Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Epidemiology of burns in the state of Minas Gerais. What has changed in a decade?

Epidemiologia das queimaduras no estado de Minas Gerais. O que mudou em uma década?

ABSTRACT

Introduction: With a major impact on the population, burns require epidemiological analysis and constant planning for the prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of patients. This work aims to compare, after a decade, the indicators of the Burn Treatment Center at Hospital João XXIII, in Belo Horizonte, MG, covered in the article "Epidemiology of burns in the state of Minas Gerais", published in the Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica with data from 2010, to validate current and future strategies.

Method: Review of the medical records of patients suffering from burns, admitted to the aforementioned center in 2020.

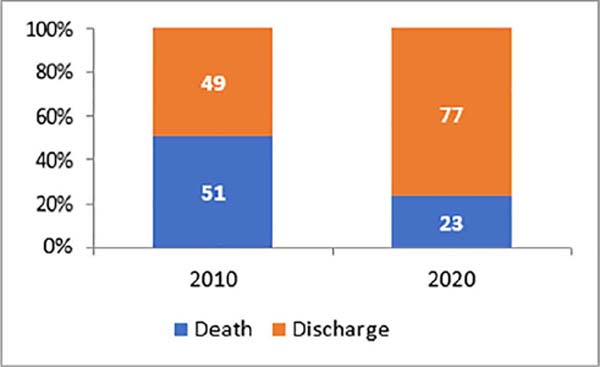

Results: 473 burn victims were hospitalized during the period, 87.5% were caused by an accident, 34.5% due to hot liquids, 23.7% by alcohol; 61.9% from the interior of the state of Minas Gerais; and 63.4% were male. The average age was 30 years, the average burned body surface area was 18.8% and the average length of stay was 25 days. 580 surgical debridement and 473 autologous skin grafts were performed. 7.4% of patients died, corresponding to 29.5% of those admitted to the adult ICU, with an average burned body surface area of 49.7%, and 10.5% of those admitted to the pediatric ICU. The biggest cause of death was sepsis, in 57.1% of cases. Mortality decreased from 16.3% to 7.4% in the period studied.

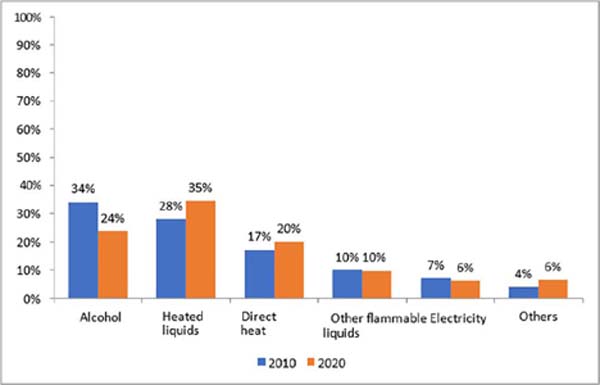

Conclusion: The profile of patients hospitalized for burns remained largely the same after 10 years. There was an increase in the number of visits to burn victims in the interior of the state and burns caused by hot liquids became more frequent than those caused by alcohol ''The search for compliance with treatment based on world literature resulted in reduction in mortality."

Keywords: Burns; Burn Units; Epidemiology; Mortality; Sepsis; Grafts

RESUMO

Introdução: De grande impacto na população, queimaduras exigem análise epidemiológica e planejamento constantes para prevenção, tratamento e reabilitação dos pacientes. Este trabalho objetiva comparar, após uma década, os indicadores do Centro de Tratamento de Queimados do Hospital João XXIII, em Belo Horizonte, MG, abordados no artigo "Epidemiologia das queimaduras no estado de Minas Gerais", publicado na Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica com dados de 2010, para validar as estratégias vigentes e as futuras.

Método: Revisão dos prontuários dos pacientes acometidos por queimadura, internados no referido centro em 2020.

Resultados: Foram internadas 473 vítimas de queimadura no período, 87,5% causadas por acidente, sendo 34,5% por líquidos quentes, 23,7% por álcool; 61,9% provenientes do interior do estado de Minas Gerais; 63,4% do sexo masculino. A idade média foi de 30 anos, a superfície corporal queimada média foi de 18,8% e o tempo médio de internação foi de 25 dias. Foram realizados 580 desbridamentos cirúrgicos e 473 enxertos cutâneos autólogos. Faleceram 7,4% dos pacientes, correspondentes a 29,5% dos internados no CTI adulto, com superfície corporal queimada média de 49,7%, e 10,5% dos internados no CTI pediátrico. A maior causa de óbitos foi devido à sepse, em 57,1% dos casos. A mortalidade diminuiu de 16,3% para 7,4% no período estudado.

Conclusão: O perfil do paciente internado por queimadura mantevese em grande parte o mesmo após 10 anos. Houve aumento do número de atendimentos a vítimas de queimadura do interior do estado e queimaduras provocadas por líquidos quentes passaram a ser mais frequentes que por álcool. ''A busca da conformidade com o tratamento baseado na literatura mundial resultou em diminuição da mortalidade."

Palavras-chave: Queimaduras; Unidades de queimados; Epidemiologia; Mortalidade; Sepse; Enxertos

INTRODUCTION

According to the Ministry of Health, there are currently forty-six high-complexity burn care reference centers in Brazil, five of them in Minas Gerais1. Due to the prevalence, morbidity, mortality, complexity, and excessive costs of treating burn victims, a permanent epidemiological study is necessary so that approach strategies can be proposed and validated, as well as the necessary resources for the prevention, therapy, and rehabilitation of patients.

The article “Epidemiology of burns in the state of Minas Gerais”, published in the Revista Brasileira de Cirurgia Plástica2, analyzes data from the year 2010 from the Burn Treatment Center (BTC) of Hospital João XXIII, the largest in Latin America specialized in the treatment of this disease.

OBJECTIVE

The objectives of this new study were to investigate epidemiological data from the year 2020 from a high-complexity BTC, installed at Hospital João XXIII, in Belo Horizonte-MG, and compare them to data from the same center presented a decade ago in the aforementioned article, to reorient planning.

METHOD

This is an observational, retrospective study, based on consultation of the medical records of patients admitted to the BTC of Hospital João XXIII, including wards and pediatric and adult intensive care centers, which compares data from 2020 to those from February 2009 to July 2010 of the aforementioned article. Variables from the previous study were included and new variables routinely recorded in the medical records were added. Patients treated in the emergency department, but not hospitalized, treated, and followed up on an outpatient basis, were excluded from this study. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Fundação Hospitalar do Estado de Minas Gerais, registered under number CAAE 07134818.7.0000.5119.

RESULTS

In 2020, 473 patients with burns were admitted to Hospital João XXIII, 63.4% male (300) and 36.6% female (173). The average age was 30 years old, and 21.6% (102) were aged between 0 and 4 years old.

40.6% (192) of patients were admitted to the adult burns ward, with an average age of 44 years, 31.7% (150) to the pediatric burns ward, with an average age of 4 years, 23.7% (112 ) in the Intensive Treatment Center (ICU) for adults, with an average age of 44 years, and 4.0% (19) in the pediatric ICU, with an average age of 5 years, with 38.1% (180) coming from the capital and 61.9% (293) from the interior of the state of Minas Gerais. The average length of stay for patients was 25 days, 17 days in the wards, 26 days in the adult ICU, and 30 days in the pediatric ICU.

The average burned body surface area (BBSA) of admitted patients was 18.8%, 19.2% among men and 18.1% among women. The average BBSA of those admitted to the wards was 12.6% of those admitted to the adult ICU 35% and of those admitted to the pediatric ICU 33%.

87.5% (414) of the patients suffered burns by accident and, by aggression, 6.1% (29). Burns caused by attempted self-extermination occurred in 6.4% (30) of patients, 70% (21) women and 30% (9) men.

Regarding the etiological agent of the burn, 34.5% (163) were caused by hot liquids, affecting 77.5% (79) of patients aged 0 to 4 years, 23.7% (112) by alcohol, 19.9% (94) by direct heat, 9.5% (45) by flammable liquids, except alcohol, 6.1% (29) by electricity, and 6.3% (30) by another agent. The average BBSA of burns caused by alcohol was 23.9%, and by hot liquids, 12.1%. Among victims of alcohol burns, 60.7% (68) were men.

In the pediatric ICU, 31.5% (6) of children were admitted with burns from direct flame, 26.3% (5) from scalds, 15.8% (3) from alcohol, 15.8% (3) from flammable materials, except alcohol, 5.3% (1) by caustic soda and 5.3% (1) by traumatic abrasion.

580 surgical debridement, 473 autologous grafts, 8 homologous grafts, and 24 flaps were performed. Regarding the outcome, 91.1% (431) of those admitted were discharged from the hospital and 1.5% (7) were transferred to private services. 7.4% (35) of patients died, corresponding to 29.5% (33) of those admitted to the adult ICU and 10.5% (2) of those admitted to the pediatric ICU.

Among the deaths, 94.3% (33) occurred in the adult ICU, 54.6% men and 45.4% women, with an average age of 43 years and an average BBSA of 49.7%. The average BBSA among men who died in this unit was 47.4%, and among women, 52.4%. The median length of stay until death was 9 days. Regarding the cause of burns that led to death in this unit, 63.6% (21) were by accident, 15.2% (5) by physical aggression, and 21.2% (7) by self-extermination. Among the thirty patients who attempted self-extermination, 23.3% (7) died, with an average age of 43 years, and an average BBSA of 69%. The burns that caused the most deaths were by alcohol, in 42.4% (14) of patients, followed by those caused by direct heat, in 33.3% (11) of cases, by flammable substances, except alcohol, in 15.2 % (5) of cases, and by a gaseous, chemical or electrical agent in 9.1% (3) of cases.

Among the deaths, 5.7% (2) occurred in the pediatric ICU, both from burns caused by accidents, one from airway burns, and the other from aspiration pneumonia.

The main cause of death was sepsis, corresponding to 57.1% (20) of cases, 28.6% (10) died due to dysfunction of multiple organs and systems, and 14.3% (5) died from other causes. The most prevalent germs that caused septicemia and death were Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecalis, and Enterobacter cloacae.

There were no deaths in the wards. Among the patients who died in 2020, only one was detected as positive for Covid-19. The cause of death was sepsis with a focus on skin wounds.

Comparing data from 2010 to 2020, it appears that the biggest burn victims continue to be men, young adults, with equivalent burned body surfaces, and hospitalized for more than three weeks (Table 1).

| 2010 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 62.5% | 63.4% |

| Women | 37.5% | 36.6% |

| Mean age | 29 | 30 |

| Mean BBSA | 20.8% | 18.8% |

| Mean BBSA in male patients | 20% | 19.2% |

| Mean BBSA in female patients | 22.3% | 18.1% |

| Mean length of stay (days) | 23.5 | 25 |

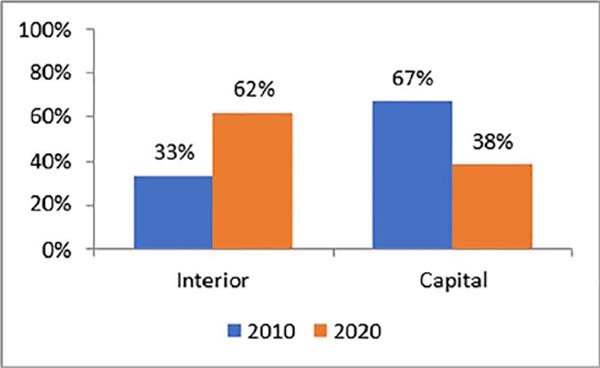

However, during this period there was a reversal in the origin of the patients. In 2010, the majority of hospitalized patients lived in the capital. In 2020, the majority lived in the interior of the state (Figure 1).

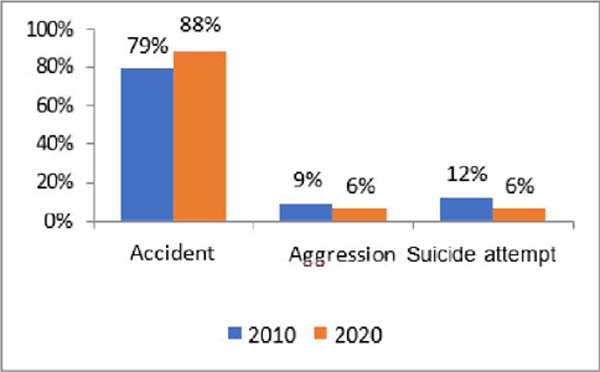

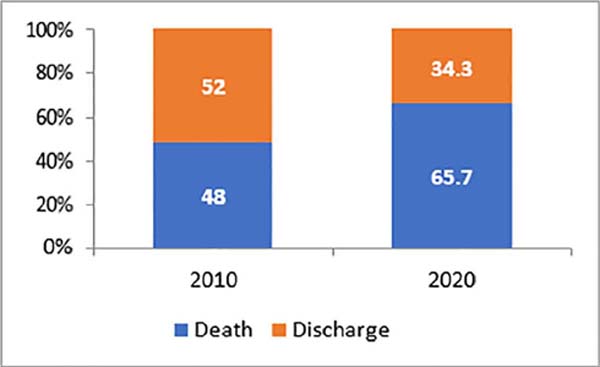

Burns caused by accidents were even more frequent and caused more deaths in 2020, unlike burns caused by attempted self-extermination (Figures 2, 3, 4).

Self-extermination attempts remained predominant among female patients in 2010 (66%) and 2020 (70%), and caused 39% of deaths in 2010, and 20% in 2020. Among deaths due to self-extermination in 2010 were of younger patients, with less BBSA involvement (Table 2). These data are similar to those published in a specific study of the same BTC3.

In 2010, alcohol was the most prevalent etiological agent. In 2020 it remained relevant but was surpassed by hot liquids (Figure 5), mainly up to the age of 4 years in both periods. From 5 years of age onwards, the main etiological agent was alcohol in both studies. During this period, it remained the etiological agent that caused the most severe burns, with a mean BBSA of 28% in 2010 and 23.9% in 2020, responsible for 52.7% of patients who died in 2010, and 40% in 2020.

In 2010, the author identified a mortality of 16.3%, with a downward trend, and in 2020 mortality actually decreased to 7.4%. The average number of surgical procedures per patient coincided in both periods (2.28 versus 2.24). There were 0.85 autograft procedures per patient in 2010 and 1.00 per patient in 2020.

DISCUSSION

Comparing different moments in the same treatment center allows you to evaluate indicators that validate current planning or alert you to the need for corrections. Comparing data from different centers is a challenging task, since, although burn treatment is well established in the world literature, there are variables that are difficult to isolate and control, such as the pressure that demand imposes with limited public service resources, transfer delay of patients from non-specialized centers, and the efficiency of pre-hospital care, which generates admissions of patients with a very unfavorable prognosis, whose most likely outcome would have been death at the scene of the trauma. There are dramatic cases of patients with BBSA close to 100%, who arrive at the emergency room oriented and talking, but whose death outcome is, in current practice, irreversible.

Globally, mortality from burns is around 5%4. However, depending on the scope of the publication, very different data are found in the world literature, such as a mortality rate of 37.75% in a study in Iran5, 36.12% in a study that excluded children in Pakistan4, 23.4% in Cameroon6, 5.3% in the United States4, and 4.3% in Spain7, in a study in which only 9.7% were severely burned and whose average BBSA was only 8.3%.

The present work aimed to compare the evolution of the same treatment center when faced with literature data from a decade ago. The publication of very favorable data is always an inspiration to achieve better results. Regarding the comparison of very specific data in different periods, it is not possible to conclude about apparently better results in studies not aimed at this specific purpose, as the availability of resources may depend on non-isolated variables, such as the complexity of cases admitted at the same time.

Between the periods studied, a greater number of critically ill patients were referred for treatment in the state capital, with centers in the interior responsible for small and medium-sized local burns. At the BTC of Hospital João XXIII, we sought to intensify the performance of early debridement and skin grafts and at the same surgical time, as recommended in the literature8, to reduce the mortality rate. The use of homologous grafts was not greater due to limited availability in the country’s skin banks. It was also committed to intensifying the effort to decide to provide skin coverage to wounds with borderline epithelialization times so that they would not heal spontaneously and generate retraction sequelae.

The increase in deaths due to accidental burns between the periods evaluated demonstrates the need to intensify prevention actions. The role of alcohol in the most unfavorable outcomes from the age of five continues, and the need for special attention directed towards regulating the sale of this substance and preventive campaigns to raise awareness among the population.

There are several ongoing actions aimed at improving indicators. The request to acquire technology for micrografting from Meek9 aims to seek an alternative for more serious cases, in which there are not enough skin donor regions for autologous grafting. Currently, mesh expansion is used in the aforementioned BTC, in which the skin recruited for grafting is guided along a perforator roller, which produces transfixing linear cuts across its entire surface. When pulled, the cuts become holes, with a consequent increase in the skin area, doubling, tripling, or quadrupling it, depending on the surgeon’s decision. The Meek technique produces orthogonal cuts in the skin recruited for grafting. When transferred over a pre-accordion dressing, which allows traction in both directions, it produces a matrix of small square grafts, expanding the recruited skin by up to nine times, allowing coverage of larger areas.

The request for the acquisition of extracellular matrices aims to facilitate the simplification of selected procedures in regions with exposure of noble structures without the availability of local flaps, to allow treatment with skin grafting and shorten hospitalization time, directly associated with mortality. Other actions are the creation of a state service for regulating transfers to the BTC of high complexity, encouragement of the creation of new treatment centers for major burns in the state, proposal to create a distance training program for non-specialists, raising public awareness of carrying out a permanent burn prevention campaign and including accident prevention subjects in the school curriculum.

CONCLUSION

The profile of the burn victim treated at BTC Professor Ivo Pitanguy was largely maintained over 10 years. However, the number of patients from the interior of the state increased, and hot liquids overtook alcohol as the most prevalent burn-provoking agent. Experience and the search for compliance with treatment based on world literature resulted in more favorable indicators, with the reduction in mortality being the most significant.

REFERENCES

1. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Habilitações. [acesso 2024 fev 10]. Disponível em: http://cnes2.datasus.gov.br/Mod_Ind_Habilitacoes_Listar.asp

2. Leão CEG, Andrade ES, Fabrini DS, Oliveira RA, Machado GLB, Gontijo LC. Epidemiologia das queimaduras no estado de Minas Gerais. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2011;26(4):573-7.

3. Oliveira RA, Andrade ES, Leão CEG. Epidemiologia das tentativas de autoextermínio por queimaduras no estado de Minas Gerais. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2012;11(3):125-7.

4. Ibran E, Mirza FH, Memon AA, Farooq MZ, Hassan M. Mortality associated with burn injury - a cross sectional study from Karachi, Pakistan. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:545.

5. Ghahghai M, Ghorbani SS, Hoseininejad S, Sheikhi A, Farhadi M, Rahbar R. Factors responsible for mortality among burns patients in Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2023;29(8):650-6.

6. Forbinake NA, Ohandza CS, Fai KN, Agbor VN, Asonglefac BK, Aroke D, et al. Mortality analysis of burns in a developing country: a CAMEROONIAN experience. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1269.

7. Abarca L, Guilabert P, Martin N, Usúa G, Barret J P, Colomina MJ. Epidemiology and mortality in patients hospitalized for burns in Catalonia, Spain. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):14364.

8. Janzekovic Z. A new concept in the early excision and immediate grafting for burns. J Trauma. 1970;10(12):1103-8.

9. Kreis RW, Mackie D P, Hermans R P, Vloemans AR. Expansion techniques for skin grafts: comparison between mesh and Meek island (sandwich-) grafts. Burns. 1994;20(Suppl 1):S39-42.

1. Hospital João XXIII, Centro de Tratamento de

Queimados - Belo Horizonte - Minas Gerais - Brazil

Corresponding author: Rodrigo Pimenta Sizenando Av. das Constelações, 725, P3/302, Nova Lima, MG, Brazil CEP: 34008-050 E-mail: rodrigosizenando@hotmail.com

Article received: October 04, 2023.

Article accepted: April 30, 2024.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter