relationship between risk factors and morbidity and mortality from burns.

However, the findings identified the population that deserves more attention, indicated regions with a possible lack of medical and hospital equipment for adequate care for accidents involving burns in childhood, and reinforced the need for more effective prevention actions, such as virtual campaigns and in schools, to the guidance of children and their caregivers. Analysis of the information presented can also contribute to preparing health professionals for the most frequent conditions and guiding public investments to qualify the Unified Health System for this very relevant occurrence.

CONCLUSION

In Santa Catarina, there was a growing trend in hospitalization rates for burns in children aged 0 to 9 years, in both sexes, in the period from 2012 to 2021. A higher prevalence of hospitalizations for burns was found in males, in the age group of 0 to 4 years, and the Greater Florianópolis region. The group classified as medium burn was the most prevalent, while short-term hospitalizations (0 to 3 days) were the most frequent.

REFERENCES

1. Meschial WC, Sales CCF, Oliveira MLF. Fatores de risco e medidas de prevenção das queimaduras infantis: revisão integrativa da literatura. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2016;15(4):267-73.

2. Viana F P, Resende SM, Tolêdo MC, Silva RC. Aspectos epidemiológicos das crianças com queimaduras internadas no Pronto Socorro para queimaduras de Goiânia - Goiás. Rev Eletr Enferm. 2009;11(4):779-84.

3. Smolle C, Cambiaso-Daniel J, Forbes AA, Wurzer P, Hundeshagen G, Branski LK, et al. Recent trends in burn epidemiology worldwide: A systematic review. Burns. 2017;43(2):249-57.

4. Souza TG, Souza KM. Série temporal das internações hospitalares por queimaduras em pacientes pediátricos na Região Sul do Brasil no período de 2016 a 2020. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2022;37(4):438-44.

5. Oliveira C P, Sousa CJ, Gouveia SML, Carvalho V F. Controle da dor em crianças vítimas de queimaduras. Rev Saúde. 2013;7(3/4):56-64.

6. Gurgel AKC, Monteiro AI. Prevenção de acidentes domésticos infantis: susceptibilidade percebida pelas cuidadoras. J Res Fundam Care Online. 2016;8(4):5126-35.

7. Barcellos LG, Silva APP, Piva J P, Rech L, Brondani TG. Características e evolução de pacientes queimados admitidos em unidade de terapia intensiva pediátrica. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva. 2018;30(3):333-7.

8. Chang SSM, Freemantle J, Drummer OH. Fire/flames mortality in Australian children 1968-2016, trends and prevention. Burns. 2022;48(5):1253-60.

9. Andriadze M, Chikhladze N, Kereselidze M. General epidemiological characteristics of burn related injuries. J Exp Clin Med Georgia. 2022;63-8.

10. Coutinho JGV, Anami V, Alves TO, Rossatto PA, Martins JIS, Sanches LN, et al. Estudo de incidência de sepse e fatores prognósticos em pacientes queimados. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2015;14(3):193-7.

11. Romanowski KS, Palmieri TL. Pediatric burn resuscitation: past, present, and future. Burns Trauma. 2017;5:26.

12. World Health Organization (WHO). [Internet]. Burns. Geneva: WHO; 2018 [acesso 2022 Jun]. Disponível em: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns

13. Pereima MJL, Vendramin RR, Cicogna JR, Feijó R. Internações hospitalares por queimaduras em pacientes pediátricos no Brasil: tendência temporal de 2008 a 2015. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2019;18(2):113-9.

14. Moraes PS, Ferrari RAP, Sant’Anna FL, Raniero JTMW, Lima LS, SantosTFM. et al. Perfil das internações de crianças em um centro de tratamento para queimados. Rev Eletr Enf. 2014;16(3):598-603. http://dx.doi.org/10.5216/ree.v16i3.21968

15. Rigon A P, Gomes KK, Posser T, Franco JL, Knihs PR, Souza PA. Perfil epidemiológico das crianças vítimas de queimaduras em um hospital infantil da Serra Catarinense. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2019;18(2):107-12.

16. Barros LAF, Silva SBM, Maruyama ABA, Gomas MD, Muller KTC, Amaral MAO. Estudo epidemiológico de queimaduras em crianças atendidas em hospital terciário na cidade de Campo Grande/MS. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2019;18(2):71-7.

17. Martins CBG, Andrade SM. Queimaduras em crianças e adolescentes: análise da morbidade hospitalar e mortalidade. Acta Paul Enferm. 2007;20(4):464-9.

18. Dassie LTD, Alves EONM. Centro de tratamento de queimados: perfil epidemiológico de crianças internadas em um hospital escola. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2011;10(1):10-4.

19. Hennocq Q, Adjed C, Chappuy H, Orliaguet G, Monteil C, Kebir CE, et al. Injuries and child abuse increase during the pandemic over 12942 emergency admissions. Injury. 2022;53(10):3293-6.

20. Wihastyoko HYL, Arviansyah, Sidarta E P. The epidemiology of burn injury in children during COVID-19 and correlation with work from home (WFH) policy. Int J Public Health Sci. 2021;10(4):744-50.

21. Amin D, Manhan AJ, Mittal R, Abramowicz S. Pediatric head and neck burns increased during early COVID-19 pandemic. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2022;134(5):528-32.

22. Kawalec AM. The changes in the number of patients admissions due to burns in Pediatric Trauma Centre in Wroclaw (Poland) in March 2020. Burns. 2020;46(7):1713-4.

23. Yaacobi SD, Ad-El D, Kalish E, Yaacobi E, Olshinka A. Management Strategies for Pediatric Burns During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Burn Care Res. 2021;42(2):141-3.

24. Fé JH. Tendência Temporal da Morbimortalidade por queimaduras no estado de Santa Catarina [Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso]. Tubarão: Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina; 2020. Disponível em:_https://repositorio.animaeducacao.com.br/handle/ANIMA/16389

25. Luz SSA, Rodrigues JE. Perfis epidemiológicos e clínicos dos pacientes atendidos no centro de tratamento de queimados em Alagoas. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2014;13(4):245-50.

26. Fernandes FMFA, Torquato IMB, Dantas MSA, Pontes Júnior FAC, Ferreira JA, Collet N. Queimaduras em crianças e adolescentes: caracterização clínica e epidemiológica. Rev Gaúcha Enferm. 2012;33(4):133-41.

27. Shah AR, Liao L F. Pediatric burn care: unique considerations in management. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44(3):603-10.

28. Takino MA, Valenciano PJ, Itakussu EY, Kakitsuka EE, Hoshimo AA, Trelha CS, et al. Perfil epidemiológico de crianças e adolescentes vítimas de queimaduras admitidos em centro de tratamento de queimados. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2016;15(2):74-9.

29. Daga H, Morais IH, Prestes MA. Perfil dos acidentes por queimaduras em crianças atendidas no Hospital Universitário Evangélico de Curitiba. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2015;14(4):268-72.

30. Santana ME, Souza MWO, Santos FC. Perfil clínico e epidemiológico de crianças com queimaduras em um hospital de referência. Rev Enferm UFPI. 2018;7(2):23-7.

1. Universidade do Sul de Santa Catarina, Curso de

Medicina, Palhoça, Santa Catarina, Brazil

Corresponding author: Beatriz Rodrigues de Oliveira Carreirão Rua Duarte Schutel, 135, Centro, Florianópolis, Brazil. CEP 88015-640 E-mail: beatriz.carreirao@gmail.com

Article received: October 20, 2023.

Article accepted: April 30, 2024.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter