Original Article - Year 2023 - Volume 38 -

Electrical burns: Epidemiological analysis of patients at the Burns Unit of the Hospital de Clínicas of the Federal University of Uberlândia

Queimadura elétrica: Análise epidemiológica dos pacientes da Unidade de Queimados do Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Using electric current is essential in our daily activities; however, its contact with living tissue can cause mild to severe or fatal burns. As it is a public health problem, knowledge of its epidemiology is essential for the development of health programs.

Method: Cross-sectional study of data recorded in the medical records of patients treated for electrical burns at the Burns Unit of the Hospital de Clínicas of the Universidade Federal de Uberlândia between 2013 and 2019.

Results: 26 patients were admitted, the majority of whom were male (76 .9%) and adults (30.7%), victims of high voltage current (65.4%) at work (57.7%), which most affected the upper extremities (80.7%), with children all female (15.3%). The average percentage of burned area was 14. 5% and the % of those treated with skin autograft was 53.8%. The average hospital stay was 40 days, and 3.8% went to the Intensive Care Unit. No deaths were recorded during the period.

Conclusion: The incidence of patients treated for electrical burns is low, affecting victims in all age groups and with a predominance of adult males in their workplace. The most common surgical treatment was skin autograft. Health promotion, prevention, and protection policies regarding the dangers of electrical currents would not be practiced and disseminated among our domestic, working, or employing population, unlike what occurs in most developed countries.

Keywords: Burns; Burns, electric; Burn units; Epidemiology; Brazil.

RESUMO

Introdução: O uso da corrente elétrica é imprescindível nas nossas atividades do

cotidiano, porém, seu contato com tecidos vivos pode provocar queimaduras

desde leves até graves ou fatais. Por se tratar de um problema de saúde

pública, o conhecimento de sua epidemiologia é essencial para o

desenvolvimento de programas em saúde.

Método: Estudo transversal de dados registrados nos prontuários dos pacientes

atendidos por queimadura elétrica na Unidade de Queimados do Hospital de

Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia entre os anos de 2013 e

2019.

Resultados: Foram admitidos 26 pacientes, a maioria de sexo masculino (76,9%) e adultos

(30,7%), vítimas de corrente de alta voltagem (65,4%) no trabalho (57,7%),

que mais afetou as extremidades superiores (80,7%), sendo as crianças todas

do sexo feminino (15,3%). O percentual médio de área queimada foi de 14,5% e

o percentual de tratados com autoenxerto de pele foi de 53,8%. A média de

permanência hospitalar foi de 40 dias e 3,8% deles foram para a Unidade de

Terapia Intensiva. Não se registraram óbitos durante o período.

Conclusão: A incidência de pacientes atendidos por queimadura elétrica é baixa,

acometendo vítimas em todas as faixas etárias e com predomínio em indivíduos

adultos do sexo masculino em seu local de trabalho. O tratamento cirúrgico

mais realizado foi o autoenxerto de pele. As políticas de promoção,

prevenção e proteção em saúde no que diz respeito aos perigos da corrente

elétricas não estariam sendo praticadas e difundidas em nossa população

doméstica, laboral ou empregadora, diferentemente como ocorre em grande

parte dos países desenvolvidos.

Palavras-chave: Queimaduras; Queimaduras por corrente elétrica; Unidades de queimados; Epidemiologia; Brasil

INTRODUCTION

The use of electric current is essential for different daily activities and can, on certain occasions, cause burns that, in addition to physical problems, are potentially fatal. They are also responsible for causing psychological and social damage1 and, for this reason, are considered a public health problem worldwide2.

Injury caused by the passage of electrical current is defined as tissue damage caused by exposure to supraphysiological electrical current. Electrical burns are classified as high voltage (≥1000 V), low voltage (<1000 V), “flash burn” (in which there is no flow of electrical current through the body of the patient), and burns caused by lightning3.

In Brazil, data published in 2016 by the Brazilian Burn Society showed that approximately one million burns occur annually, and of the patients treated in its burn units (BU), 4 - 8% are due to electrical causes4-6. Thus, this type of burn causes approximately 1,300 deaths/year7; however, in the same period, the United States has approximately 1,000 victims/year8.

Statistics show that the prevalence is higher among men, commonly in the young population, more frequently related to work1,8,9 and is the fourth leading cause of death related to traumatic work10.

Developed countries have made considerable progress in reducing burn death rates through a combination of accident prevention strategies and improvements in assistance to burn victims. However, most strategies have also been applied in underdeveloped countries, without much success, where 95% of burns occur, according to global statistics11.

OBJECTIVE

Epidemiological analysis of patients treated for electrical burns at the BU of the Hospital de Clínicas of the Federal University of Uberlândia (HC-UFU).

METHOD

Cross-sectional study of data recorded in electronic and physical records of patients treated for electrical burns between July 2013 and June 2019 at BU. Patients treated or admitted to other services due to electrical burns were excluded.

The Research Ethics Committee (CEP) approved the research involving human beings at the Federal University of Uberlândia (Opinion No. 4,351,155).

The following variables were considered: incidence, age group, race, sex, city and environment, type of electrical current, anatomical site, extent and degree of burn, types of surgeries, length of hospital stay, and stay in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), intentionality of injury and death.

The data were processed using frequency distribution, and percentages, and expressed in tables, with analysis carried out using the SPSS version 26.0 program.

RESULTS

Distribution by age group, incidence, sex, and race

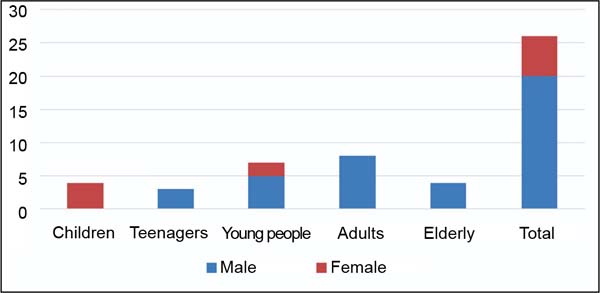

In the HC-UFU Burns Unit, over the six years between July 2013 and June 2019, a total of 309 patients were treated for different types of burns, of which 26 were electrical burns, which corresponds to an incidence of 8.4%, represented in the following distribution: children aged 0 to 10 years 15.3% (n=4); teenagers aged 11 to 18, 11.5% (n=3); young people aged 19 to 35 26.9% (n=7); adults aged 36 to 60 years 30.7% (n=8) and older people aged over 60 years 15.3% (n=4).

In the distribution by sex, males were 76.9% (n=20) and females 23.1% (n=6), with a ratio of 3.3:1, respectively.

From the distribution by age groups and sex, 100% of the children were female; among adolescents, 100% were male; of the young people, 71% were male, and 29% were female. Of the adults, 100% were male, and of the elderly, 100% were male (Figure 1).

From the distribution by race, 57.6% were white (n=15), 30.7% were mixed race (n=8), and 11.5% were black (n=3).

City and environment by age group where the burn occurred

The cities where the burns occurred were Uberlândia-MG, with 38.4% (n=10); Araguari-MG, with 23% (n=6); Patrocínio-MG, with 7.7% (n=2); Prata- MG, with 7.7% (n=2); and other municipalities, with 23% (n=6).

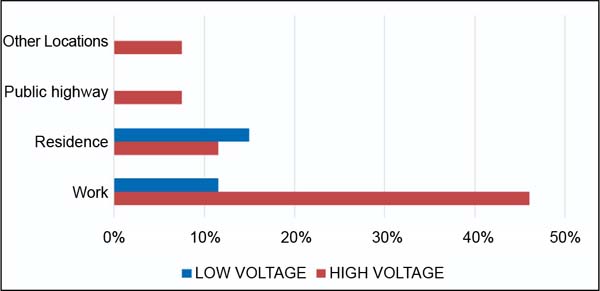

Regarding the environment where the burn occurred, the workplace was 57.7% (n=15), at home 26.9% (n=7), on public roads 7.7% (n=2), and in others 7.7% (n=2). Of workplace traumas, 66.6% were caused by high voltage and 33.4% by low voltage (Figure 2).

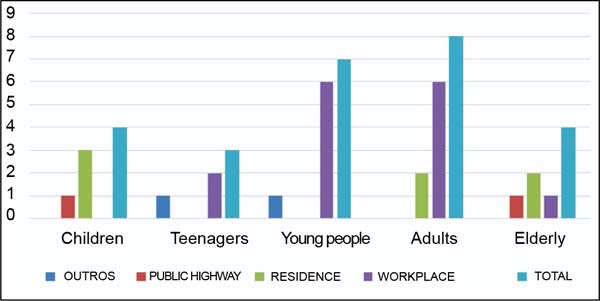

Concerning age group and environment, 75% of burns in children were at home and 25% on public roads; among adolescents, 66.6% were at the workplace and 33.3% at another location; among young people, 85.7% were in the workplace and 14.3% in another location; in adults, 75% occurred in the workplace and 25% at home, with the elderly 50% at home, 25% at the workplace and 25% on public roads. (Figure 3).

Type of electrical voltage of the burn by age category

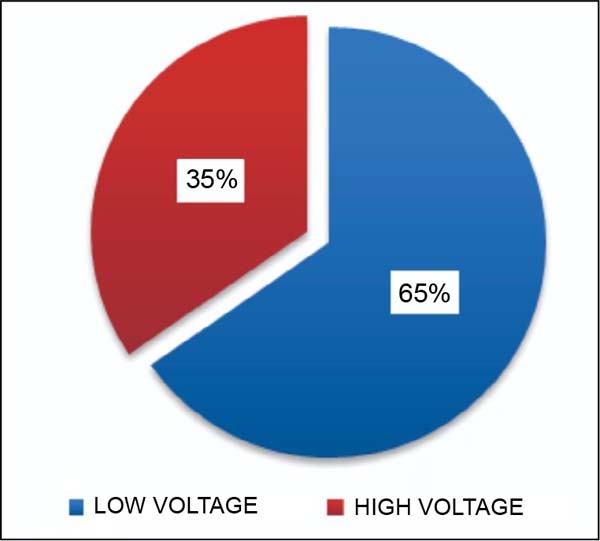

During the study, it was observed that 65.4% of patients were affected by high-voltage currents and 34.6% by low-voltage currents (Figure 4). Men had high-voltage burns in 75% of cases, and women had low-voltage burns in 67%. By age category, children were affected by low-voltage in 75% and high-voltage in 25%. In teenagers, high-voltage burns were 100%. Among young people, high-voltage burns were 71.4%, followed by low voltage 28.6%. In the adult group, high and low-voltage burns were 50% for each type. Among elderly patients, high-voltage burns reached 100%.

Anatomical site of burns

Burns were categorized into 4 distinct anatomical areas. The upper extremities were affected in 80.7%, the lower limbs in 50%, the head, face, and neck in 42.3%, and trunk (including buttocks and genitalia) in 42.3%.

Extent and degree of burns by age category

The extent of burns in children is classified as follows: small (burned body surface - BBS - below 10%), medium (BBS 11-24%), and large (BBS above 25%). In them, 75% of burns were classified as small and 25% as large. For the group of adolescents, young people, and adults, burns were classified as small (BBS below 15%) in 66.6%, 71.4%, and 75%, respectively, as medium (BBS 16-29%) 33, 3%, 28.6% and 25% respectively, but no data on major burns were recorded. Using the same extent categorization for the elderly, 25% were classified as small, 25% as medium, and 50% as large burns (BBS above 30%). The average BBS was 14.5%.

All age groups were classified as second and third-degree burns.

Types of surgeries

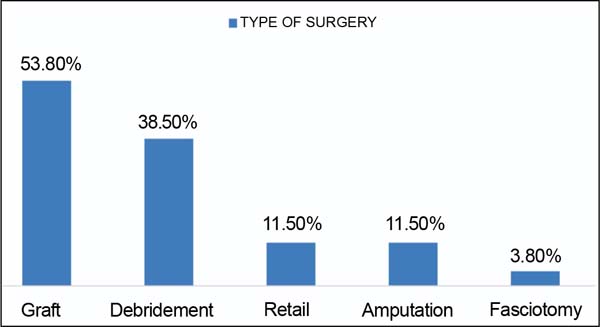

A total of 38.5% (n=10) of patients required surgical debridement, of which 70% (n=7) were affected by high voltage current and 30% (n=3) by low voltage current. Skin autograft surgery was performed in different anatomical areas in 53.8% (n=14), flaps in 11.5% (n=3), amputations of segments of the upper limb in 7.7% (n=2), fasciotomy in 3.8% (n=1) and penile amputation in 3.8% (n=1) (Figure 5).

Hospital stays, and injuries caused intentionally and unintentionally

The average hospital stay in our Burns Unit was 40 days, and only one patient remained in the ICU for 9 days.

Unintentional injuries were 96.2% (n=25) and intentional injuries 3.8% (n=1), with 3.8% (n=1) due to attempted self-extermination.

During this period of six years of hospitalization, 26.9% of patients presented infectious processes, and no deaths were recorded.

DISCUSSION

This type of uncommon trauma has a variable incidence in the different states of Brazil, with our result (8.4%) being higher than that of developed countries (4-6%)8,12, despite this research being carried out in a region with great progress in recent years (HDI 89.9). Uberlândia had the highest number of cases (38.4%), but it is the most populous, developed, and headquarters of the HC-UFU BU. It was followed by Araguari (23%), a city close to HC-UFU.

Of the population groups, the most affected in our region were adults, male and work-related, with a greater incidence among adolescents (66.6%), unlike the statistics observed in other studies6,12,13. This fact is probably related to the greater participation of this group in the job market14. According to labor legislation (articles 402 to 441 of the CTL), minors under the age of 18 are prohibited from working in dangerous or unhealthy conditions.

Among children, domestic injuries were among the most common, in which parents or responsible caregivers could not always keep children under supervision. Contrary to what was seen in the literature, the victims in this study were mostly female15.

The average BBS found among all patients was similar to other studies (14.5%)9; however, as also observed in other studies, we did not find a defined correlation between the external area of electrical burn and the degree of depth of the lesions. The population group with the largest burn areas was the elderly, and this was due to their greater physical and intellectual vulnerability16.

Of the anatomical sites affected, the upper limbs were those that resulted as the most common point of origin of the trauma, as reported in other studies9, followed by the lower limbs17, which during its evolution was the burned area that most required surgical treatment, according to another publication whose research took place at the same BU as HC-UFU18. Debridement followed by skin autograft were the most commonly performed surgical procedures19.

Most patients, except children, suffered burns caused by high voltage current, predominantly males (75%) at their workplace (80%), similar to the results of research carried out in other BUs where victims with more severe burns20,21.

Described as the most destructive burn trauma22, the average length of hospital stay (n=40) was higher than other types of non-electrical burns18, with a predominance of unintentional injuries and an isolated case of attempted self-extermination.

According to data collected from the Mortality Information System in the Information Technology Department of the Unified Health System, from 2000 to 2016, a male mortality of 12.9 and female mortality of 1.7 per 1 million men and women23 were recorded due to electrical causes, however in no deaths were documented in the BU of the HC-UFU, and it may have happened that the most serious cases that arrived at the emergency department of the HC-UFU were sent directly to the ICU, where they could have died without being admitted to our service, or because a large proportion of Deaths from this type of trauma would occur at the scene of the accident, not reaching emergency services7 or were simply classified by another related cause of occupational death, as reported at the Third National Meeting on Safety and Health in the Electrical Sector24.

CONCLUSION

There is a low incidence of patients reporting electrical burns treated at the HC-UFU BU, but the cases were in all age groups, predominantly in the adult male population and in their workplace. All children were female. Debridement surgery with skin autograft was the most commonly performed surgical treatment.

Health promotion, prevention, and protection policies regarding the dangers of electrical currents would not be practiced and disseminated among our domestic, working, or employing population, unlike in most developed countries.

REFERENCES

1. Wesner ML, Hickie J. Long-term sequelae of electrical injury. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(9):935-9.

2. World Health Organization (WHO). [Internet]. Burns. Geneva: WHO; 2018 [acesso 2022 Mar 6]. Disponível em: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns

3. Arnoldo BD, Purdue GF. The diagnosis and management of electrical injuries. Hand Clin. 2009;25(4):469-79.

4. Friedstat J, Brown DA, Levi B. Chemical, Electrical, and Radiation Injuries. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44(3):657-69.

5. Torquato ACS, Leitão PCA, Lima LHG, Lima LG, Ferraz MM, Ferraz MM, et al. Estudo epidemiológico de pacientes com queimaduras por eletricidade atendidos em unidade de queimados em Recife - PE. Rev Fac Cienc Med (Sorocaba). 2015;17(3):120-2.

6. Carvalho CM, Faria GEL, Milcheski DA, Gomez DS, Ferreira MC. Estudo clínico epidemiológico de vítimas de queimaduras elétricas nos últimos 10 anos. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2012;11(4):230-3.

7. Kuiava EL, Kuiava VA, Chielle EO. Análise epidemiológica de lesões fatais causadas por choque elétrico no Brasil. Braz J Health Rev. 2020;3(3):5795-810.

8. Gentges J, Schieche C, Nusbaum J, Gupta N. Points & Pearls: Electrical injuries in the emergency department: an evidence-based review. Emerg Med Pract. 2018;20(Suppl 11):1-2.

9. Gandhi G, Parashar A, Sharma RK. Epidemiology of electrical burns and its impact on quality of life - the developing world scenario. World J Crit Care Med. 2022;11(1):58-69.

10. Koumbourlis AC. Electrical injuries. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(11 Suppl):S424-30.

11. World Health Organization (WHO). A WHO plan for burn prevention and care. Geneva: WHO; 2008 [acesso 2022 Mar 6]. Disponível em: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/97852

12. Brandão C, Vaz M, Brito IM, Ferreira B, Meireles R, Ramos S, et al. Electrical burns: a retrospective analysis over a 10-year period. Ann Burns Fire Disasters. 2017;30(4):268-71.

13. Shih JG, Shahrokhi S, Jeschke MG. Review of Adult Electrical Burn Injury Outcomes Worldwide: An Analysis of Low-Voltage vs High-Voltage Electrical Injury. J Burn Care Res. 2017;38(1):e293-8.

14. Helal DH. Crianças e adolescentes no mercado de trabalho brasileiro: padrões e tendências. Pesqui Prát Psicossociais. 2010;5(1):83-93.

15. Takino MA, Valenciano PJ, Itakussu EY, Kakitsuka EE, Hoshimo AA, Trelha CS, et al. Perfil epidemiológico de crianças e adolescentes vítimas de queimaduras admitidos em centro de tratamento de queimados. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2016;15(2):74-9.

16. Brasil. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). Pesquisa Nacional de Saúde 2013: Ciclos de Vida. Rio de Janeiro: IBGE; 2015. [acesso 2022 Out 25]. Disponível em: https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/livros/liv94522.pdf

17. Jiang MJ, Li Z, Xie WG. Epidemiological investigation on 2133 hospitalized patients with electrical burns. Zhonghua Shao Shang Za Zhi. 2017;33(12):732-7.

18. Mego IOG, Cruvinel SS, Duarte AR, Teles-de-Oliveira-Junior GA, Carneiro RMS. Unidade de queimados do Hospital de Clínicas da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Brasil: estudo epidemiológico. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2022;37(2):189-93.

19. Tondineli TH, Rios JAS, Candelario K, Ribeiro RC, Maceira Junior L, Freitas MCV. Queimaduras elétricas por alta voltagem: cinco anos de análise epidemiológica e tratamento cirúrgico atualizado. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2016;31(3):380-4.

20. Salehi SH, Sadat Azad Y, Bagheri T, Ghadimi T, Rahbar A, Ehyaei P, et al. Epidemiology of Occupational Electrical Injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2022;43(2):399-402.

21. Souza AL, Oliveira BC, Andrade C, Monteso K, Rebelo PG, Rodrigues RPC. Queimadura elétrica no Hospital Federal do Andaraí de 1997 a 2010: análise de 152 casos. Rev Bras Queimaduras. 2012;11(2):80-4.

22. Bounds EJ, Khan M, Kok SJ. Electrical Burns. StatPearls. Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2022. [acesso 2022 Abr 28]. Disponível em: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519514/

23. Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. DATASUS. Dados estatísticos de mortes por trauma causado por queimadura elétrica. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde; 2019 [acesso 2019 Jul 22]. Disponível em: http://www.datasus.gov.br/cid10/V2008/WebHelp/w85_w99.htm

24. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Riscos dos Choques Elétricos [Internet]. [acesso 2019 Jul 22]. Disponível em: http://www.ufrrj.br/institutos/it/de/acidentes/eletric.htm

1. Hospital das clínicas, Universidade Federal de

Uberlândia, Uberlândia, MG, Brazil

2. Hospital Geral Vila Penteado, São Paulo, SP,

Brazil

Corresponding author: Iván Orlando Gonzales Mego Av. Pará, 1720, Umuarama, Uberlândia, MG, Brazil, Zip Code: 38405-320, E-mail: medicogonzales@hotmail.com

Article received: May 19, 2022.

Article accepted: June 13, 2023.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter