Original Article - Year 2023 - Volume 38 -

Profile of oncological and breast repair surgeries in northern Brazil: Analysis of the last decade

Perfil das cirurgias oncológicas e reparadoras de mama no norte do Brasil: Análise da última década

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Late breast cancer diagnosis increases the number of surgeries, resulting in high mortality and unsightly results. Therefore, the institution of breast reconstruction procedures is essential.

Method: Descriptive, quantitative, and retrospective study on authorizations for hospital admission of patients undergoing breast surgical procedures in oncology from 2011 to 2020, whose data were obtained from the DATASUS platform.

Results: 7,529 breast cancer surgeries and 1,949 reconstructive surgeries were performed in the North Region. There was an increase in the number of procedures throughout the decade. In all states, it is possible to notice the difference in the number of municipalities of residence compared to the municipalities of hospitalization.

Conclusion: It is necessary to establish oncological reference centers, guaranteeing individualized treatment and breast reconstruction.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms; Mastectomy; Reconstructive surgical procedures; Mammaplasty; Epidemiology.

RESUMO

Introdução: O diagnóstico tardio do câncer de mama eleva o número de cirurgias,

resultando em alta mortalidade e resultado pouco estético. Assim, é

fundamental a instituição de procedimentos de reconstrução mamária.

Método: Estudo descritivo, quantitativo e retrospectivo sobre as autorizações de

internação hospitalar de pacientes submetidos a procedimentos cirúrgicos de

mama em oncologia, no período de 2011 a 2020, cujo dados foram obtidos na

plataforma DATASUS.

Resultados: 7.529 cirurgias de câncer de mama e 1.949 cirurgias reparadoras foram

realizadas na Região Norte. Houve aumento do número de procedimentos ao

longo da década. Em todos os estados é possível perceber a diferença no

número de municípios de residência, comparado aos municípios de

internação.

Conclusão: Necessita-se instituir centros de referência oncológica, garantindo

tratamento individualizado e a reconstrução mamária.

Palavras-chave: Neoplasias da mama; Mastectomia; Procedimentos cirúrgicos reconstrutivos; Mamoplastia; Epidemiologia.

INTRODUCTION

Considering its worldwide distribution, breast cancer is the most common cancer among women1. In Brazil, excluding non-melanoma skin tumors, this cancer ranks first in all regions, resulting in an estimated risk of 61.61 new cases for every 100 thousand women1. In a Brazilian historical series, mortality rates from this malignancy show an upward trend, with the North Region showing accelerated growth rates, which constitutes a public health problem2.

Breast cancer treatment is based on clinical and surgical3,4. The latter is subdivided into a conservative approach, reserved for cases of early diagnosis, and a radical technique, invasive surgery, for more advanced cases3-6. Despite the various therapeutic possibilities, high mortality results from the low opportunity for access to screening, which results in late detection, radical treatment, and a poor prognosis3-5.

It is observed that late diagnosis increases the number of surgeries, especially mutilating surgeries, such as radical mastectomies, which have chronic pain and swelling as sequelae, with high mortality and unaesthetic results that affect the quality of life3-7. Psychological disorders, changes in self-image and self-esteem, a sense of loss of femininity, and emotional and social changes are common and affect family and work life, in addition to implying greater expenses with treatments3-8.

Therefore, it is essential to refine surgical techniques and implement breast reconstruction procedures, combining principles of oncological surgery and plastic surgery4-6. Breast implants, tissue expansion techniques, and myocutaneous flaps are examples of reconstructive surgeries4-7. In this context, the Breast Reconstruction Law (Law No. 12,802/2013)9 guaranteed the right to perform the procedure for mastectomized patients, aiming to minimize the physical and emotional impact and improve quality of life5-7.

Despite the guaranteed right, few women treated surgically for cancer have access to breast reconstruction, one of the main factors being the small number of structured public reference services, as well as the small number of surgeons specializing in oncoplasty in the public health system5, 6,8,10,11.

In this context, despite the clinical-epidemiological relevance of this topic for women’s health, no current research was found in the literature on the distribution of these surgeries in the North Region.

OBJECTIVE

To analyze the profile of breast cancer surgeries and breast reconstruction surgeries performed in the Northern Region of Brazil, in the public health network, from 2011 to 2020.

METHOD

Descriptive, quantitative and retrospective study whose data were obtained from the databases of the Hospital Information System of the Unified Health System (SIH/SUS), available at the Information Technology Department of the Unified Health System (DATASUS), at the electronic address https://datasus.saude.gov.br/acesso-a-informacao/producao-hospitalar-sih-sus/, with access date on 11/11/2021.

All approved hospital admission authorizations (AIH) of patients undergoing breast surgical procedures in oncology in the North Region were analyzed from 2011 to 2020.

The procedures under analysis were subdivided into two groups:

Breast cancer surgeries (code 0416120032 - simple mastectomy in oncology; 0416120024 - radical mastectomy with axillary lymphadenectomy in oncology; code 0416120059 - breast segmentectomy/quadrantectomy/ sectorectomy in oncology; code 0416020216 - unilateral axillary lymphadenectomy in oncology; code 0416020062 - unilateral radical axillary lymphadenectomy in oncology; code 0416020054 - bilateral radical axillary lymphadenectomy in oncology; code 0416120040 - resection of non-palpable breast lesion with marking in oncology) and

Breast plastic surgery (code 0410010090 - post-mastectomy reconstructive breast plastic with prosthesis implant; code 0410010073 - non-aesthetic female breast plastic surgery). The surgical procedure codes are described in Table 1.

| Surgical

procedure codes |

Surgical procedure codes |

|---|---|

| 0416120032/0416120024 | Mastectomies in oncology |

| 0416120059 | Segmentectomy/quadrantectomy/ breast sectorectomy in oncology |

| 0416020216/ 0416020062/ 0416020054 | Axillary lymphadenectomies in oncology |

| 0416120040 | Resection of non-palpable breast lesion in oncology |

| 0410010090/ 0410010073 | Breast plastic surgery |

Source: data extracted from DATASUS.

The data were tabulated and categorized according to the municipality, federative unit, region, and year of service. The incidence coefficient was distributed by equal frequencies and calculated by dividing the absolute number of procedures in each municipality by the respective resident population and multiplied by 100,000. The number of the resident population was collected from the Population Estimates Study, available on the DATASUS online platform. In order to illustrate the data, the TabWin v4.15 program, available on DATASUS, was used to create maps referring to the North Region.

This research was based on information contained in a public domain secondary database, with no need to submit it to the Research Ethics Committee.

RESULTS

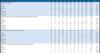

In the period from 2011 to 2020, 7529 breast cancer surgeries were performed in the North Region. Of this total, radical treatment, simple and radical mastectomies, was the most frequent surgical procedure, corresponding to 61.1% of total surgeries, followed by conservative treatment, including segmentectomy/quadrantectomy/sectorectomy, corresponding to 23% of surgeries. Resection of non-palpable breast lesions in oncology accounted for 11.5% of surgical cases, and axillary lymphadenectomies totaled 4.23% (Table 2).

| Procedures/Federative Unit | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | TOTAL | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MASTECTOMIES | 375 | 324 | 399 | 391 | 385 | 489 | 559 | 563 | 571 | 549 | 4605 | |

| Acre | 23 | 9 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 16 | 18 | 12 | 15 | 24 | 147 | 3% |

| Amapá | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 10 | 12 | 17 | 16 | 67 | 1% |

| Amazon | 137 | 129 | 137 | 93 | 72 | 133 | 175 | 157 | 191 | 170 | 1394 | 30% |

| Pará | 165 | 134 | 172 | 200 | 184 | 202 | 227 | 221 | 179 | 174 | 1858 | 40% |

| Rondônia | 8 | 0 | 26 | 44 | 62 | 66 | 74 | 79 | 82 | 91 | 532 | 12% |

| Roraima | 12 | 16 | 9 | 15 | 21 | 18 | 15 | 23 | 23 | 25 | 177 | 4% |

| Tocantins | 28 | 30 | 43 | 31 | 35 | 51 | 40 | 59 | 64 | 49 | 430 | 9% |

| SEGMENTECTOMY/QUADRANTECTOMY/SETORECTOMY | 26 | 16 | 96 | 124 | 137 | 233 | 236 | 255 | 339 | 277 | 1739 | |

| Acre | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 39 | 2% |

| Amapá | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 16 | 41 | 2% |

| Amazon | 6 | 0 | 13 | 13 | 32 | 81 | 86 | 81 | 130 | 125 | 567 | 33% |

| Pará | 0 | 0 | 29 | 51 | 44 | 92 | 76 | 87 | 120 | 65 | 564 | 32% |

| Rondônia | 1 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 14 | 18 | 25 | 24 | 17 | 9 | 121 | 7% |

| Roraima | 6 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 72 | 4% |

| Tocantins | 10 | 6 | 33 | 43 | 37 | 28 | 26 | 43 | 56 | 53 | 335 | 19% |

| RECONSTRUCTIVE BREAST PLASTIC | 136 | 132 | 166 | 222 | 170 | 151 | 234 | 294 | 310 | 134 | 1949 | |

| Acre | 19 | 5 | 14 | 18 | 17 | 15 | 21 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 124 | 6% |

| Amapá | 16 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 15 | 16 | 25 | 18 | 23 | 4 | 174 | 9% |

| Amazon | 22 | 43 | 54 | 95 | 54 | 54 | 41 | 50 | 50 | 28 | 491 | 25% |

| Pará | 30 | 29 | 28 | 41 | 56 | 44 | 51 | 134 | 126 | 76 | 615 | 32% |

| Rondônia | 35 | 15 | 11 | 6 | 17 | 14 | 48 | 65 | 75 | 16 | 302 | 15% |

| Roraima | 3 | 13 | 21 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 16 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 79 | 4% |

| Tocantins | 11 | 8 | 20 | 34 | 10 | 5 | 32 | 12 | 27 | 5 | 164 | 8% |

| AXILLARY LYMPHADENECTOMIES IN ONCOLOGY | 15 | 28 | 20 | 20 | 29 | 51 | 54 | 29 | 40 | 33 | 319 | |

| Acre | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 2% |

| Amapá | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 6 | 2% |

| Amazon | 7 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 11 | 68 | 21% |

| Pará | 2 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 17 | 15 | 11 | 14 | 2 | 83 | 26% |

| Rondônia | 0 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 13 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 13 | 67 | 21% |

| Roraima | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 30 | 9% |

| Tocantins | 4 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 59 | 18% |

| RESECTION OF NON-PALPABLE BREAST LESION | 63 | 56 | 71 | 48 | 37 | 66 | 62 | 102 | 174 | 187 | 866 | |

| Acre | 0 | 3 | 27 | 12 | 8 | 11 | 22 | 51 | 38 | 39 | 211 | 24,4% |

| Amapá | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0,3% |

| Amazon | 46 | 33 | 28 | 16 | 14 | 17 | 14 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 186 | 21,5% |

| Pará | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 1,8% |

| Rondônia | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 36 | 19 | 37 | 124 | 139 | 369 | 42,6% |

| Roraima | 0 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 1,0% |

| Tocantins | 16 | 15 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 72 | 8,3% |

| GRAND TOTAL | 615 | 556 | 752 | 805 | 758 | 990 | 1145 | 1243 | 1434 | 1180 | 9478 |

Source: data extracted from DATASUS.

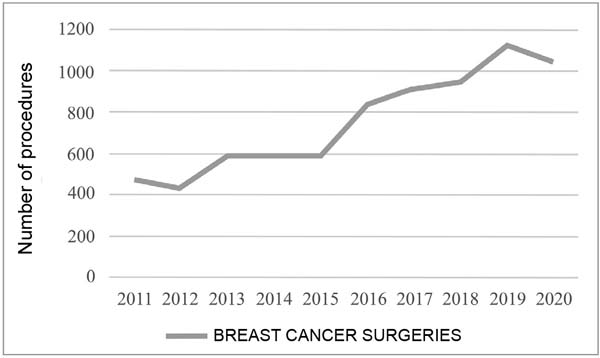

Regarding the year in which breast surgeries were performed, an increase in the number of procedures was noted throughout the decade. 2020 showed a slight reduction in surgeries compared to the previous year (Figure 1).

When it comes to mortality due to the surgical procedure, bringing together all the surgery codes mentioned, 22 deaths were recorded, 68.1% of which were notifications in the state of Pará, followed by Amazonas (22.7%), Tocantins and Rondônia, both with 4 .5% of deaths. Acre, Amapá, and Roraima states did not report deaths from breast cancer surgeries in the period analyzed.

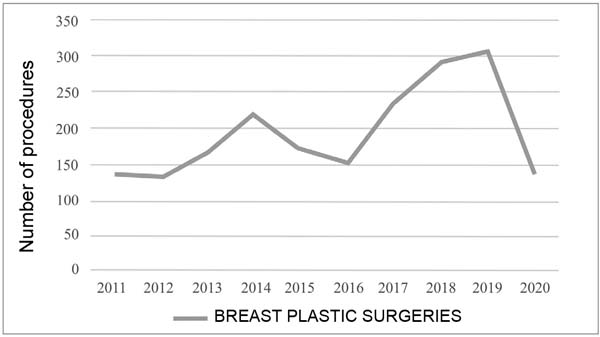

There were a total of 1949 procedures in the North Region for reconstructive breast plastic surgeries. The state that most reported this procedure was Pará (31%), followed by Amazonas (25%), Rondônia (15%), Amapá (8%), Tocantins (8%), Acre (6%) and Roraima (4 %) (Table 2).

Regarding the year this procedure was carried out, the years 2018 and 2019 were those with the highest number of notifications. Conversely, 2011, 2012, and 2020 showed a drop in the total number of reports of reconstructive surgeries (Figure 2).

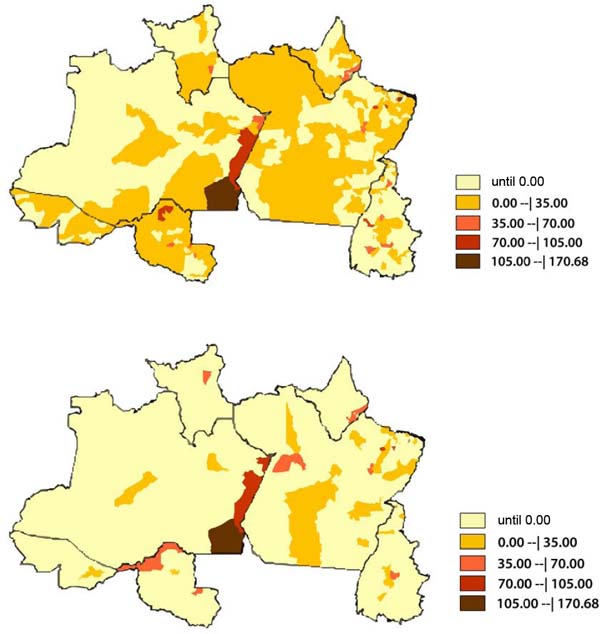

The map described compares the incidence rate of breast plastic surgeries by place of residence and by place of hospitalization for each federative unit in the Northern Region. Of 450 municipalities in the country’s north, 191 municipalities correspond to notification by residence, and only 40 report hospitalizations for reconstructive plastic surgery.

In all states, it is possible to notice the difference in the number of municipalities of residence compared to the number of municipalities of hospitalization. For example, it is clear that, in the state of Amazonas, 21 municipalities reported as places of residence, but only 5 municipalities as places of hospitalization. The same happened in the state of Rondônia, contrasting 38 municipalities of residence and 4 municipalities of hospitalization. The state of Pará, numerically more expressive, contrasts 74 municipalities of residence against 21 of hospitalization (Figure 3).

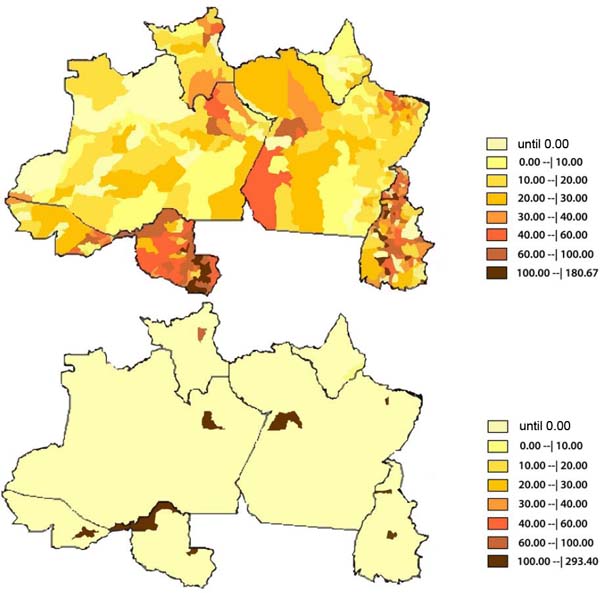

Likewise, the map below compares the incidence coefficient of breast surgeries in oncology by place of residence and by place of hospitalization for each federative unit. A greater number of municipalities are notified regarding place of residence, compared to the small number of municipalities notified by place of hospitalization for each state. For example, in Pará, 134 municipalities were notified as the place of residence, compared to 2 municipalities notified as the place of hospitalization. In the state of Rondônia, 51 municipalities of residence were notified against 2 municipalities of hospitalization; the same happened in the state of Amazonas, contrasting 49 municipalities of residence compared only to the municipality of Manaus, the only place of hospitalization notified (Figure 4).

DISCUSSION

Between 2011 and 2020, 61.1% of surgeries corresponded to radical approaches and only 23% to conservative approaches. This same proportion was found in a reference hospital in Paraíba study, in which 68.8% of patients underwent radical surgical treatment13. Regarding the national scenario, a survey found that of the total number of breast cancer surgeries performed in the country between 2015 and 2020, 43% corresponded to some type of mastectomy12.

This large percentage of radical treatment is justified by the significant proportion of breast cancer cases classified as advanced disease - stages II and III - before the start of treatment, this being even more significant in the North Region when compared to the rest of the country ( 50.1%)12-14. As a result, the difficulty in accessing public health services, the lack of information about the importance of self-care, and the geographical distance from reference centers increase the time between suspicion and diagnostic confirmation, worsen the clinical picture, and support more invasive therapeutic measures, unfavorable aesthetic results and worse prognosis2,12-14.

The need to carry out radical treatment for a patient with breast cancer implies greater risks and morbidity2,12,14. A series of studies have proven the large window of time that exists in post-treatment with a radical approach and the body acceptance process4-8. Many mastectomized women, sometimes associated with difficulties in accessing multidisciplinary treatment, develop chronic post-traumatic stress and psycho-emotional and psychosocial disorders, especially related to the body and social expectations of femininity, which impact the course and adherence to adjuvant treatment4-8,15. Due to this, the need to invest in screening and early diagnosis, aiming at conservative treatment, as well as guaranteeing access to the multidisciplinary team to improve quality of life during treatment is understood.

During the period analyzed, a growth rate of 1500% in breast surgeries was noted, justified by the increasing incidence of this type of cancer in the country1. The estimate is 66,280 new cases for each year of the 2020-2022 period1. There was a reduction in elective surgeries in 2020, resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, which had a negative impact on medical services around the world16-18. There was a greater impact on reconstructive surgeries, which, in the face of a pandemic scenario, are not considered a priority and can be performed late.

Regarding mortality due to surgical procedures, the low number of absolute deaths associated with surgery is evident. Although the surgical procedure is responsible for low mortality resulting from the surgical procedure directly, breast cancer, when untreated or diagnosed in advanced stages, is responsible for the first cause of death in the Brazilian female population, with an increasing trend over the last decades1,14, with an estimated death risk of 16.16 per 100 thousand women, which scales its magnitude as a public health problem1,2,12,14.

With advancements in medicine and understanding global health care, reconstructive surgeries have gained great visibility19. In Brazil, Federal Law No. 12.8029 recognized the obligation to offer breast reconstructive surgeries for mastectomized patients and must be offered by all SUS institutions3,5,9.

Despite this great achievement, its applicability is still lacking, insufficient to match the number of mastectomies performed with breast reconstruction3,20,21.

This is justified by the low number of reconstructive surgeries found in the study compared to the number of oncological surgeries. In a study of the Brazilian panorama of breast surgeries, a similar result was found, in which only 20% of Brazilian women had the guaranteed right to plastic surgery with post-mastectomy breast implants, with the North Region having the lowest number of reconstructive surgeries (1.79%)12.

The 2017-2019 triennium was responsible for the highest number of surgeries, which can be justified by the guarantee of the Breast Reconstruction Law, starting in 20139. Otherwise, the years 2011, 2012, and 2020 marked a lower number of surgeries. Changes in hospital management, reduction of surgeons specialized in oncoplasty, and reduction in funds allocated to this area in the public health system are possible causes of this decrease. Another factor associated with the year 2020 is the pandemic that further reduced the access of mastectomized patients to the right to reconstructive surgery due to the restriction of beds for elective surgeries17,18. It is also worth highlighting that the infrastructure and health service model and the degree of impact of the pandemic predict how each country can overcome delays and the increase in the queue of patients requiring late reconstructions12,17-19.

Another point analyzed in the study concerns the contrast between the number of municipalities per residence and the small number of municipalities per breast surgery hospitalization. This difference is justified, among other factors, by the reduced number of reference services in cancer treatment and the consequent lack of infrastructure to increase the demand for care3,11,20-23.

The disparity is even more significant when analyzing plastic breast reconstruction surgeries, where the number of municipalities of hospitalization is more restricted in the states of the Northern Region - only 9% of municipalities have notifications of reconstructive surgery. This discrepancy is related to the lack of reference services with adequate infrastructure and logistics, which, consequently, overcrowded the queue and increased the delay in guaranteeing access to the right to reconstructive surgery11,20-22.

Another factor refers to the low number of trained surgeons with the capacity to perform oncoplasty, considering the country’s demand and the reduced salaries in public services compared to private ones, which reduces the permanence of these professionals in this sector11,12,20-24. According to the Medical Demography of Brazil, from 2020, there are 6152 plastic surgeons and 2302 active mastologists25.

Furthermore, these specialist surgeons are heterogeneously distributed between regions, mainly in the South-Southeast axis, aggravated by geographic disparities3,11,19-23. Given these conditions, the flow of patients is limited to a restricted number of municipalities responsible for receiving a large demand for cancer patients11,19-23.

The territorial magnitude of Brazil and its diversity in epidemiological profile translate into differences in accessibility to healthcare22,24. The great contrast between the notification by municipalities that exists between the states of the Northern Region allows us to identify barriers in the availability and accessibility of patients diagnosed with breast cancer in reference services and, therefore, the need to expand infrastructure and health care for this population group.

The main limitation of the present work is the possibility of underreporting, in which a smaller number of the procedures mentioned have been analyzed when compared to the numerical reality of reference centers. Another limitation is the possible erroneous classifications related to the choice of procedure codes in DATASUS, both by professionals when filling out the AIHs and by the departments responsible for notifying the platform. Furthermore, it should be noted that the database does not differentiate by different codes the different types of reconstruction using myocutaneous flaps that exist in oncology, grouping them all into a single code, therefore limiting their use in the present research.

CONCLUSION

The growing number of breast cancer surgeries in the North corresponds, for the most part, to radical approaches, in contrast to the still low number of breast reconstruction surgeries. Finally, the existing heterogeneity between notification municipalities in the North of the country was demonstrated, which reveals the need to reorganize and establish new oncology reference centers to guarantee access to individualized and early diagnosis and treatment, increasing chances of conservative treatment and guaranteeing the right to reconstruction after radical treatment.

REFERENCES

1. Brasil. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Estimativa 2020: incidência de câncer no Brasil. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2019.

2. Brasil. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). Atlas da mortalidade. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2021.

3. Freitas-Júnior R, Gagliato DM, Moura Filho JWC, Gouveia PA, Rahal RMS, Paulinelli RR, et al. Trends in breast cancer surgery at Brazil’s public health system. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115(5):544-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.24572

4. Pereira APVM, Santos GRF, Furtado LFT, Molina MA, Luz TFN, Esteves APVS. Mastectomia e mamoplastia na vida das mulheres com câncer de mama. Rev Cad Med. 2019;2(1):38-52.

5. Leite EPLA, Silva JR, Moura SEB, Paiva CB, Ferreira TTC. Impacto da reconstrução mamária na qualidade de vida de mulheres mastectomizadas. Rev Eletr Acervo Saúde. 2019;35(Supp 35):e1502. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25248/reas.e1502.2019

6. Volkmer C, Santos EKA, Erdmann AL, Sperandio FF, Backes MTS, Honório GJS. Reconstrução mamária sob a ótica de mulheres submetidas à mastectomia: uma metaetnografia. Texto Contexto Enferm. 2019;28:e20160442. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-265X-TCE-2016-0442

7. Oliveira RR, Morais SS, Sarian LO. Efeitos da reconstrução mamária imediata sobre a qualidade de vida de mulheres mastectomizadas. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2010;32(12):602-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S0100-72032010001200007

8. Brandão BL, Silva ACB, Francisquini IN, Gouvêa MM, Lobão LM. Importance of plastic surgery for women with mastectomies and the role of Brazilian Unified Health System: integrative review. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2021;36(4):457-65. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5935/2177-1235.2021RBCP0132

9. Brasil. Lei Nº 12.802, de 24 de abril de 2013. Altera a Lei nº 9.797, de 6 de maio de 1999, que “dispõe sobre a obrigatoriedade da cirurgia plástica reparadora da mama pela rede de unidades integrantes do Sistema Único de Saúde nos casos de mutilação decorrentes de tratamento de câncer”, para dispor sobre o momento da reconstrução mamária. Brasília: Diário Oficial da União; 2013.

10. Albornoz CR, Bach PB, Mehrara BJ, Disa JJ, Pusic AL, McCarthy CM, et al A paradigm shift in U.S. Breast reconstruction: increasing implant rates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131(1):15-23. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182729cde

11. Jagsi R, Jiang J, Momoh AO, Alderman A, Giordano SH, Buchholz TA, et al. Trends and variation in use of breast reconstruction in patients with breast cancer undergoing mastectomy in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(9):919-26. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.52.2284

12. Almeida CSC, Morais RXB, França IR, Cavalcante KWM, Santos ALBN, Morais BXB, et al. Análise comparativa das mastectomias e reconstruções de mama realizadas no sistema único de saúde do Brasil nos últimos 5 anos. Rev Bras Cir Plást. 2021:36(3):263-9. DOI: http://www.dx.doi.org/10.5935/2177-1235.2021RBCP0039

13. Cavalcante JAG, Batista LM, Assis TS. Câncer de mama: perfil epidemiológico e clínico em um hospital de referência na Paraíba. Sanare (Sobral, Online). 2021;20(1):17-24.

14. Brasil. Instituto Nacional de Câncer José Alencar Gomes da Silva (INCA). A situação do câncer de mama no Brasil: síntese de dados dos sistemas de informação. Rio de Janeiro: INCA; 2019.

15. Soares PBM, Quirino Filho S, Souza WPD, Gonçalves RCR, Martelli DRB, Silveira MF, et al. Características das mulheres com câncer de mama assistidas em serviços de referência do Norte de Minas Gerais. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2012;15(3):595-604. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-790X2012000300013

16. Izydorczyk B, Kwapniewska A, Lizinczyk S, Sitnik-Warchulska K. Psychological Resilience as a Protective Factor for the Body Image in Post-Mastectomy Women with Breast Cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):1181. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061181

17. Sun P, Luan F, Xu D, Cao R, Cai X. Breast reconstruction during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(33):e26978. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000026978

18. Hemal K, Boyd CJ, Bekisz JM, Salibian AA, Choi M, Karp NS. Breast Reconstruction during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2021;9(9):e3852. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/GOX.0000000000003852

19. Boyce L, Nicolaides M, Hanrahan JG, Sideris M, Pafitanis G. The early response of plastic and reconstructive surgery services to the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2020;73(11):2063-71. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2020.08.088

20. Lang JE, Summers DE, Cui H, Carey JN, Viscusi RK, Hurst CA, et al. Trends in post-mastectomy reconstruction: a SEER database analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108(3):163-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.23365

21. Yang RL, Newman AS, Lin IC, Reinke CE, Karakousis GC, Czerniecki BJ, et al. Trends in immediate breast reconstruction across insurance groups after enactment of breast cancer legislation. Cancer. 2013;119(13):2462-8. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.28050

22. Urban C, Freitas-Junior R, Zucca-Matthes G, Biazús JV, Brenelli FP, Pires DM, et al. Oncoplastic and reconstructive surgery of the breast: Consensus Meeting of the Brazilian Society of Mastology. Rev Bras Mastologia. 2015;25(4):118-24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5327/Z201500040002RBM

23. Alderman AK, Atisha D, Streu R, Salem B, Gay A, Abrahamse P, et al. Patterns and correlates of postmastectomy breast reconstruction by U.S. Plastic surgeons: results from a national survey. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127(5):1796-803. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e31820cf183

24. Liedke PE, Finkelstein DM, Szymonifka J, Barrios CH, Chavarri-Guerra Y, Bines J, et al. Outcomes of breast cancer in Brazil related to health care coverage: a retrospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(1):126-33. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0693

25. Scheffer M, org. Demografia médica no Brasil 2020. São Paulo: FMUSP, CFM; 2020. 312 p.

1. Universidade Federal do Pará, Belém, PA,

Brazil

2. Universidade do Estado do Pará, Belém, PA,

Brazil

3. Hospital Ophir Loyola, Belém, PA,

Brazil

Corresponding author: Nyara Rodrigues Conde de Almeida Avenida Perimetral, 1284, Belém, PA, Brazil, Zip Code: 66079-420, E-mail: nyaraconde@gmail.com

Article received: April 09, 2022.

Article accepted: May 26, 2023.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Read in Portuguese

Read in Portuguese

Read in English

Read in English

PDF PT

PDF PT

Print

Print

Send this article by email

Send this article by email

How to Cite

How to Cite

Mendeley

Mendeley

Pocket

Pocket

Twitter

Twitter