Original Article - Year 2024 - Volume 39 -

Facial trauma undergoing surgery: A 10-year epidemiological analysis in the interior of Brazil

O trauma de face submetido a cirurgia: Uma análise epidemiológica de 10 anos no interior do Brasil

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Facial trauma represents significant incapacitation for the victim, as well as a challenge for healthcare teams due to its complexity and involvement of important structures. Analyzing its epidemiology allows us to coordinate public health measures to improve care and prevention.

Method: Observational, descriptive, longitudinal study with a retrospective approach based on the medical records of patients who suffered facial trauma treated by the surgical clinic between 2010 and 2019.

Results: Among in individuals aged 20 to 29 years, which corresponds to 31.76% of total cases. It was also more common in males, corresponding to 78.45% of total cases. Car accidents were the most common cause, described in 22.31% of medical records, and the main fracture, present in 85.83% of cases, was of the bones of the nose.

Conclusion: Victims of oral and maxillofacial trauma treated at the Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro are predominantly men in their third decade of life, involved in automobile accidents, with injuries to the bones of the nose that were treated electively.

Keywords: Facial injuries; Analytical epidemiology; Facial bones; Plastic surgery procedures; Jaw fractures

RESUMO

Introdução: O trauma de face representa significativa incapacitação para a vítima, além de um desafio para as equipes de saúde devido a sua complexidade e envolvimento de estruturas nobres. Analisar a sua epidemiologia permite coordenar medidas em saúde pública para melhorar o atendimento e a prevenção.

Método: Estudo observacional, descritivo, longitudinal, com abordagem retrospectiva a partir dos prontuários dos pacientes vítimas de trauma de face atendidos pela clínica cirúrgica no período entre 2010 e 2019.

Resultados: Dentre os 529 prontuários incluídos no estudo e analisados, 71,08% tratava-se de cirurgias eletivas e o restante, 28,92%, de cirurgias de urgência. O trauma foi mais frequente em indivíduos de 20 a 29 anos, o que corresponde a 31,76% do total de casos. Também foi mais frequente em indivíduos do sexo masculino, correspondendo a 78,45% do total de casos. Acidentes automobilísticos foram a causa mais comum, descrita em 22,31% dos prontuários, e a principal fratura, presente em 85,83% dos casos, foi dos ossos próprios do nariz.

Conclusão: As vítimas de traumatismo bucomaxilofacial atendidas no Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro são predominantemente homens na terceira década de vida, envolvidos em acidentes automobilísticos, com lesões em ossos do nariz que foram abordadas de forma eletiva.

Palavras-chave: Traumatismos faciais; Epidemiologia analítica; Ossos faciais; Procedimentos de cirurgia plástica; Fraturas maxilomandibulares

INTRODUCTION

The panorama of trauma remains alarming in Brazil; of the ten main causes of death in the country’s population between the years 2000 and 2019, estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO), trauma was present in the fourth and eighth positions, respectively represented by interpersonal violence and traffic accidents. However, considering only deaths between 1 and 40 years of age, trauma leads to deaths, occupying all the first places with interpersonal violence, traffic accidents, self-inflicted injuries, and drownings1.

In addition to deaths, trauma is also cruel to survivors. There is a significant financial burden on the victim and their family, with incapacitation that generates billions in expenses for the health system, the social security system, and society as a whole2. For example, in 2016, traffic accidents alone caused 180,443 hospitalizations, at a cost of R$253.2 million for the SUS3.

In this context, head and facial traumas are among the most worrying, as they represent almost half of traumatic deaths, and many of these victims do not even survive to be treated. Facial trauma represents 7.4% to 8.7% of emergency care and requires expensive multidisciplinary work4.

It is essential to emphasize that the face is an anatomical region that presents many unique anatomical structures, responsible for essential functions such as chewing, swallowing, communication, and breathing5. Thus, traumatic injuries in this area become a survival challenge for the patient and a therapeutic challenge for health professionals, who need to reconstruct the functional and aesthetic aspects that sometimes require multiple surgical procedures4.

OBJECTIVE

Due to the relevance of facial trauma, its scientific understanding in its diverse regional realities becomes imperative, raising diagnoses and interventions that improve prevention and preparation of health services since controlling the quality of care is essential for the reduction of deaths and preventable complications6. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate the epidemiology of facial trauma care undergoing surgery at the Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro (HC-UFTM) in Uberaba-MG.

METHOD

The HC-UFTM Research Ethics Committee approved the study under opinion 4,940,424. This is an observational, longitudinal, and retrospective study conducted based on the analysis of the medical records of patients who suffered facial trauma and underwent surgery by the Plastic Surgery team at HC-UFTM between 2010 and 2019. The following information was selected for patients: age and sex, trauma mechanism, fractured bones, other traumatized body regions, number of surgeries, surgical procedure adopted, length of stay, and deaths.

After data collection, patient and trauma characteristics were statistically compared with the following outcomes: death, length of stay, and need for multiple surgeries. The descriptive evaluation was constructed using absolute frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean, standard deviation (mean ± SD), median, and percentiles for numerical variables. The analytical evaluation was carried out using Fisher’s exact test. The margin of error used in the statistical tests was 5%. The data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet, and the program used to obtain statistical calculations was IBM SPSS, version 23.

RESULTS

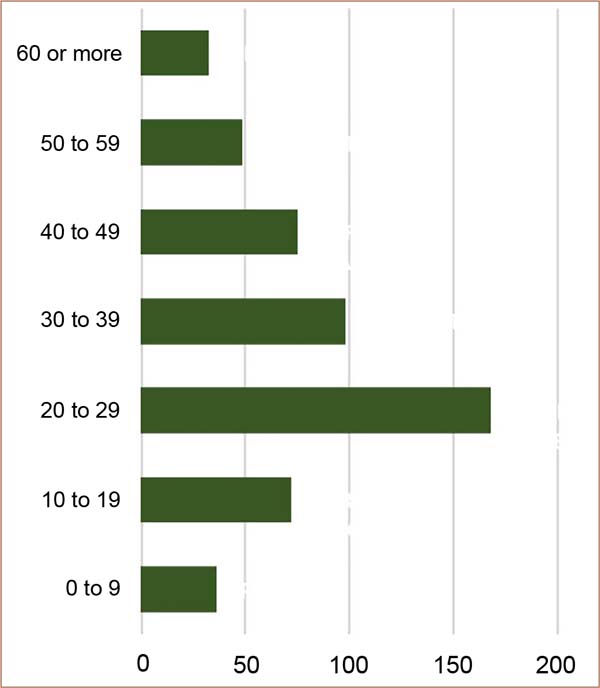

During the period from 2010 to 2019, 632 surgical procedures were found in 529 patients who were victims of facial trauma treated by the Plastic Surgery team at HC-UFTM. Among the 529 medical records included in the study and analyzed, 376 (71.08%) were previously scheduled surgeries, and the remainder, 153 (28.92%), were emergency surgeries. Regarding the sex of the patients, 415 (78.45%) were men and 114 (21.55%) were women. The age group was divided into 10 groups of 10 years, ranging from 0 to 99 years. Among these groups, trauma was more frequent in individuals aged 20 to 29 years, which corresponds to 168 (31.76%) of the total cases. The second most frequent group was 30 to 39 years old, with 98 (18.53%) cases, as shown in Graph 1.

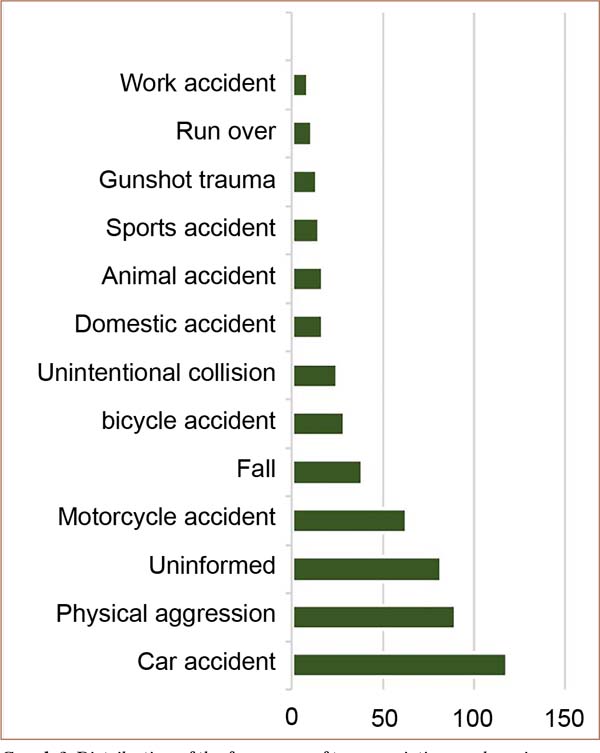

In relation to the etiology of the trauma, several groups of events were verified, with most incidents being automobile accidents (22.31%), assaults (17.01%), and motorcycle accidents (11.91%). In 82 (15.5%) of the medical records analyzed, the etiology of the patient’s facial trauma was not clearly stated, as shown in Graph 2.

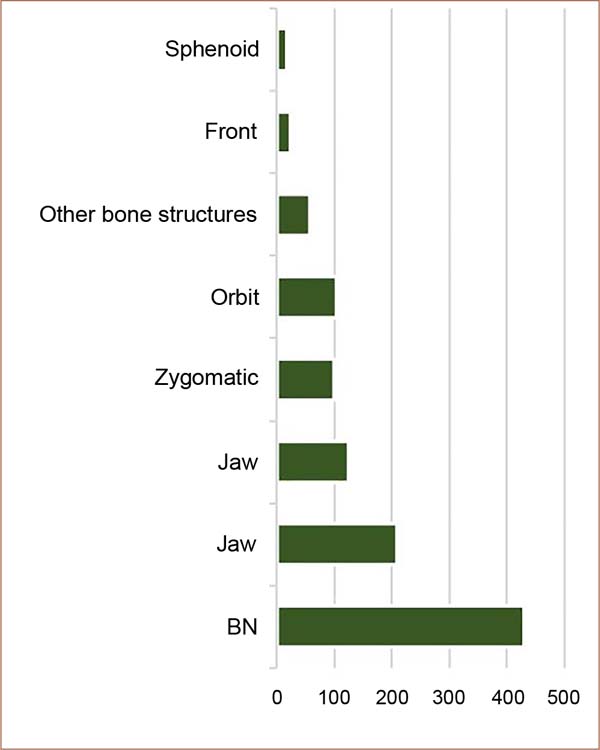

Another topic researched in the medical records was the presence and type of craniofacial fracture. In 28 (5.29%) of the medical records researched, no fractures were identified. In the remaining 501 (94.71%) cases, there was a fracture, and the most affected bones were bones of the nose (BN), with 430 (80%) cases, and the jaw, with 210 (39%) cases, according to shows Graph 3. In this context, in 319 (63.67%) of the cases, there was a fracture of just one facial bone, and in 182 (36.33%) more than one bone was fractured.

Another piece of information researched in the medical records was the existence of traumatic injuries in parts of the body other than the face. It was found that in 359 (67.86%) cases, the facial trauma was isolated, and in 161 (30.43%) cases, there was trauma in another region of the body. Furthermore, 9 (1.70%) records did not have information regarding this topic.

We also researched the surgical procedures performed on these patients. Thus, it was found that the most frequent surgery was to reduce nasal fractures, which appeared in 189 (35.72%) medical records, followed by osteosynthesis of complex jaw fractures, performed in 171 (32.33%) of patients. The third most performed procedure was osteosynthesis of complex panfacial fractures in 44 (8.32%) of the cases analyzed. The other procedures performed alone did not reach more than 5% incidence.

Furthermore, the number of procedures to which patients were subjected was also investigated. It was found that in 452 (85.44%) cases, only one surgery was necessary; in 71 (13.42%) cases, two surgeries were necessary; and in 6 (1.13%) patients, three or more surgeries were necessary. The length of stay was recorded in 524 of the 529 medical records, and the calculated average was 7 days.

DISCUSSION

Trauma represents one of the main public health problems in the world7, being the cause of death of around 5.8 million people per year8. Among these deaths, 50% result from trauma to the face and head2. In Brazil, the situation repeats itself, and trauma has a strong impact on the morbidity and mortality of the population9. In view of this, the relevance of facial trauma for health systems and for the definition of political actions regarding trauma treatment and prevention is undeniable.

Furthermore, a fundamental factor to be considered is that injuries to the facial region can considerably change the quality of life of those injured in terms of appearance and self-esteem10. Facial traumas have emotional, functional, and aesthetic repercussions and, therefore, if not properly treated, they leave consequences, marginalizing the individual from social life and generating incapacity for work11.

Regarding this data, it is important to highlight that the highest incidence found in this study and in the other studies analyzed was in the working age range, mainly in the third decade of life, as found by Ramos et al.2 and Cuéllar Gutiérrez et al.3

Regarding gender, this study found a significant prevalence of males compared to females, with 78.45% of patients being men. This finding corroborates other studies on this topic, which also showed a higher incidence of facial trauma in men, as attested by Pinheiro et al.12 The prevalence in males can be explained by the fact that men drive more frequently, as well as use drugs and get more involved in fights.13

The analysis of the etiology of the trauma found that the most frequent mechanism was the car accident, followed by physical aggression. This data corresponds to other studies in Brazilian literature on the topic carried out in large reference centers12,14,15.

Traffic-related etiologies (car accidents, motorcycle accidents, bicycle accidents, and being run over) together account for 41.78% of the cases in this study. The study conducted by Carvalho et al.11 observed a correlation between alcohol consumption and facial trauma resulting from a car accident in 41.1% of victims. However, as highlighted by Martins et al.16, this data is often neglected by the victim care team, which compromises the objectivity of this data in Brazilian literature. Other studies also found physical aggression as the second most frequent etiological factor in facial trauma2,16,17.

In relation to fractured bone structures, a very significant prevalence of the nasal bones (BN) was found, affected in 85.83% of cases, as shown by other studies on the subject2,18,19. Due to its prominence on the face, associated with the fragility of the nasal bone, the nose is more prone to fracture in facial trauma20 and is considered the most fractured structure by most authors12. In sequence, in order of prevalence, the mandible, maxilla, zygomaticus, and orbit were found.

The literature review showed that most studies did not verify the number of fractured bones in each patient, which is essential to evaluate the complexity of care2 and guide the management of victims from the first approach to rehabilitation. This work found that in 63.67% of cases, there was a fracture of just one facial bone, while in the remaining cases, more than one bone was fractured. This data corroborates the study by Ramos et al.2, which also verified the prevalence of only one fractured bone.

The existence of traumatic injuries in parts of the body other than the face was also investigated. It was found that in 67.86% of cases, the facial trauma was isolated, and in 30.43% of cases, there was trauma in another region of the body. This data is also very little explored in Brazilian literature, and few studies discuss it. According to Silva et al.4, traumatic brain injury is the non-facial injury most commonly associated with facial trauma. This analysis highlights the need for multidisciplinary work involving mainly the specialties of general surgery, ophthalmology, plastic surgery, oral and maxillofacial surgery, and neurosurgery in the care of victims of facial trauma4.

In relation to the number of procedures to which patients were subjected, it was found that in 85.44% of cases, only one surgery was necessary, and in 13.42% of cases, two surgeries were necessary; this is another data not analyzed by studies of facial trauma and which is directly related to the complexity of the service.

CONCLUSION

The individuals most frequently involved in facial trauma are men (78.45%) in the third decade of life - between 20 and 29 years old. The most prevalent etiologies of oral and maxillofacial trauma were traffic-related accidents, followed by physical assaults and falls. The most prevalent fractures were in the BN, mandible, and maxilla and required at least one surgery, with elective surgery being more common. Thus, with the data collected and analyzed, it is possible to coordinate public health measures in order to optimize care, treatment, and prevention of facial trauma.

REFERENCES

1. Macedo JLS, Camargo LM, Almeida PF, Rosa SC. Perfil epidemiológico do trauma de face dos pacientes atendidos no pronto socorro de um hospital público. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2008;35(1):9-13.

2. Ramos JC, Almeida MLD, Alencar YCG, de Sousa Filho LF, Figueiredo CHMDC, Almeida MSC. Epidemiological study of bucomaxilofacial trauma in a Paraíba reference hospital. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2018;45(6):e1978.

3. Cuéllar Gutiérrez JI, Prats Peña MC, Sanhueza Olea V, Reyes Court DA. Epidemiología del trauma maxilofacial, tratado quirúrgicamente en el Hospital de Urgencia Asistencia Pública: 3 años de revisión. Rev Cir. 2019;71(6):530-6.

4. Silva JJL, Lima AAAS, Melo IFS, Maia RCL, Pinheiro Filho TRC. Trauma facial: análise de 194 casos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2011;26(1):37-41.

5. Lentsck MH, Sato APS, Mathias TAF. Panorama epidemiológico de dezoito anos de internações por trauma em UTI no Brasil. Rev Saude Publica. 2019;53:83.

6. Costa CD, Scarpelini S. Avaliação da qualidade do atendimento ao traumatizado através do estudo das mortes em um hospital terciário. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2012;39(4):249-54.

7. Batista SEA, Baccani JG, Paula e Silva RA, Gualda KPF, Vianna Jr RJA. Análise comparativa entre os mecanismos de trauma, as lesões e o perfil de gravidade das vítimas, em Catanduva - SP. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2006;33(1):6-10.

8. Silveira ES, O’dwyer G. Centro de Trauma: modelo alternativo de atendimento às causas externas no estado do Rio de Janeiro. Saúde Debate. 2017;41(112):243-54.

9. Marano R, Jadjisky M, Mattos Filho AB, Mayrink G, Araújo S, Oliveira L, et al. Epidemiological Analysis of 736 Patients who Suffered Facial Trauma in Brazil. Int J Odontostomat. 2020;14(2):257-67.

10. Rosa GC, Baldasso RP, Fernandes MM, Delwing F, Oliveira RN. Trends in the valuation of injury involving the face: an analysis on trial in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Rev Gaúcha Odontol. 2020;68:e20200010.

11. Carvalho TB, Cancian LR, Marques CG, Piatto VB, Maniglia JV, Molina FD. Six years of facial trauma care: an epidemiological analysis of 355 cases. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;76(5):565-74.

12. Pinheiro LHZ, Silva BB, Basso RCF, Franco FF, Andrade TFC, Pili RC, et al. Perfil epidemiológico dos pacientes submetidos à cirurgia para tratamento de fratura de face em um hospital universitário. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2022;37(2):177-82.

13. Montovani JC, de Campos LM, Gomes MA, de Moraes VR, Ferreira FD, Nogueira EA. Etiology and incidence facial fractures in children and adults. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;72(2):235-41.

14. Vasconcelos B, Rodolfo Neto C, Silva A. Perfil epidemiológico de pacientes submetidos a tratamento cirúrgico no hospital de urgências de Goiânia - Hugo. In: Almeida DRMF, org. Odontologia: Tópicos em atuação odontológica. São Paulo: Editora Científica Digital; 2020. p. 115-35. DOI: 10.37885/201001800

15. Minari IS, Figueiredo CMBF, Oliveira JCS, Brandini DA, Bassi APF. Incidence of multiple facial fractures: a 20-year retrospective study. Res Soc Dev. 2020;9(8):e327985347.

16. Martins RHG, Ribeiro CBH, Fracalossi T, Dias NH. Reducing accidents related to excessive alcohol intake? A retrospective study of polytraumatized patients undergoing surgery at a Brazilian University Hospital. Rev Col Bras Cir. 2013;40(6):438-42.

17. Farias IPSE, Bernadino IM, Nóbrega LM, Grempel RG, D’Avila S. Maxillofacial trauma, etiology and profile of patients na exploratory study. Acta Ortop Bras. 2017;25(6):258-61.

18. Leite AC, Lima IJD, Leite RB. Perfil dos pacientes com fraturas maxilo-faciais atendidos em um hospital de emergência e trauma, João Pessoa, PB, Brasil. Pesq Bras Odontop Clín Integ. 2009;9(3):339-45.

19. Marques AC, Guedes LJ, Sizenando RP. Incidência e etiologia das fraturas de face na região de Venda Nova - Belo Horizonte, MG-Brasil. Rev Med Minas Gerais. 2011;20(4):500-2.

20. Motta MM. Análise epidemiológica das fraturas faciais em um hospital secundário. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2009;24(2):162-9.

1. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro,

Curso de Graduação em Medicina, Uberaba, MG, Brazil

2. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro,

Residência Médica em Cirurgia Plástica, Uberaba, MG, Brazil

3. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro,

Serviço de cirurgia oral e maxilofacial, Uberaba, MG, Brazil

4. Universidade Federal do Triângulo Mineiro,

Serviço de Cirurgia Craniomaxilofacial , Uberaba, MG, Brazil

Corresponding author: Marco Aurélio de Oliveira Marinho Avenida Leopoldino de Oliveira, 4488 - Sala 502, Uberaba, MG, Brazil, Zip Code: 38060-000, E-mail: marinhozztops@hotmail.com

Article received: August 25, 2023.

Article accepted: October 23, 2023.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter