Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Factors predicting burn unit length-of-stay

Fatores preditivos da permanência em uma Unidade de Queimados

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Burn patients' mortality rate has decreased significantly, making it important to evaluate other outcomes, such as length-of-stay, which increases physical and psychological morbidity, risk of nosocomial infection, and financial costs. The objective of this study is to analyze the relevance of several factors in the Burn Unit length-of-stay.

Material and Methods: 711 patients were included in this study, admitted between 2011 and 2020 to the Burn Unit at São José Hospital, Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Central, Lisbon, Portugal. Collected data was analyzed using PSPP for Windows.

Results: Patients included in the study were predominantly males, with a mean age of 54 years. The mean length of stay was 29 days. The factors that prolonged in-hospital stay were those related to the severity of the burn, the number of surgeries and the time elapsed until the first one, altered laboratory values in both hematologic and chemistry profile during the hospitalization, and the presence and number of documented infections.

Conclusion: There are potentially modifiable factors that influence length-of-stay. Our study allows us to conclude that the time elapsed until the first surgical intervention and the presence and number of documented infections significantly prolong this outcome, and emphasis should be given to the implementation of measures that favor early surgical intervention and strict infection control.

Keywords: Burn units; Length of hospital stay; Hospital mortality; Graft survival; Plastic surgery procedures

RESUMO

Introdução: A taxa de mortalidade em pacientes queimados diminuiu significativamente, tornando importante avaliar outros desfechos, como o tempo de internação, que aumenta a morbidade física e psicológica, o risco de infecção hospitalar e os custos financeiros. O objetivo deste estudo é analisar a relevância de vários fatores no tempo de internação na Unidade de Queimados.

Método: Foram incluídos neste estudo 711 pacientes admitidos entre 2011 e 2020 na Unidade de Queimados do Hospital de São José, Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Central, Lisboa, Portugal. Os dados coletados foram analisados utilizando o PSPP para Windows.

Resultados: Os pacientes eram predominantemente do sexo masculino, com idade média de 54 anos. O tempo médio de permanência hospitalar foi de 29 dias. Os fatores que prolongaram a estadia hospitalar foram relacionados à gravidade da queimadura, ao número de cirurgias e ao tempo decorrido até a primeira cirurgia, valores laboratoriais alterados tanto no perfil hematológico quanto químico durante a hospitalização, e a presença e o número de infecções documentadas.

Conclusão: Existem fatores potencialmente modificáveis que influenciam o tempo de permanência hospitalar. Nosso estudo nos permite concluir que o tempo decorrido até a primeira intervenção cirúrgica e a presença e o número de infecções documentadas prolongam significativamente esse desfecho, e ênfase deve ser dada à implementação de medidas que favoreçam a intervenção cirúrgica precoce e o controle rigoroso de infecções.

Palavras-chave: Unidades de queimados; Tempo de internação; Mortalidade hospitalar; Sobrevivência de enxerto; Procedimentos de cirurgia plástica

INTRODUCTION

Due to a generalized improvement in healthcare, the last 30 years presented us with a significant reduction in the mortality rate of burn patients1,2. Several factors are responsible for this change such as a better understanding of the physiopathology of severe burns, the widespread development of critical care units, and new patient-tailored therapeutic strategies, namely, aggressive fluid resuscitation, rigorous infection control and early surgical intervention with thorough debridement and skin grafting to surpass the loss of assessment power of burn-related mortality.

Therefore, to evaluate the quality and efficiency of clinical care, it is important to assess other outcomes such as length of stay3 whose increase is irrefutably associated with adverse consequences. A longer stay in a burn unit or intensive care unit has been associated with a higher physical (and psychological morbidity, a delayed return to work, decreased productivity, lower health-related quality of life, and a higher and a higher incidence of psychopathological symptoms4,5.

Burn patients are particularly susceptible to infection. A prolonged length of stay increases the risk of nosocomial infection, which in turn increases the length of stay in a burn unit by an average of 18 days. Furthermore, an increased length of stay has been proven to be directly related to the development of antibiotic resistance. The most common infections in this context are caused by aggressive microorganisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Infection by this microorganism is associated with increased all-cause mortality and morbidity.

At last, an increased length of stay is associated with an increased social and economic cost. In Portugal, the average cost of a stay in a Burns Unit in 2013 was 8032 euros6,7. The following factors have been associated with a more prolonged stay: age8,9, male sex9, percentage of burnt surface area8,9, depth of burn10, presence of airway injury9, comorbidities or associated traumatic injury11, need for a surgical procedure8,10 and the presence of infection or sepsis10.

In this retrospective study, the authors aim to establish what factors are relevant to the length of stay in a Burn Unit in Portugal, to identify specific measures and interventions that might allow the reduction of hospitalization time and therefore the morbidity and mortality associated with it.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this retrospective study, all patients admitted to the Burnt Patient Special Care Unit in the Hospital Universitário Lisboa Central between the 1st of January 2011 and the 31st of December 2020 were assessed. A total of 745 patients was collected. Patients were excluded from the study due to early discharge to another unit for medical or logistic reasons10; discharge against doctor orders3 or admission with a non-burn condition (toxic epidermal necrolysis)2.

The data from the resulting 711 patients was collected regarding age, sex, previous medical conditions, date of admission and discharge of the burn unit, mechanism of burn, agent of burn, area of burn, depth of burn, associated traumatic injuries, need for ventilation, need for fasciotomy or escharotomy, airway injury, need for and timing to surgical intervention, infection and site of infection, laboratory parameters and clinical outcome. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows. A p-value <0,05 was considered significant. (Table 1)

| n=711 | |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 398 (56%) |

| Female | 313 (44%) |

| Age (average, years) | 54 |

| Minimal age | 17 |

| Maximum age | 95 |

| Age group | |

| Less than 20 years | 21 (3%) |

| 21-40 years | 202 (28%) |

| 41-60 years | 238 (34%) |

| 61-80 years | 159 (22%) |

| 81-100 years | 91 (13%) |

| Length of stay (average, days) | 29 |

| Minimal stay (days) | 1 |

| Maximum stay (days) | 254 |

| Length of stay | |

| Less than 7 days | 80 (11%) |

| Less than 30 days | 468 (66%) |

| Less than 60 days | 644 (91%) |

| Less than 120 days | 702 (99%) |

| More than 120 days | 9 (1%) |

| Days in Burn Unit > Percentage of burn | |

| Yes | 578 (81%) |

| No | 133 (19%) |

| Medical comorbidities | |

| Yes | 353 (50%) |

| No | 358 (50%) |

| Burn agent | |

| Thermal | 623 (88%) |

| Electrical | 70 (10%) |

| Chemical | 18 (2%) |

| Burn agent | |

| Fire | 359 (51%) |

| Liquid | 227 (32%) |

| Electric | 70 (10%) |

| Contact | 37 (5%) |

| Chemical | 18 (2%) |

| Burn surface (average, percentage) | 14 |

| Minimal | 0 |

| Maximum | 91 |

| Burn surface | |

| Less than 10% | 396 (56%) |

| 11-20% | 186 (26%) |

| 21-30% | 59 (8%) |

| 31-40% | 29 (4%) |

| 41-50% | 16 (2%) |

| 51-60% | 8 (1%) |

| 61-70% | 4 (1%) |

| 71-80% | 5 (1%) |

| 81-90% | 7 (1%) |

| More than 90% | 1 (0%) |

| Burn surface | |

| Less than 10% | 396 (56%) |

| Less than 20% | 582 (82%) |

| Less than 30% | 641 (90%) |

| Less than 40% | 670 (94%) |

| Less than 50% | 686 (97%) |

| Less than 60% | 694 (98%) |

| Less than 70% | 698 (98%) |

| Less than 80% | 703 (99%) |

| Less than 90% | 710 (100%) |

| More than 90% | 1 (0%) |

| Third-degree burns | |

| Yes | 379 (53%) |

| No | 332 (47%) |

| Mechanical ventilation | |

| Yes | 208 (29%) |

| No | 503 (71%) |

| Duration of Mechanical ventilation (average, days) – n=208 | 12 |

| Minimal | 1 |

| Maximum | 67 |

| Mechanical ventilation > 12 Days – n=208 | |

| Yes | 58 (28%) |

| No | 150 (72%) |

| Inhalatory injury | |

| Yes | 112 (16%) |

| No | 599 (84%) |

| Associated trauma | |

| Yes | 49 (7%) |

| No | 662 (93%) |

| Escharotomies | |

| Yes | 118 (17%) |

| No | 593 (83%) |

| Surgical Intervention | |

| Yes | 505 (71%) |

| No | 206 (29%) |

| Number of Surgical Interventions (average) – n=505 | 2 |

| Minimum | 1 |

| Maximum | 17 |

| Timing of the 1st Surgical Intervention (average, days) – n=505 | 9 |

| Minimum | 1 |

| Maximum | 36 |

| Timing of the 1st Surgical Intervention (days) – n=505 | |

| First 5 Days | 131 (26%) |

| First 10 Days | 327 (65%) |

| First 15 Days | 435 (86%) |

| First 20 Days | 479 (95%) |

| After 20 Days | 27 (5%) |

| Documented infection | |

| Yes | 328 (46%) |

| No | 383 (54%) |

| Nosocomial infection | |

| Yes | 261 (37%) |

| No | 450 (63%) |

| Number of Documented infections (average) – n=711 | 2 |

| Minimum | 0 |

| Maximum | 13 |

| Number of infections – n=328 | |

| 1-2 Infections | 231 (71%) |

| 3-4 Infections | 57 (17%) |

| 5-6 Infections | 23 (7%) |

| More than 6 infections | 17 (5%) |

| Mucocutaneous infection | |

| Yes | 151 (21%) |

| No | 560 (79%) |

| Respiratory infection | |

| Yes | 61 (9%) |

| No | 650 (91%) |

| Urinary tract infection | |

| Yes | 172 (24%) |

| No | 539 (76%) |

| Systemic infection | |

| Yes | 132 (19%) |

| No | 579 (81%) |

| Minimum hemoglobin (average, g/dl) | 11,9 |

| Anemia (Hb < 8 g/dl) | |

| Yes | 30 (4%) |

| No | 681 (96%) |

| Renal disease (Creatinina > 1,2 mg/dl) | |

| Yes | 89 (13%) |

| No | 622 (87%) |

| Minimum total protein value (average, g/l) | 50,7 |

| Hypoproteinemia (Total protein < 60g/l) | |

| Yes | 557 (78%) |

| No | 154 (22%) |

| Hipoalbuminemia (Albumina < 35g/l) | |

| Yes | 569 (80%) |

| No | 142 (20%) |

| ABSI (average) | 6 |

| Minimum | 2 |

| Maximum | 17 |

| Threat to Life | |

| Very Low (ABSI 2-3) | 56 (8%) |

| Moderate (ABSI 4-5) | 243 (34%) |

| Moderately Severe (ABSI 6-7) | 254 (36%) |

| Serious (ABSI 8-9) | 111 (16%) |

| Severe (ABSI 10-11) | 22 (3%) |

| Maximum (ABSI 12 or Superior) | 25 (3%) |

| Mortality > 50% ABSI (> 10) | |

| Yes | 47 (7%) |

| No | 664 (93%) |

| Baux Score (average) | 67 |

| Minimum | 21 |

| Maximum | 169 |

| Modified Baux Score (average) | 70 |

| Minimum | 23 |

| Maximum | 189 |

| Mortality > 50% Modified Baux Score (≥ 140) | |

| Yes | 14 (2%) |

| No | 697 (98%) |

| Death | |

| Yes | 43 (6%) |

| No | 668 (94%) |

RESULTS

Population Analysis:

After the application of the exclusion criteria, a total of 711 patients was included. There were 398 male patients (56%; Table 1). Age varied between 17 and 95, with an average of 54 years old. Duration of stay was, on average, 29 days (minimum of 1 day; maximum of 254 days). About half of the patients had a medical co-morbidity. Thermal burn was the most common mechanism (88%), being fire the most common causative agent (51%). The body surface area affected varied between 0 a 91% at admission, with an average of 14%, 53% of patients presented third-degree burns at admission, 7% presented associated trauma, 29% of patients needed mechanical ventilation, with an average duration of ventilation of 12 days, and 16% presented airway lesion under bronchoscopy, 17% of patients required escharotomy of fasciotomy at admission, 71% of patients underwent surgery, with an average of 2 procedures per patient. Surgery was performed between the 1st and the 36th day of admission, with an average time to surgery of 9 days.

At admission, every patient was submitted to an MRSA nasal swab, a perineal region swab, and a burn and sane skin swab. Additional cultures were collected if the clinical situation deemed it. One or more microbiological agents were cultured in 46% of patients, and in 37% of patients, it was of nosocomial origin. The average number of positive cultures was 2. The most frequent infection was in the urinary tract. In terms of laboratory anomalies, the most frequent alteration was hypoproteinemia (79%) and hypoalbuminemia (80%). The average ABSI score was 6. The average Modified Baux Score was 70. The average mortality rate was 6%.

Duration of Stay

Duration of stay in the Burn unit averaged 29 days. The minimum was 1 day and the maximum was 254 days. The following factors were associated with an increased length of stay: female sex (p-value 0,048); age (p-value 0,002); and presence of co-morbidities (p-value 0,015). (Table 2).

| Statistical Average | p value | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 27 | 0,048 T |

| Female | 31 | |

| Age | 0,002 S | |

| Age Group – years old | ||

| <20 | 16 | |

| 21-40 | 25 | 0,007 A |

| 41-60 | 30 | |

| 61-80 | 33 | |

| 81-100 | 31 | |

| Medical Comorbidities | ||

| Yes | 31 | 0,015 T |

| No | 27 | |

| Burn Mechanism | ||

| Thermal | 30 | 0,000 A |

| Electrical | 20 | |

| Chemical | 17 | |

| Thermal Burn | ||

| Yes | 30 | 0,000 T |

| No | 19 | |

| Electrical Burn | ||

| Yes | 20 | 0,001 T |

| No | 30 | |

| Chemical Burn | ||

| Yes | 17 | 0,048 T |

| No | 29 | |

| Fire Injury | ||

| Yes | 35 | 0,000 T |

| No | 23 | |

| Hot Líquid Injury | ||

| Yes | 24 | 0,000 T |

| No | 31 | |

| Contact Burn Injury | ||

| Yes | 23 | 0,167 T |

| No | 29 | |

| Burn Injury Agent | ||

| Fire | 35 | |

| Hot Liquid | 24 | |

| Electric | 20 | 0,000 A |

| Contact Burn | 23 | |

| Chemical | 17 | |

| Body Surface area | 0,000 S | |

| Body Surface area (%) | ||

| < 10% | 20 | |

| 11-20% | 32 | |

| 21-30% | 45 | |

| 31-40% | 48 | |

| 41-50% | 71 | 0,000 A |

| 51-60% | 94 | |

| 61-70% | 40 | |

| 71-80% | 32 | |

| 81-90% | 61 | |

| > 90% | 5 | |

| Body Surface area up to 10% | ||

| Yes | 20 | 0,000 T |

| No | 40 | |

| Body Surface area from 10 to 20% | ||

| Yes | 24 | 0,000 T |

| No | 52 | |

| Body Surface area from 20 to 30% | ||

| Yes | 26 | 0,000 T |

| No | 58 | |

| Body Surface area from 30 to 40% | ||

| Yes | 27 | 0,000 T |

| No | 64 | |

| Body Surface area from 50 to 60% | ||

| Yes | 28 | 0,000 T |

| No | 60 | |

| Body Surface area from 50 to 60% | ||

| Yes | 29 | 0,012 T |

| No | 44 | |

| Body Surface area from 60 to 70% | ||

| Yes | 29 | 0,018 T |

| No | 45 | |

| Body Surface area from 70 to 80% | ||

| Yes | 29 | 0,005 T |

| No | 54 | |

| Body Surface area from 80 to 90% | ||

| Yes | 29 | 0,344 T |

| No | 5 | |

| 3rd Degree Burn | ||

| Yes | 37 | 0,000 T |

| No | 20 | |

| Need for Mechanical Ventilation | ||

| Yes | 36 | 0,000 T |

| No | 26 | |

| Duration of Mechanical Ventilation – n=208 | 0,000 S | |

| Duration of Mechanical Ventilation > 12 days | ||

| Yes | 57 | 0,000 T |

| No | 28 | |

| Inhalatory Injury | ||

| Yes | 43 | 0,000 T |

| No | 26 | |

| Associated Trauma | ||

| Yes | 34 | 0,125 T |

| No | 29 | |

| Need for Escharotomy | ||

| Yes | 50 | 0,000 T |

| No | 25 | |

| Need for surgical intervention | ||

| Yes | 36 | 0,000 T |

| No | 13 | |

| Number of Surgical Interventions – n = 505 | 0,000 S | |

| Timing of 1st Surgical Intervention – n=505 | 0,000 S | |

| Timing of 1st Surgical Intervention – n=505 | ||

| First 5 days | 27 | |

| First 10 days | 37 | 0,000 A |

| First 15 days | 35 | |

| First 20 days | 40 | |

| After 20 days | 61 | |

| First 5 days | ||

| Yes | 27 | 0,000 T |

| No | 39 | |

| First 10 days | ||

| Yes | 33 | 0,003 T |

| No | 40 | |

| First 15 days | ||

| Yes | 34 | 0,000 T |

| No | 48 | |

| First 20 days | ||

| Yes | 34 | 0,000 T |

| No | 61 | |

| Documented Infection | ||

| Yes | 40 | 0,000 T |

| No | 20 | |

| Nosocomial Infection | ||

| Yes | 46 | 0,000 T |

| No | 19 | |

| Number of Documented Infections – n=328 | 0,000S | |

| Number of Documented Infections – n=328 | ||

| 1-2 Infections | 30 | |

| 3-4 Infections | 52 | 0,000 A |

| 5-6 Infections | 60 | |

| Over 6 Infections | 107 | |

| Mucocutaneous Infections | ||

| Yes | 41 | 0,000 T |

| No | 26 | |

| Respiratory Infection | ||

| Yes | 50 | 0,000 T |

| No | 27 | |

| Urinary Infection | ||

| Yes | 50 | 0,000 T |

| No | 22 | |

| Systemic Infection | ||

| Yes | 51 | 0,000 T |

| No | 24 | |

| Minimum Hemoglobin Value (g/dl) | 0,000 S | |

| Anemia (Hb < 8 g/dl) | ||

| Yes | 43 | 0,002 T |

| No | 28 | |

| Maximum Creatinine Value (mg/dl) | 0,002 S | |

| Acute Kidney Disease (Creatinine > 1,2 mg/dl) | ||

| Yes | 38 | 0,000 T |

| No | 28 | |

| Minimum Protein Value (g/l) | 0,000 S | |

| Hypoproteinemia (Total Protein < 60g/l) | ||

| Yes | 32 | 0,000 T |

| No | 19 | |

| Minimum Albumin value (g/l) | 0,000 S | |

| Hipoalbuminemia (Albumin < 35g/l) | ||

| Yes | 32 | 0.000 T |

| No | 16 | |

| Threat to Life | ||

| Very Low (ABSI 2-3) | 12 | |

| Moderate (ABSI 4-5) | 20 | |

| Moderately Severe (ABSI 6-7) | 29 | 0,000 A |

| Serious (ABSI 8-9) | 42 | |

| Severe (ABSI 10-11) | 73 | |

| Maximum (ABSI 12 ou Superior) | 42 | |

| Mortality > 50% according to ABSI (> 10) | ||

| Yes | 63 | 0,000 T |

| No | 27 | |

| Baux Score | 0,000S | |

| Modified Baux Score | 0,000S | |

| Mortality > 50% according to Modified Baux Score (≥ 140) | ||

| Yes | 55 | |

| No | 29 | |

| Death | ||

| Yes | 33 | 0,283 T |

| No | 29 |

Regarding the lesions, the following factors were associated with an increased length of stay: Thermal burns (p-value 0,000), especially if the thermal agent was fire (p-value 0,000); third-degree burns (p-value 0,000); need for mechanical ventilation (p-value 0,000); established airway injury (p-value 0,000); need for decompressive fasciotomies or escharotomies (p-value 0,000) and percentage of body area (p-value 0,000). Of importance is the comparison between early extubated patients (first 12 days) and non-early extubated, who had a significantly (p-value 0,000) longer length of stay (average of 28 vs 57 days).

The presence of associated traumatism was not significantly associated with an increased length of stay (p-value 0,125). (Table 2)

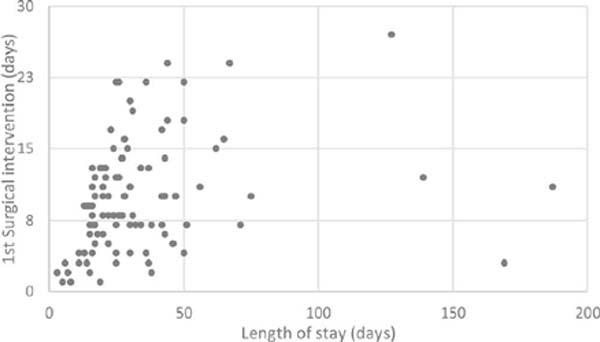

Appropriate debridement with or without grafting is the cornerstone of burn treatment. In our sample, the need for surgery was significantly associated with an increased length of stay (p-value 0,000), as was the timing of the surgery (p-value 0,000). Patients submitted to surgery in the first 5 days had an average length of stay of 27 days, however, when the surgery performed after the 20th day, the average stay was 61 days.

The presence of infection (p-value 0,000), the number of infections (p-value 0,000), and the presence of a nosocomial microorganism (p-value 0,000) were positively correlated with the length of stay. (Table 2).

The presence of anemia (p-value 0,002); renal failure (p-value 0,000), hypoproteinemia (p-value 0,000), and hypoalbuminemia (p-value 0,000) were also positively correlated with an increased length of stay.

The classic burn prognosis indexes such as the Abbreviated Burn Severity Index and the Modified Baux Score were strongly correlated with the length of stay (p-value 0,000).

DISCUSSION

The evolution of burn care has led to an increased survival rate of burn patients which has made some classic indexes outdated in terms of prognosis. On the other hand, length of stay is an objective variable, that is easy to measure and compare and is gaining more relevance as a metric in the assessment of quality of health care in burn patients. A more prolonged length of stay in a burn unit is associated with a greater number of infections, greater morbidity, greater mortality, and costs. Therefore, it is relevant to understand which factors contribute to the increase of this metric, to access potential actions to tackle this problem.

In our study, the average length of stay was 29 days, with a range from 1 to 254 days. Compared with the current literature12, this value is higher. However, in our unit, this data represents only the patients admitted in the Burn Care Unit, which is equivalated to an intensive care unit, and therefore most burns patients are severe and not amenable to standard infirmary care which most published studies focus on.

Similarly, to other studies, some factors associated with increased length of stay were: age, comorbidities, and burn severity-related factors, such as area of burnt skin, depth of burn, and need for decompressive escharotomy or fasciotomy. Inhalatory lesion is, in the current literature, the factor with the biggest impact on burn patients. In our cohort, the presence of airway injury with or without the need for mechanical ventilation was associated with an increase in length of stay. Similarly, early extubation was associated with a decreased length of stay.

Opposite to current literature, in our cohort female sex was associated with a statistically significant increased length of stay. This may be due to the older age of women averaged to man, leading to more burning in advanced age, where a more frail and dependent condition exists.

Timing of surgical debridement is a controversial topic in burn patient care13,14,15. Traditionally, a conservative approach with serial dressing changes, allows for the necrotic tissue to separate from the healthy wound bed which would later on be skin grafted. However, if this approach was prolonged, the constant release of pro-inflammatory factors would result in a systemic inflammatory state, which would aggravate the metabolic, immunologic, and systemic imbalance, leading to multiorgan failure and death. Furthermore, a greater delay in surgical debridement would often lead to the infection of the burnt areas, compounding the risk of death, and nefarious cicatricial problems such as hypertrophic scars or articular contractures that can impair a patient’s quality of life.

The presence of these scars, in aesthetically functional delicate areas may require further procedures to correct. Janzekovic16 described tangential debridement in 1970 and altered the burn patient surgical care paradigm. He proposed an earlier intervention with aggressive mechanical debridement and skin grafting11 to reduce the wound exposure time, reducing the metabolic stress, infection rate, and therefore, complications and mortality rate. Additionally, length of stay and consequentially, costs are reduced13. This was particularly true in patients without airway lesion14.

Some authors still defend a more delayed approach, claiming that a higher blood loss and consequentially a higher need for transfusion leads to further metabolic and hemodynamic distress. Additionally, some authors defend that early burn depth is difficult to ascertain, making the distinction of which areas will spontaneously heal and which will require debridement and grafting a hard decision in the first days, even for experienced burn surgeons. This difficulty stems from the heterogeneity of a burn, where it is common that a patient presents with lesions with different prognoses in continuity and often in a spotted pattern; and the fact that burns are an evolving lesion. The zone of stasis is an area that presents a potentially reversible area, and adequate fluid therapy and infection prevention can greatly improve the outcome of this area15. In sum, those who defend a delayed approach suggest that deferring the surgical approach for some days will allow a more accurate assessment and prevent unnecessary interventions.

In our cohort, which replicates the current literature, we have observed a direct proportional relation between the surgical timing of the first intervention and the length of stay. (Figure 1). Patients who were submitted to an earlier intervention had a shorter length of stay. This opens an avenue for better burn care – an earlier approach may provide a shorter length of stay, which might lead to a decreased infection risk, particularly nosocomial infection, and a reduction of costs. This approach has been shown to overcome the benefits of a delayed surgical intervention17,18.

In our cohort, multiple factors have been associated with a delayed first surgical intervention such as patients who are critically unstable to tolerate a surgical procedure, patients who have multiple small areas that heal favorably with dressing changes, lack of operating room time, and the need to delay surgery due to the use of oral anticoagulants.

Burn patients are susceptible to infection, especially by nosocomial multidrug-resistant organisms. In our cohort, 46% of patients were diagnosed with at least one infection. The average length of stay in patients who had an infection was 40 days, which contrasts with 20 days in patients who never had a microorganism identified in admission cultures or required any further septic workup. This difference is even greater when nosocomial infections (defined as an infection that develops in the first 48 hours after admission), where the average length of stay was 46 days.

Interestingly, this increased length of stay was independent of the affected system (mucocutaneous, urinary, hematologic, or bronchial). There, infection prevention is one area where significant improvements can translate into reduced length of stay, furthering the cause for the development of specific strategies for infection control and prevention.

Some laboratory results reflect a worsening clinical status and are also associated with an increased length of stay. Low hemoglobin (defined as a laboratory value of hemoglobin under 8.0g/dL); Renal Insufficiency (defined by serologic creatinine over 1,2mg/dL); hypoproteinaemia (defined by serologic protein inferior to 60g/L) and hypoalbuminemia (defined by serologic albumin inferior to 35g/L) were all statistically significant to predict an increased length of stay.

Classic prognosis indexes, such as the Abbreviated Burn Severity Index and the Modified Baux Score, include known morbidity influencing factors such as surface burnt area and airway lesion. As stated previously, these factors also have a strong correlation with the length of stay.

Intra-hospital mortality in Portugal remains comparatively high (7,7%)7 when compared with other countries from southern Europe, but it is steadily decreasing. In our cohort, mortality was 6%. Burn mortality rates are normally calculated based on the general population that suffered a burn injury. This group is heterogeneous and includes small burn areas, lesser severe burn degrees, and reflects mostly patients who are mostly treated with dressing change in an ambulatory clinic or with a short infirmary stay. The mortality rate in our cohort reflects only patients who were admitted to a Burnt Patient Special Care Unit.

As a final note, the author would like to acknowledge some study limitations. First, the study is retrospective in design, which does not allow patient randomization. Secondly, some possibly important factors were not assessed such as the need for transfusion, microorganism resistance pattern, and what antibiotic therapy was realized. Functional and aesthetic outcome scales were not accessed. Bigger, multicentric studies might allow better stratification of patients according to their burn surface area or patient co-morbidities, which might be able to combat the heterogeneity of this specific patient population and allow a more practical conclusion that is applicable daily.

CONCLUSIONS

This study allows us to state that variables related to higher burn severity, such as burnt area, need for mechanical ventilation, need for fasciotomy or escharotomy, airway injury, and the presence of third-degree burns have a significant effect on the length of stay. However, in the author’s opinion, the most relevant conclusion in this retrospective study is the confirmation that modifiable factors exist – such as time to first intervention and the number of documented infections – that can effectively reduce the length of stay. These two areas should be the focus of patient care to improve health-related outcomes.

The conclusion of our study is on par with current medical literature.

REFERENCES

1. Brusselaers N, Monstrey S, Vogelaers D, Hoste E, Blot S. Severe burn injury in Europe: a systematic review of the incidence, etiology, morbidity, and mortality. Crit Care. 2010;14(5):R188.

2. Galeiras R, Lorente JA, Pértega S, Vallejo A, Tomicic V, de la Cal MA, et al. A model for predicting mortality among critically ill burn victims. Burns. 2009;35(2):201-9.

3. Sheppard NN, Hemington-Gorse S, Shelley O P, Philp B, Dziewulski P. Prognostic scoring systems in burns: a review. Burns. 2011;37(8):1288-95.

4. Davydow DS, Katon WJ, Zatzick D F. Psychiatric morbidity and functional impairments in survivors of burns, traumatic injuries, and ICU stays for other critical illnesses: a review of the literature. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21(6):531-8.

5. Oncul O, Yüksel F, Altunay H, Açikel C, Celiköz B, Cavuşlu S. The evaluation of nosocomial infection during 1-year-period in the burn unit of a training hospital in Istanbul, Turkey. Burns. 2002;28(8):738-44.

6. Wanis M, Walker SAN, Daneman N, Elligsen M, Palmay L, Simor A, et al. Impact of hospital length of stay on the distribution of Gram negative bacteria and likelihood of isolating a resistant organism in a Canadian burn center. Burns. 2016;42(1):104-11.

7. Santos J V, Oliveira A, Costa-Pereira A, Amarante J, Freitas A. Burden of burns in Portugal, 200-2013: a clinical and economic analysis of 26,447 hospitalisations. Burns. 2016;42(4):891-900.

8. Bartosch I, Bartosch C, Egipto P, Silva A. Factors associated with mortality and length of stay in the Oporto burn unit (2006-2009). Burns. 2013;39(3):477-82.

9. Ho WS, Ying SY, Burd A. Outcome analysis of 286 severely burned patients: retrospective study. Hong Kong Med J. 2002;8(4):235-9.

10. Louise CN, David M, John SK. Is the target of 1 day length of stay per 1% total body surface area burned actually being achieved? A review of paediatric thermal injuries in South East Scotland. Int J Burns Trauma. 2014;4(1):25-30.

11. Orgill D P. Excision and skin grafting of thermal burns. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(9):893-901.

12. Burton KR, Sharma VK, Harrop R, Lindsay R. A population-based study of the epidemiology of acute adult burn injuries in the Calgary Health Region and factors associated with mortality and hospital length of stay from 1995 to 2004. Burns. 2009;35(4):572-9.

13. Munster AM, Smith-Meek M, Sharkey P. The effect of early surgical intervention on mortality and cost-effectiveness in burn care, 1978-91. Burns. 1994;20(1):61-4.

14. Ong YS, Samuel M, Song C. Meta-analysis of early excision of burns. Burns. 2006;32(2):145-50.

15. Mohammadi AA, Mohammadi S. Early excision and grafting (EE&G): Opportunity or threat? Burns. 2017;43(6):1358-9.

16. Janzekovic Z. A new concept in the early excision and immediate grafting of burns. J Trauma. 1970;10(12):1103-8.

17. Chong SJ, Kok YO, Choke A, Tan EWX, Tan KC, Tan BK. Comparison of four measures in reducing length of stay in burns: An Asian centre’s evolved multimodal burns protocol. Burns. 2017;43(6):1348-55.

18. Jansen LA, Hynes SL, Macadam SA, Papp A. Reduced length of stay in hospital for burn patients following a change in practice guidelines: financial implications. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33(6):e275-9.

1. Centro Hospitalar Universitário Lisboa Central,

Plastic Surgery - Lisboa - Lisboa - Portugal

2. Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Ocidental, Cirurgia

Plástica - Lisboa - Lisboa - Portugal

3. Hospital Garcia de Orta, Cirurgia Plastica -

Lisboa - Lisboa - Portugal

Corresponding author: Miguel João Ribeiro Matias Rua General Norton de Matos, 35, 5º, Esquerdo, Barreiro, Portugal. CEP: 2830-345 E-mail: miguelmatias@campus.ul.pt

Article received: June 11, 2023.

Article accepted: April 30, 2024.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter