Review Article - Year 2023 - Volume 38 -

What is the impact of capsulectomy on systemic symptoms attributed to silicone breast implants? Systematic literature review

Qual o impacto da capsulectomia nos sintomas sistêmicos atribuídos às próteses mamárias de silicone? Revisão sistemática da literatura

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Several studies have analyzed the possible relationship between silicone breast implants and systemic symptoms. Removal of breast implants with capsulectomy has been indicated in an attempt to improve these symptoms. The surgeon must have data based on the literature to inform the patient whether there is a relationship between the removal of a breast prosthesis with capsulectomy and improvement in symptoms, what is the rate of improvement, and how long it lasts.

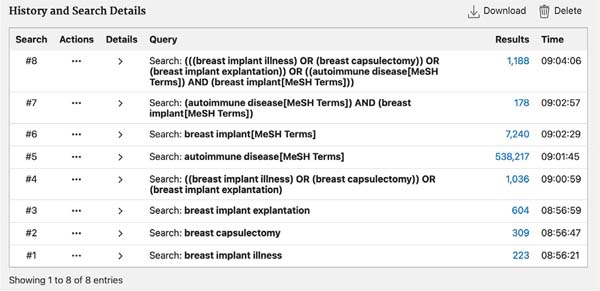

Method: A search was carried out in the Cochrane Library and PubMed virtual databases from January 1990 to April 2023. The search was carried out using a combination of free terms ("breast implant illness", "breast capsulectomy," and "breast implant explantation") and by using Boolean operators for Mesh descriptors such as [autoimmune diseases (MeSH Terms)] and [breast implant (MeSH Terms)].

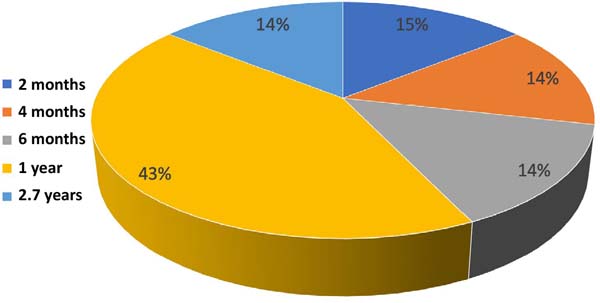

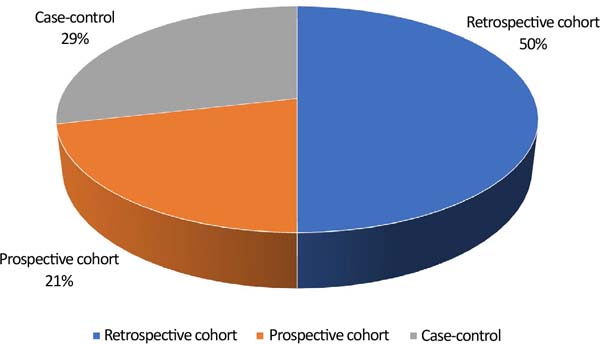

Results: 1,203 articles were obtained, 14 of which were selected for the study, consisting of 7 retrospective cohort articles, 3 prospective cohort articles, and 4 case-control articles. The improvement rate varied between 50 and 100% of cases, and the follow-up time varied between 2 months and 2.7 years. Several types of capsulectomies were performed in the studies, with similar rates of improvement.

Conclusion: There is evidence of improvement in systemic symptoms in patients with silicone breast implants who underwent breast implant removal with capsulectomy. The improvement in symptoms persisted during the period in which the patients were followed in the studies. More recent studies have demonstrated that the type of capsulectomy does not influence the improvement of systemic symptoms.

Keywords: Autoimmune diseases; Breast diseases; Mammaplasty; Breast implantation; Quality of life.

RESUMO

Introdução: Diversos estudos têm analisado a possível relação entre a prótese mamária de silicone e sintomas sistêmicos. A remoção das próteses de mama com capsulectomia tem sido indicada na tentativa de melhorar esses sintomas. É necessário que o cirurgião tenha dados embasados na literatura para informar ao paciente se há relação entre retirada de prótese de mama com capsulectomia e melhora dos sintomas, qual a taxa de melhora e por quanto tempo se mantém.

Método: Foi realizada pesquisa nos bancos de dados virtuais Cochrane Library e PubMed de janeiro de 1990 até abril de 2023. A busca foi realizada pela combinação de termos livres ("breast implant illness", "breast capsulectomy" e "breast implant explantation") e pelo uso de operadores booleanos para descritores Mesh como [autoimmune diseases (MeSH Terms)] e [breast implant (MeSH Terms)].

Resultados: Foram obtidos 1.203 artigos, sendo 14 selecionados para o estudo, consistindo em 7 artigos de coorte retrospectivo, 3 de coorte prospectivo e 4 caso-controle. A taxa de melhora variou entre 50 e 100% dos casos e o tempo de acompanhamento variou entre 2 meses e 2,7 anos. Diversos tipos de capsulectomia foram realizados nos estudos, com taxas semelhantes de melhora.

Conclusão: Há evidências de melhora dos sintomas sistêmicos em pacientes com prótese mamária de silicone submetidas a retirada de prótese de mama com capsulectomia. A melhora dos sintomas persistiu durante o período em que as pacientes foram acompanhadas nos estudos. Estudos mais recentes demonstraram que o tipo de capsulectomia não tem influência na melhora dos sintomas sistêmicos.

Palavras-chave: Doenças autoimunes; Doenças mamárias; Mamoplastia; Implante mamário; Qualidade de vida

INTRODUCTION

The breast prosthesis is one of the most studied medical devices regarding its safety 1 . Much research has been done on the possible relationship between silicone breast implants and rheumatic and autoimmune diseases 2 .

Several articles were unable to prove the relationship between silicone breast implants and connective tissue diseases, mainly due to confounding factors present in the studies 3 , 4 . In a meta-analysis, few well-designed and controlled studies were found to confirm this relationship 5 .

Systematic review studies of articles found an association between breast implants and a small increase in the risk of having Sjögren’s syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis 6 - 8 .

Within this review of articles, the largest study on the safety of prostheses was a 7-year retrospective follow-up of 100,000 patients undergoing breast prosthesis inclusion. In this study, it was concluded that Sjögren’s syndrome, scleroderma, and rheumatoid arthritis have a higher incidence in the population with breast prostheses compared to those without prostheses 9 . Local complications in the breasts are better described in the literature 10 .

The set of systemic symptoms observed in patients with silicone breast implants has been reported as human adjuvant disease, silicone-induced adjuvant disease, adjuvant-induced autoimmune disease (ASIA syndrome), and silicone implant incompatibility syndrome. The term silicone disease has become popular in the media, which can encompass systemic symptoms of autoimmune and rheumatic diseases, as well as symptoms of local complications such as capsular contracture 4 .

The most common symptoms were fatigue, memory loss, arthralgia, hair loss, dysphagia, depression, skin erythema, and headache. Symptoms related to breast implants are very similar, even in patients from different social conditions, races, and cultures. It is possible that lawsuits against the manufacturer of the breast prosthesis, psychosomatic illness, stress, somatization, or influence by the media cause these complaints 6 , 11 , 12 .

Therefore, demand for the procedure of prosthesis removal and total intact capsulectomy, popularized by the media as en bloc breast prosthesis explantation, has increased. In this surgery, the prosthesis is removed together with its capsule without breaking it 7 . The terminology “en bloc” is not the most correct, as it uses the term from oncological surgery, since “en bloc” means “removing healthy tissue to have a safety margin”, and in total intact capsulectomy, there is no safety margin, especially when the prosthesis is in the submuscular plane 8 .

Total intact capsulectomy has been indicated for patients with breast implants who present local or systemic symptoms in an attempt to improve these symptoms, and the justification for removing the capsule completely would be to avoid leaving silicone residues present in it 13 . Reconstruction options include breast fat grafting and mastopexy 14 .

To make decisions supported by Evidence-Based Medicine, it is necessary to have literature that indicates that total intact capsulectomy or some other variation of capsulectomy is beneficial for patients with breast implants and systemic symptoms. Otherwise, a simpler surgery could be offered, such as removing only the prosthesis without capsulectomy or using non-surgical treatments, such as herbal medicine, psychological support, and reassurance to the patient that the symptoms are not related to the implant 15 .

The surgeon should have data to inform which patients may experience improvement, the percentage and duration of this improvement, and whether there is a risk of recurrence.

OBJECTIVE

To carry out a systematic review of the medical literature evaluating the relationship between breast prosthesis removal and capsulectomy on systemic symptoms in patients with silicone breast implants.

METHOD

Search strategy for study identification

A search was carried out in the virtual databases Cochrane Library and PubMed, considering results between January 1990 and April 2023. This article was carried out by the author from January to April 2023 in the city of São Paulo-SP, and the Helsinki principles were followed.

The search was carried out by combining free terms (“breast implant illness”, “breast capsulectomy,” and “breast implant explantation”) and using Boolean operators for Mesh descriptors such as [autoimmune disease (MeSH Terms)] and [breast implant (MeSH Terms)] ( Figures 1 and 2 ). The Cochrane Sensitivity Maximizing Version strategy was used. There was no restriction on the language of the study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies that evaluated the relationship between capsulectomy in patients with silicone breast implants and systemic symptoms were included.

Studies that evaluated patients with a personal history of autoimmune or rheumatic diseases review articles, case reports, and articles that only evaluated laboratory changes or local symptoms, such as capsular contracture or rupture, were excluded. Studies that associated drug treatment with capsulectomy, patients who underwent only capsulotomy or who had been replaced by another prosthesis were also excluded.

Two independent researchers read the titles and abstracts, selecting articles according to the eligibility criteria. Disagreements between the inclusion of studies were resolved by consensus between the two researchers. The risks of bias in the studies were assessed using an instrument similar to that used by the Cochrane Collaboration.

RESULTS

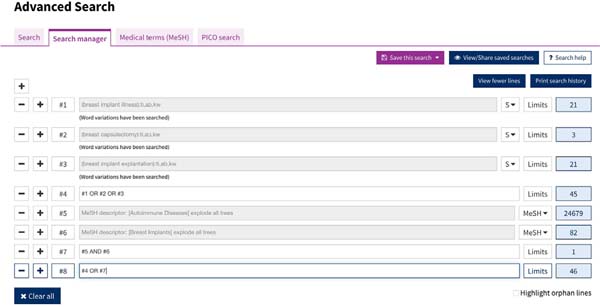

One thousand one hundred eighty-eight studies were obtained from the PubMed database and 46 studies from the Cochrane Library following the search strategy described in Methods, for a total of 1,234 studies. Eliminating repeated studies in both databases, the total number of studies obtained was 1,203.

After reading the titles and/or summaries, 1,116 articles were excluded following the eligibility criteria. Eighty-seven articles were selected for full reading, and after the selection process, 14 articles were included in the study, 10 of which were cohort studies and 4 were control cases ( Figure 3 ).

Of the 87 articles selected for full reading, 23 were excluded because they only evaluated local complications of breast prostheses, 17 because they evaluated patients undergoing breast reconstruction, 15 because they were review articles, 8 because they associated immunosuppressive medications in the treatment, 6 were editorial letters and 4 case reports.

According to Table 1 , during the analysis, the following were observed: study design, case series, most frequent symptoms, and the percentage of improvement in symptoms after capsulectomy.

| Reference | Kind of study | N | Symptoms | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melmed 11 | Retrospective cohort | 240 | fatigue, arthralgia, depression, memory loss |

Improvement in 74% of cases |

| Rohrich et al. 15 | Retrospective cohort | 50 | fatigue, arthralgia, headache | Improvement in 50% of cases |

| Svahn et al. 16 | Retrospective cohort | 63 | fatigue, arthralgia, memory loss | Improvement in 78% of cases |

| Vasey et al. 17 | Retrospective cohort | 33 | fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia | Improvement in 73% of patients |

| Wee et al. 18 | Retrospective cohort | 750 | fatigue, arthralgia, memory loss | Improvement in 100% of cases |

| Katsnelson et al. 19 | Retrospective cohort | 248 | fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia | Improvement in 90% of cases |

| Metzinger et al. 20 | Retrospective cohort | 200 | fatigue, myalgia, breast pain | Improvement in 96% of cases |

| Peters et al. 21 | Prospective cohort | 75 | arthralgia, myalgia, breast pain | Improvement in 74% of cases |

| Maijers et al. 22 | Prospective cohort | 52 | fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, night sweats, injuries dermatological | Improvement in 69% of cases |

| Bird & Niessen 23 | Prospective cohort | 140 | fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia | Improvement in 100% of cases |

| Rohrich et al. 24 | Case-control | 38 casos/ 38 controle |

fatigue, myalgia, arthralgia |

100% improvement in cases |

| Walden et al. 25 | Case-control | 22 casos/ 20 controle |

arthralgia, skin lesions | Improvement in 100% of cases |

| Glicksman et al. 26 | Case-control | 50 casos/ 100 controle |

fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia | Improvement in 94% of cases |

| Glicksman et al. 27 | Case-control | 50 casos/ 100 controle |

Fatigue, anxiety, memory loss | Improvement in 94% of cases |

N = number of patients.

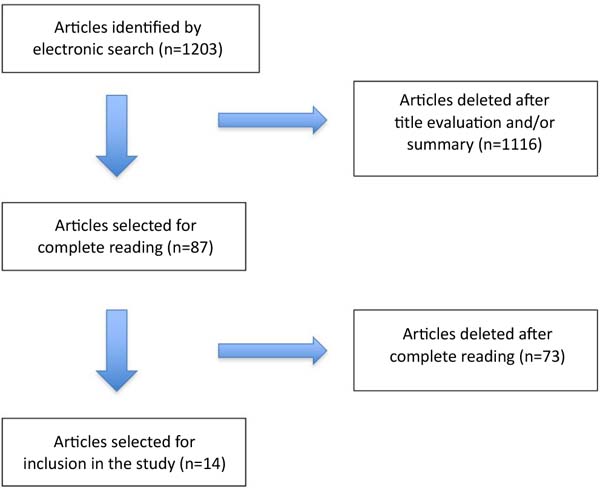

The percentage of improvement in symptoms was observed considering all studies and by type of study ( Figure 4 ).

Figure 5 shows the percentage of studies according to follow-up time. Only prospective studies such as prospective cohort and case-control were considered.

Figure 6 demonstrates the percentage of study types included in the review.

DISCUSSION

The removal of breast prostheses and capsules has been an increasingly requested surgery in recent years. Part of this is influenced by the recall of a prosthesis brand, changes in patients’ lifestyles, and the dissemination on social media of possible associations between breast prostheses and various symptoms.

In addition to systemic symptoms, patients removed their prostheses for fear of complications such as rupture, aesthetic reasons, and fear of needing additional surgeries at an older age. A study showed that the most satisfied patients were those who removed the breast implant due to fear of the long-term consequences of having a foreign body 28 . It is important to remember that it is necessary to distinguish local complications of the prosthesis (rupture, seroma, contracture) from systemic symptoms 4 .

One of the reasons for performing a capsulectomy lies in the theory that the biofilm that surrounds the capsule and the prosthesis would be related to systemic symptoms and local complications such as contracture. Biofilm is a layer of bacteria adhered to the silicone surface. This theory is controversial since the capsule is not an absolute barrier to these bacteria, the most common being Propionibacterium - in addition to these bacteria being naturally found in other regions of the body 29 - 31 .

Another reason is the reduction of seromas, palpability, and removal of traces of silicone present in the capsules 32 . There is also the theory that the increase in the inflammatory response associated with the breast implant and its capsule would be related to systemic symptoms, capsular contracture, BIA-ALCL, and as a trigger for the appearance of autoimmune diseases in predisposed patients 18 , 19 , 33 , 34 . A case-control study found that 3 (IL-13, IL17A, and IL22) of the 12 cytokines studied were higher in the group of patients with breast prostheses and systemic symptoms when compared to control groups 31 .

Another argument for removing the capsules would be that they would contain a greater amount of heavy metal from breast implants, such as zinc, copper, nickel, and others. However, no statistically significant differences were found in heavy metals in the capsules of patients with silicone prostheses between the groups with systemic symptoms and the group without symptoms. Furthermore, no toxic levels of heavy metals were found in any patient in the study groups 35 .

All included studies were consistent in demonstrating improvement in systemic symptoms in patients undergoing breast prosthesis removal and various types of capsulectomies. It is important to highlight that the capsulectomy can be total intact, total, or partial. In intact total capsulectomy, the capsule is removed without tears or holes together with the prosthesis. In total capsulectomy, the prosthesis can be removed first and then the capsule removed in its entirety.

The follow-up time of patients in prospective cohort and case-control studies ranged from 2 months to 2.7 years. The improvement in symptoms was maintained throughout the postoperative follow-up period in studies without recurrences 21 - 27 .

In the studies selected in this systematic review, the most frequent symptoms were arthralgia, myalgia, fatigue, and memory loss. The improvement in systemic symptoms with capsulectomy ranged from 50% to 100% in cohort studies and from 94% to 100% in case-control studies 36 , 37 .

There is a greater percentage of improvement in patients without a diagnosis of rheumatological or autoimmune disease when compared to patients with these diseases. The greater the number of symptoms preoperatively, the greater the number of symptoms that will improve postoperatively 33 .

Patients who reported systemic symptoms related to the prostheses showed statistically significant improvement after removal of the prostheses and capsulectomy; these improvements persisted for 6 to 12 months 23 , 26 . The improvement was observed regardless of the type of capsulectomy performed, whether total intact, total, or partial 26 , 27 , 35 . One study evaluated laboratory changes and also did not identify any difference between the groups that underwent total intact, total, or partial capsulectomy 31 .

Most of the studies were cohort studies, 7 retrospective and 3 prospective, and 4 case-control studies.

Retrospective cohort study

Melmed11 performed prosthesis removal with capsulectomy in 240 patients. Capsular contracture was the main complaint, in addition to fatigue, arthralgia, and memory loss. Silicone was found in the pathological anatomy results in all the capsules removed. Improvement in systemic symptoms occurred in 74% of patients.

Rohrich et al. 15 observed that no isolated or paired complaint was associated with predicting the outcome, making it difficult to correlate subjective preoperative complaints with improved quality of life after capsulectomy. Patients who reported five or fewer medical symptoms before explantation were more likely to notice an improvement in quality of life after surgery than patients who had nine or more complaints.

Svahn et al. 16 found that 81% of patients were satisfied with the result of prosthesis removal with capsulectomy. There was an improvement in quality of life in 78% of cases. Surgery resulted in the worsening of the condition in 3% of cases and did not change the condition in 19%.

Vasey et al. 17 observed that, in the group of 17 patients who chose not to remove the prosthesis, there was no change in symptoms. In the group of 33 patients who underwent capsulectomy, 24 of them had improvement in symptoms; in eight, the symptoms did not improve, and in one, the symptoms worsened.

Wee et al. 18 retrospectively analyzed data from 750 patients undergoing capsulectomy, using data from questionnaires filled out by the patients themselves regarding the evolution of 11 symptoms most frequently reported before and after surgery. They found improvement in all 11 symptoms, which began before the first 30 days after surgery and continued after this period.

Katsnelson et al. 19 carried out a cohort study on 248 patients with systemic symptoms attributed to silicone disease who underwent prosthesis removal and capsulectomy, reporting improvement in symptoms in 90.4% of patients.

Metzinger et al. 20 carried out a retrospective cohort study between 2016 and 2020 with 200 patients with systemic symptoms who underwent prosthesis removal with capsulectomy and observed an improvement in symptoms in 96% of patients after the procedure.

Prospective cohort study

Peters et al. 21 analyzed 100 patients undergoing capsulectomy, but only 75 patients responded to the questionnaire. An improvement in symptoms was observed in 56 of the patients after an average follow-up of 2.7 years.

Maijers et al. 22 identified that 75% of patients reported pre-existing allergies to breast implants, suggesting a possible intolerance to silicone and other substances. In this case, removal of the prosthesis with capsulectomy improved symptoms in 69% of cases.

Bird & Niessen 23 carried out a prospective cohort study on 140 patients with systemic symptoms who underwent prosthesis removal and capsulectomy and identified improvements in symptoms in all patients in the study.

Case-control

Rohrich et al. 24 tried to determine if there was any preoperative parameter that could determine which patients could have their symptoms improved after capsulectomy. They found statistically significant evidence that intact total capsulectomy improves subjective complaints, especially musculoskeletal complaints.

Walden et al. 25 compared three groups: patients undergoing capsulectomy, patients undergoing cholecystectomy, and patients not undergoing surgery (control group). When evaluating rates of depression and self-esteem in the groups, higher rates of anxiety and depression were observed in patients undergoing capsulectomy, in addition to lower rates of satisfaction with their breasts.

Glicksman et al. 26 carried out a case-control study on 150 patients divided equally into three groups: patients with systemic symptoms requesting prosthesis removal and capsulectomy, patients without symptoms requesting prosthesis removal and capsulectomy, and patients undergoing mastopexy who had never used a prosthesis. In the study, the group of women with systemic symptoms who underwent prosthesis removal and capsulectomy had improvement in symptoms regardless of the type of capsulectomy performed.

Glicksman et al. 27 carried out a case-control study with three groups of 50 patients, each followed for 1 year. In this study, it was observed that the improvement in symptoms was maintained for 1 year after surgery to remove the prosthesis with capsulectomy.

Criticisms of studies

The selected cohort studies did not present data with the population adjusted for age, comorbidity, and personal and family history. Many studies placed patients undergoing intact, total, and partial capsulectomies in the same group or did not identify the type of capsulectomy performed.

Most cohort studies were retrospective and had small populations with short follow-up times. The ideal would be prospective cohort studies, with a larger population, adjusted by parameters and followed over a long term 20 .

Total intact capsulectomy involves risks, the main one being hematoma (1.6%), followed by infection (0.5%). The incidence of hematoma in capsulectomies is higher when compared to prosthesis removal without capsulectomy (2.8% vs. 1.9%) or implant exchange without capsulectomy (1.6% vs. 0.9%, respectively) 38 .

Due to the risks involved in capsulectomy, it is important to verify whether the improvements observed in the studies could not be obtained with minor surgeries, such as simply removing the prosthesis or capsulotomy.

In this review, the rate of symptom improvement was not compared between patients who only had a breast prosthesis removed and those who had a breast prosthesis removed with capsulectomy.

Patients with symptoms who sought prosthesis removal with capsulectomy had higher levels of somatization, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, and anxiety 39 . It should be assessed whether there is a group of patients predisposed to presenting systemic symptoms after the inclusion of a breast prosthesis.

The ideal would be to create a score to predict which patients are most at risk of developing systemic symptoms when undergoing a breast prosthesis. Along the same lines, it would be useful to have a score to identify which patients with breast prosthesis implants and systemic symptoms could show the highest rates of improvement after breast prosthesis removal and capsulectomy.

CONCLUSION

The medical literature presents evidence that there is consistent improvement in systemic symptoms in patients with silicone breast implants who undergo breast implant removal with capsulectomy. The improvement in symptoms persisted during the period in which the patients were followed in the studies.

More recent studies have demonstrated that the type of capsulectomy does not influence the improvement of systemic symptoms.

REFERENCES

1. Marano AA, Cohen MH, Ascherman JA. Resolution of Systemic Rheumatologic Symptoms following Breast Implant Removal. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(5):e2828.

2. Lipworth L, Holmich LR, McLaughlin JK. Silicone breast implants and connective tissue disease: no association. Semin Immunopathol. 2011;33(3):287-94.

3. Tugwell P, Wells G, Peterson J, Welch V, Page J, Davison C, et al. Do silicone breast implants cause rheumatologic disorders? A systematic review for a court-appointed national science panel. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(11):2477-84.

4. Magnusson MR, Cooter RD, Rakhorst H, McGuire PA, Adams WP Jr, Deva AK. Breast Implant Illness: A Way Forward. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;143(3S A Review of Breast Implant-Associated Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma):74S-81S.

5. Janowsky EC, Kupper LL, Hulka BS. Meta-analyses of the relation between silicone breast implants and the risk of connective-tissue diseases. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(11):781-90.

6. Dush DM. Breast implants and illness: a model of psychological factors. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(7):653-7.

7. Meiega JM, Amaral AB, Cunha KN, Arantes HL, Kawasaki MC. Capsulectomy without Capsulotomy for Treating Capsule Contractures. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2001;16(2):37-48.

8. Gerzenshtein J. The Dishonesty of Referring to Total Intact Capsulectomy as “En Bloc” Resection or Capsulectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145(1):227e-8e.

9. Coroneos CJ, Selber JC, Offodile AC 2nd, Butler CE, Clemens MW. US FDA Breast Implant Postapproval Studies: Long-term Outcomes in 99,993 Patients. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):30-6.

10. Rohrich RJ, Kaplan J, Dayan E. Silicone Implant Illness: Science versus Myth? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144(1):98-109.

11. Melmed EP. A review of explantation in 240 symptomatic women: a description of explantation and capsulectomy with reconstruction using a periareolar technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(5):1364-73.

12. Ahern M, Smith M, Chua H, Youssef P. Breast implants and illness: a model of psychological illness. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61(7):659.

13. Copeland M, Kressel A, Spiera H, Hermann G, Bleiweiss IJ. Systemic inflammatory disorder related to fibrous breast capsules after silicone implant removal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92(6):1179-81.

14. Rohrich RJ, Beran SJ, Restifo RJ, Copit SE. Aesthetic management of the breast following explantation: evaluation and mastopexy options. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(3):827-37.

15. Rohrich RJ, Rathakrishnan R, Robinson JB Jr, Griffin JR. Factors predictive of quality of life after silicone-implant explanation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(5):1334-7.

16. Svahn JK, Vastine VL, Landon BN, Dobke MK. Outcome of mammary prostheses explantation: a patient perspective. Ann Plast Surg. 1996;36(6):594-600.

17. Vasey FB, Havice DL, Bocanegra TS, Seleznick MJ, Bridgeford PH, Martinez-Osuna P, et al. Clinical findings in symptomatic women with silicone breast implants. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1994;24(1 Suppl 1):22-8.

18. Wee CE, Younis J, Isbester K, Smith A, Wangler B, Sarode AL, et al. Understanding Breast Implant Illness, Before and After Explantation: A Patient-Reported Outcomes Study. Ann Plast Surg. 2020;85(S1 Suppl 1):S82-6.

19. Katsnelson JY, Spaniol JR, Buinewicz JC, Ramsey FV, Buinewicz BR. Outcomes of Implant Removal and Capsulectomy for Breast Implant Illness in 248 Patients. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(9):e3813.

20. Metzinger SE, Homsy C, Chun MJ, Metzinger RC. Breast Implant Illness: Treatment Using Total Capsulectomy and Implant Removal. Eplasty. 2022;22:e5.

21. Peters W, Smith D, Fornasier V, Lugowski S, Ibanez D. An outcome analysis of 100 women after explantation of silicone gel breast implants. Ann Plast Surg. 1997;39(1):9-19.

22. Maijers MC, de Blok CJ, Niessen FB, van der Veldt AA, Ritt MJ, Winters HA, et al. Women with silicone breast implants and unexplained systemic symptoms: a descriptive cohort study. Neth J Med. 2013;71(10):534-40.

23. Bird GR, Niessen FB. The effect of explantation on systemic disease symptoms and quality of life in patients with breast implant illness: a prospective cohort study. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):21073.

24. Rohrich RJ, Kenkel JM, Adams WP, Beran S, Conner WC. A prospective analysis of patients undergoing silicone breast implant explantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105(7):2529-37; discussion 38-43.

25. Walden KJ, Thompson JK, Wells KE. Body image and psychological sequelae of silicone breast explantation: preliminary findings. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(5):1299-306.

26. Glicksman C, McGuire P, Kadin M, Lawrence M, Haws M, Newby J, et al. Impact of Capsulectomy Type on Post-Explantation Systemic Symptom Improvement: Findings From the ASERF Systemic Symptoms in Women-Biospecimen Analysis Study: Part 1. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42(7):809-19.

27. Glicksman C, McGuire P, Kadin M, Barnes K, Wixtrom R, Lawrence M, et al. Longevity of Post-Explantation Systemic Symptom Improvement and Potential Etiologies: Findings From the ASERF Systemic Symptoms in Women-Biospecimen Analysis Study: Part 4. Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43(10):1194-204.

28. Slavin SA, Goldwyn RM. Silicone gel implant explantation: reasons, results, and admonitions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;95(1):63-9.

29. Swanson E. Breast Implant Illness, Biofilm, and the Role of Capsulectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2020;8(7):e2999.

30. Swanson E. The Case for Breast Implant Removal or Replacement Without Capsulectomy. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2021;45(3):1338-41.

31. McGuire P, Glicksman C, Wixtrom R, Sung CJ, Hamilton R, Lawrence M, et al. Microbes, Histology, Blood Analysis, Enterotoxins, and Cytokines: Findings From the ASERF Systemic Symptoms in Women-Biospecimen Analysis Study: Part 3. Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43(2):230-44.

32. Manahan MA. Adjunctive Procedures and Informed Consent with Breast Implant Explantation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(5S):51S-7S.

33. Magno-Padron DA, Luo J, Jessop TC, Garlick JW, Manum JS, Carter GC, et al. A population-based study of breast implant illness. Arch Plast Surg. 2021;48(4):353-60.

34. Nahabedian MY. The Capsule Question: How Much Should Be Removed with Explantation of a Textured Device? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147(5S):44S-50S.

35. Wixtrom R, Glicksman C, Kadin M, Lawrence M, Haws M, Ferenz S, et al. Heavy Metals in Breast Implant Capsules and Breast Tissue: Findings from the Systemic Symptoms in Women-Biospecimen Analysis Study: Part 2. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42(9):1067-76.

36. de Boer M, Colaris M, van der Hulst RRWJ, Cohen Tervaert JW. Is explantation of silicone breast implants useful in patients with complaints? Immunol Res. 2017;65(1):25-36.

37. Swanson E. Does a Capsulectomy Really Improve Pulmonary Function in Women with Breast Implant Illness? Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(11):e3892.

38. Afshari A, Nguyen L, Glassman GE, Perdikis G, Grotting JC, Higdon KK. Incidence and Preoperative Risk Factors for Major Complications After Capsulectomy: Analysis of 3048 Patients. Aesthet Surg J. 2022;42(6):603-12.

39. Wells KE, Roberts C, Daniels SM, Hann D, Clement V, Reintgen D, et al. Comparison of psychological symptoms of women requesting removal of breast implants with those of breast cancer patients and healthy controls. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;99(3):680-5.

1. Consultório particular, São Paulo, SP,

Brazil

Corresponding author: Ricardo Eustáchio de Miranda Rua Bandeira Paulista, 530, sala 43, São Paulo, SP, Brazil, Zip Code: 04532-011, E-mail: ricardomiranda@hotmail.com

Article received: May 09, 2023.

Article accepted: June 13, 2023.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter