Case Report - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Recurrent giant borderline phyllodes tumor: resection and breast reconstruction

Tumor filoide borderline gigante e recidivante: ressecção e reconstrução da mama

ABSTRACT

Phyllodes Tumor is a rare fibroepithelial neoplasm that represents 0.3 to 1% of all breast neoplasms. According to histopathologic classification, 12 to 26% are borderline type and approximately 15% of these tumors recur after surgical excision. The recommended treatment for all types of Phyllodes Tumor is surgical excision, and in the case of giant tumors, the treatment should be multidisciplinary. We present the case of a 46-year-old woman with a Phyllodes Tumor in the left breast that recurred 4 years after surgical excision. The anatomopathological study qualified it as a giant tumor and the histopathological study reported a Borderline Phyllodes Tumor. She underwent surgical excision with a left mastectomy and breast reconstruction employing a latissimus dorsi flap plus fat graft. The patient presented a favorable evolution without recurrence. In conclusion, the Recurrent Giant Borderline Phyllodes tumor is rare and its surgical management represents a challenge both in breast excision and reconstruction.

Keywords: Phyllodes Tumor. Mammaplasty. Surgical Flaps. Plastic Surgery Procedures. Mastectomy

RESUMO

O tumor filoide é uma neoplasia fibroepitelial rara que representa 0,3 a 1% de todas as neoplasias mamárias. De acordo com a classificação histopatológica, 12 a 26% são do tipo borderline e aproximadamente 15% desses tumores recorrem após excisão cirúrgica. O tratamento recomendado para todos os tipos de tumor filoide é a excisão cirúrgica, e no caso de tumores gigantes o tratamento deve ser multidisciplinar. Apresentamos o caso de uma mulher de 46 anos com tumor filoide na mama esquerda que recorreu 4 anos após a excisão cirúrgica. O estudo anatomopatológico qualificou-o como tumor gigante e o estudo histopatológico relatou tumor filoide borderline. Foi submetida a excisão cirúrgica com mastectomia esquerda e reconstrução mamária com retalho de grande dorsal mais enxerto de gordura. A paciente apresentou evolução favorável sem recidiva. Concluindo, o tumor filoide gigante borderline recorrente é raro e seu manejo cirúrgico representa um desafio tanto na excisão quanto na reconstrução mamária.

Palavras-chave: Tumor filoide; Mamoplastia; Retalhos cirúrgicos; Procedimentos de cirurgia plástica; Mastectomia

INTRODUCTION

Phyllodes tumor (PT) of the breast is a rare fibroepithelial neoplasm and represents less than 1% of all primary breast tumors1. Its incidence is approximately 2.1 per million population and occurs mostly in women aged 45-49 years2,3. PT generally has a rapid growth rate and measures between 4 to 7 cm, but when it reaches a size greater than 10 cm it is considered giant2.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), PTs are histopathological classified as benign, malignant, and borderline3. Borderline PT has a frequency of 12% to 26%1,3, a recurrence rate of 15% to 25%, and a low potential for metastasis4. Histopathologic features include a circumscribed or focally invasive borderline, frequent mitoses, and moderate and/or atypical stromal cellularity1.

The recommended treatment for all types of PT is surgical excision5. To avoid local recurrence, it is recommended to achieve a free margin of at least 1 cm. In general, tumors larger than 5 cm are treated by mastectomy5,6. However, the final treatment will depend on the histopathologic classification of the tumor, size, extent, and location. When deciding to perform a wide surgical resection of a Giant Borderline PT, it is necessary to consider different reconstructive techniques, either implant-based reconstruction (IBR) or autologous reconstruction (AR) based on flaps7. Quality of life, self-esteem and psychosocial wellbeing tend to improve in women who have undergone reconstructive surgery after mastectomy8.

We present the case of a 46-year-old woman with a Recurrent Giant Borderline PT in the left breast of approximately 40 cm in diameter, who underwent a wide resection with mastectomy and immediate breast reconstruction employing a latissimus dorsi flap (LDF) plus fat grafting injection and who had a favorable evolution after surgery without complications or recurrences.

CASE REPORT

A 46-year-old female patient, without comorbidities, with a history of lumpectomy for a PT in the left breast 4 years ago. Previously, she went to the consultation referring to a reappearance of the tumor in the left breast. On physical examination, a peri-areolar surgical scar was observed in the left breast in the upper outer quadrant and a hard, slightly mobile tumor approximately 8 cm in diameter was palpated. A biopsy was performed, which revealed recurrent PT. Due to the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic in Peru, contact with the patient was lost and the correct follow-up was not carried out.

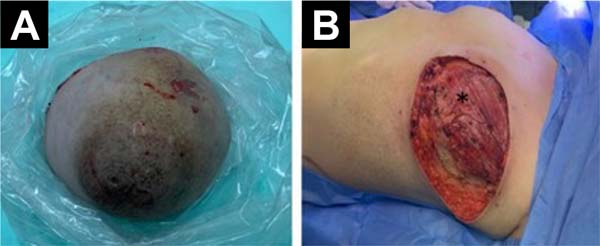

Nine months later, the patient came to the emergency room due to an increase in the size of the tumor and the presence of intense pain in the left breast. On physical examination, the left breast revealed pain on palpation, a slightly mobile tumor of approximately 40 cm in diameter, and erythema with collateral venous circulation (Figure 1).

The findings found in the ultrasound study were compatible with the BIRADS2 category, describing a vascularized, predominantly solid tumor with welldefined margins and cystic foci of approximately 15 cm. There was no evidence of distant metastases on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT). The initial histopathological results of the biopsy concluded the presence of fibroepithelial neoplasia with mild atypia, corresponding to a Borderline PT.

Because of the findings, it was decided to perform a left total mastectomy plus immediate breast reconstruction. The left total mastectomy was performed by the Gynecologic Oncology Service. Initially, a low axillary dissection and a Steward incision were performed, then an upper flap was formed with the inferior clavicular border as limit, and an inferior flap with the sub mammary sulcus, the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi and the sternal border as limits. Subsequently, the tumor tissue of the left breast was excised, dissecting down to the aponeurosis of the pectoralis major (Figure 2).

Lymphadenopathies of approximately 2 cm were found in axillary group I and the corresponding excision was performed. The histopathological characteristics of the postoperative specimen were consistent with a Borderline PT. Stromal overgrowth, moderate atypia, cambium layer, permeative borders, and mitotic count of 5/10 per 10 fields were evident. The surgical edges were larger than 1 mm concerning the tumor. The surrounding skin, nipple, and free terminal ducts had no signs of malignancy. Group I lymph nodes had no signs of malignancy.

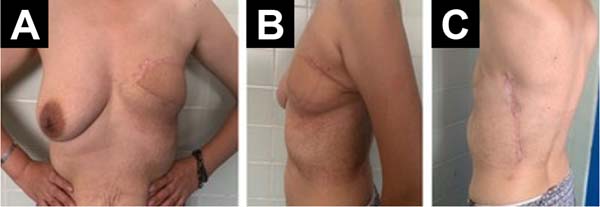

Breast reconstruction was performed by the Plastic Surgery Department. A pedicled myocutaneous flap of the latissimus dorsi plus fat graft was performed. To obtain the myocutaneous flap, an anterior skin incision was made up to the latissimus dorsi muscle. Subsequently, the latissimus dorsi muscle was separated from the serratus anterior and external oblique muscles, and an inferior approach was made up to the iliac crest insertions and finished with a posterior incision up to the thoracolumbar fascia over the latissimus dorsi muscle. The flap was raised from the distal to the proximal position to locate the latissimus dorsi pedicle (thoracodorsal artery) (Figure 3A). Subcutaneous tunneling and mobilization of the flap to the recipient site in the left hemithorax was performed. Both the donor and recipient areas were closed in planes (Figure 3B).

Hemovac drainage was placed at the end of the procedure to recover breast volume a fat graft was placed. A tumescent solution was infiltrated in the abdomen and a liposuction was performed, obtaining 300 cc of fat graft that was placed intramuscularly in the mobilized LDF and the mammary region. Finally, clean gauze and non-compressive elastic bandages were applied.

One week after surgery, the evolution of the flap was favorable with no areas of distress or local or systemic complications. The drains progressively decreased to less than 30 c.c.s of serohematic content and were removed. Hospital discharge was decided and weekly outpatient controls were indicated for one month. At one year, a CT scan was performed, which showed no signs of disease extension. Our patient is currently under close follow-up showing a favorable evolution with no local recurrence or distant metastasis (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

Early diagnosis and staging of PT are important for timely treatment2. PT is rapidly growing and delay in treatment can increase morbidity and mortality3. Due to social trust restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the shift of exclusive care for COVID-19 patients to higher-resolving hospitals, patient followup and contact was lost, leading to tumor overgrowth.

The mainstay of PT treatment is surgical excision5,9. When performing surgical excision, in addition to considering certain factors such as size, tumor extension, palpable lymph nodes, and free margins, it is necessary to consider aesthetics for subsequent reconstruction of the affected breast. Breast reconstruction is classified according to the type of procedure as IBR or AR7. Although the use of IBR is much more frequent, it was found that AR was associated with a better degree of satisfaction and sexual well-being compared to IBR, and it was also found that IBR has a higher risk of long-term reconstructive failure7. Therefore, in conjunction with the patient, we decided to perform RA instead of IBR.

In general, the RA depends on the anatomic region from which the flap originates. Among the most frequently used are the deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flap (DIEP), LDF, or transverse rectus abdominis myocutaneous (TRAM)7. The LDF provides a large amount of flexible soft tissue, anatomically the latissimus dorsi muscle is among the largest and strongest in the body, ischemic complications of the flap are rare due to the vascular supply provided by the thoracodorsal artery, the posterior perforator intercostal arteries, and the lumbar artery10.

The choice of the area to be used is determined by the patient’s body constitution, previous surgeries, and associated comorbidities. The use of the LDF is preferred in patients who are not candidates for the use of TRAM, due to previous abdominoplasty, previous TRAM, or insufficient abdominal skin and fat10. In our case, due to the patient’s abdominal fat and build, it was decided to use the LDF.

Concomitant to AR, fat grafting can also be performed in the area11. Among the benefits found with the use of fat grafting are: volume augmentation with more natural results and a higher degree of satisfaction without the need to use prosthetic devices11,12. In the context of autologous reconstruction, fat graft placement can be performed late or immediately after the transposition of the pedicled flap. Previously, a good volume gain was found in the area after immediate fat graft injection during the reconstructive procedure11. In our case, it was decided to perform a fat graft injection after mobilization of the LDF.

At present, few studies have reported reconstruction of Giant Borderline PT using AR and fat grafting. Wang et al.13 reported total mastectomy and resection of a 30 cm diameter Borderline PT, however, they did not report breast reconstruction. Liu et al.14 and Zhao et al.15 reported the possible association between hypoglycemia and Giant Borderline PT, in both cases radical mastectomies were performed, however, they also did not report any breast reconstruction. Tsuruta et al.16 reported the use of a DIEP flap for breast reconstruction after total mastectomy for Giant PT, however, they did not report the use of fat grafting.

Adjuvant therapy such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy has not been shown to decrease recurrence in PT9. The local recurrence rate is 10.9%, 14.4%, and 29.6% in benign, borderline, and malignant tumors respectively9. Therefore, it is reasonable to monitor for at least 3 years, especially in patients with PT with positive margins, by physical examination, ultrasound, or mammography17. In our patient, monthly controls were performed in the outpatient clinic, and at one year a control with CT was performed. There was no evidence of new masses or tumors in the operated area and an adequate clinical evolution was observed.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, Recurrent Giant Borderline PT is a rare pathology. Due to the restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, follow-up was lost, and timely treatment was not performed. Surgical management of these tumors is a challenge and treatment should be multidisciplinary. Breast reconstruction utilizing an LDF plus fat graft seems to be an attractive option to obtain positive aesthetic results.

ETHICS DECLARATIONS

Ethical approval: All procedures performed followed the ethical standards of Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, contained in the Declaration of Helsinki. In the present study, written informed consent was obtained from the patient. Patient consent: The patient provided written informed consent for the publication and the use of her images.

REFERENCES

1. Zhang Y, Kleer CG. Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast: Histopathologic Features, Differential Diagnosis, and Molecular/Genetic Updates. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(7):665-71.

2. Liang MI, Ramaswamy B, Patterson CC, McKelvey MT, Gordillo G, Nuovo GJ, et al.

3. Giant breast tumors: Surgical management of phyllodes tumors, potential for reconstructive surgery and a review of literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6(1):117.

4. World Health Organization; International Agency for Research on Cancer; Lakhani SR, Ellis IO, Schnitt SJ, Tan PH, van de Vijver MJ, eds. WHO classification of tumours of the breast. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2012.

5. Peneş NO, Pop AL, Borş RG, Varlas VN. Large borderline phyllodes breast tumor related to histopathology, diagnosis, and treatment management - case report. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2021;62(1):283-8.

6. Krings G, Bean GR, Chen YY. Fibroepithelial lesions; The WHO spectrum. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2017;34(5):438-52.

7. Simpson A, Li P, Dietz J. Diagnosis and management of phyllodes tumors of the breast. Ann Breast Surg. 2021;5:8-8.

8. Saldanha IJ, Cao W, Broyles JM, Adam GP, Bhuma MR, Mehta S, et al. Breast Reconstruction After Mastectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis [Internet]. Rockville: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2021. Available from: https://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/products/breast-reconstructionmastectomy/research

9. Howard-McNatt MM. Patients opting for breast reconstruction following mastectomy: an analysis of uptake rates and benefit. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2013;5:9-15.

10. Tan BY, Acs G, Apple SK, Badve S, Bleiweiss IJ, Brogi E, et al. Phyllodes tumours of the breast: a consensus review. Histopathology. 2016;68(1):5-21.

11. Sood R, Easow JM, Konopka G, Panthaki ZJ. Latissimus Dorsi Flap in Breast Reconstruction: Recent Innovations in the Workhorse Flap. Cancer Control. 2018;25(1):1073274817744638.

12. Turner A, Abu-Ghname A, Davis MJ, Winocour SJ, Hanson SE, Chu CK. Fat Grafting in Breast Reconstruction. Semin Plast Surg. 2020;34(1):17-23.

13. di Summa PG, Osinga R, Sapino G, Glen K, Higgins G, Tay S, et al. Fat grafting versus implant-based treatment of breast asymmetry, a single surgeon experience over 13 years: a paradigm shift? Gland Surg. 2021;10(6):1920-30.

14. Wang Q, Zheng K, Zhang L, Tan M, Li H, Zhang H, et al. The treatment process of an extremely rare giant borderline phyllodes tumor of breast: case report and literature review. Transl Cancer Res. 2021;10(4):1921-9.

15. Liu Y, Zhang M, Yang X, Zhang M, Fan Z, Li Y, et al. Severe Hypoglycemia Caused by a Giant Borderline Phyllodes Tumor of the Breast: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:871998.

16. Zhao J, Gao M, Ren Y, Cao S, Wang H, Ge R. A Giant Borderline Phyllodes Tumor of Breast With Skin Ulceration Leading to Non- Insular Tumorigenic Hypoglycemia: A Case Report and Literature Review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:651568.

17. Tsuruta Y, Karakawa R, Majima K, Yamamoto S, Shibata T, Yoshimatsu H, et al. The Reconstruction after a Giant Phyllodes Tumor Resection Using a DIEP Flap. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(4):e2760.

18. National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). NCCN Guidelines Special consideration: Phyllodes Tumor [Internet]. NCCN; 2022. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1419

1. Universidad Nacional de San Agustín de

Arequipa, Arequipa, Peru

Corresponding author: Elizbet Susan Montes-Madariaga Urb. José Luis Bustamante y Rivero, Cerro Colorado, Arequipa, Peru. E-mail: emontesma@unsa.edu.pe

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter